Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment, and Cost Sharing Policies as of January 2019: Findings from a 50-State Survey

Medicaid and CHIP Enrollment and Renewal Processes

Enrollment and Renewal Processes as of January 2019

The ACA accelerated the adoption of data-driven enrollment and renewal processes that align and coordinate with the Marketplaces. Prior years of the survey documented that states have made significant progress upgrading or building new systems and re-engineering their business processes to provide a more modernized and streamlined enrollment and renewal experience that increasingly relies on electronic data matches to verify eligibility criteria. As noted in last year’s report, continued advancement leveled off as these systems and processes matured, although states continued to implement targeted improvements and some states are still engaged in system upgrades. This year’s data shows continued progress in some areas, plans for continued improvements, and insight into how states’ current eligibility operations compare to prior to the ACA.

Eligibility Systems and Operations

Implementation of the ACA required states to change eligibility systems to implement new MAGI-based financial eligibility methodology for pregnant women, children, parents, and expansion adults and to apply streamlined eligibility and enrollment processes for MAGI groups that coordinate with the Marketplaces. To assist states with ACA implementation and accelerate the use of technology, the federal government increased the federal match available for states to implement new or upgraded systems to 90%.

States took varied approaches to implement system changes to reflect MAGI-based Medicaid and CHIP eligibility and enrollment processes. As of January 2019, most states had launched a new eligibility system or made a significant system upgrade, while others made only necessary adjustments to existing systems. Some states implemented new systems or major upgrades when the ACA was first implemented in 2014, while others have done so more recently. Some states are still implementing new systems or upgrades, either to replace older legacy systems or to build upon and continue to improve newer systems. Tennessee, which had relied solely on the Federally-facilitated Marketplace (FFM) to implement ACA policies, launched its new combined Medicaid and CHIP eligibility system on a pilot basis in select counties in 2018, with statewide expansion planned for early 2019.

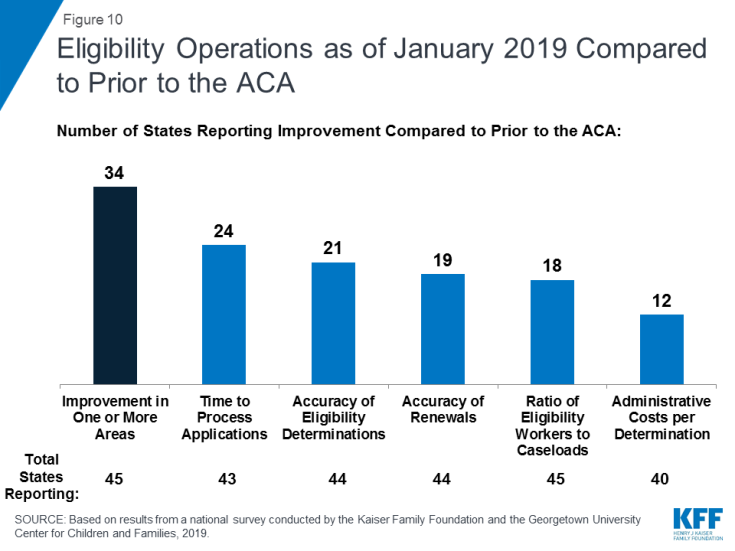

In many states, these system upgrades and re-engineered processes have contributed to improvements in eligibility and enrollment operations compared to before the ACA. Most states (34 of 46 reporting states) reported improvement in at least one area of eligibility operations compared to prior to the ACA (Figure 10). Officials in some states described how new systems provided increased efficiency and accuracy and freed up eligibility workers to work on more complex cases. Some states reported no change in their operations compared to prior to the ACA. Only six states reported that one or more of these aspects of operations were worse, but a number of those states were in the process of implementing a new system, which is often associated with short-term challenges.

Applications, Online Accounts, and Mobile Access

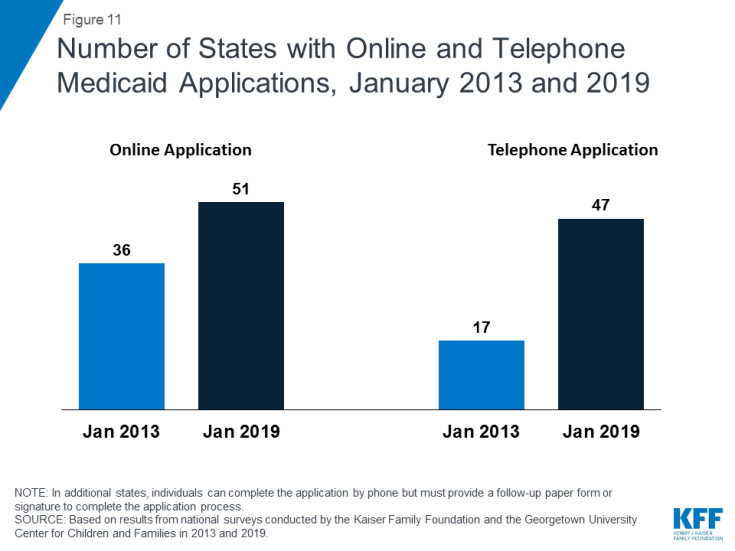

With Tennessee’s launch of a new eligibility system and accompanying web-based application in 2018, individuals can apply online for Medicaid in every state as of January 2019.1 In contrast, online applications were only available in 36 states in January 2013, the year prior to the implementation of the ACA coverage provisions (Figure 11). In 38 states, individuals can complete the online application using a mobile device, and 20 states have made the online application mobile-friendly and/or developed a mobile “app” for the application. In 2018, Indiana and Tennessee developed the capacity for individuals to apply using a mobile device, New Hampshire and Nevada added a mobile-friendly design to their application, and Wisconsin launched a mobile “app” for its online application. Additional states plan to enhance mobile functionality in 2019 or later. All states also offer the ability for individuals to apply via telephone, but four states have not enabled telephonic signatures and require a follow-up paper form or electronic signature to complete the application. The broad availability of telephone applications also represents a significant increase compared to prior to the ACA, when telephone applications were accepted in only 17 states.

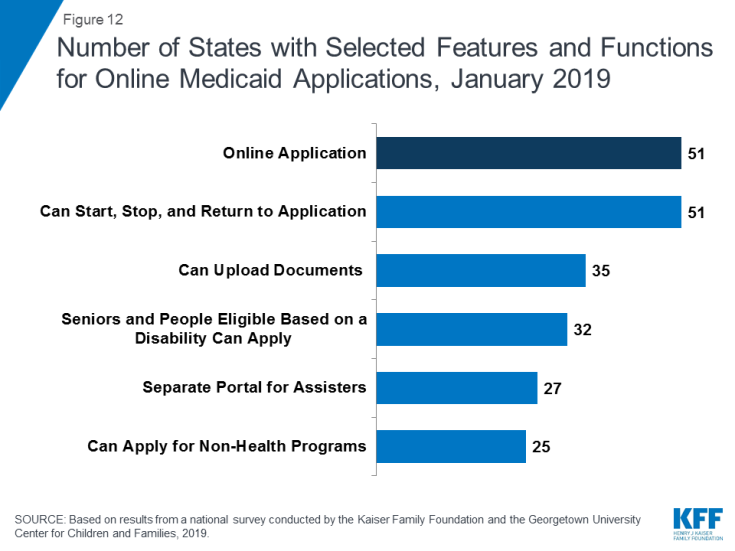

All states have designed their online applications so that individuals may start, stop, and return to the application (Figure 12). In addition, two-thirds of states (35) provide the option for individuals to scan and upload documents that may be needed to verify eligibility, and 27 states have separate portals for application assisters to submit facilitated applications. In 32 states, all Medicaid eligibility groups (children, pregnant women, adults, seniors, and individuals eligible based on a disability) can apply through a combined online application. Half of the states (25) offer a multi-benefit online application that also allows individuals to apply for at least one non-health program such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), or child care assistance. These combined applications can facilitate individuals’ access to a broader array of services, but also may increase the length and complexity of the application.

Figure 12: Number of States with Selected Features and Functions for Online Medicaid Applications, January 2019

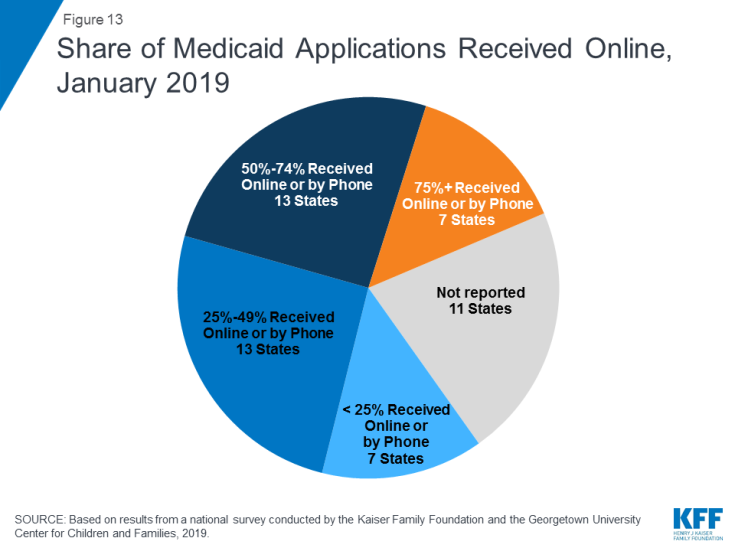

Although online applications offer potential benefits to individuals and states, other application pathways remain important. Online applications can make applying for coverage more convenient and accessible for some individuals, and can facilitate faster processing of determinations, limit data entry errors, and reduce state administrative burdens. However, other application pathways remain important for individuals who may not have easy access to a computer or the internet or who feel more comfortable applying in-person or through a paper form. Among the 40 states able to report data on modes of application, the median share of applications received online was 50%. The remaining half came via phone, in-person, or mail, although the share of telephone applications was very small in many states. Of these 40 states, 20 reported receiving half or more of applications online, including 7 states that reported receiving at least 75% of applications online (Figure 13). However, the share varied widely across states, ranging from 4% in Mississippi to 90% or higher in Florida, New York and Texas.

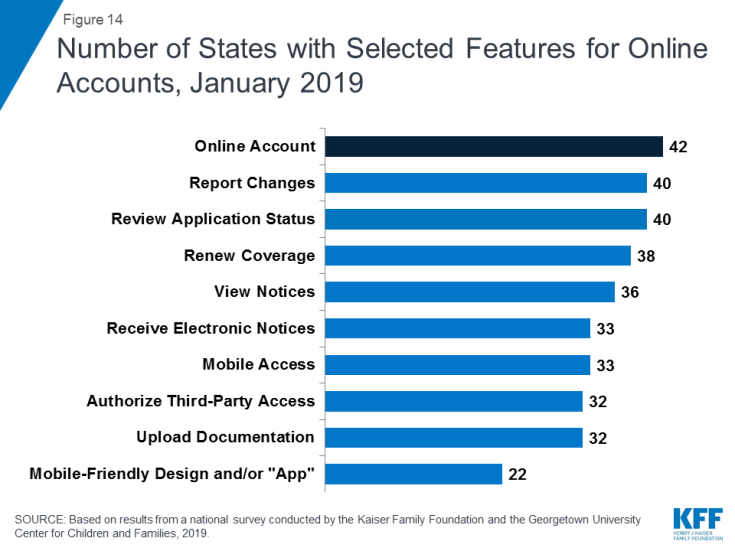

States continued to advance the use of electronic accounts for enrollees to review or submit information. Online accounts add convenience for enrollees to access and update their information and efficiencies for states by eliminating the need for caseworkers to manually enter information like address changes. With New Jersey and Tennessee implementing electronic accounts, 42 states provided electronic accounts as of January 2019. During 2018, states also continued to expand the functions and features of existing accounts. As of January 2019, most states offer a broad array of functions through their accounts (Figure 14). In 33 of the 42 states with an electronic account, enrollees can access the account through a mobile device. Additionally, 21 states indicate that the online account has been designed with mobile-friendly formatting and six report that they have created a mobile “app” through which individuals can access their account. Several states reported plans to enhance mobile access to online accounts during or after 2019.

Eligibility Determinations

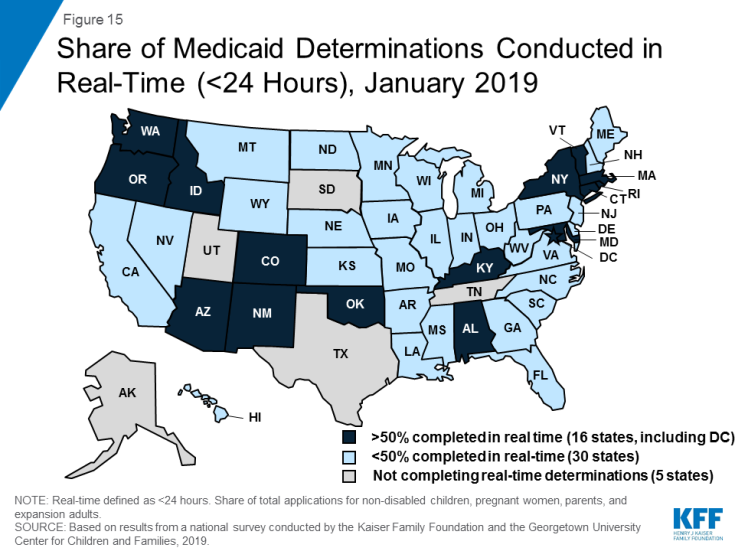

With new or upgraded eligibility systems, states are increasingly able to make real-time eligibility determinations (within 24 hours) by using electronic data matches to verify eligibility criteria. As of January 2019, 46 states are able to make real-time eligibility determinations. However, the share of determinations completed in real-time varies widely across states. A total of 16 states report conducting at least half of MAGI-based determinations in real-time, including 9 states which make three-quarters or more of determinations in under 24 hours (Figure 15). States processing the majority of their applications in real-time are more likely to report that most are made by the eligibility system automatically without caseworker action, while those processing a lower share in real-time are more likely to require caseworker interaction to complete the determination. Automated determinations are more efficient and can reduce data entry errors and administrative burden, but systems and links to trusted data sources must be well-tested and subject to ongoing quality assurance to ensure accuracy.

The majority of states do not report any problems or delays in their eligibility determinations. However, ten states indicated problems or delays as of January 2019. About half of these states are continuing to make changes to systems and processes, which may be contributing to these challenges. Other reasons for backlogs include gaps in staffing and resources or increased volume of applications resulting from recent implementation of the Medicaid expansion.

All states verify citizenship or qualified immigration status, as well as income, when determining eligibility for Medicaid and CHIP. States are able to electronically verify citizenship or immigration status either directly with the Social Security Administration or Department of Homeland Security or through the federal data services hub that consolidates access to these sources. These verifications must be conducted prior to determining eligibility, however, individuals who attest to a qualified status must be given a reasonable amount of time to provide documentation if eligibility cannot be confirmed electronically. While states must also verify income, they have the option to do so prior to enrollment, which 45 states do, or to enroll based on the applicant’s reported income and verify post-enrollment. Verification policies for other eligibility criteria, including age/date of birth, state residency, and household size, vary across states, reflecting state options to verify this information before or after enrollment or to accept the individual’s self-attestation.

Just over half of states (28) report that they conduct data matches on a periodic basis to identify changes in circumstances between annual redetermination periods. States may disenroll individuals if these data checks reveal changes in income or other information that affect eligibility and the individual is unable to resolve the discrepancy within specified timeframes (often within ten days from the date of the notice). These data checks can lead to coverage losses among eligible individuals if they do not receive the notice or are not able to provide documentation within the required timeframe. States vary in the frequency of these checks. For example, some conduct them quarterly, while others conduct only one check between annual renewals. In 2018, Minnesota and Tennessee implemented routine data checks to verify eligibility. Several additional states have recently passed legislation or are considering legislation to require stricter and more frequent data checks.2,3

The need for presumptive eligibility has decreased as states are increasingly able to process determinations quickly, but it remains an avenue in some states for people to access temporary coverage when they are unable to receive a real-time determination. Presumptive eligibility is a long-standing policy option that allows states to train and authorize qualified entities such as federally qualified health centers or prenatal clinics to make a temporary eligibility determination so that individuals can quickly access temporary coverage while their final eligibility determination is processed. The ACA expanded the use of presumptive eligibility to allow hospitals in all states to presumptively enroll MAGI-based groups including parents and expansion adults, although Arkansas obtained an exemption from this requirement through a Section 1115 waiver. As of January 2019, 30 states use presumptive eligibility for pregnant women and 20 states have adopted the policy for children. Fifteen states also have extended the policy to parents, adults, family planning services, and/or former foster youth.

System Integration

States continue to reintegrate Medicaid eligibility determinations for seniors, individuals eligible based on a disability, and non-health programs into their upgraded Medicaid systems. Prior to the ACA, state systems generally determined eligibility for all Medicaid groups and most included non-health programs, such as TANF and SNAP.4 The ACA required states to use new financial eligibility rules and streamlined enrollment policies for MAGI-based groups. However, states continue to apply their pre-ACA financial eligibility rules to non-MAGI groups (seniors and individuals eligible based on a disability). As a result, some states separated MAGI eligibility determinations from non-MAGI groups and non-health programs when they implemented the ACA. As their new systems have matured, states have increasingly reintegrated non-MAGI groups and non-health programs into the upgraded systems. This trend continued in 2018, with Iowa and Tennessee integrating non-MAGI groups into their systems. As of January 2019, 32 states determine eligibility for all Medicaid groups through a single system, and, in 24 states, the MAGI-based Medicaid eligibility system determines eligibility for at least one non-health program. This integration can facilitate access to services for individuals and offer efficiencies to states but requires more complex system implementation. States also have realized progress integrating Medicaid and CHIP eligibility determinations. Prior to the ACA, less than half of states with separate CHIP programs (16 of 38) used a single system for Medicaid and CHIP, but, as of January 2019, all but 1 of the 36 states with separate CHIP programs determine eligibility through a single system. Looking ahead, states remain focused on reintegration with nearly half indicating plans to integrate non-MAGI groups and/or additional non-health programs into their MAGI-based system in 2019 or beyond.

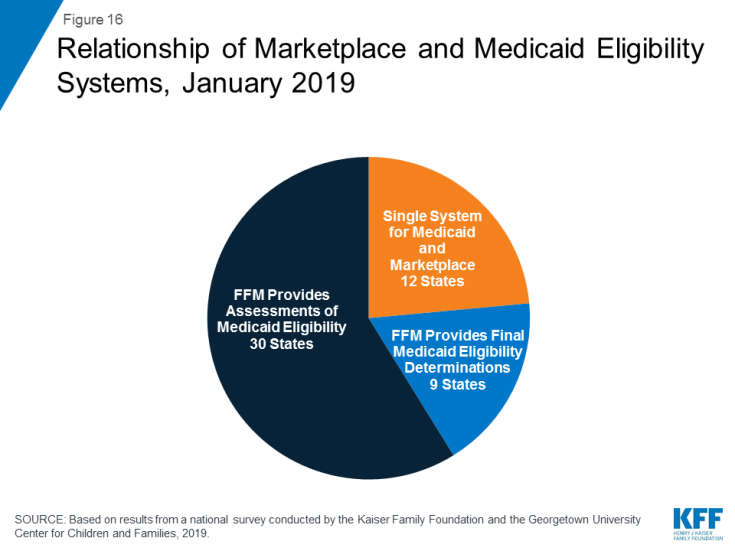

All states coordinate Medicaid and Marketplace coverage, as required under the ACA. However, how states coordinate this coverage depends on the structure of its Marketplace. Most states (39) rely on the Federally Facilitated Marketplace (FFM) system, known as Healthcare.gov, for Marketplace eligibility determinations and enrollment. These states must electronically transfer data back and forth with the FFM to coordinate Medicaid and Marketplace coverage. States report that these transfers generally are going smoothly without any significant delays or problems. Of the 39 states relying on the FFM platform, 30 states use the FFM only to assess Medicaid eligibility, and then make a final determination after the case is transferred to the state. In 2018, Arkansas shifted to receiving assessments from the FFM. Nine states allow the FFM to make final Medicaid or CHIP determinations, including Virginia, which switched from an assessment to a determination state in 2018 to facilitate its implementation of the Medicaid adult expansion. In the remaining 12 states that use their own State-based Marketplace system, Medicaid, CHIP, and Marketplace determinations are conducted through a single integrated system (Figure 16).

Renewals

Streamlined renewal policies can facilitate continuous coverage among eligible individuals, which helps prevent gaps in care and protects individuals from medical costs that might occur if they experience breaks in coverage. Under ACA policies, states are required to use available data to determine ongoing eligibility before requesting the enrollee to complete a renewal form or provide documentation. If a state is unable to determine ongoing eligibility based on available data, it may then request additional information from the individual and must provide the individual multiple avenues to renew, including online, by phone, in-person, or via mail. The move to automatic renewals can help reduce “churn” or short gaps in coverage, contribute to efficiencies and cost savings, and reduce data entry errors and administrative burden. However, eligible individuals may remain at risk for losing coverage at renewal if the state is unable to determine ongoing eligibility based on available data and they do not receive or understand notices or forms requesting additional information and respond to requests within required timeframes, which are often limited to 10 days.

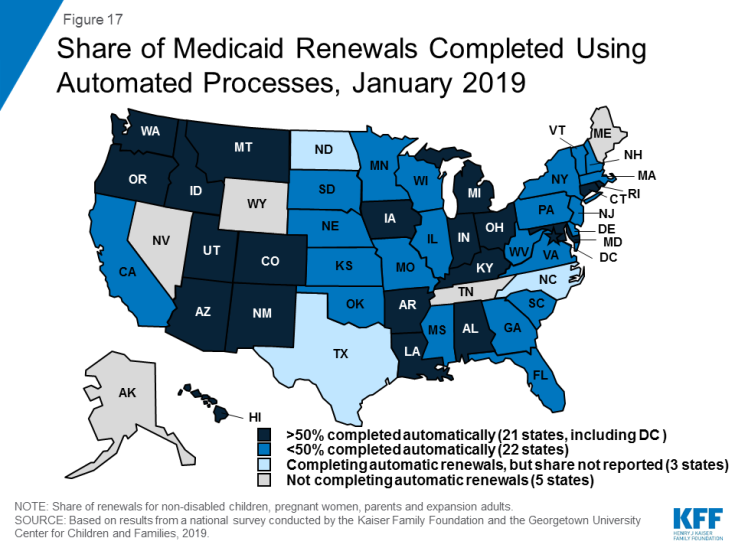

As of January 2019, 46 states were completing automatic or “ex parte” renewals, through which the state renews coverage based on available eligibility-related data. Among the 43 states able to report the share of renewals completed through automated processes, 21 states reported at least half of MAGI renewals are conducted automatically, including 10 states that complete three-quarters or more of renewals automatically (Figure 17). States with a high share of automatic renewals are more likely to have a system that can complete the renewals without requiring caseworker action. Conversely, states that rely on manual action by a caseworker—for example, to look up data to verify ongoing eligibility—generally report a smaller share of renewals completed automatically.

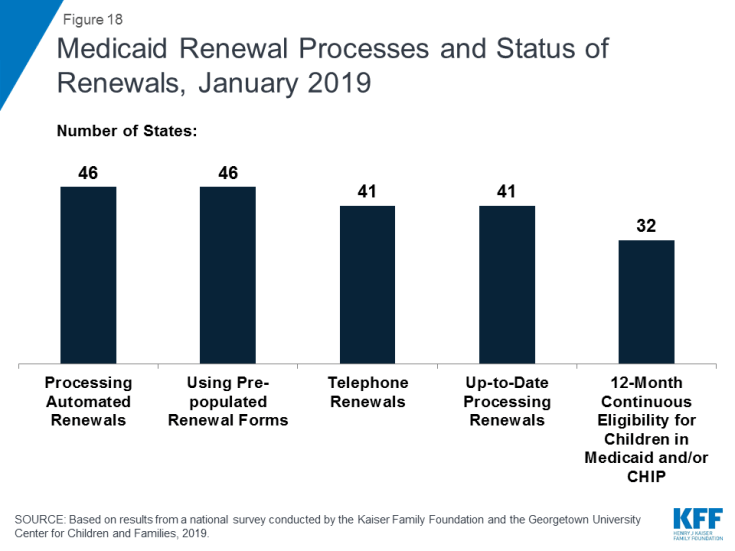

When unable to renew coverage based on available data, 46 states send pre-populated forms to enrollees to facilitate the renewal process (Figure 18). This count includes Tennessee and Vermont which began sending pre-populated forms in 2018. Idaho stopped mailing pre-populated forms in 2018, and like Florida and Oklahoma, sends a notice to the individual requesting that they log into their online account or call to confirm their information and/or report any changes. Most states (41), allow individuals to renew by phone; and four additional states allow individuals to complete most of the renewal process by phone, but still require a paper form or electronic signature to complete the process.

As of January 2019, the majority of states were up-to-date in processing Medicaid and CHIP renewals. However, ten states reported delays with most of these states overlapping with the ten states that reported delays in application processing. Causes of renewal delays were similar to those contributing to backlogs in eligibility determinations, including issues related to system upgrades or challenges related to staffing and volume of renewals.

Nearly two-thirds of the states (32) minimize gaps in coverage for children by providing 12-month continuous eligibility in either Medicaid and/or CHIP. All states are required to renew coverage every 12 months for children, pregnant women, parents and expansion adults. However, during that 12-month period, individuals may lose coverage if they experience a change in circumstance that makes them ineligible, such as an increase in income. For children, states can opt to provide 12-month continuous eligibility, which allows a child to remain enrolled for a full year unless the child ages out of coverage, moves out of state, voluntarily withdraws, or does not make required premium payments. Continuous eligibility promotes stable access to care by reducing “churn” or individuals moving on and off coverage due to modest, and often temporary, changes in circumstances such as overtime or extra seasonal work. Continuous eligibility also facilitates a more accurate assessment of the quality of health care children receive in Medicaid and CHIP because most quality measures require minimum periods of enrollment. As of January 2019, 24 states have adopted continuous eligibility for children in Medicaid and CHIP, and eight additional states have implemented the policy only in their separate CHIP programs. Montana and New York also provide 12-month continuous coverage for adults through a Section 1115 waiver.