Loneliness and Social Isolation in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan: An International Survey

Section 2: The Public’s Perceptions of Loneliness and Social Isolation

Awareness and Views of the Issue

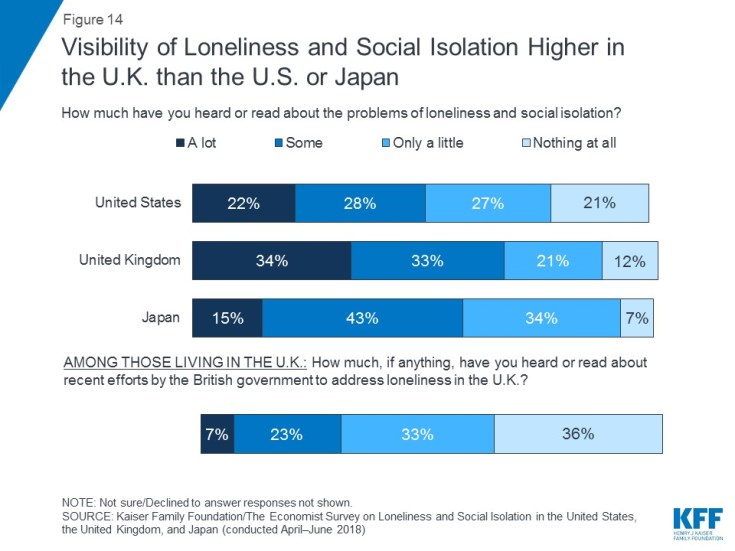

Across the U.S., the U.K., and Japan, majorities say they have heard “a lot” or “some” about the issue of loneliness and social isolation in their country. Not surprisingly given recent efforts by the U.K. government to address the issue, visibility is highest in the U.K. with two-thirds (67 percent) saying they’ve heard at least something about it, followed by 58 percent in Japan and 51 percent in the U.S. In the U.K., where a new minister for loneliness was appointed earlier this year, three in ten say they have heard or read “a lot” or “some” about recent efforts by the British government to address loneliness in the U.K. Another third say they’ve heard or read “only a little” and another third say they’ve heard “nothing at all.”

Who do people think of as being lonely? The most frequent answer is older people, with nearly three quarters of people in the U.K. (73 percent) and about half in the U.S. (49 percent) and Japan (46 percent) volunteering this group in an open-ended question. About four in ten people in Japan (43 percent) say when they think about people in Japan who are lonely, they think of people who live alone or are introverts, and nearly a fifth in the U.K. and the U.S. say the same. Additionally, about a fifth of adults in the U.S. and U.K. say they think of children, teenagers or young adults when they think of people who are lonely, compared to just six percent in Japan.

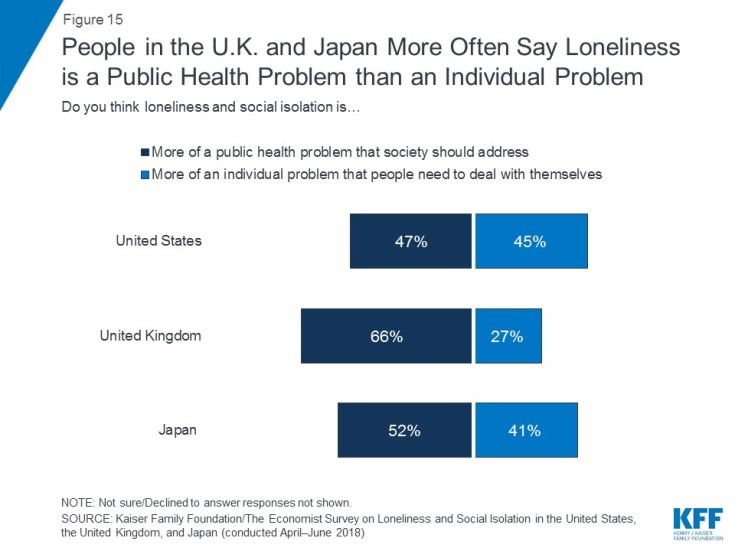

Across countries, views vary as to whether loneliness is more of a public health problem or more of an individual problem. In the U.K., and to a lesser extent Japan, more say it is more of a public health problem than say it is more of an individual problem (66 percent vs. 27 percent in the U.K. and 52 percent vs. 41 percent in Japan), whereas Americans are divided (47 percent vs. 45 percent).

Figure 15: People in the U.K. and Japan More Often Say Loneliness is a Public Health Problem than an Individual Problem

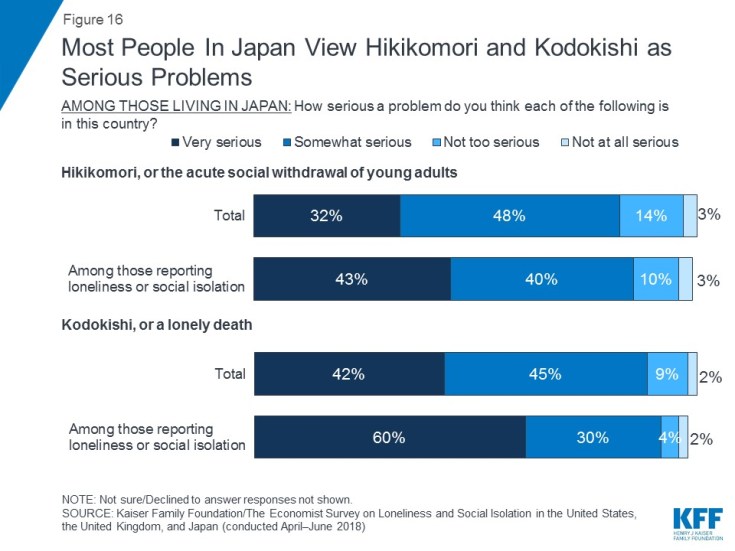

Japan has unique terms for two specific conditions related to loneliness. One is Hikikomori, or the acute social withdrawal of adolescents and young adults, and the other is Kodokishi, which refers to the concept of dying alone. In Japan, eight in ten or more say that these are very or somewhat serious problems. Those reporting loneliness in Japan are more likely than others to say Hikikomori and Kodokishi are “very” serious problems (43 percent vs. 31 percent and 60 percent vs. 40 percent, respectively).

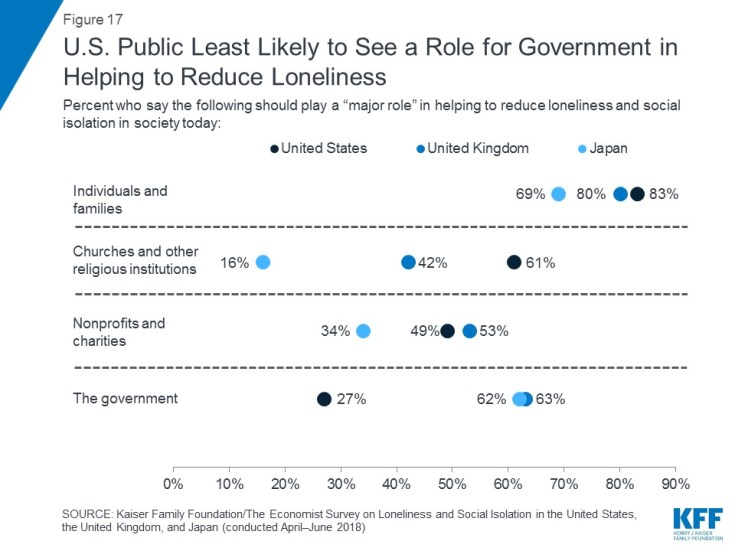

Across countries, large majorities of people say individuals and families should play a major role in helping to reduce loneliness and social isolation in society today. However, just about a quarter of Americans (27 percent) say the government should play a major role, whereas six in ten people in the U.K. (63 percent) and Japan (62 percent) see a major role for the government. Instead, more Americans see a major role for churches and other religious institutions (61 percent) than in the U.K. (42 percent) and Japan (16 percent).

Perceptions of Reasons for Loneliness

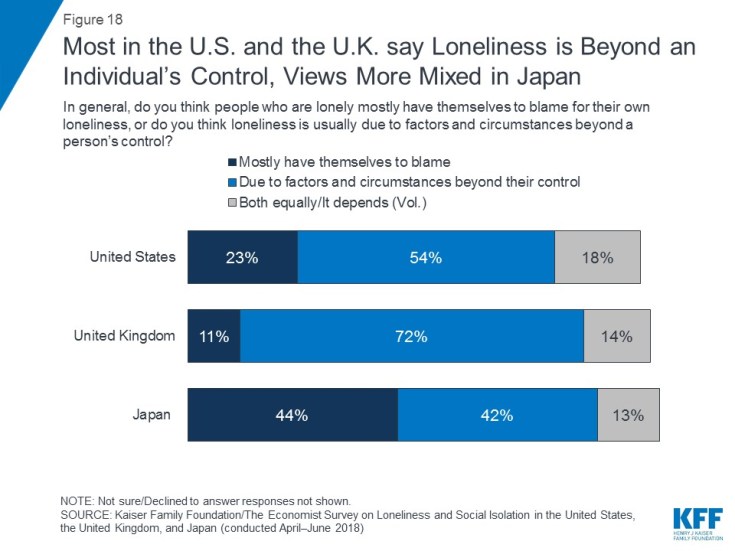

When asked how much responsibility individuals bear for their own loneliness, over half of Americans (54 percent) and seven in ten British people (72 percent) say a person’s loneliness is usually due to factors and circumstances beyond their control, rather than saying they mostly have themselves to blame. The Japanese are more divided with similar shares saying lonely people mostly have themselves to blame and saying loneliness is due to factors out of their control (44 percent and 42 percent, respectively). However, among people experiencing loneliness in Japan, 57 percent say a person’s loneliness is due to factors beyond their control.

Figure 18: Most in the U.S. and the U.K. say Loneliness is Beyond an Individual’s Control, Views More Mixed in Japan

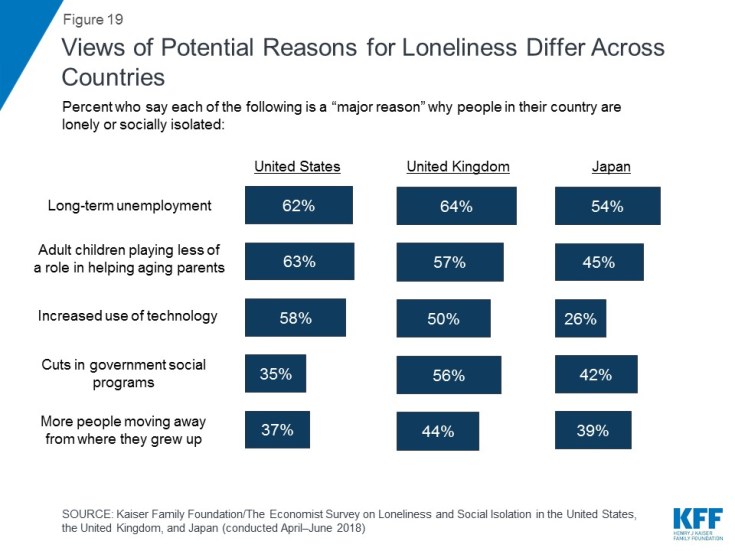

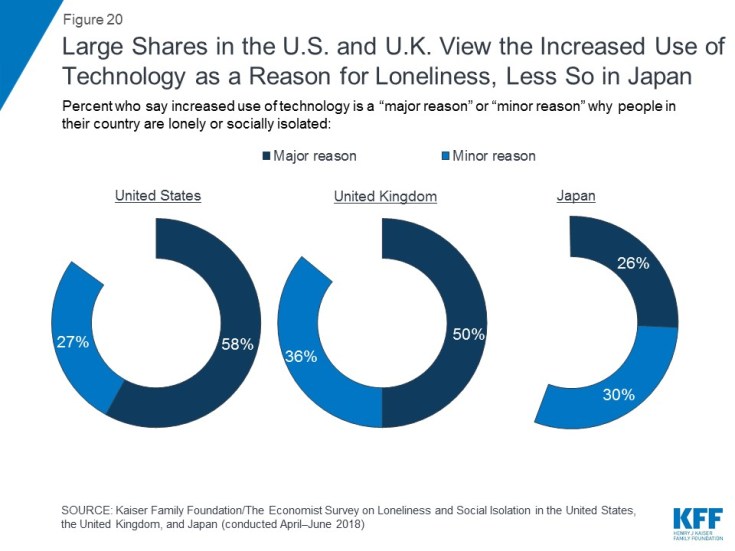

There are a number of different societal factors that may play a role in loneliness and social isolation and views of these potential reasons for loneliness differ across the U.S., U.K. and Japan. In one place of agreement, majorities across countries say that long-term unemployment is a major reason why people are lonely or socially isolated in their country. Much of the public in the U.S. and U.K. point to increased use of technology and adults playing less of a role in helping aging parents as major reasons, whereas fewer in Japan say the same. In addition, residents of the U.K. are more likely than those in the U.S. to say people moving away from where they grew up is a major reason for loneliness. Residents of the U.K. are also more likely than people in the U.S. or Japan to say cuts in government social programs is a major reason for loneliness. Views are similar regardless of whether or not someone reports personally experiencing loneliness or social isolation themselves.

One striking difference across countries is in the shares saying “increased use of technology” is a major reason people are lonely or socially isolated – from 58 percent in the U.S., to 50 percent in the U.K. and 26 percent in Japan. When including “minor” reason, the shares in the U.S. (84 percent) and U.K. (86 percent) are similar, but in Japan, it is just over half (56 percent).

Figure 20: Large Shares in the U.S. and U.K. View the Increased Use of Technology as a Reason for Loneliness, Less So in Japan

Social Media and Loneliness

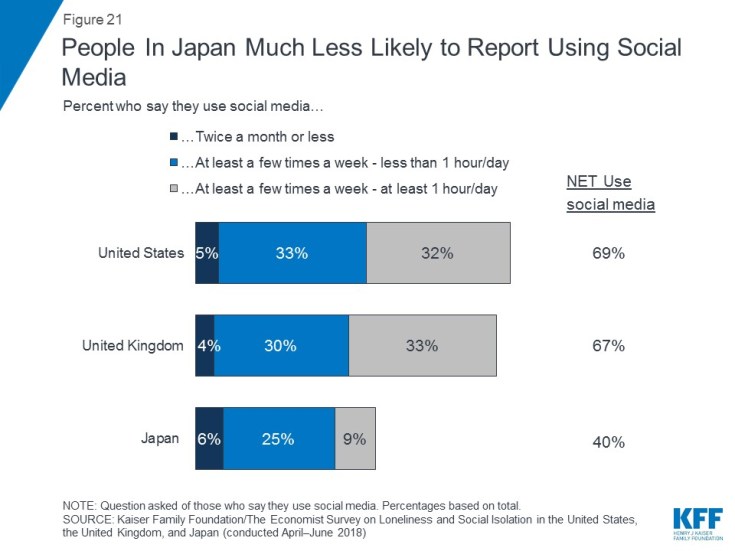

Social media consumption varies across the three countries from four in ten in Japan saying they use it, including 23 percent who say they use it every day, to 69 percent in the U.S. and 67 percent in the U.K., including nearly half in the U.S. and U.K. who say they use it every day, some of them for hours a day.

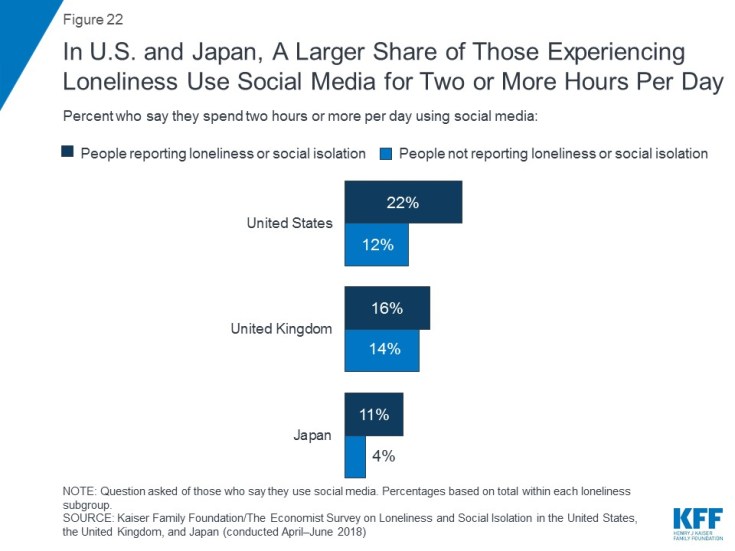

For the most part, people who report being socially isolated or lonely in each country are not more likely than their peers to report using social media. However, those experiencing loneliness in the U.S. and Japan are more likely than others to say they use social media for 2 hours or more per day (22 percent vs. 12 percent in the U.S. and 11 percent vs. 4 percent in Japan).

Figure 22: In U.S. and Japan, A Larger Share of Those Experiencing Loneliness Use Social Media for Two or More Hours Per Day

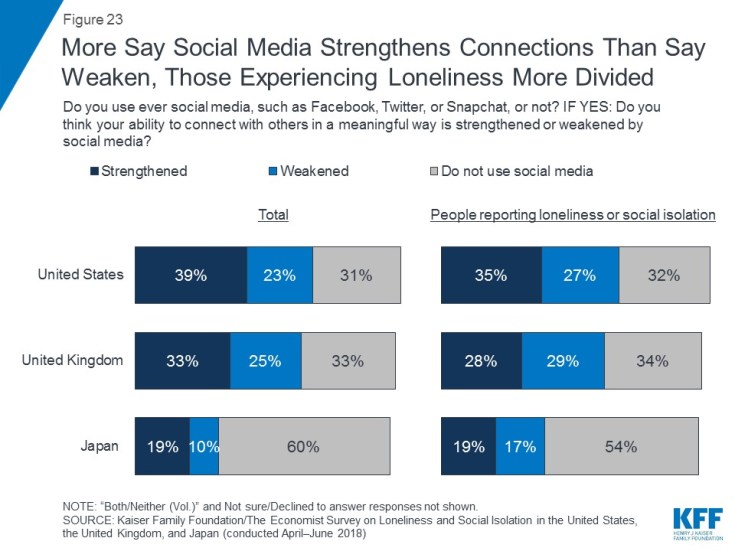

In each country, more of the public overall says that they think their ability to connect with others in a meaningful way is strengthened by social media than say it is weakened. However, those who are experiencing loneliness are more divided.

Figure 23: More Say Social Media Strengthens Connections Than Say Weaken, Those Experiencing Loneliness More Divided

On the question of whether one’s personal feelings of loneliness are made better or worse by social media, roughly similar shares of those experiencing loneliness in the U.S., U.K., and Japan say better or say worse.

Figure 24: Those Reporting Loneliness Roughly Split on Whether Social Media Improves or Worsens Feelings

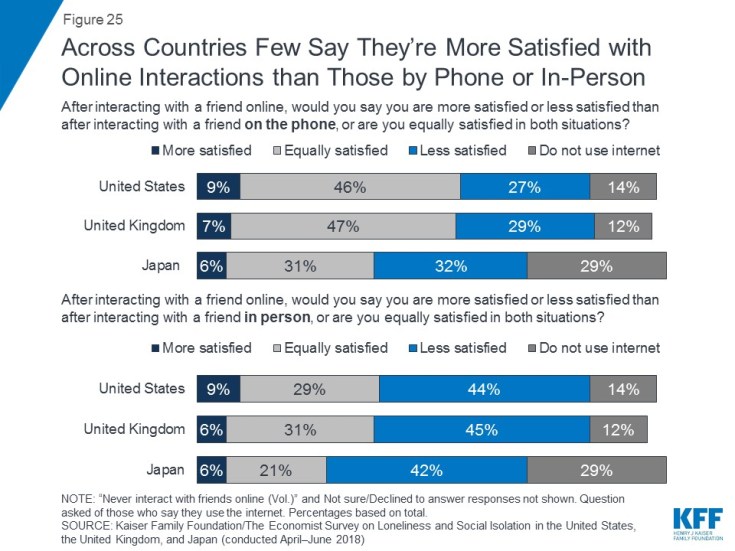

Most people in the U.S. and U.K. say that after interacting with a friend online they’re as satisfied as they would be after interacting with a friend on the phone. Still more say they feel less satisfied with this type of interaction than say they leave more satisfied. In Japan, views are more mixed with similar shares saying they they’re less satisfied (32 percent) as saying they’re equally satisfied (31 percent) when interacting via phone compared to online. However, when comparing an online interaction to an in-person interaction, across countries about four in ten say they’re less satisfied after interacting online, while fewer say they’re equally satisfied or more satisfied.

Figure 25: Across Countries Few Say They’re More Satisfied with Online Interactions than Those by Phone or In-Person

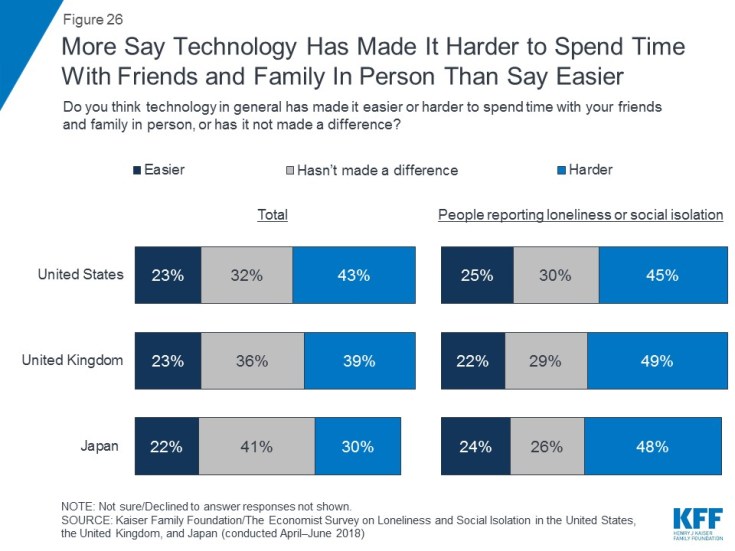

More broadly, across countries, more say technology in general has made it harder to spend time with friends and family in person than say it has made it easier. A third or more say it hasn’t made a difference. People experiencing loneliness or social isolation in the U.K. or Japan are more likely than others to say technology has made it harder to spend time with family and friends. In the U.S., shares are similar for those who are experiencing loneliness and those who aren’t.