Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment, Renewal, and Cost-Sharing Policies as of January 2016: Findings from a 50-State Survey

Tricia Brooks, Sean Miskell, Samantha Artiga, Elizabeth Cornachione, and Alexandra Gates

Published:

Executive Summary

January 2016 marks the end of the second full year of implementation of the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) key coverage provisions. This 14th annual 50-state survey of Medicaid and CHIP eligibility, enrollment, renewal, and cost-sharing policies provides a point-in-time snapshot of policies as of January 2016 and identifies changes in policies that occurred during 2015. Coverage is driven by two key elements—eligibility levels determine who may qualify for coverage, and enrollment and renewal processes influence the extent to which eligible individuals are enrolled and remain enrolled over time. This report provides a detailed overview of current state policies in these areas, which have undergone significant change as a result of the ACA.

Together, the findings show that, during 2015, states continued to implement the major technological upgrades and streamlined enrollment and renewal processes triggered by the ACA. These changes are helping to connect eligible individuals to Medicaid coverage more quickly and easily and to keep eligible people enrolled as well as contributing to increased administrative efficiencies. However, implementation varies across states, and lingering challenges remain. The findings illustrate that the program continues to be a central source of coverage for low-income children and pregnant women nationwide and show the growth in Medicaid’s role for low-income adults through the ACA Medicaid expansion.

Eligibility for Children, Pregnant Women, and Non-Disabled Adults

Medicaid and CHIP remained the central sources of coverage for low-income children and pregnant women nationwide during 2015. As of January 2016, 48 states cover children with incomes at or above 200% FPL, with 19 states extending eligibility to at least 300% FPL, while 33 states cover pregnant women with incomes at or above 200% FPL. Eligibility levels for children and pregnant women remained stable during 2015. This stability, in part, reflects the ACA’s maintenance of effort provisions, which prevent states from making any reductions in children’s eligibility through 2019. Some states made incremental changes that expanded access to coverage for children and pregnant women in 2015, such as eliminating waiting periods that required children to be uninsured for a period of time before enrolling in CHIP (Michigan and Wisconsin), eliminating the five-year waiting period for lawfully residing immigrant children and pregnant women (Colorado), expanding federally-funded CHIP coverage to dependents of state employees (Nevada and Virginia), and offering coverage to former foster youth from other states (New Mexico).

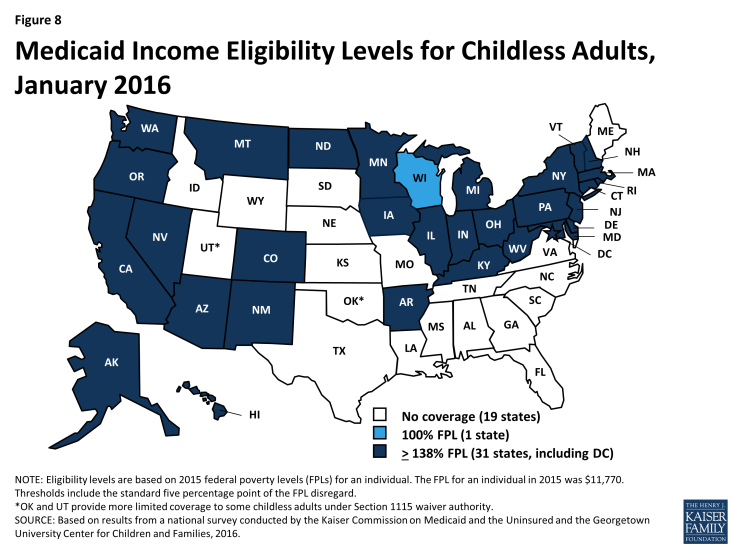

Medicaid’s role for low-income adults continued to grow through the ACA Medicaid expansion. As of January 2016, 31 states have expanded Medicaid eligibility to parents and other non-disabled adults with incomes up to at least 138% FPL. This count reflects the adoption of the Medicaid expansion in three states—Alaska, Indiana, and Montana—during 2015. However, in the 20 states that have not expanded, median eligibility levels are 42% FPL for parents and 0% FPL for other adults, leaving many poor adults in a coverage gap since they earn too much to qualify for Medicaid but not enough for tax credit subsidies to purchase Marketplace coverage, which begin at 100% FPL. Aside from adoption of the Medicaid expansion in three states, there were few changes in eligibility for parents and other adults during 2015. Connecticut reduced eligibility for parents, but eligibility remains above the expansion limit and many of those who became ineligible likely qualify for subsidies to purchase Marketplace coverage. In addition, New York implemented a Basic Health Program (BHP) to offer more affordable coverage to adults with incomes up to 200% FPL, joining Minnesota as the second state with a BHP.

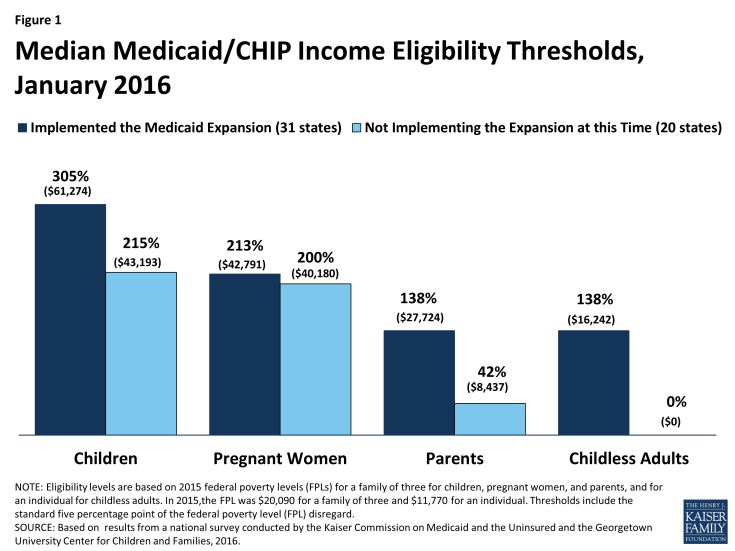

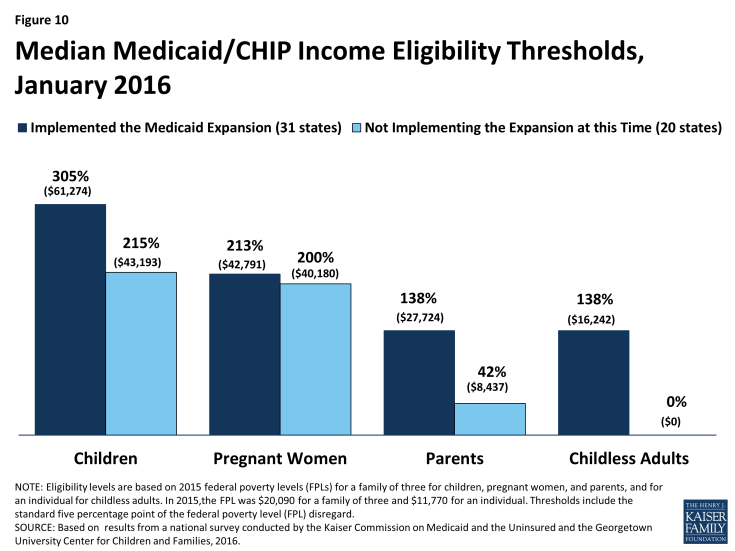

Eligibility levels vary across groups and states, and state Medicaid expansion decisions have increased these differences. Median eligibility levels for children and pregnant women remain well above those for parents and other adults in both Medicaid expansion and non-expansion states. Within each eligibility group, median eligibility levels are higher in expansion states than non-expansion states (Figure 1). As expected, these differences between expansion and non-expansion states are largest for parents and other adults. Underlying these medians, there also is significant variation in eligibility levels across states. Eligibility levels range from 152% to 405% FPL for children, from 138% to 380% FPL for pregnant women, from 18% to 221% FPL for parents, and from 0% to 215% for other adults.

System Enhancements and Streamlined Enrollment and Renewal

Regardless of whether states have implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion to adults, the law ushered in major changes to Medicaid systems and processes in all states. The changes are designed to harness technology to provide a modernized enrollment experience for consumers and may lead to increased administrative efficiencies for states. As documented in last year’s survey, many states faced significant challenges implementing new systems and processes when they were launched in 2014. These difficulties resulted in backlogs and delays in enrollments and renewals, which were a major focus during 2014. This year’s findings show that, in 2015, states resolved many of these challenges and built on successes to refine and enhance their upgraded systems. However, experiences vary across states and lingering challenges remain.

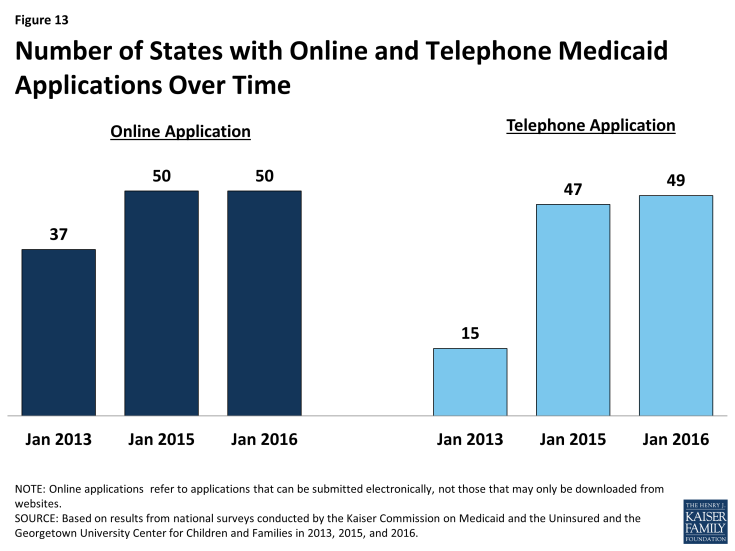

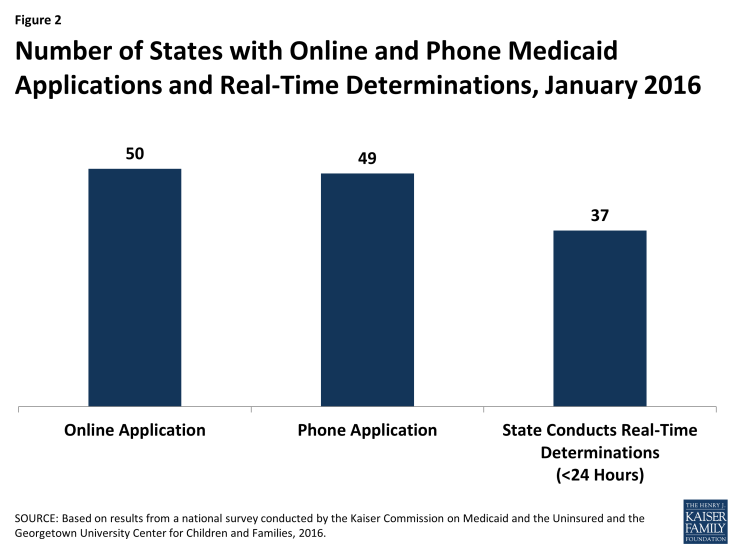

As of January 2016, individuals can apply for Medicaid online or by phone in nearly all states as envisioned by the ACA (Figure 2). All states, except Tennessee, have an online Medicaid application available either through the state Medicaid agency or an integrated portal that provides access to Medicaid and the State-Based Marketplace (SBM). Two states (Arkansas and Florida) began accepting telephone applications for Medicaid in 2015, bringing the total count of states doing so to 49 as of January 2016.

Figure 2: Number of States with Online and Phone Medicaid Applications and Real-Time Determinations, January 2016

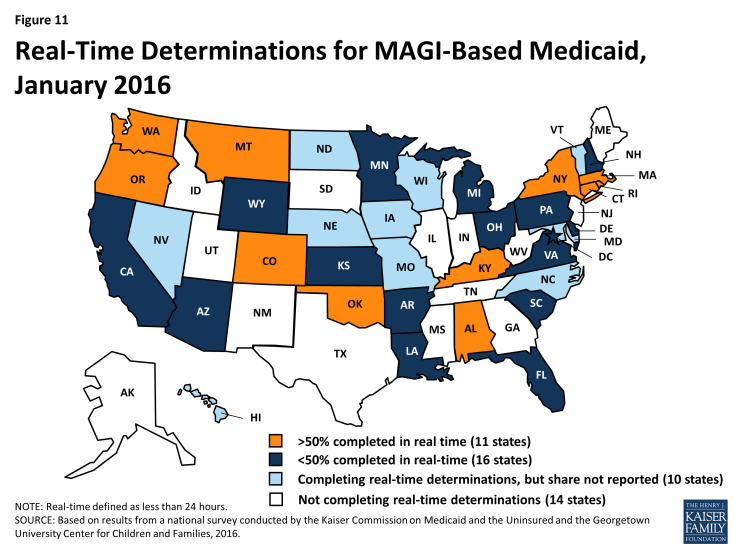

As of January 2016, 37 states report they can make real-time Medicaid eligibility determinations (defined as less than 24 hours) for children, pregnant women, and non-disabled adults. Among the 27 states that were able to report the share of applications for these groups that receive a real-time determination, 11 indicated that more than 50% of applications receive a determination in real time.

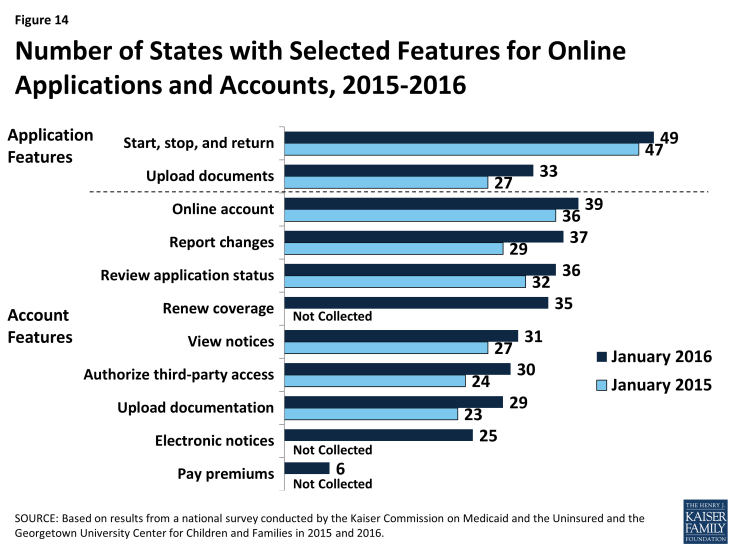

States expanded functionalities of online applications and accounts during 2015. Reflecting this work, all but one of the 50 online Medicaid applications allow applicants to start, stop, and return to the application, and 33 allow applicants to upload documents as of January 2016. In addition, 39 states allow consumers to create an online account to manage their Medicaid coverage. During 2015, a number of states expanded account functionalities, enabling consumers to report changes, view notices, upload documentation, renew coverage, and more.

Coordination between state Medicaid agencies and the Marketplaces improved during 2015, but challenges remain. Among the 17 states operating a SBM, 13 have a single integrated system that makes eligibility determinations for both Medicaid and Marketplace coverage, which eliminates the need for account transfers between programs. However, the 38 states that rely on the Federally Facilitated Marketplace (FFM), Healthcare.gov, for Marketplace eligibility and enrollment must electronically transfer accounts between Medicaid and the FFM to provide access to all insurance affordability programs. As of January 2016, all 38 states that rely on the FFM report they can receive electronic account transfers from the FFM, and 36 states report they can send electronic account transfers to the FFM. Twenty states report they are having problems or delays with transfers, although the scope of these problems varies across states. Although challenges remain, there has been marked improvement in coordination since the Marketplaces were launched in 2014, when states faced major technical difficulties with transfers that contributed to enrollment delays.

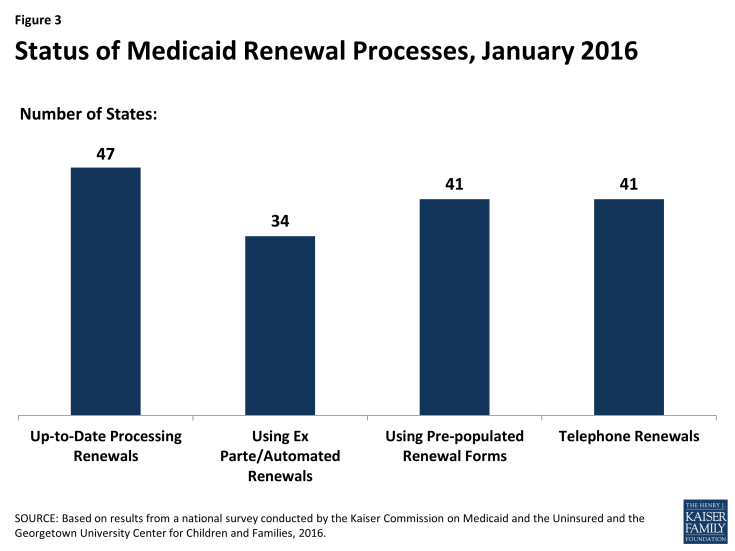

As implementation continues, a number of states eliminated delays in processing renewals and put streamlined renewal procedures in place as established by the ACA. When the ACA was first implemented, there was significant focus on implementing streamlined enrollment processes and establishing coordination between Medicaid and the new Marketplaces. As a result, most states delayed implementing new renewal procedures, and 36 states took up a temporary option to postpone renewals for existing Medicaid or CHIP enrollees during 2014. In 2015, most states caught up on renewals and many made gains in implementing streamlined renewal procedures. As of January 2016, 47 states are up to date in processing renewals for Medicaid (Figure 3). A total of 34 states report they can complete automatic or ex parte renewals by using information from electronic data sources, as outlined in the ACA. Among the 26 states that can report the share of renewals completed using automated processes, 10 indicate that over 50% of enrollees are automatically renewed, including 3 that report automatic renewal rates above 75%. In addition, 41 states can send pre-populated renewal forms, which states must use when they are unable to complete an automated renewal under ACA policies; 41 states offer telephone renewals as outlined by the ACA.

Premiums and Cost-Sharing

Premiums and cost-sharing in Medicaid and CHIP remain limited, although under waiver authority a few states are charging higher levels than otherwise allowed under federal law. The number of states charging premiums or enrollment fees (30 states) or copayments (26 states) for children remained the same during 2015. While most states charge nominal copayments for parents (40 states) and expansion adults (23 of 31 expansion states), states generally do not charge these groups premiums given that most of these individuals have incomes below poverty. However, as of January 2016, five states (Arkansas, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, and Montana) charge adults monthly contributions or premiums under Section 1115 waiver authority. Indiana also received approval to charge parents monthly contributions and, under separate Section 1916 waiver authority, to charge parents and adults higher cost-sharing for non-emergency use of the emergency room than otherwise allowed under federal law.

Looking Ahead

States’ Medicaid and CHIP eligibility policies and enrollment and renewal processes will play a key role in reaching the remaining low-income uninsured population and keeping eligible individuals enrolled over time. Together, these survey findings show that:

Medicaid and CHIP continue to be central sources of coverage for the low-income population, but access to coverage varies widely across groups and states. Medicaid and CHIP offer a base of coverage to low-income children and pregnant women nationwide. Eligibility for adults has grown under the Medicaid expansion, but remains low in states that have not expanded. Overall, eligibility continues to vary significantly by group and across states, resulting in substantial differences in individuals’ access to coverage based on their eligibility group and where they live.

Upgraded state Medicaid systems help eligible individuals connect to and retain coverage over time, provide gains in administrative efficiencies, and offer new options to support program management. One key outcome of the ACA has been the significant modernization of states’ Medicaid eligibility and enrollment systems. These higher-functioning systems help eligible individuals connect to coverage more quickly and easily, keep individuals enrolled over time, reduce paperwork burdens, and lead to increased administrative efficiencies. Moreover, the modernized systems offer new options to support program management. For example, states may have increased data reporting capabilities and expanded options to connect Medicaid with other systems. Further, as systems and processes become more refined over time, states may be able to manage enrollment more efficiently, which may allow them to refocus resources on other activities.

There remain key questions about how recent changes in eligibility and enrollment may be affected by a range of factors moving forward. Funding for CHIP is set to expire in 2017, raising key questions about the future of the program and what might happen in its absence. In addition, the ACA maintenance of effort provisions for children’s coverage end in 2019. State Medicaid expansion decisions will likely continue to evolve over time, and it remains to be seen how they might be affected by the gradual reduction in federal funding for newly eligible expansion adults, which begins to phase down in 2017 when it reduces to 95%. Pending proposals in current budget reconciliation legislation would roll back the Medicaid expansion to adults and eliminate the maintenance of effort requirements in 2017. Outside of these potential changes, it also will be important to examine how the Section 1115 waivers that allow states to charge adults premiums and monthly contributions are affecting coverage and program administration, particularly given that waiver authority is provided for research and demonstration purposes.

Report

Introduction

January 2016 marks the second anniversary of the effective date of the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA’s) key coverage provisions. During 2015, Medicaid and CHIP continued to be central sources of coverage for low-income children and pregnant women nationwide, and Medicaid’s role for low-income adults grew as a result of the ACA Medicaid expansion. At the end of the second full year of implementation of the ACA’s coverage expansions, states have continued to implement and enhance new and upgraded eligibility and enrollment systems that underpin the ACA’s vision for a modernized data-driven enrollment experience. States also worked to implement automated renewal processes and improve coordination between Medicaid and the Marketplaces, resolving many problems and delays faced during the initial year of ACA implementation.

This annual report presents Medicaid and CHIP eligibility, enrollment, renewal and cost-sharing policies based on a survey of state program officials. It provides a point-in-time snapshot of policies in place as of January 2016 and identifies changes in state policies that occurred between January 2015 and 2016. These changes provide insight into how state policies are evolving from the new baseline that was established at the end of 2014, after the first full year of ACA implementation. State-specific information is available in Tables 1 to 21 at the end of the report.

Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility

The ACA established a new minimum Medicaid eligibility level of 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL) for children, pregnant women, parents and non-disabled adults as of January 2014. This new minimum increased eligibility for parents in many states and provided a new eligibility pathway for other non-disabled adults who were largely excluded from Medicaid prior to the ACA. Although the expansion to adults with incomes up to 138% FPL was effectively made a state option by the Supreme Court’s 2012 ruling on the constitutionality of the ACA, the Court’s decision did not impact other eligibility changes in the law. As a result of the new 138% FPL minimum for children in Medicaid, some states moved certain children from CHIP to Medicaid. Moreover, all states implemented the ACA change to determine financial eligibility for Medicaid for children, pregnant women, parents, and non-disabled adults and CHIP based on Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI). This change created alignment with the method used for determining eligibility for subsidies to purchase Marketplace coverage. States continue to determine eligibility for other groups, such as individuals with disabilities and elderly individuals, based on previous non-MAGI-based rules.

The findings below show Medicaid and CHIP eligibility levels for children, pregnant women, parents, and other non-disabled adults as of January 2016 and identify changes in eligibility that occurred between January 2015 and January 2016. These data show that Medicaid and CHIP continue to be central sources of coverage for the nation’s low-income children and pregnant women, with some states adopting optional policies in 2015 that expand access to coverage for certain children and pregnant women. They also highlight the continued growth of Medicaid’s role for low-income adults through the ACA Medicaid expansion.

Children and Pregnant Women

Coverage for children in Medicaid and CHIP remains strong and steady with median eligibility at 255% FPL. Under the ACA’s maintenance of effort protections, states cannot make reductions in children’s eligibility through 2019. Reflecting this protection, there were no policy changes to children’s eligibility in 2015. However, in Kansas, the state’s CHIP eligibility level is tied to the 2008 FPL; thus, CHIP eligibility declined from 247% to 244% FPL and will continue to erode over time. As of January 2016, 48 states cover children with incomes up to at least 200% FPL through Medicaid and CHIP, including 19 states that cover children at or above 300% FPL (Figure 4). Across states, the upper Medicaid/CHIP eligibility limit for children ranges from 152% FPL in Arizona to 405% FPL in New York.

Mirroring previous action taken by California and New Hampshire in 2014, Michigan transitioned all children from its separate CHIP program into Medicaid as of January 2016. In contrast, Arkansas established a new separate CHIP program and moved children with family incomes from 147% to 216% FPL from its CHIP-funded Medicaid expansion to the new separate CHIP program. Enrollment remains open in all states with separate CHIP programs except in Arizona. Arizona froze enrollment in its separate CHIP program at the end of 2009, prior to enactment of the ACA eligibility protections.

States continued to take up options to enhance children’s access to coverage during 2015.

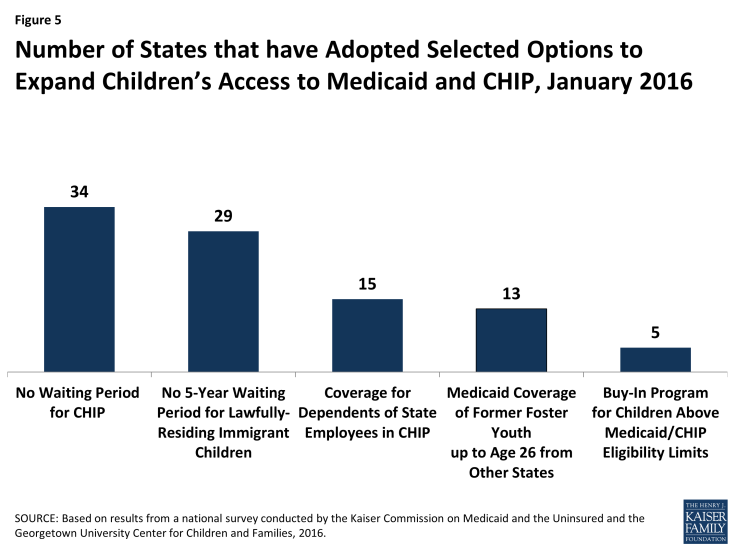

- Eliminating waiting periods for CHIP coverage. During 2015, Wisconsin eliminated its waiting period for its separate CHIP program. In addition, Michigan’s CHIP waiting period was eliminated when it transitioned all children from its separate CHIP program to Medicaid. With these changes, 24 states have eliminated waiting periods for CHIP since the ACA was enacted in 2010. As of January 2016, 34 states do not have a waiting period for CHIP coverage (Figure 5). However, 16 of the 36 states with separate CHIP programs have a waiting period that requires a child to be uninsured for a period of time prior to enrolling. These waiting periods may not exceed 90 days.

Figure 5: Number of States that have Adopted Selected Options to Expand Children’s Access to Medicaid and CHIP, January 2016

- Expanding coverage to recent lawfully residing immigrant children. With the addition of Colorado during 2015, 29 states have taken up the option to eliminate the five-year waiting period for lawfully present immigrant children in Medicaid and/or CHIP as of January 2016. In addition, six states (California, District of Columbia, Illinois, Massachusetts, New York, and Washington) use state-only funds to cover some income-eligible children regardless of immigration status.1 This count includes California, which has some local programs that cover children regardless of immigration status and recently passed legislation to cover children regardless of immigration status on a statewide basis starting in 2016.

- Expanding federally-funded CHIP coverage to dependents of state employees. As of January 2016, 2 additional states (Nevada and Virginia) took up the option to cover otherwise eligible children of state employees in a separate CHIP program, bringing the total number of states that have taken up this option to 15.

- Expanding coverage for former foster youth. Under the ACA, all states must provide Medicaid coverage to youth who were in foster care in the state up to age 26, but it is a state option to extend this coverage to former foster youth from other states. During 2015, New Mexico took up this option, raising the total number of states covering former foster youth from other states to 13 as of January 2016.

Following a trend since enactment of the ACA, the number of states offering buy-in programs for children in families above Medicaid or CHIP income limits continued to decline. States may offer buy-in programs to allow families with incomes above the upper limit for children’s coverage to buy-in to Medicaid or CHIP for their children. In 2015, North Carolina lifted the income limit on its buy-in program, while Connecticut eliminated its buy-in program. The number of states offering buy-in programs has declined from a peak of 15 in 2011 to 5 as of January 2016, reflecting that families above Medicaid and CHIP income thresholds may have new coverage options available through the Marketplaces.

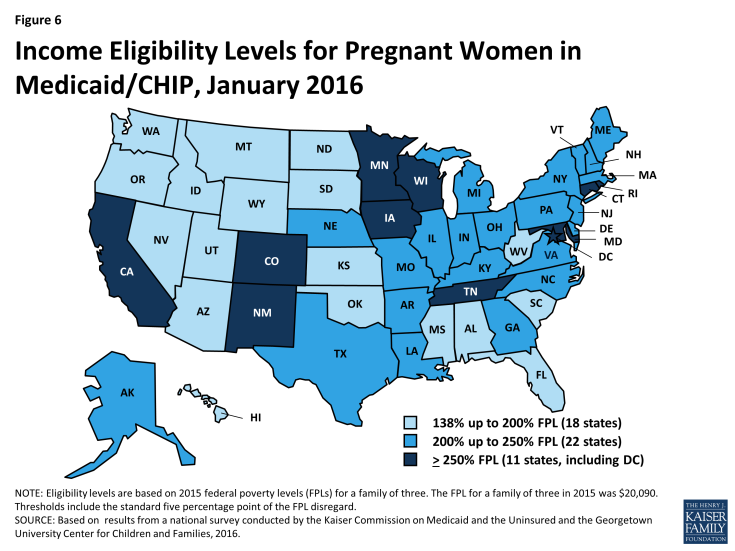

Coverage for pregnant women remained stable in 2015. The median eligibility level for pregnant women in Medicaid or CHIP held steady at 205% FPL, with eligibility ranging from 138% FPL in Idaho and South Dakota to 380% FPL in Iowa. Overall, 33 states cover pregnant women with incomes up to at least 200% FPL (Figure 6). The number of states that have eliminated the five-year waiting period for lawfully residing immigrant pregnant women in Medicaid and/or CHIP remained constant at 23. However, Colorado, which had previously covered recent lawfully-residing pregnant women in Medicaid, expanded this option to pregnant women in CHIP during 2015. The number of states covering income-eligible pregnant women regardless of immigration status through the CHIP unborn child option (15 states) or with state-only funds (3 states) remained unchanged.

Parents and Adults

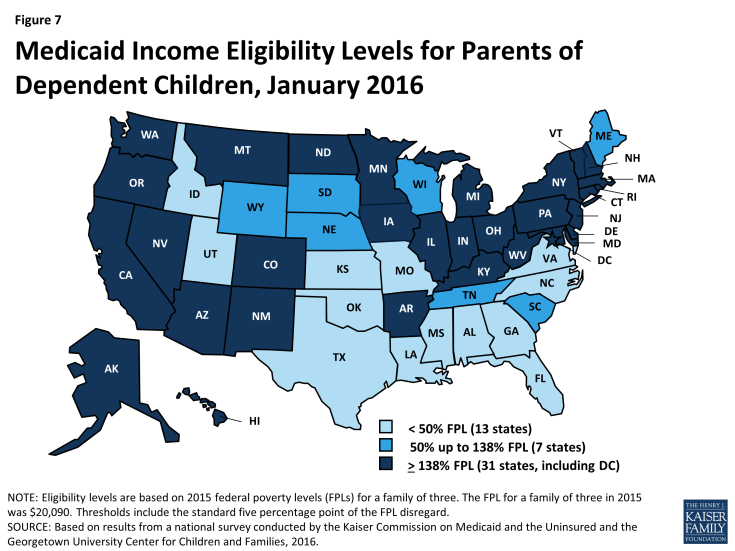

As of January 2016, 31 states, including the District of Columbia, have expanded Medicaid eligibility to parents and other non-disabled adults2 with incomes up to at least 138% FPL. This finding reflects adoption of the ACA Medicaid expansion to low-income adults in three states during 2015–Indiana, Alaska, and, most recently, Montana, where the expansion went into effect on January 1, 2016. Indiana and Montana joined four other states (Arkansas, Iowa, Michigan, and New Hampshire) that expanded Medicaid for adults under Section 1115 waiver authority, allowing them to implement the expansion in ways that extend beyond the flexibility provided by the law.3 During 2015, Pennsylvania moved from implementing its expansion through a waiver to regular expansion coverage, while New Hampshire moved from a regular expansion to a waiver as of January 2016. There is no deadline for states to adopt the Medicaid expansion, and additional states may expand in the future. Medicaid eligibility extends to parents and other adults with incomes up to at least 138% FPL in all 31 expansion states (Figures 7 and 8). Additionally, the District of Columbia covers parents up to 221% FPL and other adults up to 215% FPL. Connecticut reduced parent eligibility during 2015, lowering eligibility from 201% to 155% FPL. However, parent eligibility remains above the 138% FPL minimum, and many parents who lost Medicaid eligibility are likely eligible for subsidies to purchase Marketplace coverage.

As of January 2016, two states—Minnesota and New York—have implemented Basic Health Programs. The ACA provides an option for states to create a Basic Health Program (BHP) for low-income residents with incomes between 138% and 200% FPL, who would otherwise be eligible to purchase Marketplace coverage. Through this option, states provide alternative coverage that may cover more services or be more affordable than what is offered through the Marketplaces, which may reduce movement between plans and coverage types for people whose incomes fluctuate above and below Medicaid levels.4 New York’s BHP will be fully phased in as of January 2016, joining Minnesota as the second state with a BHP. When New York implemented its BHP, it stopped providing some additional Medicaid-funded subsidies to parents with incomes between 138% and 150% FPL who can now receive coverage through the BHP.

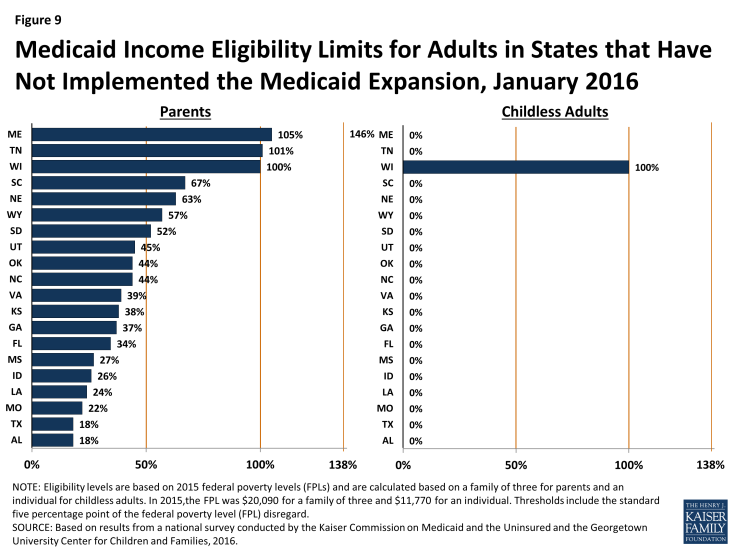

In the 20 states that have not expanded Medicaid, the median eligibility level for parents is 42% FPL; other adults remain ineligible regardless of income in all of these states except Wisconsin. Among the 2o non-expansion states, parent eligibility levels range from 18% FPL in Alabama and Texas to 105% FPL in Maine (Figure 9). Only 3 of these states—Maine, Tennessee, and Wisconsin—cover parents at or above 100% FPL, while 13 states limit parent eligibility to less than half the poverty level ($10,045 for a family of three as of 2015). Wisconsin is the only non-expansion state that provides full Medicaid coverage to other non-disabled adults, although its 100% FPL eligibility limit is lower than the ACA expansion level. While this study reports eligibility based on a percentage of the FPL, it also is important to note that 13 non-expansion states base eligibility for parents on dollar thresholds (which have been converted to an FPL equivalent in this report). Of those states, 12 do not routinely update the standards, resulting in eligibility levels that erode over time relative to the cost of living. Other analysis shows that three million poor adults fall into a coverage gap as a result of these low Medicaid eligibility levels in non-expansion states.5 These adults earn too much to qualify for Medicaid, but not enough to qualify for subsidies for Marketplace coverage, which are available only to those with incomes at or above 100% of FPL.

Figure 9: Medicaid Income Eligibility Limits for Adults in States that Have Not Implemented the Medicaid Expansion, January 2016

Eligibility levels for parents and other adults remain lower than those for children and pregnant women. Among expansion and non-expansion states, median eligibility levels for parents and other adults remain lower than those for pregnant women and children (Figure 10). In expansion states, median Medicaid and CHIP eligibility levels are 305% FPL for children and 213% FPL for pregnant women compared to 138% FPL for parents and other adults. However, these differences are more pronounced in states that have not implemented the Medicaid expansion. In the non-expansion states, the median Medicaid and CHIP eligibility level is 215% for children and 200% for pregnant women compared to 42% FPL for parents and 0% for other adults.

Medicaid and CHIP Enrollment and Renewal Processes

During 2015, states continued to implement system enhancements and adopt processes to implement the ACA’s vision of a modernized data-driven enrollment experience and a largely automated renewal process. Adoption of these procedures represents significant transformation and streamlining in many states that previously relied on paper-based enrollment and renewal processes for Medicaid and CHIP. As states continued work developing the information technology systems that underpin enrollment and renewal, their functionality increased as demonstrated by the growing number of states that are able to make real-time eligibility determinations and automatically renew coverage. Coordination between Medicaid and the Marketplaces also improved considerably in 2015, but there are lingering challenges to ensure smooth transitions between coverage programs for individuals.

Eligibility and Enrollment Systems

In order to implement the new enrollment and renewal processes outlined in the ACA, most states needed to make major improvements to or build new Medicaid and CHIP eligibility and enrollment systems and coordinate enrollment with the Marketplaces. To support system development, the federal government provided 90% federal funding for system design and development. This increased funding level was initially set to expire at the end of 2015, but CMS finalized a rule in December 2015 to extend the higher federal match permanently.1 The extension of this funding will support continued work in states that have not implemented enhanced system functionality to fully meet ACA requirements. It also will support continued state work to phase in additional capabilities and consumer features and keep systems current as technology evolves in the future. Higher functioning systems facilitate the ability to enroll and keep eligible individuals in coverage by reducing paperwork burdens and allowing individuals to manage more activities through an online environment. They also may contribute to increased administrative efficiencies. Moreover, as these systems and processes become more refined, they may enable states to manage larger enrollments more efficiently, allowing them to refocus resources on other services such as helping individuals understand how to use their health care services. They may also provide new tools and options to support program management, such as increased data reporting and data connections with other systems or programs.

As of January 2016, 37 states can complete MAGI-based eligibility determinations in real-time (defined as less than 24 hours), and 11 states indicate that at least 50% of MAGI-based applications receive a real-time determination. Among the 27 states that were able to report the percentage of MAGI-based applications that receive a real-time determination, 11 states report a success rate that exceeds 50%, including 9 that report a rate over 75%. In the remaining 16 states, less than half of MAGI-based applications receive a determination in real-time (Figure 11). Looking ahead, many states will continue to work to increase the share of applications that receive a real-time determination.

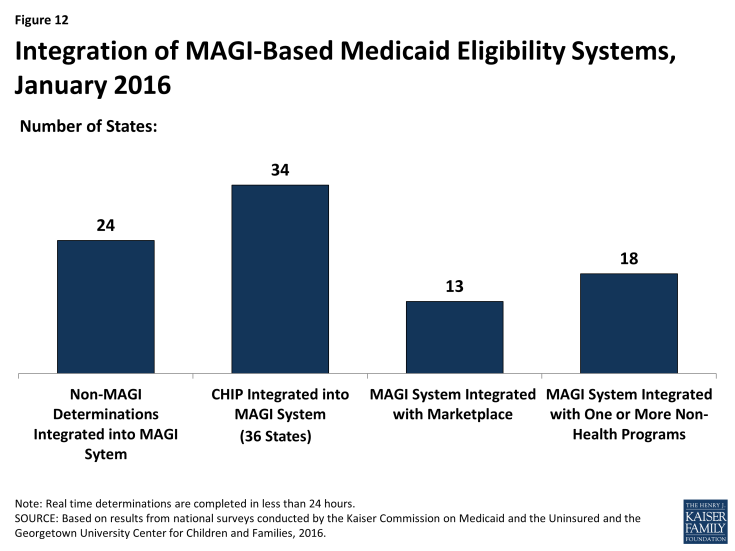

As of January 2016, states vary in the integration of other health programs in their MAGI-based Medicaid systems (Figure 12). During 2015, three states (Florida, Nebraska, and Virginia) integrated eligibility determinations for non-MAGI groups, which include elderly individuals and individuals with disabilities, into their MAGI-based systems. With these additions, 24 states process MAGI and non-MAGI groups through the same system as of January 2016. Most states with a separate CHIP program (34 of 36 states) have CHIP integrated into the MAGI-based system. Among the 17 states operating a State Based Marketplace (SBM), 13 have a single, integrated system that makes eligibility determinations for both MAGI-based Medicaid and Marketplace coverage. With Hawaii transitioning eligibility determinations from its SBM to the Federally Facilitated Marketplace (FFM) in 2015, 4 SBM states and the 34 FFM and Partnership states are using Healthcare.gov for Marketplace eligibility and enrollment functions as of January 2016. These 38 states all must maintain a separate Medicaid eligibility and enrollment system at the state level.

In 18 states, the MAGI-based Medicaid system is integrated with at least one non-health program, and a number of states are planning further integration in the future. Prior to the implementation of the ACA, 45 states had integrated systems to determine eligibility for Medicaid and other non-health programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP or food stamps), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), and childcare assistance. As states upgraded or built new Medicaid eligibility systems, many delinked these programs from the Medicaid system due to the large scale of the changes. However, as of January 2016, 18 states had integrated at least one non-health program into their MAGI-based Medicaid system. Colorado delinked non-health programs from its Medicaid system when it integrated its Medicaid system with its Marketplace system in 2015. However, a number of states plan to phase in additional non-health programs into their Medicaid system in 2016 or beyond. The continuation of enhanced funding for system development, as well as flexibility provided by CMS that requires other programs to pay only the incremental integration costs, support these efforts. Although this flexibility was slated to end at the close of 2015, CMS extended it for three more years.2

Coordination between Medicaid and Marketplace systems improved considerably in 2015, but there are lingering challenges. In the 38 states relying on the FFM for Marketplace eligibility and enrollment functions, electronic accounts must be transferred between the federal and state systems to provide a coordinated, seamless enrollment experience for individuals as envisioned by the ACA. Such transfers are not necessary in the 13 SBM states with an integrated Medicaid and Marketplace eligibility system although, in some cases, data transfers must occur after the eligibility determination to complete enrollment. Among the 38 states relying on the FFM for eligibility and enrollment, 8 states have authorized the federal system to make final Medicaid eligibility determinations, which can expedite the enrollment process. However in these states, the FFM still must transfer accounts to the Medicaid agency to complete enrollment. The remaining 30 states allow the FFM to assess rather than determine Medicaid eligibility. These counts reflect three states (Louisiana, North Dakota, and Oregon) choosing to rely on the FFM for assessments rather than final determinations, and one state (Alaska) adopting the option for the FFM to make final determinations rather than assessments during 2015. States relying on the FFM for assessments must use the information received in the account transfer to determine eligibility based on the same verification requirements in place for individuals who apply directly through the state Medicaid agency. This process may require checking other data sources or requesting documentation for information that cannot be confirmed electronically. During 2014, there were significant difficulties with account transfers that contributed to delays in Medicaid enrollment. However, there have since been improvements in transfer functionality with all 38 states that rely on the FFM for Marketplace eligibility and enrollment functions reporting that they are receiving electronic account transfers from the FFM, and 36 states reporting that they are sending electronic account transfers to the FFM as of January 2016. A little more than half of these states (20 states) report they are still experiencing some delays or difficulties with transfers, although the scope of these challenges varies across these states.

Applications

Under the ACA, states must provide multiple methods for individuals to apply for health coverage, including online, by phone, by mail, and in person, using a single streamlined application for Medicaid, CHIP, and Marketplace coverage. The use of online applications, as well as online accounts, gives states new opportunities to offer features and functions that enhance individuals’ enrollment experience and expand their ability to manage their ongoing Medicaid coverage, which may help eligible individuals enroll and retain coverage over time. The increased use of technology may also provide administrative efficiencies to states by reducing paperwork and manual input of information that enrollees can report online, such as an address change. This growth in the use of technology has been supported by the 90% federal match for systems development and 75% federal match for ongoing operations that are now permanently available to states.

As of January 2016, individuals can apply online or by phone for Medicaid in nearly all states. In all states, except Tennessee, there is an online Medicaid application available through the state Medicaid agency or, in SBM states, an integrated portal that provides access to Medicaid and the SBM. In addition, 24 states offer an integrated online application that allows individuals to apply for Medicaid and non-health programs, such as SNAP or TANF. These states largely align with those states that have Medicaid and non-health programs integrated into a single eligibility system, although a few states are using separate eligibility systems to process multi-benefit applications. With the addition of Arkansas and Florida during 2015, 49 states are accepting Medicaid applications by phone as of January 2016. The number of states providing online and telephone Medicaid applications has significantly increased since initial implementation of the ACA changes in 2014 (Figure 13).

A number of states expanded the functionality of online applications and accounts during 2015. Between January 2015 and 2016, the number of states that provide applicants the option to start, stop, and return to complete their application at a later time increased from 47 to 49, while the number of states that allow applicants to upload electronic copies of documentation through the online application increased from 27 to 33 (Figure 14). In addition, the number of states that provide individuals the opportunity to create an online account for ongoing management of their Medicaid coverage rose from 36 to 39, with the addition of North Dakota, South Carolina, and South Dakota. A larger number of states added features to existing online accounts. Specifically, there were increases in the number of states that allow individuals to use their online account to report changes (29 to 37 states), review the status of their application (32 to 36 states), view notices (27 to 31 states), authorize third-party access (24 to 30 states), and upload documentation (23 to 29 states). This year’s survey also asked about additional account functionalities and found that individuals can use their account to renew coverage in 35 states, go paperless and receive electronic notices in 25 states, and pay premiums in 6 of the 32 states that charge premiums in Medicaid or CHIP. Additional states plan to add online accounts in 2016 or beyond, while states with online accounts plan to continue to add features. These online functions provide timely and convenient access to account information that is commonplace in today’s digital age, and may lead to administrative efficiencies by reducing mailing costs, call volume, and manual processing of updates. The ability for consumers to see and manage their application and information online also may contribute to increased enrollment and retention levels over time.

Nearly half of the states (24 states) provide a web portal or secure login for authorized consumer assisters to submit applications they have facilitated on behalf of consumers. In some cases, these portals provide additional administrative features that support the work of assisters, such as the ability to check a renewal date or update an address. Providing better tools for assisters may reduce state administrative workloads and free resources for other consumer services. This functionality may also allow the agency to track, monitor and report application activity by assister more thoroughly, accurately, and efficiently.

Verification of Eligibility Criteria

Under the ACA, all states must verify income eligibility and citizenship or immigrant status but they have flexibility to accept self-attestation for other criteria such as age/date of birth, state residency, and household composition. If verification is required, states are expected to use electronic data sources to the extent possible. Verifying eligibility criteria electronically is not only technically complicated, but requires the establishment of data sharing agreements between agencies to ensure that the privacy and security of personally identifiable information is protected. These challenges in accessing electronic data sources can slow state progress in implementing or maximizing real-time eligibility determinations and automated renewals without the intervention of an eligibility worker. However, as of 2016, a number of states are reporting success completing real-time eligibility determinations and automatic renewals that are facilitated through electronic data matches.

States are relying on a mix of data sources to electronically verify eligibility criteria. To facilitate electronic verification, a federal data hub was established that allows states to access information from multiple federal agencies, including the Internal Revenue Service, the Social Security Administration (SSA), and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), which is used by almost three quarters of states. States not using the federal hub rely on pre-ACA linkages to SSA and DHS databases. Nearly all states also use state databases that collect quarterly state wage information or unemployment compensation, which may contain more current income information. About half of the states also use information from their state vital records while a smaller number of states access information from other state databases, such as the Department of Motor Vehicles or State Tax Department.

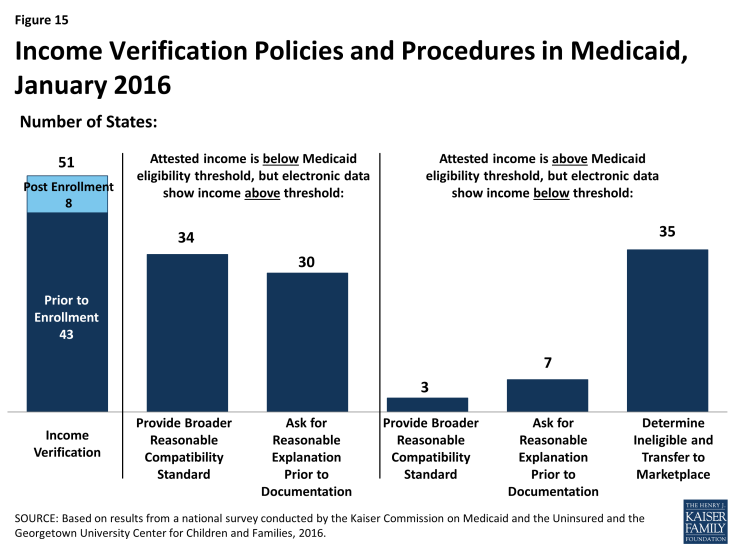

As of January 2016, 43 states use electronic data sources to verify income prior to enrollment, while 8 states verify after enrollment (Figure 15). States are required to verify income electronically either prior to or after enrollment and may apply “reasonable compatibility standards” to account for differences in self-reported income and data from electronic sources. If self-reported income and the data from the electronic source are both above or below the Medicaid or CHIP eligibility threshold, states must disregard the discrepancy since it does not impact eligibility. States have the option to establish broader reasonable compatibility standards, which 34 states have adopted for cases in which self-attested income is below but electronic data sources show income above the Medicaid or CHIP eligibility limit. If the difference is within this reasonable compatibility standard, which is most often 10%, states accept the self-reported income. In contrast, only three states (Colorado, Florida and New Jersey) have adopted a reasonable compatibility standard for when self-reported income is above the income standard but the electronic data source is below. In these circumstances, 35 states deny Medicaid or CHIP eligibility and transfer the account for an assessment of Marketplace eligibility. Regardless of whether they have set broader reasonable compatibility standards, states may accept a reasonable explanation of the difference (e.g., the individual lost a job) in lieu of requiring paper documentation.

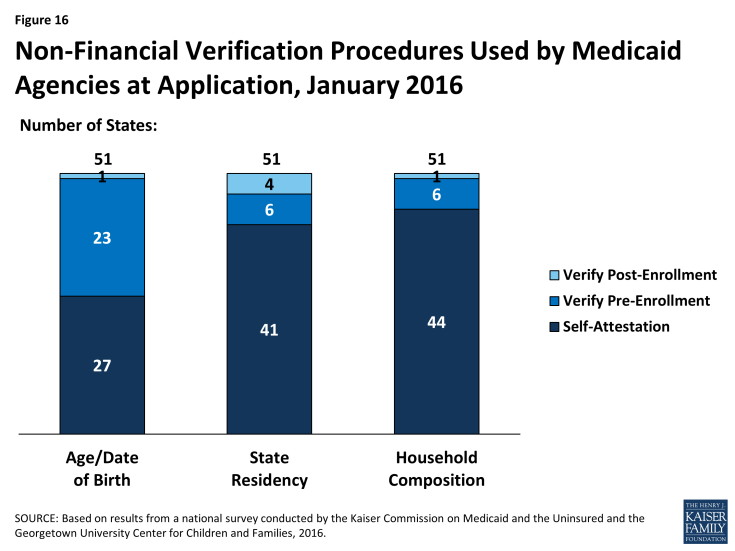

States’ procedures to verify non-financial eligibility criteria continue to evolve as their systems and electronic verification capacity develop. For non-financial eligibility criteria, including age/date of birth, state residency, and household composition, states may accept self-attestation or verify either before or after enrollment. Accepting self-attestation expedites the process for states and applicants, particularly when the state lacks access to trusted data sources that can be used for verification purposes. For states that rely on self-attestation, verification is required if a state has any information on file that conflicts with the self-attestation. As of January 2016, just over half of the states accept self–attestation of age/date of birth (27 states), while a majority of states do so for state residency (41 states) and household size (44 states) (Figure 16). The remaining states verify these eligibility criteria either prior to enrollment or post-enrollment, and about half of those states re-verify the information at renewal.

Figure 16: Non-Financial Verification Procedures Used by Medicaid Agencies at Application, January 2016

Facilitated Enrollment Options

States vary in their use of policy options to streamline enrollment. As states achieve high rates of real time eligibility determinations, the reliance on facilitated enrollment options may decline. However, there will always be some individuals who may benefit from expedited paths to enrollment since not all individuals will be able to have eligibility verified in real time. As of January 2016, states continue to rely on a range of these policy options to provide facilitated access to coverage as discussed below.

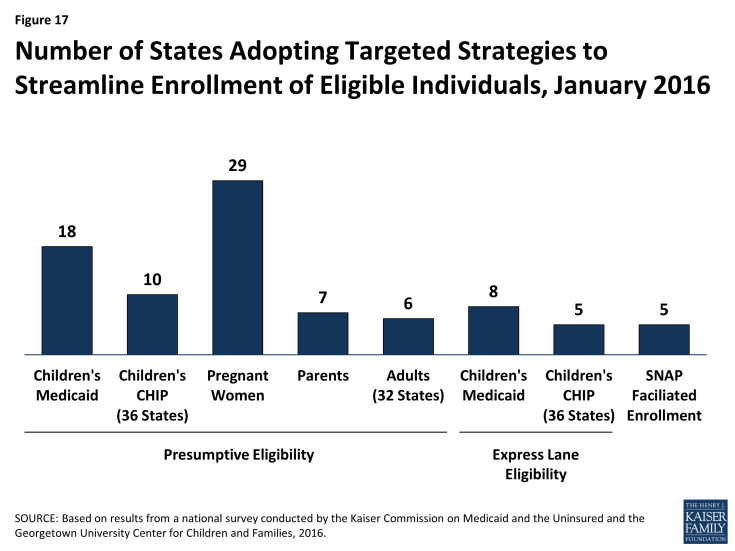

- Presumptive eligibility. Presumptive eligibility is a longstanding option in Medicaid and CHIP, which allows states to authorize qualified entities—such as community health centers or schools—to make a temporary eligibility determination to expedite access to care for children and pregnant women while the regular application is being processed. The ACA broadened the use of presumptive eligibility in two ways. First, the law allows states that use qualified entities to presumptively enroll children or pregnant women to extend the policy to parents, adults, and other groups. As of January 2016, 18 states use presumptive eligibility for children in Medicaid, 10 for children in CHIP, 29 for pregnant women, 7 for parents, and 6 for other adults (Figure 17). This count reflects expansion of the use of presumptive eligibility to parents and adults in Colorado and Montana; to children in Medicaid and CHIP, parents, and adults in Indiana; and to pregnant women in Kansas during 2015. Second, the ACA gives hospitals nationwide the authority to determine eligibility presumptively for Medicaid for all non-elderly, non-disabled individuals. Hospital-based presumptive eligibility has been implemented in 45 states as of January 2016.

Figure 17: Number of States Adopting Targeted Strategies to Streamline Enrollment of Eligible Individuals, January 2016

- Express Lane Eligibility. Express Lane Eligibility (ELE) is another pre-ACA option that allows states to enroll children in Medicaid or CHIP based on findings from other programs, like SNAP. During 2015, Oregon discontinued the use of ELE, while Iowa began using ELE to enroll CHIP eligible children. Following this state action, eight states (Alabama, Colorado, Georgia, Iowa, Louisiana, New Jersey, New York, and South Carolina) use ELE to enroll children in Medicaid, and five states (Colorado, Georgia, Iowa, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania) use ELE to enroll CHIP eligible children as of January 2016.

- Facilitated enrollment using SNAP data. In 2013, CMS offered states new temporary facilitated enrollment options, including using SNAP data to identify and enroll eligible individuals and using child enrollment data to expedite parent enrollment. In 2015, CMS made the SNAP facilitated enrollment option permanent.3 As of January 2016, five states (Arkansas, California, New Jersey, Oregon, and South Dakota) are using the facilitated SNAP enrollment strategy. Given that analysis has shown that facilitated enrollment strategies contribute to success enrolling newly eligible adults and children and reducing administrative costs,4 other states may consider adopting the SNAP enrollment practice now that it is a permanent state option.

Renewal Processes

Many states eliminated delays in renewals during 2015. When the ACA was initially implemented, states and the federal government focused heavily on implementing streamlined enrollment processes and establishing coordination between Medicaid and Marketplace coverage. As a result, most states were delayed in implementing the new renewal procedures and 36 states took up a temporary option to postpone renewals for existing Medicaid or CHIP enrollees during 2014.5 During 2015, most states caught up on renewals. As of January 2015, 47 states reported that they are up to date in processing Medicaid renewals.

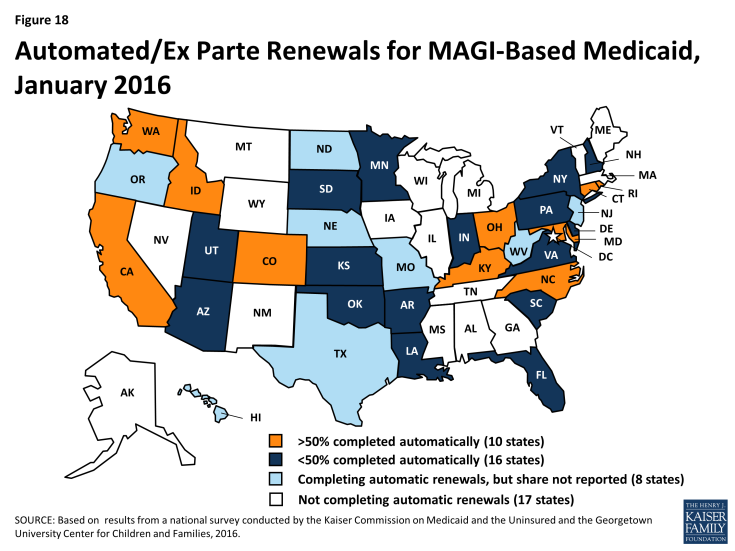

States continued to implement streamlined renewal processes, with 34 states using automated renewal processes as of January 2016, including 10 states that automatically verify ongoing eligibility for more than half of MAGI-based renewals. Similar to data-driven enrollment processes, the ACA requires states to first use available data to determine if ongoing eligibility can be established without requiring the individual to fill out a renewal form or provide paper documentation. As of January 1, 2016, 34 states are using this automated renewal process—known as ex parte. Not all of these states were able to report the share of renewals that are automatically renewed through this process. However, among the 26 states that did report this data, 10 states reported that they are successfully renewing more than 50% of enrollees automatically, with 3 achieving automatic renewals rates above 75% (Figure 18). Under ACA policies, if a renewal cannot be completed automatically based on data, states must send the enrollee a pre-populated notice or renewal form. As of January 2016, 41 states report they are able to send forms or notices that are pre-populated with information (beyond demographics), and 14 states use updated sources of data to populate the form. As is the case with enrollment, the ACA also requires states to provide individuals the option to renew their coverage by telephone. As of January 2016, 41 states provide this renewal option.

States continue to use other policy tools to boost retention.

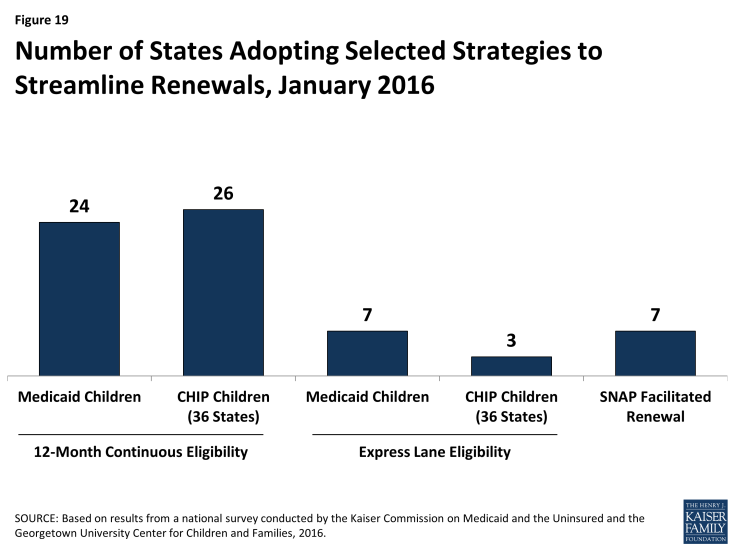

- 12-month continuous eligibility. The ACA established a new policy that requires states to renew coverage no more frequently than once every 12 months. However, enrollees still are required to report changes and will lose coverage if these changes make them ineligible. One way states can provide more stable coverage over time is to provide 12-month continuous eligibility, which provides a full year of coverage regardless of changes in income or household size. This policy promotes retention and improves the ability of states to measure quality. It also reduces the number of people moving on and off of coverage due to small changes in income and lowers state administrative costs that result from processing small changes in income. States have an option to adopt 12-month continuous eligibility for children, but must obtain a waiver to provide it to other groups. As of January 2016, 24 states provide 12-month continuous eligibility to children in Medicaid, while 26 of 36 states with a separate CHIP program have adopted the policy, including Arkansas for its newly established separate CHIP program (Figure 19). In addition, as of January 2016, New York and Montana provide 12-month continuous eligibility to parents and other adults under Section 1115 waiver authority.

- Express Lane Eligibility and Facilitated Renewal Using SNAP data. As is the case at enrollment, states can use ELE to streamline renewals. With the addition of Colorado, as of January 2016, 7 states (Alabama, Colorado, Iowa, Louisiana, Massachusetts, New York, and South Carolina) use ELE at renewal for children in Medicaid, and 3 of the 36 states with separate CHIP programs (Colorado, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania) use ELE for CHIP renewals. In addition, Massachusetts uses ELE to renew parents and other adults in Medicaid under Section 1115 waiver authority. The new option or waiver to use SNAP data to expedite enrollment of eligible individuals also applies to using SNAP data to renew coverage for enrollees. As of January 2016, seven states (Alaska, Arkansas, New Jersey, Oregon, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Virginia) are using SNAP data to renew Medicaid coverage under the waiver or option.

Premiums and Cost-Sharing

Given that additional expenses can strain the budgets of low-income individuals and families, federal rules in Medicaid and CHIP set limits on the amounts that states can charge for premiums and cost-sharing, including copayments, coinsurance, and deductibles (see Box 1). In light of this, premiums and cost-sharing generally remain low in Medicaid and CHIP as of January 1, 2016, with few changes in 2015. However, under Section 1115 waiver authority, several states have implemented monthly contributions or premiums for adults that would not otherwise be allowed under federal rules.

| Box 1: Premium and Cost-sharing Rules for Medicaid and CHIP |

| States have flexibility to impose premiums and cost-sharing in Medicaid. The maximum allowable charges vary by income and coverage group within federal rules:

Premiums in Medicaid. Medicaid enrollees, including children, pregnant women, parents and the adult expansion group, with incomes below 150% FPL may not be charged premiums. Premiums are allowed for Medicaid enrollees (both children and adults) with incomes above 150% FPL. Cost-sharing in Medicaid. Children with incomes below 133% FPL generally cannot be charged cost-sharing. Cost-sharing is allowed for adults enrolled in Medicaid, but charges for those with incomes below 100% FPL are limited to nominal amounts. Cost-sharing cannot be charged for preventive services for children or emergency, family planning, or pregnancy-related services in Medicaid. Under the ACA, preventive services defined as essential health benefits in Alternative Benefit Plans (ABP) in Medicaid also are exempt from cost-sharing for any individual enrolled in an ABP. Out-of-pocket limit in Medicaid. Overall premium and cost-sharing amounts for family members enrolled in Medicaid may not exceed five percent of household income. Premiums and Cost-sharing in CHIP. States have somewhat greater flexibility to charge premiums and cost-sharing for children covered by CHIP, although there remain federal limits on the amounts that can be charged, including an overall cap of five percent of household income. See: Premiums, Copayments, and other Cost-Sharing at http://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/by-topics/cost-sharing/cost-sharing.html |

Premiums and Cost-Sharing For Children

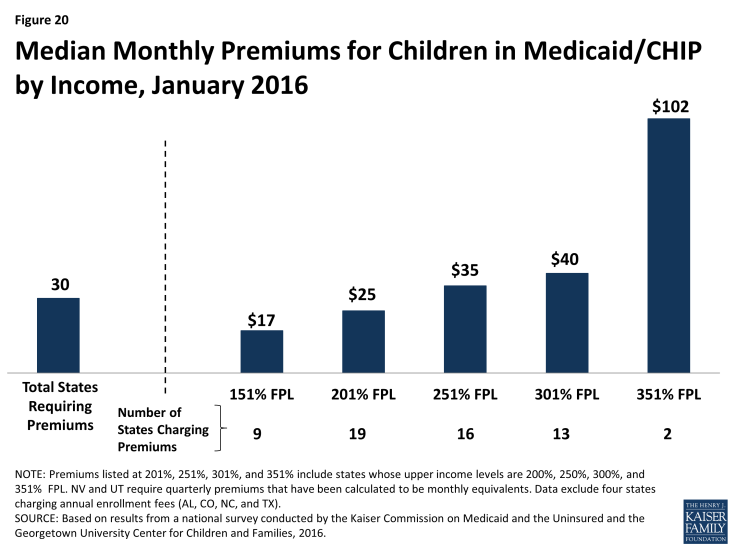

As of January 2016, 30 states charge premiums or enrollment fees for children in Medicaid or CHIP. Reflecting the ACA eligibility protections for children that extend through 2019, this count remained steady during 2015 as did most premium amounts. Under the ACA protections, states generally cannot increase premium amounts. One exception to this protection is if a state had a routine premium adjustment approved in its state Medicaid or CHIP plan prior to the enactment of the ACA on March 23, 2010. During 2015, two states (Maryland and Pennsylvania) increased premiums under such routine annual adjustments. Other changes included Michigan joining the three other states (California, Maryland and Vermont) that charge monthly premiums to children in Medicaid when it shifted all children from its separate CHIP program to Medicaid. Premiums and enrollment fees are more prevalent in CHIP than Medicaid due to the relatively higher incomes of families with children covered under CHIP and the program’s more flexible premium rules. 1 Overall, 26 states charge monthly or quarterly premiums and 4 charge annual enrollment fees for children in Medicaid or CHIP. In the 26 states charging monthly or quarterly premiums, charges begin for families above 150% FPL in 19 states, including 8 states in which charges begin above 200% FPL. Median monthly premium amounts range from $17 at 151% FPL to $102 at 351% FPL, although only two states extend eligibility up to this level (Figure 20).

States vary in their policies for nonpayment of premiums. States must provide a minimum 60-day grace period in Medicaid before cancelling coverage for nonpayment of premiums and cannot require enrollees to repay outstanding premiums as a condition of reenrollment, nor can they delay reenrollment. In contrast, CHIP programs are required to provide only a minimum 30-day grace period and may impose up to a 90-day lockout period during which time a child is not allowed to reenroll. Among the 22 states that charge monthly or quarterly premiums or enrollment fees in CHIP, only 4 states limit the grace period to the minimum 30 days, while 17 states provide a 60-day or longer grace period. With the addition of New Jersey in 2015, 14 CHIP programs have a lock-out period after a child is disenrolled for nonpayment of premiums, which range from 1 month to the maximum 90 days. Sixteen states that charge monthly or quarterly payments in Medicaid or CHIP require children who have been disenrolled due to nonpayment of premiums to reapply for coverage. However, seven states reinstate coverage retroactively if outstanding premiums are repaid.

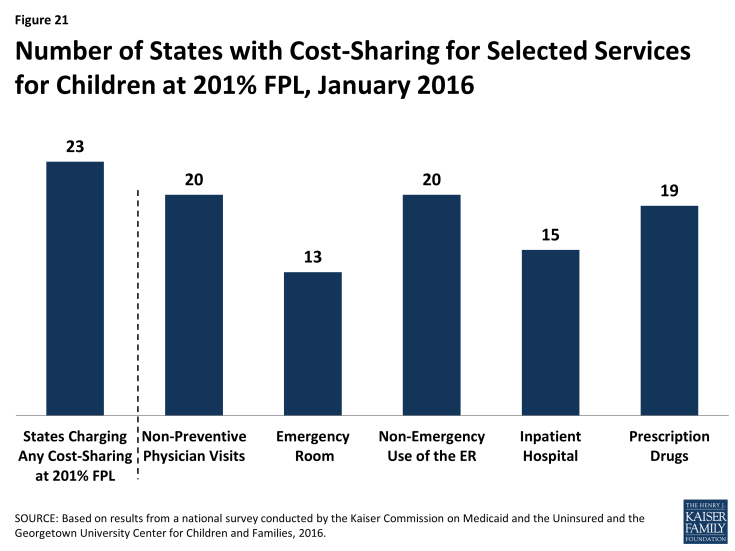

The number of states (26 states) charging cost-sharing for children in Medicaid or CHIP, as well as the amounts of copayments remained largely constant in 2015. As of January 2016, only three states charge cost-sharing for children in Medicaid, while 25 of the 36 states with separate CHIP programs charge cost-sharing. The number of states charging cost-sharing for children did not change in 2015; however, the data reflect Arkansas’ transition of children who were subject to cost-sharing in Medicaid to its new separate CHIP program. Only Tennessee charges cost-sharing for children in families with incomes below 133% FPL; under Section 1115 waiver authority, cost-sharing for children starts at the poverty level in the state. Copayments vary by service type. For example, for a child with family income at 201% FPL, 20 states charge cost-sharing for a physician visit, 13 charge for an emergency room visit, 20 charge for non-emergency use of the emergency room, 15 charge for an inpatient hospital visit, and 19 have charges for prescription drugs, although, in some cases, charges only apply to brand name or non-preferred brand name drugs (Figure 21).

Figure 21: Number of States with Cost-Sharing for Selected Services for Children at 201% FPL, January 2016

Premiums and Cost-Sharing for Parents and Other Adults

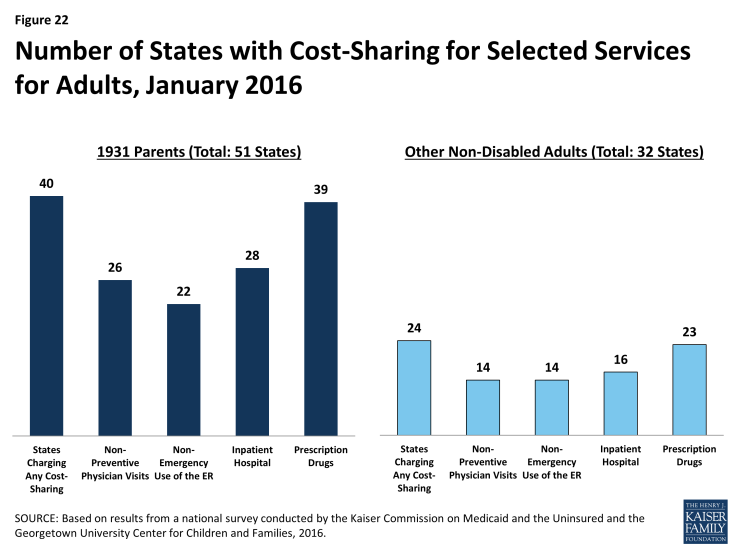

As of January 2016, states generally do not charge premiums for low-income parents in Medicaid, but many do have cost-sharing for these parents. Because most parents covered through the Section 1931 eligibility pathway that existed pre-ACA have incomes below poverty, states generally do not charge them monthly premiums. However, during 2015, Indiana implemented monthly contributions for Section 1931 parents under waiver authority, although enrollees cannot be disenrolled due to nonpayment. Forty states charge nominal cost-sharing for Section 1931 parents in Medicaid which varies by service. As of January 2016, 26 states charge parents cost-sharing for a physician visit, 22 charge for non-emergency use of the emergency room, 28 charge for an inpatient hospital visit, and 39 charge for prescription drugs, which may be limited to brand name drugs in some cases (Figure 22). Indiana is the only state to obtain Section 1916(f) waiver authority to charge parents higher cost-sharing than otherwise allowed, which applies to non-emergency use of the emergency room. Cost-sharing for parents remained stable in 2015 with a few exceptions: Florida and Oklahoma increased and Montana decreased cost-sharing for some services, and New York raised the income level at which cost-sharing begins from 0% to 100% FPL.

There are no premiums for expansion adults in 26 of the 31 states that have implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion, but 5 states charge premiums or monthly contributions under Section 1115 waiver authority as of January 2016. Specifically, Arkansas, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, and Montana charge premiums and/or monthly contributions for adults with incomes above poverty. The consequences of nonpayment of these charges vary across these states. Indiana and Montana can disenroll adults above poverty due to unpaid amounts and impose a lock-out period for those disenrolled. Iowa can also disenroll adults with incomes above poverty; however, it must waive the charges for individuals who self-attest to financial hardship and individuals can reenroll at any time. In Arkansas, monthly contributions are in lieu of point-of-service copayments; adults who do not make monthly contributions are responsible for point-of-service cost-sharing charges. The waivers in Arkansas, Iowa, Indiana, and Montana also allow the states to collect monthly contributions from individuals with incomes below poverty, although Arkansas has not implemented monthly contributions at this income level as of January 2016. Individuals with incomes below poverty cannot be disenrolled due to nonpayment. (See Box 2 for more details).

As of January 2016, 23 of the 31 states that have expanded Medicaid charge expansion adults cost-sharing. In addition, Wisconsin charges the adults it covers up to 100% FPL cost-sharing. Most states have aligned cost-sharing policies for adults and Section 1931 parents, although there are differences in some states. Cost-sharing amounts are generally nominal reflecting the low incomes of adults. Overall, 14 states charge cost-sharing for a physician visit, 14 charge for non-emergency use of the emergency room, 16 charge for an inpatient hospital visit, and 23 charge for prescription drugs as of January 2016. There were few changes in cost-sharing in the past year. These changes included some increases in copayments in New Hampshire and New York raising the income at which cost-sharing begins from 0% to 100% FPL.

| Box 2: Premiums/Monthly Contributions for Adults Under Section 1115 Waiver Authority |

|

Arkansas received waiver approval to require certain enrollees to make monthly income-based contributions to health savings accounts (HSAs) to be used in lieu of paying point-of-service copayments and co-insurance. Medically-frail individuals, including those with disabilities or complex health conditions, are exempt from these payments. Monthly contributions are $10 for expansion adults with incomes between 101% – 115%, and $15 for individuals with incomes between 116% – 138%. Under the waiver, Arkansas can charge monthly HSA contributions for expansion adults with incomes down to 50% FPL, but the state is not currently charging those with incomes below poverty. Adults with incomes above poverty who fail to make monthly HSA contributions are responsible for copayments and co-insurance at the point of service, and providers can deny services for failure to pay cost-sharing. Cost-sharing charges are at amounts otherwise allowed under federal law. In Iowa, the waiver allows the state to impose monthly contributions of $5 per month for non-medically frail beneficiaries with incomes between 50% and 100% FPL and $10 per month for non-medically frail beneficiaries with incomes above poverty beginning as of the second year of enrollment. The state cannot disenroll individuals below poverty due to unpaid premiums. Individuals above poverty have a 90-day grace period to pay past-due premiums before they are disenrolled, and the state must waive premiums for enrollees who self-attest to financial hardship. Individuals who are disenrolled for nonpayment can reenroll at any time. The waiver in Indiana imposes monthly contributions at 2% of income for most newly eligible adults and Section 1931 parents. Those with incomes between 0% and 5% FPL must pay $1.00 per month. Individuals with incomes below poverty cannot be disenrolled due to nonpayment but receive a more limited benefit package and are subject to copayments at the point of service. (Medically frail individuals are not placed in the more limited benefit package.) Individuals above poverty are not enrolled in coverage until they make their first monthly payment. In addition, non-medically frail individuals above poverty can be disenrolled due to nonpayment after a 60-day grace period and are subject to a 6-month lock-out period. Michigan’s waiver provides for monthly premiums of 2% of income for enrollees with incomes above poverty, as well as monthly payments into HSAs based on their prior six months of copayments for services used. The copayments are at the same level as what would have been collected without the waiver. Enrollees cannot lose or be denied Medicaid eligibility, be denied health plan enrollment, or be denied access to services, and providers may not deny services for failure to pay copayments or premiums.2 In Montana, non-medically frail expansion adults with incomes above 50% FPL are subject to monthly premiums of 2% of income. Enrollees receive a credit in the amount of their premiums toward copayments incurred, so that they effectively only have to pay copayments that exceed 2% of income. Those with incomes above poverty can be disenrolled for nonpayment after notice and a 90-day grace period and can reenroll upon payment of arrears or after the debt is assessed against their state income taxes, no later than the end of the calendar quarter. Reenrollment does not require a new application, and the state must establish a process to exempt beneficiaries from disenrollment for good cause. Individuals below poverty cannot be disenrolled for nonpayment of premiums.

Source: M. Musumeci and R. Rudowitz, “The ACA and Medicaid Expansion Waivers,” The Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, November 2015, available at https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-aca-and-medicaid-expansion-waivers/ |

Looking Ahead

States’ Medicaid and CHIP eligibility policies and enrollment and renewal processes will play a key role in reaching the remaining low-income uninsured population and keeping eligible individuals enrolled over time. Together, these survey findings show that:

Medicaid and CHIP continue to be central sources of coverage for the low-income population, but access to coverage varies widely across groups and states. Medicaid and CHIP offer a base of coverage to low-income children and pregnant women nationwide. Eligibility for adults has grown under the Medicaid expansion, but remains low in states that have not expanded. Overall, eligibility continues to vary significantly by group, with coverage available to children and pregnant women at higher income levels relative to parents and other adults. Eligibility also varies across states, and these differences have increased as a result of state Medicaid expansion decisions. Given this variation, there are substantial differences in individuals’ access to coverage based on their eligibility group and where they live.

Upgraded state Medicaid systems help eligible individuals connect to and retain coverage over time, provide gains in administrative efficiencies, and offer new options to support program management. One key outcome of the ACA has been the significant modernization of states’ Medicaid eligibility and enrollment systems. Although state implementation of new eligibility systems got off to a rocky start in 2014, as of 2016, states have implemented system enhancements and processes to increasingly support real-time, data driven eligibility determinations and automatic, paperless renewals of coverage as envisioned by the ACA. The higher-functioning systems in states help eligible individuals connect to coverage more quickly and easily, keep eligible individuals enrolled over time, reduce paperwork burdens, and lead to increased administrative efficiencies as paper-based processes move to an electronic, automated environment. Moreover, the modernized systems offer new options to support program management. For example, states may have increased data reporting capabilities and expanded options to connect Medicaid with other systems and programs. Further, as systems and processes become more refined over time, states may be able to manage enrollment more efficiently, allowing for resources to be refocused on other activities. Looking ahead, states will continue to fully operationalize the streamlined enrollment and renewal processes outlined in the ACA and build on their developments to date to increase the use of technology, expand functionality, smooth out coordination across coverage programs, and integrate non-health programs into their new systems.

There remain key questions about how recent changes in eligibility and enrollment may be affected by a range of factors moving forward. Funding for CHIP is set to expire in 2017, raising key questions about the future of the program and what might happen in its absence. In addition, the ACA maintenance of effort provisions for children’s coverage end in 2019. State Medicaid expansion decisions will likely continue to evolve over time, and it remains to be seen how they might be affected by the gradual reduction in federal funding for newly eligible expansion adults, which begins to phase down in 2017 when it reduces to 95%. Pending proposals in current budget reconciliation legislation would roll back the Medicaid expansion to adults and eliminate the maintenance of effort requirements in 2017. Outside of these potential changes, it also will be important to examine how the Section 1115 waivers that allow states to charge adults premiums and monthly contributions are affecting coverage and program administration, particularly given that waiver authority is provided for research and demonstration purposes.

Tables

Trend and State-by-State Tables

Table 2: Waiting Period for CHIP Enrollment, January 2016

Table 3: Optional Medicaid and CHIP Coverage for Children, January 2016

Table 4: Medicaid and CHIP Coverage for Pregnant Women, January 2016

Table 6: MAGI Eligibility Systems, January 2016

Table 7: Coordination between Medicaid and Marketplace Systems, January 2016

Table 8: Online and Telephone Medicaid Applications, January 2016

Table 9: Online Account Capabilities for Medicaid, January 2016

Table 10: Income Verification Procedures Used by Medicaid Agencies at Application, January 2016

Table 12: Use of Selected Options to Facilitate Enrollment in Medicaid and CHIP, January 2016

Table 13: Renewal Processes for MAGI-Based Medicaid Groups, January 2016

Table 14: Targeted Strategies to Streamline Renewals, January 2016

Table 15: Premium, Enrollment Fee, and Cost-Sharing Requirements for Children, January 2016

Table 16: Premiums and Enrollment Fees for Children at Selected Income Levels, January 2016

Table 17: Disenrollment Policies for Non-Payment of Premiums in Children’s Coverage, January 2016

Table 20: Premium and Cost-Sharing Requirements for Section 1931 Parents, January 2016

Table 21: Premium and Cost-Sharing for Medicaid Adults, January 2016

Endnotes

Report

Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility

Iowa also used state funds to cover immigrant children in foster care.

This group of adults may include some adults with disabilities who are not eligible for Medicare.

MaryBeth Musumeci and Robin Rudowitz, The ACA and Medicaid Expansion Waivers (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, November 2015), https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-aca-and-medicaid-expansion-waivers/.

Stan Dorn and Jennifer Tolbert, The ACA’s Basic Health Program Option: Federal Requirements and State Trade-Offs (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, November 2014), https://www.kff.org/health-reform/report/the-acas-basic-health-program-option-federal-requirements-and-state-trade-offs/.

Rachel Garfield and Anthony Damico, The Coverage Gap: Uninsured Poor Adults in States that Do Not Expand Medicaid – An Update (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, October 2015), https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/the-coverage-gap-uninsured-poor-adults-in-states-that-do-not-expand-medicaid-an-update/.

Medicaid and CHIP Enrollment and Renewal Processes

80 Fed. Reg. 75817-75843 (December 4, 2015). Available at https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2015/12/04/2015-30591/medicaid-program-mechanized-claims-processing-and-information-retrieval-systems-9010.

Kevin Concannon, Kevin Counihan, Mark Greenberg and Victoria Wachino, Tri-Agency Letter on Additional Guidance to States on the OMB Circular A-87 Cost Allocation Exception, July 20, 2015. Available at http://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/SMD072015.pdf.

Vikki Wachino, CMS Letter to State Medicaid Directors and State Health Officials, SHO # 15-001; ACA #34 Re: Policy Options for Using SNAP to Determine Medicaid Eligibility and an Update on Targeted Enrollment Strategies, August 31, 2015. Available at https://www.medicaid.gov/Federal-Policy-Guidance/downloads/SHO-15-001.pdf.

Jocelyn Guyer, Tanya Schwartz, and Samantha Artiga, Fast Track to Coverage: Facilitating Enrollment of Eligible People into the Medicaid Expansion (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, November 2013), https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/fast-track-to-coverage-facilitating-enrollment-of-eligible-people-into-the-medicaid-expansion/.

“Targeted Enrollment Strategies,” CMS, accessed December 2015, http://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/program-information/targeted-enrollment-strategies/targeted-enrollment-strategies.html.

Premiums and Cost-Sharing

The Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) has indicated that the prevalent use of premiums in CHIP leads to the problem of ‘premium stacking’ for families, in which families have to pay both premiums for children enrolled in CHIP and for adults enrolled in Marketplace coverage. MACPAC notes that these combined premiums could constitute a percentage of a family’s income that is higher than the limits established by the ACA. For more information see Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, “Chapter 5: Children’s Coverage under CHIP and Exchange Plans,” in Report to the Congress on Medicaid and CHIP (Washington, DC: March 2014), 150-182, https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/2014-03-14_Macpac_Report.pdf.

On December 17, 2015, Michigan received approval for a waiver amendment. Under the approved waiver amendment, beneficiaries between 100% and 138% FPL who are not medically frail could choose between two coverage options as of April 2018: continued coverage through Medicaid managed care or the Healthy Michigan Plan or Marketplace coverage through a Qualified Health Plan (QHP) or the Marketplace Option. If beneficiaries choose Medicaid managed care, they will be required to meet a healthy behavior requirement or they could be transitioned to a QHP plan. Beneficiaries above 100% FPL would face monthly premiums of up to 2% of income in both Healthy Michigan and QHPs, but failure to pay would not result in termination of eligibility. See, Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Medicaid Expansion in Michigan (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, January 2016), https://www.kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/medicaid-expansion-in-michigan/.