Key Themes in Medicaid Section 1115 Behavioral Health Waivers

Introduction

Nearly half the states (22) have an approved and/or pending Section 1115 Medicaid demonstration waiver that involves one or more behavioral health initiatives as of November, 2017 (Figure 1). Behavioral health includes mental health and/or substance use disorders. Section 1115 of the Social Security Act allows the Health and Human Services Secretary to waive certain provisions of federal Medicaid law for an “experimental, pilot, or demonstration project” that “is likely to assist in promoting the objectives of” the program. State interest in Section 1115 Medicaid waivers related to behavioral health is high, driven in part by state efforts to address the opioid epidemic.

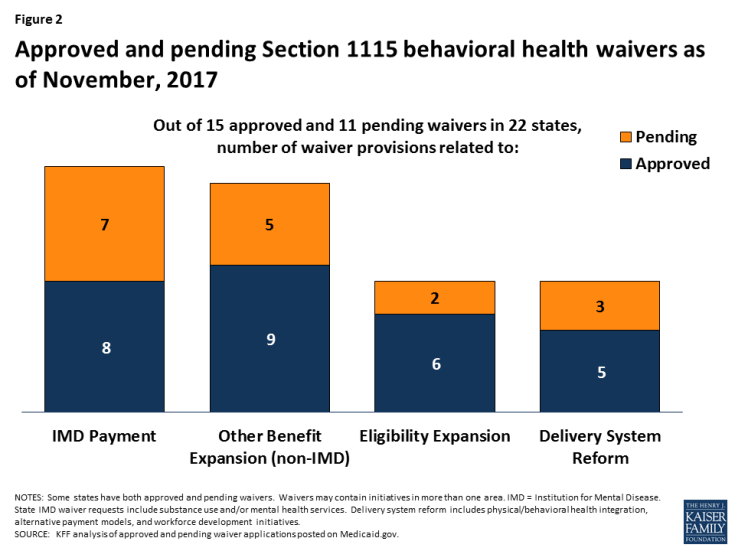

Figure 1: States with approved and/or pending Section 1115 behavioral health waivers, as of November, 2017

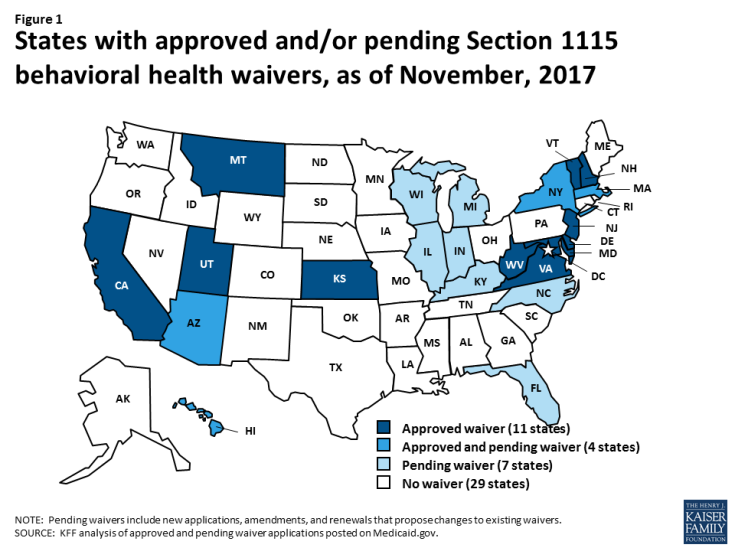

Current and pending Section 1115 behavioral health waivers address four main areas (Figure 2). These include using Medicaid funds to pay for substance use and/or mental health services in “institutions for mental disease” (IMDs), expanding community-based behavioral health benefits, expanding Medicaid eligibility to cover additional people with behavioral health needs, and financing delivery system reforms, such as physical and behavioral health integration or alternative payment models. This issue brief describes recent Section 1115 behavioral health waiver activity and highlights state examples and issues to watch in these four areas. The Appendix contains detailed tables about the 15 approved and 11 pending Section 1115 waivers related to behavioral health in 22 states as of November, 2017.

Using Federal Medicaid Funds for IMD Services

Since the creation of the Medicaid program, federal law has prohibited states from using Medicaid funds to pay for IMD services for non-elderly adults. The IMD payment exclusion generally applies to inpatient behavioral health facilities with more than 16 beds and was aimed at preserving the state financing of these services that pre-dated the Medicaid program. CMS’s 2016 revision of the Medicaid managed care regulations provides an exception to the IMD payment exclusion; the regulations now codify long-standing federal policy and permit states to use federal Medicaid funds for capitation payments to managed care plans that cover IMD inpatient or crisis residential behavioral health services for non-elderly adults “in lieu of” other services covered under the state plan.1 Under the regulation, which took effect in July, 2016, IMD services must be determined to be medically appropriate and cost-effective and are limited to 15 days per month,2 and enrollees cannot be required to accept IMD services instead of those that are covered under the Medicaid state plan.

Section 1115 IMD payment waivers distinguish between substance use disorder services and mental health services. Of the eight states with approved IMD payment waivers, seven have authority for substance use services and one has authority for mental health services. Of the seven states with pending IMD payment waivers, all seven are seeking new or expanded authority for substance use services, and two also are seeking authority for mental health services.

IMD Substance Use Disorder Services

Seven states (California, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Utah, Virginia, and West Virginia) have waiver authority to use federal Medicaid funds to pay for IMD substance use treatment services (Table 1). The day limits authorized under these waivers vary by state. Maryland’s waiver allows two 30-day stays, while California has approval for two 90-day stays for adults and two 30-day stays for adolescents.3 New Jersey, Utah, Virginia and West Virginia were approved without an explicit day limit. (California, Virginia, and West Virginia’s waivers all note that the average length of stay is 30 days.) Massachusetts has waiver authority for specified diversionary behavioral health services in IMDs provided by managed care plans, expanded substance use treatment services in IMDs provided to all full benefit enrollees regardless of delivery system, and payments to IMDs through the waiver’s safety net care pool.4 Most of these waivers were approved pursuant to CMS’s July, 2015 guidance that allows states to use Section 1115 waivers to test using federal Medicaid funds to provide a full continuum of substance use disorder treatment services, including short-term inpatient and residential IMD services.5 On November 1, 2017, the Trump Administration issued a state Medicaid director letter revising the July, 2015 guidance.6 For more details on the CMS guidance, see Box 1 below.

| Box 1: CMS Guidance on Section 1115 IMD Substance Use Disorder Payment Waivers |

| On July 27, 2015, CMS issued a state Medicaid director letter allowing states to obtain Section 1115 waivers of the federal IMD payment exclusion for substance use treatment services. The IMD waiver authority was contingent on states covering community-based services7 along with short-term institutional services that “supplement and coordinate with, but do not supplant, community-based services.”8 States also were expected to implement delivery system and practice reforms that integrated physical and behavioral health care and used evidence-based industry standards.9

On November 1, 2017, CMS issued a state Medicaid director letter revising the July, 2015 guidance.10 The revised guidance continues to allow states to use Section 1115 waivers to pay for IMD substance use treatment services and affirms many components of the earlier guidance. For example, it notes that “states should indicate how inpatient and residential care will supplement and coordinate with community-based care in a robust continuum of care in the state” and directs states to “demonstrate how they are implementing evidence-based treatment guidelines.”11 The revised guidance requires certain demonstration components, such as residential treatment provider qualifications and capacity, opioid prescribing guidelines, access to naloxone, prescription drug monitoring programs, and care coordination between residential and community settings. States must report on core and state-specific quality measures, perform waiver evaluations, and are subject to a $5 million deferral per item for failure to comply with evaluation and reporting requirements. |

| Table 1: Section 1115 IMD Payment Waivers as of November, 2017 | ||

| # of States | States | |

| Approved Waiver Provisions (8 states) | ||

| IMD Substance Use Treatment Services | 7 | CA, MD, MA, NJ, UT, VA, WV |

| IMD Mental Health Services | 1 | VT |

| Pending Waiver Requests (7 states) | ||

| IMD Substance Use Treatment Services | 7 | AZ, IL, IN, KY, MA, MI, WI |

| IMD Mental Health Services | 2 | IL, MA |

| SOURCE: KFF analysis of Section 1115 waivers posted on Medicaid.gov. | ||

IMD Mental Health Services

One state (Vermont) has waiver authority to use federal Medicaid funds to pay for IMD mental health treatment services, although those payments must be phased out (Table 1).12 Vermont’s waiver requires it to submit a schedule by the end of 2018 to begin reducing federal Medicaid IMD spending in January, 2021, and completely end this spending by the end of 2025. Vermont’s waiver also requires the state to evaluate the impact of federal IMD spending on people with serious mental illness and those in need of acute behavioral health services who reside in IMDs in the context of system-wide service, payment, and delivery system reform.

What to Watch

IMD payment waivers are currently the most frequently sought type of Section 1115 behavioral health waiver request. Seven states are seeking IMD substance use treatment waivers, including new waiver requests in six states (Arizona, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Michigan, and Wisconsin) and a request to expand existing waiver authority in one state (Massachusetts). Two states (Illinois and Massachusetts) also have pending requests for IMD mental health waivers (Table 1). State proposals for the length of IMD stay vary. Among states seeking IMD substance use waivers, Illinois, Indiana, and Kentucky propose 30-day stays, Wisconsin proposes a 90-day stay, and Arizona and Michigan do not specify a day limit. (Arizona notes that it previously covered IMD stays without a day limit under managed care “in lieu of” authority before the Medicaid managed care rule was revised in 2016.) Massachusetts’ pending waiver amendment seeks to remove all federal IMD payment restrictions on both substance use and mental health services, including the 15-day limit for managed care plans and the cap on safety net care pool payments. In addition to 30-day substance use treatment stays, Illinois also proposes a 30-day IMD stay for mental health services.

A key issue to watch in IMD payment waivers is how CMS and states will balance expanding institutional services while also ensuring access to community-based services and preventing unnecessary institutionalization. Stakeholders may look to trends around day limits, community-based service expansions, and delivery system reforms that may be included in CMS’s approval of pending and future IMD payment waivers as well as performance measure and waiver evaluation results from approved waivers. Stakeholders particularly may want to watch CMS’s response to state requests for IMD mental health payment waivers, as the IMD payment waiver guidance does not address mental health services. Waiving the IMD payment exclusion and expanding institutional services without adequate access to community-based services could have implications for states’ community integration obligations under the Supreme Court’s Olmstead decision if people with disabilities are inappropriately institutionalized.13

Expanding Community-Based Behavioral Health Benefits

Although many community-based behavioral health benefits can be covered under Medicaid state plan authority, some states seek waiver authority to cover certain community-based behavioral health benefits. States may not need waiver authority to provide these benefits; for example, West Virginia’s recent waiver approval notes that the state has opted to cover peer recovery coaching and methadone under waiver expenditure authority, even though those services could be covered under state plan authority. Other services, such as certain home and community-based services (HCBS) for people who would otherwise qualify for an institutional level of care, may require waiver authority. Historically, states have used Section 1915 (c) waivers to provide HCBS, although CMS also has authorized HCBS under Section 1115 waivers.

Nine states have Section 1115 waivers that expand community-based Medicaid behavioral health benefits beyond those available in the state plan benefit package (Table 2). These states include Delaware, Hawaii, Kansas, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Vermont, and West Virginia. Three states (Delaware, Hawaii, and Maryland) offer supportive housing services, such as community transition services for people leaving institutional placements, tenancy supports, household activity skill building and chore services, and/or case management.14 Three states (Delaware, Hawaii, and Vermont) offer supported employment services, such as job coaching. Two states (Massachusetts and West Virginia) offer peer recovery coaching services. Eight states offer other community-based behavioral health services (Table 2). For example, Massachusetts offers community-based services intended to divert individuals with behavioral health needs from institutional stays, such as community crisis stabilization, community support program, psychiatric day treatment, intensive outpatient, and assertive community treatment services.

| Table 2: Section 1115 Behavioral Health Benefit Expansion Waivers as of November, 2017 | ||

| # of States | States | |

| Approved Waiver Provisions (9 states) | ||

| Supportive Housing | 3* | DE, HI, MD |

| Supported Employment | 3 | DE, HI, VT |

| Peer Recovery Coaching | 2 | MA, WV |

| Other Community-Based Behavioral Health Services | 8 | DE, HI, KS, MA, NJ, NY, VT, WV |

| Specialized Behavioral Health Benefit Package | 4 | DE, NJ, NY, VT |

| Pending Waiver Requests (5 states) | ||

| Supportive Housing | 4 | FL, HI, IL, MI |

| Supported Employment | 1 | IL |

| Peer Recovery Coaching | 2 | IL, MI |

| Other Community-Based Behavioral Health Services | 3 | IL, MI, NY |

| NOTES: *CA’s Whole Person Care pilot also includes waiver funding for services not otherwise covered under Medicaid, such as supportive housing. SOURCE: KFF analysis of Section 1115 waivers posted on Medicaid.gov. |

||

Four states with approved waivers (Delaware, New Jersey, New York, and Vermont) have designed specialized benefit packages that provide expanded behavioral health services (Table 2). These services are targeted to individuals who need supportive services to live in the community and meet certain diagnosis and/or risk criteria. Delaware and New York target adults, while New Jersey and Vermont target children and youth under age 21 and their families. Delaware’s benefit package is provided fee-for-service and includes a case manager from the state’s mental health and substance abuse agency, while New York’s benefit package is offered through a specialized managed care plan.

What to Watch

Five states (Florida, Hawaii, Illinois, Michigan, and New York) have pending waiver requests to expand community-based behavioral health benefits (Table 2). The most frequently sought type of benefit is supportive housing; four states (Florida, Hawaii, Illinois, and Michigan) are proposing waivers to provide or expand supportive housing services for people with behavioral health diagnoses who are homeless or at risk of homelessness. One state (Illinois) is seeking waiver authority to offer supported employment services. Two states (Illinois and Michigan) have pending requests to offer peer recovery coaching services. Three states have pending proposals for other community-based behavioral health benefits (Table 2). For example, Illinois proposes to cover certain behavioral health services for people who are incarcerated within 30 days of their release to smooth the transition to the community. These services would include screening and assessment, identification of a post-release provider, one outpatient visit, and extended release naltrexone.

The impact of behavioral health benefit expansions on enrollees’ access to community-based care, health outcomes, and costs will be an important area to watch. States continue to rely on federal Medicaid funds to meet their Olmstead community integration obligations and rebalance long-term care spending in favor of community-based services instead of institutional care. Historically, fewer states have offered community-based long-term care services to people with behavioral health needs compared to other populations, such as seniors, people with physical disabilities, and people with intellectual or developmental disabilities.15 In recent years, states have increasingly taken advantage of benefits and federal financing incentives made available under the ACA to serve people with behavioral health needs in the community.16 Section 1115 waiver evaluations and other reports and data from waiver implementation can help CMS, states, health plans, and providers better understand how to design and deliver these benefits.

Expanding Eligibility for People with Behavioral Health Needs

States use waiver authority to cover people with behavioral health needs who are not otherwise eligible for Medicaid and to place enrollment caps on eligibility expansions targeted to people with behavioral health needs. States do not need waiver authority to expand Medicaid eligibility for many people with behavioral health needs. Instead, states can use Section 1915 (i) state plan authority to expand Medicaid eligibility to targeted groups of people who are at risk of an institutional level of care (including those with behavioral health needs) up to 150% FPL or up to 300% SSI for those who would be eligible under an existing home and community-based services waiver.17 Section 1115 waiver authority allows states to cap enrollment, while Section 1915 (i) allows states to control enrollment by expanding or restricting functional eligibility criteria.18

Six states (Arizona, Montana, New Jersey, Utah, Vermont, and Virginia) have Section 1115 waivers that expand Medicaid eligibility to cover people with behavioral health needs (Table 3). Four of these states (Arizona, Montana, New Jersey, and Vermont) have adopted the ACA expansion to cover nearly all adults up to 138% FPL and are using waiver authority to further expand Medicaid eligibility to targeted groups of people with behavioral health needs. Arizona’s waiver expands its long-term care eligibility criteria to cover non-elderly adults up to 300% of SSI who do not currently require an nursing home level of care but are at risk of nursing home care due to mental illness.19 Montana’s waiver expands its financial eligibility criteria to cover non-elderly adults with “severe disabling mental illness”20 who do not qualify for the ACA expansion (139-150% FPL for Medicaid-only enrollees and up to 138% FPL for those dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid).21 New Jersey’s waiver expands financial and functional eligibility criteria to cover two targeted groups of children ages 0-21 with behavioral health needs: children with serious emotional disturbance (up to 300% SSI if otherwise state plan eligible22 and up to 150% FPL for those not otherwise eligible23) and children with qualifying intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD) and co-occurring mental illness up to 300% FPL.24 Vermont’s waiver funds coverage for mental health community rehabilitation and treatment services provided under a state program for people with serious and persistent mental illness from 133-185% FPL.25 The other two states (Virginia and Utah) have not adopted the ACA expansion but use waiver authority to expand coverage to adults with behavioral health needs. Virginia offers a limited physical and behavioral health benefit package to uninsured adults with serious mental illness up to 100% FPL, and Utah covers childless adults up to 5% FPL who are (in order of priority) chronically homeless, involved in the criminal justice system and in need of behavioral health treatment, or in need of behavioral health treatment.

| Table 3: Section 1115 Behavioral Health Eligibility Expansion Waivers as of November, 2017 | ||

| # of States | States | |

| Approved Waiver Provisions (6 states) | ||

| Behavioral Health Eligibility Expansion | 6 | AZ, MT, NJ, UT, VT, VA |

| Pending Waiver Requests (4 states) | ||

| Behavioral Health Eligibility Expansion | 2 | NJ, NY* |

| Enrollment and Renewal Modification | 1 | IL |

| NOTE: *New York’s pending waiver amendment also would move its existing financial eligibility expansion for children with behavioral health and HCBS needs who currently meet an institutional level of care from Section 1915 (c) to Section 1115 authority. SOURCE: KFF analysis of Section 1115 waivers posted on Medicaid.gov. |

||

Some states are using waiver authority to limit enrollment in their behavioral health eligibility expansions. Three states (Montana, New Jersey, and Vermont) have Section 1115 waiver authority to cap the number of people covered under their behavioral health eligibility expansions that cover additional populations beyond the ACA expansion to all adults up to 138% FPL (there is no enrollment cap on the ACA expansion population). Another state (Virginia) does not impose a numerical cap on its targeted behavioral health eligibility expansion but has periodically amended the financial eligibility limit under the waiver to control the number of people who qualify for coverage.

What to Watch

Two states (New Jersey and New York) have pending waivers that would provide Medicaid eligibility for people with behavioral health needs (Table 3). New Jersey and New York have adopted the ACA’s Medicaid expansion and are seeking to further expand eligibility to people with behavioral health needs. New Jersey and CMS are working to finalize approval for a waiver pilot program to provide HCBS to adults with I/DD and acute behavioral health needs. New York is seeking to expand financial and functional eligibility to provide HCBS for children with behavioral health needs who are at risk of institutional care without regard to parental income.26

Additionally, one state (Illinois) is seeking waiver authority that would not authorize a new coverage pathway but instead would modify enrollment and renewal rules to facilitate coverage for Medicaid-eligible people being released from prison or jail (Table 3). Specifically, Illinois proposes to auto-assign incarcerated individuals to managed care plans as early as possible within 30 days of their release and defer eligibility renewals until 180 days post-release. While most state waiver activity related to eligibility is related to eligibility expansions, one state (Wisconsin) has a pending waiver that could restrict the enrollment of eligible people into coverage. Box 2 provides more information about Wisconsin’s proposal.

| Box 2: Wisconsin’s Proposed Section 1115 Waiver Provision on Drug Screening and Testing |

| Wisconsin has a pending waiver request to condition Medicaid eligibility for childless adults on completing drug screening and testing, and if indicated, entering treatment. Specifically, childless adults (who are covered up to 100% FPL under Wisconsin’s waiver) would have to complete a screening questionnaire about their current and prior substance use, and if indicated, a drug test, at application and renewal. Those who indicate on the questionnaire that they are ready to enter treatment could forgo the drug test and enter treatment. Those who test positive for a controlled substance without evidence of a valid prescription would have eligibility conditioned on completing treatment, although eligibility would continue if treatment was not immediately available. Those who refuse to participate in treatment would lose eligibility but could re-apply at any time. CMS has never before conditioned Medicaid eligibility on drug screening, testing, or treatment. |

Key issues to watch regarding eligibility expansion waivers include the effect of coverage on enrollees’ access to needed physical and behavioral health care, health outcomes, and costs. An evaluation of the first year of Virginia’s behavioral health eligibility expansion (January to December 2015) found that providing coverage is cost-effective, as the average monthly cost of coverage was $200 less than a single emergency room visit for a “very minor” condition ($418 vs. $687).27 About ¾ of waiver enrollees had a claim for behavioral health services, and just over half had a claim for physical health services.28 Virginia is going to further explore enrollees who were identified as being prescribed medication but did not have a prescription drug claim.29 Virginia also noted some of the challenges associated with providing only a limited benefit package to its behavioral health expansion enrollees, including the unmet need for transportation, particularly to access substance use disorder treatment services.30 The Virginia waiver evaluation also discusses the success of offering peer supports to waiver enrollees, describing their impact as “influential,” and the state’s decision to expand those services to all Medicaid enrollees as a result of the demonstration.31

Financing Behavioral Health Delivery System Reforms

States primarily seek waiver expenditure authority to provide federal funding for behavioral health delivery system reforms. Under federal law, states have flexibility to design their Medicaid delivery systems and typically can do so without seeking a waiver. However, states may seek waivers if they want to access federal Medicaid funds to support delivery system reforms.

Four states (Arizona, California, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire) have approved waivers to finance behavioral health delivery system reforms (Table 4). All include initiatives to better integrate physical and behavioral health care, and three (California, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire) including funding to help states transition to alternative payment models. Arizona offers specialized health plans that include both acute and behavioral health services for children with certain behavioral health conditions and adults with serious mental illness. California’s Whole Person Care pilots include funding to support infrastructure development focused on integrating services, improving health outcomes, and reducing unnecessary service use for high-cost, high-risk enrollees. California’s waiver also includes funding to support the state’s transition to risk-based alternative payment models. Massachusetts’ waiver funds the state’s transition to accountable care organizations that will integrate physical, behavioral health, long-term care, and health-related social services. New Hampshire’s waiver authorizes performance-based incentive payments to providers who integrate physical and behavioral health services, increase workforce capacity, develop information technology infrastructure, and better coordinate care.

| Table 4: Section 1115 Behavioral Health Delivery System Reform Waivers as of November, 2017 | ||

| # of States | States | |

| Approved Waiver Provisions (4 states)* | ||

| Physical/Behavioral Health Integration | 4 | AZ, CA, MA, NH |

| Transition to Alternative Payment Model | 3 | CA, MA, NH |

| Pending Waiver Requests (3 states) | ||

| Physical/Behavioral Health Integration | 3 | IL, MI**, NC |

| Transition to Alternative Payment Model | 2 | MI, NC |

| Workforce Development Initiatives | 2 | IL, NC |

| NOTES: *While no specific waiver authority is granted, Maryland’s waiver commits the state to developing and implementing a physical/behavioral health integration model for individuals with substance use disorders by January 1, 2019 as part of its IMD payment waiver. **Michigan’s integration model currently exists under Section 1915 (b)/(c) authority that the state is seeking to convert to Section 1115. SOURCE: KFF analysis of Section 1115 waivers posted on Medicaid.gov. |

||

What to Watch

Three states (Illinois, Michigan, and North Carolina) have pending waivers seeking funding to support behavioral health delivery system reform initiatives (Table 4). All include provisions related to behavioral and physical health integration, two (Michigan and North Carolina) seek funding for alternative payment models, and two (Illinois and North Carolina) seek funding for workforce development initiatives. Specifically, Illinois seeks funding to support the development of technology and training to implement health homes and workforce development programs, including loan forgiveness and telemedicine infrastructure and training. Michigan is seeking waiver funding for alternative payment methodologies based on quality outcomes, shared savings/shared risk models, and incentives for care coordination for high utilizers. North Carolina’s waiver application mentions initiatives related to integrating behavioral health care into primary care settings, value and performance-based payments, a pilot special needs health plan targeted to people with serious and persistent mental illness, and funding for workforce training.32

CMS’s response to waiver requests to fund delivery system reform initiatives will be an important area for states to watch. CMS’s November, 2017 IMD payment waiver guidance confirms that the Medicaid Innovation Accelerator Program will continue to be available to help states improve their substance use treatment delivery systems. It not yet clear how CMS will respond to state requests to obtain federal funding for state-funded programs (“designated state health programs”) through waivers.

Looking Ahead

States’ Section 1115 waiver requests continue to reflect Medicaid’s important role in financing behavioral health coverage and can help CMS and states identify best practices, particularly related to state efforts to address the opioid epidemic. While different administrations may implement different policy priorities through waivers, CMS is continuing to allow states to use waivers to fund short-term IMD substance use treatment services. Key issues to watch related to Medicaid Section 1115 behavioral health waivers include how CMS and states will balance expanding institutional services while also ensuring access to community-based services and preventing unnecessary institutionalization; what impact benefit and eligibility expansions will have on health outcomes, access to care, and costs; and how CMS and states will use Section 1115 waivers to prioritize and implement delivery system reforms. As the Trump Administration issues more waiver decisions, other trends may become apparent which in turn could influence future state waiver requests related to behavioral health services, eligibility, and delivery system initiatives.