Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility and Enrollment Policies as of January 2021: Findings from a 50-State Survey

Introduction

Since its emergence a year ago, the coronavirus has had implications for the health of the nation and our economy, exposing gaps in the public health infrastructure and further highlighting the importance of health coverage. During this time, enrollment in Medicaid has increased as people sought coverage after losing jobs or income because of the pandemic. Through the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act (CARES), states are required to maintain eligibility standards and provide continuous enrollment in Medicaid until the end of the public health emergency (PHE) in order to qualify for a 6.2 percentage point increase in Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP). The continuous coverage provision, along with new applications, resulted in Medicaid enrollment growth of 6.7% between February and September 2020 (the most recently available data). States were also able to adopt a range of options through temporary changes in their state Medicaid plans (SPAs),through disaster-related waivers, and through other administrative authorities to streamline processes and connect individuals to coverage more quickly, such as expanding use of presumptive eligibility and allowing self-attestation of certain eligibility criteria.

This 19th annual survey of the 50 states and the District of Columbia (DC), provides data on state Medicaid and CHIP eligibility levels and presents a snapshot of key aspects of state enrollment and renewal procedures in place during the COVID-19 public health emergency. In light of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the survey was scaled back in length and scope and focuses on state actions taken or planned in response to the pandemic. The report is based on a survey of state Medicaid and CHIP program officials conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) and the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families during January 2021. The report includes policies for children, pregnant women, parents and other non-elderly adults whose eligibility is based on Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) financial eligibility rules; it does not include policies for groups eligible through Medicaid pathways for adults over the age of 65 or on the basis of disability.

Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility

As of January 2021, Medicaid and CHIP eligibility is largely unchanged from 2020 due to maintenance of eligibility (MOE) requirements tied to enhanced federal funding. To help support states and promote stability of coverage amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, the FFCRA provides a 6.2 percentage point increase in the federal share (FMAP) of certain Medicaid spending if states meet certain MOE requirements. The MOE provisions prohibit states from tightening eligibility and enrollment standards beyond policies in place as of January 1, 2020 and require states to provide continuous coverage and to cover COVID-19 testing and treatment for Medicaid enrollees. The MOE continuous coverage requirement remains in place until the end of the month when the public health emergency (PHE) expires or is terminated. The MOE does not apply to CHIP programs, but other MOE requirements remain in place for CHIP.1 While states continue to have the flexibility to increase eligibility or implement new enrollment and renewal processes, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the economic recession have limited states’ ability to do so, resulting in few changes in eligibility outside of temporary emergency authorities.

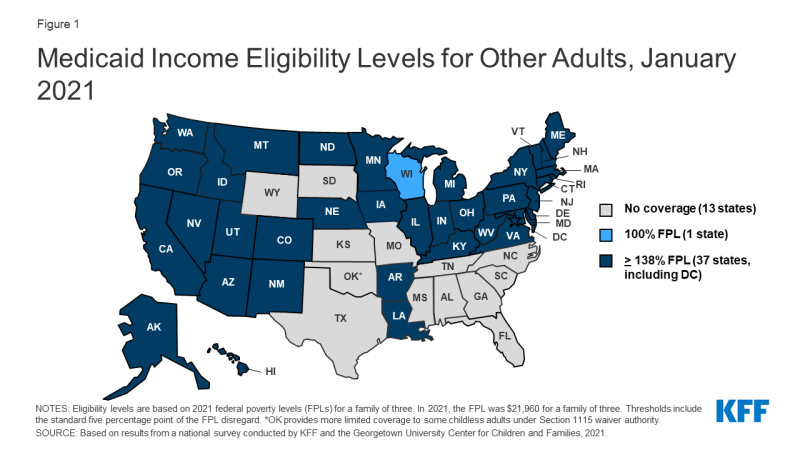

In October 2020, Nebraska implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion, the only major eligibility policy change in 2020. As of January 2021, 37 states extend coverage to adults without dependent children with incomes up to 138% FPL ($30,305 for a family of 3) (Figure 1). Also, in 2020, Missouri and Oklahoma voters approved ballot initiatives to implement Medicaid expansion in their states. When Medicaid expansion was first launched in January 2014, 26 states (including DC), participated. Since then, an additional 13 states have adopted the Medicaid expansion, six via state ballot initiatives. Following implementation in Missouri and Oklahoma, planned for mid-2021, the total number of expansion states will increase to 39.

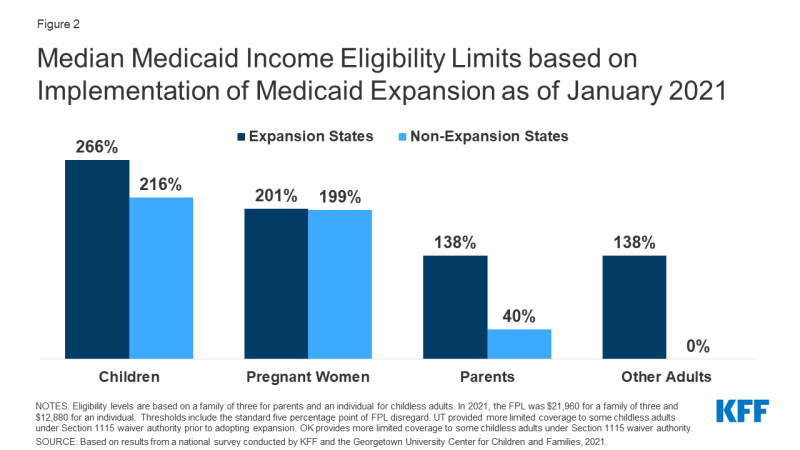

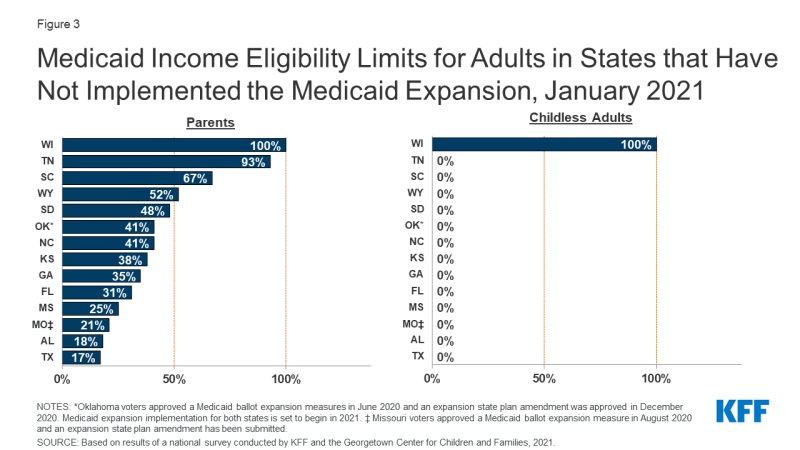

In states that have not implemented the Medicaid expansion, eligibility for parents and other adults remains extremely low (Figures 2 and 3). The median eligibility level for parents and caretakers in the 14 non-expansion states remains at 40% FPL ($8,784 annually for a family of three), ranging from a low of 17% FPL in Texas to 100% FPL in Wisconsin. Ten non-expansion states base eligibility on a fixed dollar threshold that is converted to the equivalent federal poverty level for comparison purposes. Over time, the equivalent eligibility level will decrease when annual updates adjust federal poverty levels upward to account for inflation. Wisconsin remains the only non-expansion state to cover adults without dependent children, extending eligibility up to 100% FPL for these adults through a waiver.

Figure 2: Median Medicaid Income Eligibility Limits based on Implementation of Medicaid Expansion as of January 2021

Figure 3: Medicaid Income Eligibility Limits for Adults in States that Have Not Implemented the Medicaid Expansion, January 2021

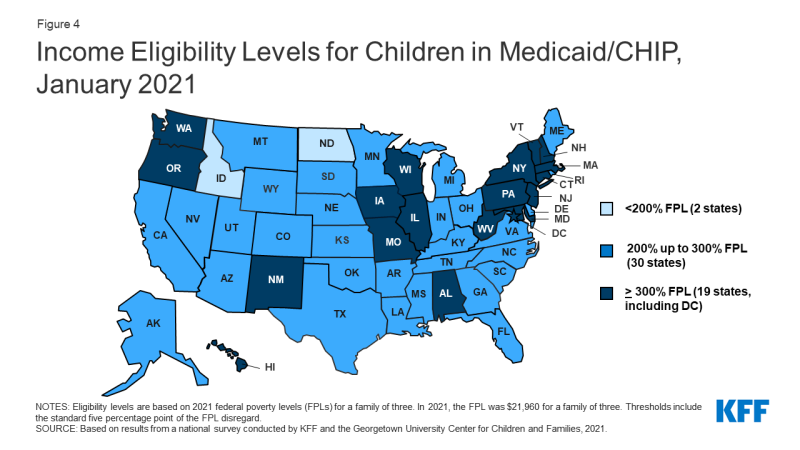

Children’s upper income eligibility in Medicaid and CHIP continues to be the highest of all eligibility groups with 49 states covering children at or above 200% FPL (Figure 4). In 2020, the median eligibility level for children held steady at 255% FPL, ranging from a low of 175% FPL in North Dakota to a high of 405% FPL in New York. More than a third of the states (19) cover children at or above 300% FPL. The only change in eligibility levels for children’s coverage was in Kansas, where CHIP eligibility is linked to a dollar-based income level tied to the 2008 FPL. While the dollar value remains the same, over time, the equivalent eligibility level will decrease when the federal poverty level is adjusted upward to account for inflation.

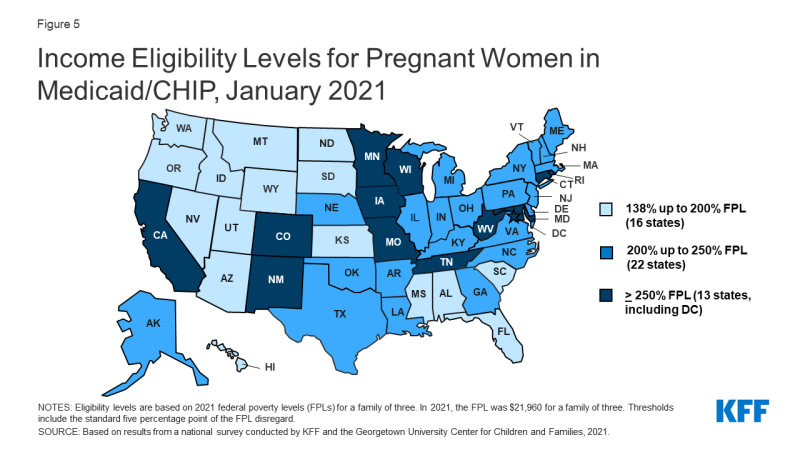

The median eligibility limit for coverage for pregnant women in Medicaid and CHIP is stable at 205% FPL (Figure 5). Across states, eligibility levels for pregnant women in Medicaid and CHIP range from a low of 138% FPL (the federal minimum level) in Idaho and South Dakota to a high of 380% FPL in Iowa. A total of 35 states cover pregnant women at or above 200% FPL. Six states have expanded coverage for pregnant women through CHIP, an option for states that cover pregnant women in Medicaid up to at least 185% FPL.

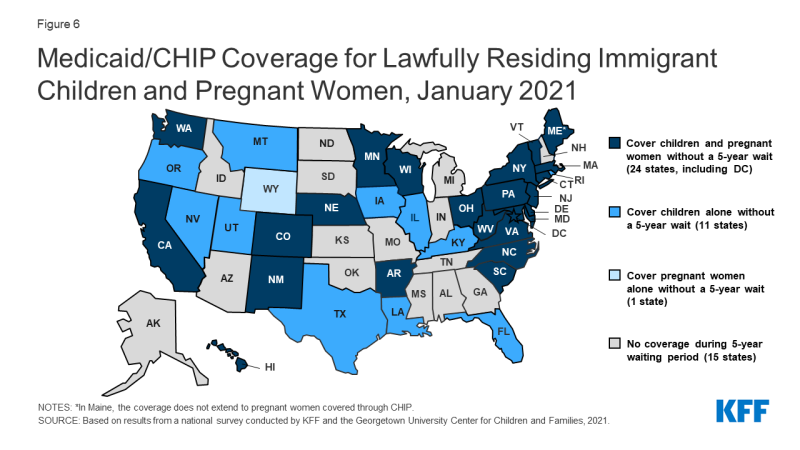

As of January 2021, 41 states have adopted federal options or use state-only funds to extend coverage or limited benefits to some immigrant children, pregnant women, or non-elderly adults. CHIP’s enactment in 1997 included the unborn child option that allows states to provide coverage from conception to birth, thereby extending coverage to pregnant women regardless of immigration status. A total of 17 states have adopted this option. Then, the 2009 CHIP Reauthorization Act (CHIPRA) offered a new option for states to receive federal funding to cover lawfully-residing children and pregnant women in Medicaid and CHIP without the five-year waiting period. Since then, two-thirds of states (35) have implemented the option for children in Medicaid and all of those states with separate CHIP programs (24 states) cover lawfully-residing children in CHIP (Figure 6). Twenty-five states have adopted the CHIPRA option to cover lawfully-residing pregnant women. Additionally, eight states use state-funds to cover children who are ineligible for federal funding due to immigration status, five states provide pre-natal or postpartum services to some immigrant pregnant women, and eight states cover other immigrant adults.

Figure 6: Medicaid/CHIP Coverage for Lawfully Residing Immigrant Children and Pregnant Women, January 2021

The median eligibility level for family planning services is 206% FPL, but eligibility levels range from 138% FPL in Louisiana and Oklahoma to a high of 306% FPL in Wisconsin. In 2020, Texas became the 30th state to provide family planning services using federal funds. Texas offers family planning services through a Section 1115 demonstration waiver, Healthy Texas Women, which includes restrictions on free choice of family planning providers.

Enrollment and Renewal Processes During the PHE

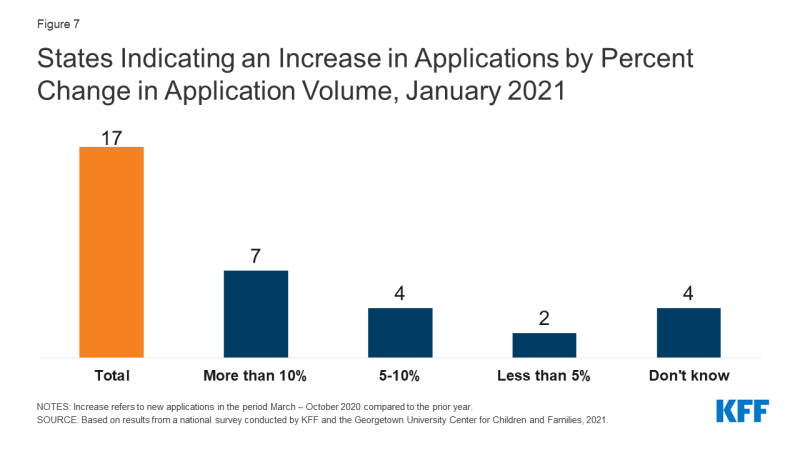

One third of states have experienced an increase in new applications since the beginning of the COVID-19 PHE (Figure 7) and few states reported application backlogs. Seventeen states report that the volume of new applications increased during the COVID-19 PHE compared to the same period in 2019. Seven of these states (Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, Nebraska, New York, Nevada, and Tennessee) report increases of greater than 10%. Despite overall Medicaid enrollment growth, states may not be experiencing large increases in applications for a variety of reasons, including smaller than expected declines in employer-sponsored insurance, a drop in applications early in the pandemic due to office closures and the elimination of reapplications (where an individual loses coverage, often due to procedural reasons, then reapplies a short time later) due to the MOE requirements. Only five states report current delays in processing new applications beyond the current timeliness standards. Two of the five states with backlogs indicated their current backlogs were lower than in the prior year, while one state indicated that the backlog was the result of decreased administrative capacity due to the pandemic. CMS expects that states will resume timely processing of all applications within four months of the end of the PHE. Since most states are not currently experiencing application backlogs, they can potentially focus resources on processing renewals or changes in circumstances before the end of the PHE.

Figure 7: States Indicating an Increase in Applications by Percent Change in Application Volume, January 2021

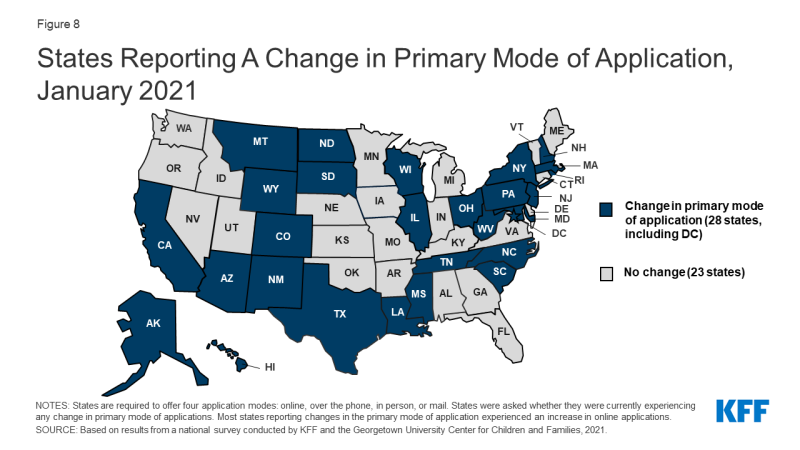

Just over half of states (28) report a shift in how individuals are applying for Medicaid coverage, largely driven by an increase in online applications (Figure 8). The ACA required states to create a single streamlined application for Medicaid, CHIP, and Marketplace coverage and to provide options for individuals to apply for and renew coverage through multiple modes, including online and phone. Most states reporting a change in the primary mode of application experienced an increase in online applications, likely driven by limited access to in-person application assistance at state and local eligibility offices or through community-based assisters due to COVID-19.

CMS has recommended that states take steps to increase the share of online applications in a planning tool it developed to help states prepare for the end of the PHE. Electronic applications can expedite determinations and reduce both administrative costs and errors associated with manual data entry. As reported in the 2020 survey, the share of applications received online varies considerably among states, ranging from less than 10% to more than 90%. Both states that reported high and low shares of online applications in 2020 reported experiencing an increase in online applications. States can use a variety of strategies to increase the volume of online applications, including actively promoting the weblink in all outreach and marketing efforts and developing mobile-based apps and creating portals for assisters to facilitate applications.2

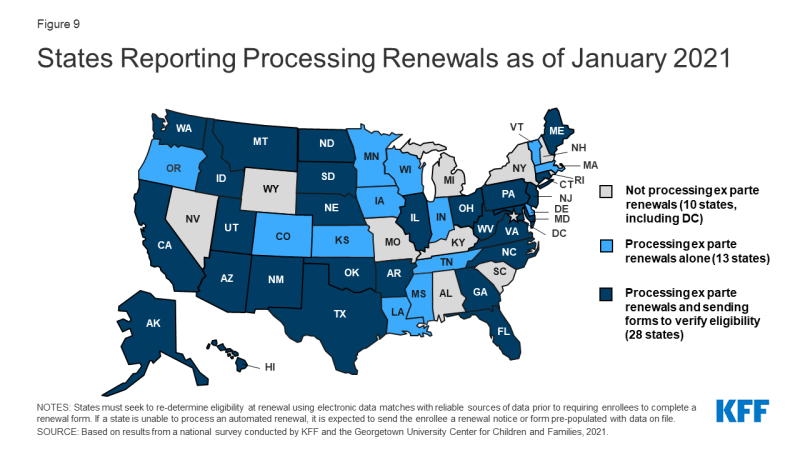

As of January 2021, most states (41) report processing ex parte (automated) renewals to extend coverage for individuals during the PHE (Figure 9) and two-thirds of those states (28 of 41) are sending renewal forms or requests for documentation when they are unable to confirm ongoing eligibility through electronic data sources. Under the ACA, states must seek to complete automated or ex parte renewals by verifying ongoing eligibility through available data sources, such as state wage databases, before sending a renewal form or requesting documentation from an enrollee. While some states suspended renewals as they implemented the MOE continuous coverage requirements and made other COVID-related adjustments to operations, most states are now actively processing renewals. Other states will likely restart the renewal process in response to CMS guidance that outlines actions states should take during the PHE to resume normal operations to the extent possible. When states are able to confirm ongoing eligibility on an ex parte basis, including the 41 states currently processing automated or ex parte renewals, they have the option to extend the renewal date out to 12 months from the original renewal date or 12 months from when the renewal was processed to stagger renewal dates, but this may result in renewal periods for enrollees that are shorter than 12 months. If an enrollee submits documentation to verify ongoing eligibility at renewal, the state must extend coverage for a full 12 months.

Slightly more than a third of states (19) have established a new 12-month renewal period when processing a change in circumstances that results in a new eligibility pathway. In November 2020, CMS published an interim final rule that provided options for states to transition enrollees determined ineligible for their current coverage to different coverage pathways for which they are eligible if such a transition is in the same tier of coverage (though it may cover fewer benefits or have higher patient cost-sharing). States may then retain the original renewal date or extend a new 12-month eligibility period if they have information needed to confirm ongoing eligibility. Some states report that pregnant women and children aging out of coverage are most likely to be given a new 12-month renewal period, while other states say enrollees in all MAGI-based eligibility groups are given a new 12-month renewal period.

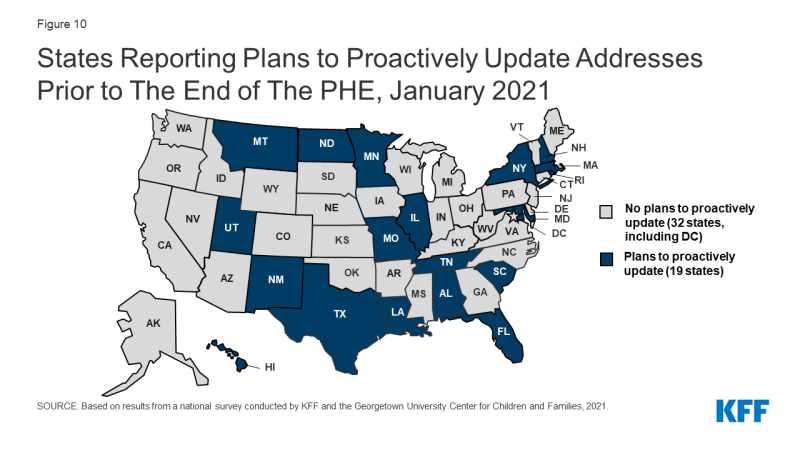

Just over one third of states (19) proactively take steps to update mailing addresses or plan to do so before the end of the PHE (Figure 10). Once the PHE expires and states resume normal operations under current federal rules, states may automatically terminate coverage without the advance ten-day notice when an enrollee cannot be located.3 Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, a number of states terminated coverage when mail was returned as undeliverable, potentially contributing to enrollment declines. Ongoing issues with the United States Postal Service (USPS) and the impact of the COVID-19 economic crisis on housing may exacerbate difficulties in reaching enrollees by mail. In 2020, states that took proactive steps to keep mailing addresses current reported using the USPS National Change of Address Database or contracting with vendors to facilitate the process. States may also check other public programs for more updated information or engage Medicaid managed care organizations in updating addresses. Additionally, as of 2020, 43 states offered online accounts, which make it easier for enrollees to update addresses among other features. A few states also reported taking additional action, such as attempting to contact enrollees via telephone.

Figure 10: States Reporting Plans to Proactively Update Addresses Prior to The End of The PHE, January 2021

Most states are not planning changes to eligibility or enrollment that are currently disallowed when the PHE ends. While all states will phase out the continuous coverage requirement, five states are planning to make other changes. Two states reported plans to move forward with implementing work requirements and three states plan to charge premiums for some adults. The Biden Administration has announced it intends to rescind work requirements demonstration waivers and may take additional action to revise waiver guidance, impacting states’ ability to implement these policies.

Looking Ahead

State eligibility and enrollment policies in place as of January 2021 provide a baseline for assessing state actions after the PHE ends and in response to new Medicaid policy options that may be adopted at the federal level. Currently, states cannot implement more restrictive eligibility policies than those in place as of January 1, 2020 and must provide continuous coverage to Medicaid enrollees until the PHE ends in order to receive enhanced federal funding. Their policy choices at the end of the PHE and decisions around adopting potential coverage options will have coverage implications for those who are currently enrolled and those who may become eligible.

The Biden Administration’s recent announcement regarding the likely extension of the PHE gives states more time to prepare for the end the PHE. In a letter to Governors, the Biden administration noted that the PHE is likely to extend for the entirety of 2021 and promised a 60-day notice before the PHE is terminated or is allowed to expire. Advance notice before the end of the PHE was one of the top responses when states were asked what additional guidance they need from CMS to plan for resuming normal operations.

States are taking steps now to prepare for the end of the PHE, but some indicate additional guidance would be helpful to reduce backlogs and minimize coverage disruptions. While most states are processing automated renewals when possible, states will still have a backlog of renewals that were not able to be completed. Some states noted the need for additional guidance to avoid unevenly distributed workloads due to large numbers of renewals and other changes occurring in a short period of time. When the PHE ends, CMS guidance issued under the Trump administration allows states to send coverage termination notices to individuals who did not respond to requests for information, did not return renewal forms, or lost eligibility for other reasons within six months of the end of the PHE. This approach may result in coverage losses at the end of the PHE for individuals who remain eligible. CMS guidance also gives states six months to catch up on pending renewals and other changes once the PHE ends; however, several states indicated that 12 months would allow for a smoother resumption of operations. While states can use this guidance to help plan for the end of the PHE, it is possible the Biden administration could revise the guidance, which would affect states’ planning efforts.

As states prepare to return to normal operations at the end of the PHE, there are additional considerations beyond resuming routine eligibility and enrollment procedures. In addition to the MOE requirements, states implemented a variety of temporary strategies to deal with the pandemic including, but not limited to eligibility, enrollment or renewal. These changes were wide ranging, impacting all aspects of Medicaid from improving access to telehealth and easing prior authorization requirements to waiving premiums or cost-sharing and modifying appeals and fair hearing requirements. CMS has developed two planning tools to aid states in preparing for the end of the PHE. The first focuses on eligibility and enrollment pending actions and the second provides assistance in general planning to restore regular Medicaid and CHIP operations. Together, the tools prompt states to consider actions that will aid in a smooth return to normal operations, including how they communicate with beneficiaries and stakeholders and how to extend or permanently implement flexibilities adopted through Section 1135 emergency waivers or disaster-related temporary state plan amendments.

Administration actions and Congressional proposals would reduce some barriers to Medicaid enrollment and support targeted Medicaid coverage expansions. The Biden administration has already reopened the marketplace and will restore funding for outreach, marketing and consumer assistance that will help connect uninsured individuals with Medicaid and CHIP. The administration also recently announced it will revise waiver demonstration policy and rescind guidance related to work requirements and may also revise demonstration policy related to capped financing. In addition, the latest COVID relief legislative package includes provisions to provide states the option to extend coverage for pregnant women to 12 months postpartum in both Medicaid and CHIP and to provide financial incentives for non-expansion states to adopt the Medicaid expansion.