Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment, and Cost Sharing Policies as of January 2019: Findings from a 50-State Survey

Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility

Eligibility as of January 2019

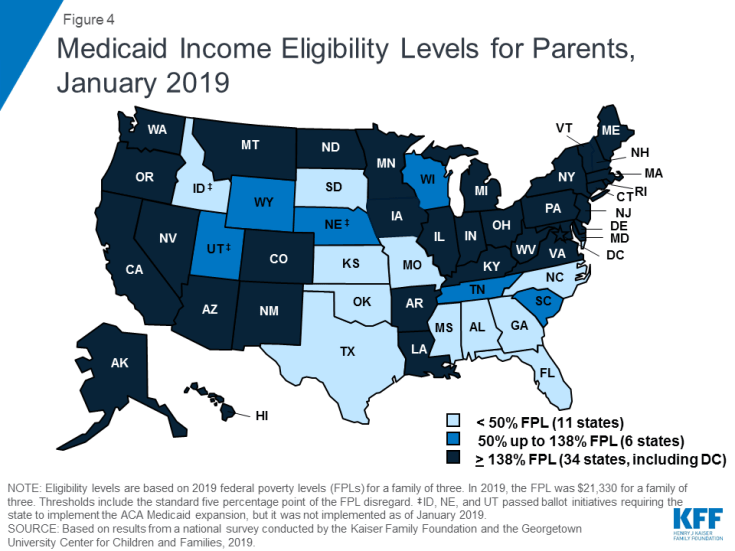

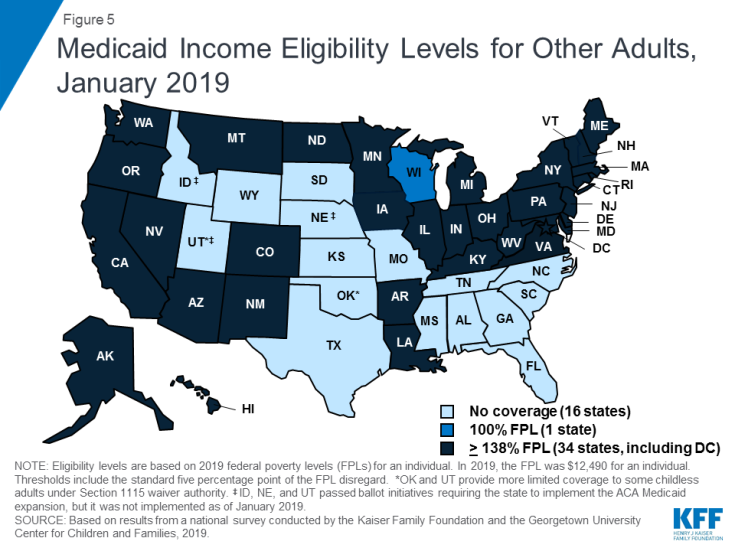

Under the ACA, most states have expanded Medicaid to low-income adults. As of January 2019, 34 states, including DC, had implemented the Medicaid expansion, extending eligibility to parents and other adults with incomes up to 138% FPL ($29,435 for a family of three or $17,236 for an individual as of 2019) (Figures 4 and 5). Connecticut and DC provide eligibility to higher levels. DC covers parents to 221% FPL and other adults to 215% FPL, and Connecticut restored parent eligibility to 155% FPL in 2018, after it had been reduced to 138% FPL in 2017.

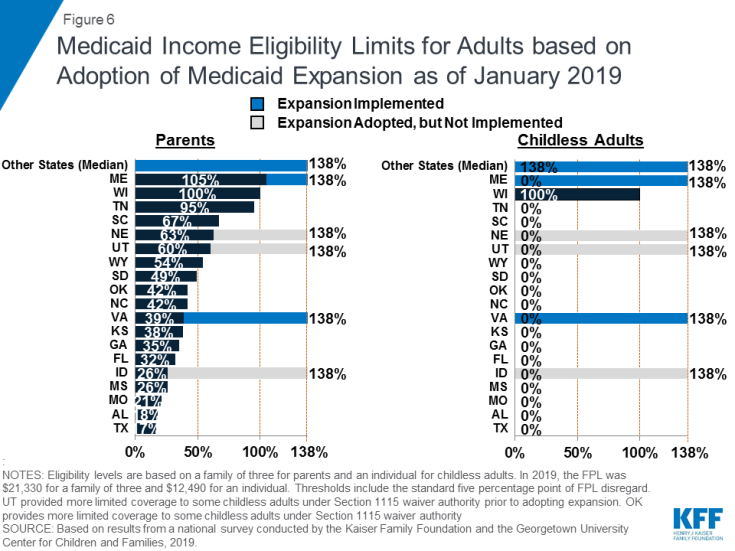

There was an uptick in state action to expand in the past year, with five additional states taking steps forward. In January 2019, Maine and Virginia implemented the Medicaid expansion, significantly increasing eligibility for parents and other adults (Figure 6). Through ballot initiatives in November 2018, Idaho, Nebraska, and Utah voters adopted the expansion, although it had not yet been implemented as of January 2019, and Utah and Idaho are seeking to add restrictions to their expansions. With this state action, 37 states, including DC, had adopted the expansion as of January 2019.

Figure 6: Medicaid Income Eligibility Limits for Adults based on Adoption of Medicaid Expansion as of January 2019

In the 14 states that have not yet adopted or implemented the Medicaid expansion, eligibility levels remain limited to very low-income parents, and other adults are largely ineligible. In these states, the median eligibility level for parents was 40% FPL, or $8,532 for a family of three, with ten states limiting parent eligibility to less than half of the poverty level. Other adults remain ineligible for Medicaid regardless of their income in all of these states, except Wisconsin. Moreover, in 10 of these 14 states, the parent eligibility level has been eroding over time as a percent of the FPL (from 42% FPL to 39% FPL between January 2014 and January 2019), because it is tied to a static dollar threshold, while the FPL generally increases each year. This erosion further widens the disparity in coverage available for adults in expansion states versus those that have not yet adopted the expansion.

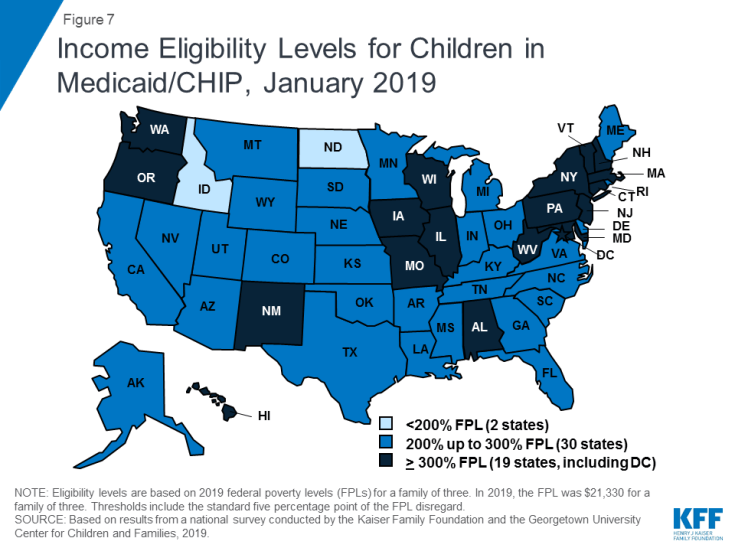

As of January 2019, eligibility levels for children were robust, with 49 states covering children with incomes above 200% FPL (Figure 7). Eligibility levels for children ranged from 175% FPL to 405% FPL across states, with a median level of 255% FPL. All states use CHIP funding to extend children’s coverage through a Medicaid expansion, a separate CHIP program, or a combination of both approaches. As of January 2019, 36 states had a separate CHIP program, which provides states additional flexibility with regard to benefits, premiums, and cost sharing. However, 16 of these states provide children in their separate CHIP program the full Early, Periodic, Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment Services (EPSDT) benefit that is the Medicaid benefit standard for children.

In 2018, Congress extended CHIP funding through 2027, which supports stable coverage for children. This action followed the longest funding lapse since the CHIP program was enacted in 1997, which had put continued coverage in jeopardy. The legislation retained the MOE provision requiring states to preserve children’s eligibility levels and enrollment policies. Starting in October 2019, however, the MOE will not apply to eligibility levels above 300% FPL.1 At that time, states may continue covering children at these higher income levels and receive federal funding, but they would newly have the option to reduce eligibility to 300% FPL. This change in the MOE coincides with the beginning of a phase-out of the 23-percentage point temporary boost in federal CHIP matching rates. Also in 2018, Congress passed legislation requiring states to cover all former foster youth up to age 26 in Medicaid, regardless of where the youth was in foster care.2 Previously, states were only required to cover those who had been in foster care within the state. This provision will become effective in 2023. In the interim, as of January 2019, 11 states have a waiver to cover former foster children regardless of whether they had been in care within the state, with Michigan discontinuing this coverage in 2018.

Almost half of states (22) report using CHIP funds to support a Health Services Initiative (HSI). Since the enactment of CHIP in 1997, states have had an option to utilize CHIP funds to support a state-designed HSI to improve the health of low-income children, as long as CHIP administrative costs combined with HSI services do not exceed 10% of total CHIP expenditures. HSIs must directly improve the health of low-income children who are eligible for CHIP and/or Medicaid but may serve children regardless of income. States reported a variety of purposes for their HSIs with the most common including supporting poison control systems, enhancing access to health services in schools, providing immunization services, and funding lead abatement efforts. Several states have enacted multiple initiatives through HSI funding with unique purposes ranging from supporting early reading programs in Oklahoma to providing respite care for children with developmental disabilities in New Jersey.

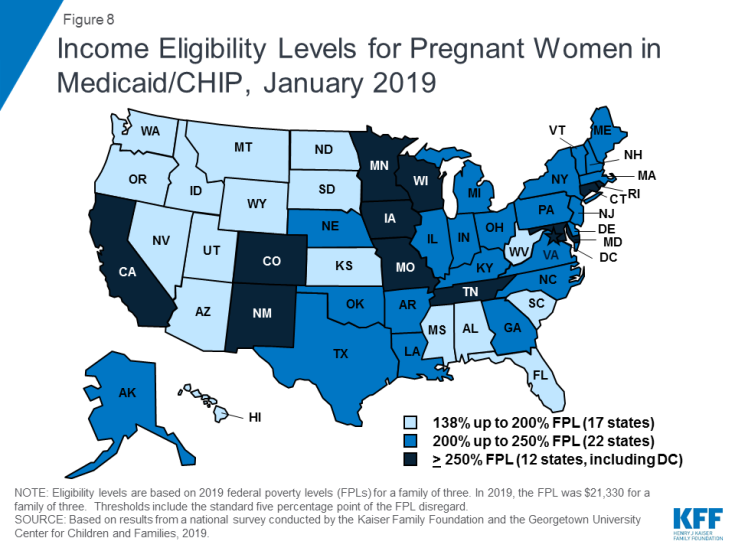

The median eligibility level for pregnant women remained steady at 200% FPL, with the upper eligibility limit ranging from 138% FPL to 380% FPL across states. The majority of states (47) provide Medicaid eligibility to pregnant women beyond the federal minimum of 138% FPL, and nearly half of states (22) extend eligibility to above 200% FPL (Figure 8). Five states use CHIP funds to cover pregnant women above Medicaid levels. In 46 states, pregnant women receive full Medicaid benefits (versus pregnancy-related services only), and all five states covering pregnant women with CHIP funds provide full CHIP benefits. All states are required to provide family planning services to individuals in Medicaid, while 28 states offer family planning services to individuals not otherwise eligible for Medicaid through a state option or waiver.3 In 2018, Maryland expanded family planning eligibility to 264% FPL to match its eligibility level for pregnant women and extended eligibility to men while New Mexico added age restrictions to its coverage.

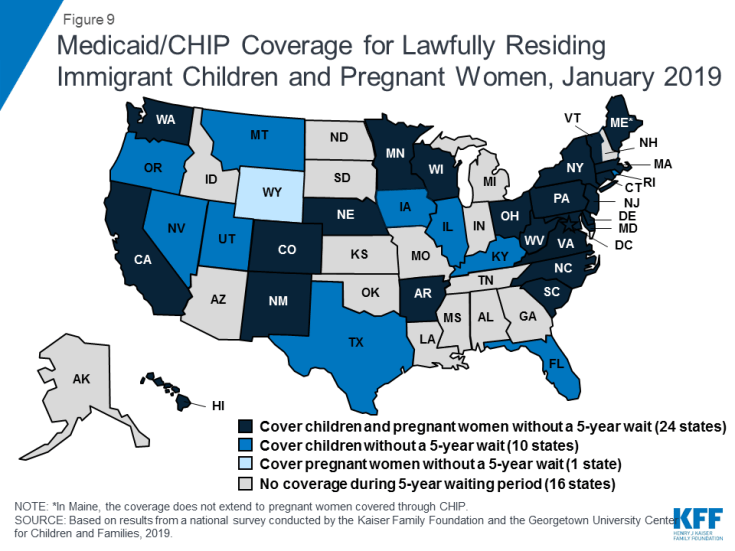

A total of 35 states have taken up the option to eliminate the five-year waiting period for Medicaid/CHIP coverage for lawfully-residing immigrant children and/or pregnant women (Figure 9). Lawfully residing immigrants may qualify for Medicaid and CHIP but are subject to eligibility restrictions. In general, they must have a “qualified” immigration status and many, including most lawful permanent residents or “green card” holders, must wait five years after obtaining qualified status before they may enroll.4 States have an option to eliminate the five-year wait for lawfully residing immigrant children and pregnant women.5 Half of states (24) apply the option to both children and pregnant women, while ten states use it for children only, and one state (Wyoming) uses it only for pregnant women. This count includes Nevada, which implemented the option for children in January 2019. Since 2002, states also have had the option to provide prenatal care to women regardless of immigration status by extending CHIP coverage to the unborn child, which 16 states provided as of January 2019. Undocumented immigrants are not eligible to enroll in Medicaid or CHIP, but some states have fully state-funded programs that cover certain groups of immigrants regardless of immigration status, including seven states that cover all income-eligible children.6

Figure 9: Medicaid/CHIP Coverage for Lawfully Residing Immigrant Children and Pregnant Women, January 2019

Emerging Eligibility Restrictions in Section 1115 Waivers

In 2018, some states obtained Section 1115 waivers to add eligibility requirements to their Medicaid programs not otherwise allowed under federal rules. Many of these provisions are targeted to low-income adults made eligible by the ACA Medicaid expansion, although, in some states, they also affect poor parents and other traditional groups that existed prior to the ACA.7,8As of January 2019, 13 states had approved waivers that allow one or more eligibility requirements, including conditioning eligibility on meeting a work requirement, adding completion of a health risk assessment as an eligibility requirement, charging premiums or monthly contributions, eliminating retroactive eligibility, delaying coverage until the first premium payment, and/or locking enrollees out of coverage for a period of time if they have unpaid premiums or do not complete timely renewals or report changes in circumstances.9 However, many of these provisions had not yet been implemented as of January 2019.

These new eligibility requirements will increase barriers to coverage and contribute to coverage losses.10,11 Under these new requirements, eligible people may lose coverage due to their inability to navigate more complicated enrollment processes and requirements, such as documenting work or a qualifying exemption.12 Moreover, a large and longstanding body of research shows that premiums serve as an enrollment barrier among the low-income population.13 As such, implementation of the eligibility restrictions will likely lead to reductions in Medicaid enrollment and erode coverage gains achieved under the ACA. For example, in Arkansas, the first state to implement a work requirement under a waiver, over 18,000 individuals lost coverage between September and December 2018 due to not meeting the work reporting requirements.14 Additional research is needed to understand more about enrollees who lost coverage, but an early study found that many enrollees in Arkansas were unaware of or confused by the new requirements (despite outreach efforts) and faced multiple barriers complying with the work and reporting requirements that initially could only be reported online.15

Recent waiver provisions also would make enrollment processes more complex and increase administrative burdens on states.16 Implementing these types of eligibility provisions increases documentation requirements on individuals and states and can be administratively complex and costly. A number of states reported that implementing or preparing to implement these waivers increased administrative costs, staff time, the length of time to process renewals, and/or required changes to systems. For example, states implementing work requirements likely have to make system changes to reflect new eligibility rules; document compliance with new requirements; interface with other programs; implement coverage lockout periods; and exchange information among the state, enrollment broker, health plans, and providers. Additional staff may be required to educate enrollees, develop notices, evaluate and process exemptions, and review applications as churn increases and enrollees reapply or appeal coverage lockout periods.