Improving the Affordability of Coverage through the Basic Health Program in Minnesota and New York

Executive Summary

To date, Minnesota and New York are the only states to have adopted a Basic Health Program (BHP), an option in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) that permits state-administered coverage in lieu of marketplace coverage for those with incomes below 200% of the federal poverty level (FPL) who would otherwise qualify for marketplace subsidies. BHP covers adults with incomes between 138-200% of FPL and lawfully present non-citizens with incomes below 138% FPL whose immigration status makes them ineligible for Medicaid. States implementing BHP receive 95% of what the federal government would have spent on subsidies if BHP enrollees had received marketplace coverage. Both states covered much of the BHP-eligible population prior to the ACA, which facilitated their adoption of BHP. Minnesota, in particular, adopted BHP to retain this prior coverage while saving state dollars. Based on semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders and policymakers in each state as well as reviews of policy documents and reports, this brief examines implementation of the BHP as of Summer 2016. It assesses the impact of BHP on consumers, the marketplaces, and state costs and financing. Although the 2016 election results create uncertainty around the future of the ACA (including BHP), BHP implementation provides important lessons about structuring coverage programs for low-income uninsured consumers for consideration in future reforms. Key findings include the following.

BHP programs in both Minnesota and New York provide coverage with lower premiums and cost-sharing compared to subsidized marketplace coverage. In New York, BHP enrollees with incomes at or below 150% FPL do not pay premiums while those with incomes between 150 and 200% FPL pay $20 per month. Sliding-scale premiums in Minnesota are higher than in New York but lower than for subsidized marketplace plans. According to stakeholders, an important feature of both programs is the absence of deductibles. Copayments are also generally lower than for QHPs. Both programs cover services in addition to essential health benefits for all or some BHP enrollees.

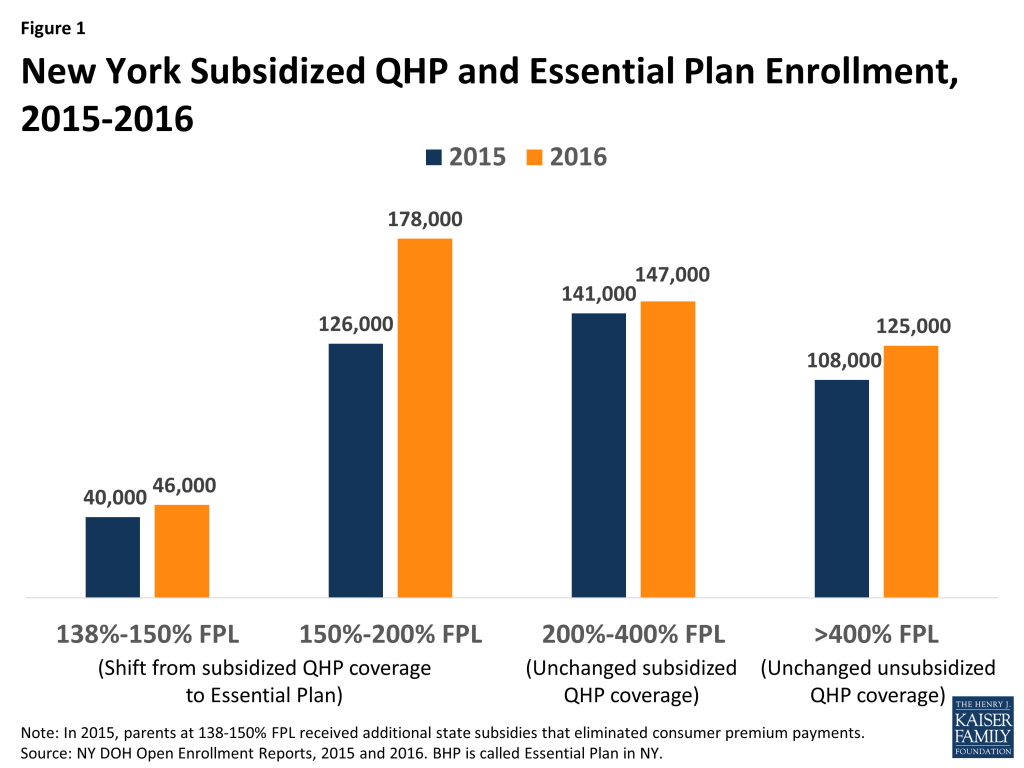

More affordable coverage led to increased enrollment in New York. When New York adopted the BHP in 2016, enrollment rose by 42% among those whose eligibility shifted from federally-subsidized QHPs to BHP. Enrollment increased by only 4% among subsidy-eligible adults unaffected by BHP implementation. Officials and stakeholders attributed the enrollment growth to BHP’s lower premiums and out-of-pocket cost-sharing compared to subsidized QHP coverage. Minnesota officials and stakeholders reached similar conclusions about the impact of affordability on enrollment. In both states, new enrollees attracted by more affordable coverage were described as relatively young and healthy. According to stakeholders, consumers also reported preferring the greater simplicity and predictability of BHP, compared to the marketplace.

BHP did not appear to affect marketplaces’ stability. New York officials reported that BHP implementation did not affect marketplace stability or carrier interest. Minnesota officials felt that the instability experienced in the state’s marketplace resulted from factors other than BHP; however, carriers suggested that BHP may have contributed by shrinking the marketplace’s size.

Most BHP insurers also participated in Medicaid and/or the marketplace. Minnesota conducted a joint procurement for Medicaid and BHP; carriers wishing to participate in one program had to join both, and many offered QHPs as well. In New York, 11 of 13 BHP plans participated in all three programs. This overlap helped consumers retain continuous coverage arrangements when income changes moved them between programs.

BHP enrollees whose incomes rose above 200% FPL experienced steep cost increases when they moved to QHPs. BHP’s more affordable coverage for enrollees ended at 200% FPL, so costs increased for those whose income rose above 200% FPL. Minnesota is exploring ways to smooth this “cliff” by expanding BHP eligibility above 200% FPL. Advocates in New York have called for a similar discussion of policy options.

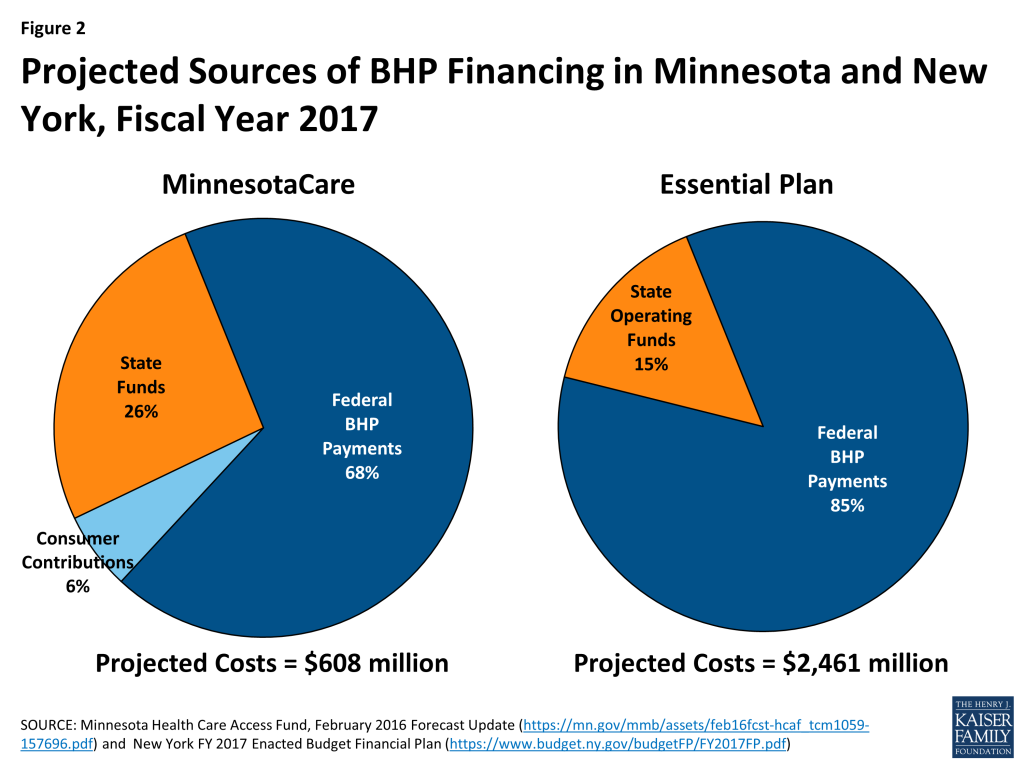

Both states experienced fiscal gains from BHP, but state financing was needed. Both states achieved administrative efficiencies by using existing state agencies to run BHP. Both states also realized significant net savings by using BHP to fund populations previously covered with state funds—lawfully present immigrants in New York, who had been receiving Medicaid funded entirely by the state; and the general BHP population in Minnesota, which previously covered them through a Medicaid waiver with standard federal matching rates. However, the federal BHP payments did not fully cover program costs in either state, requiring the states to finance a share of the costs. For fiscal year 2017, Minnesota expects to pay 26% of BHP costs while New York will fund 15%.

While the outcome of the 2016 election has created uncertainty around the future of the ACA, including BHP, the experiences of Minnesota and New York with BHP suggest broader lessons about coverage for low-income consumers. Chief among these lessons is the importance of affordability, both in terms of premiums and out-of-pocket costs. New York’s natural experiment shows with particular clarity that affordability improvements can yield significant enrollment gains and risk-pool improvements among the lowest-income consumers qualifying for marketplace subsidies. In addition, stakeholders reported that many consumers preferred the simplicity of state-administered coverage that offered consistency in premiums, cost-sharing, and benefits across participating plans over the complexity of marketplace plans. Encouraging a common set of plans and providers to participate across programs, including public programs and the private market, can promote continuity of coverage and care for consumers who move between programs when household circumstances change. Finally, relying on existing infrastructure to administer new coverage programs creates efficiencies and can help to avoid duplication.

Issue Brief

Introduction

The Basic Health Program (BHP) gives states the option of providing state-administered coverage in lieu of coverage through health insurance marketplaces to certain individuals with incomes at or below 200% of the federal poverty level (FPL). Soon after the enactment of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the BHP was broadly viewed as giving states the flexibility to provide more affordable coverage to low-income consumers and providing consumers with incomes up to 200% FPL with access to the same set of health plans. Because federal BHP regulations were delayed, states could not implement BHP until 2015. To date, two states, Minnesota and New York, have adopted BHP.

To learn about these states’ experiences with BHP, in Spring and Summer 2016 the Kaiser Family Foundation and the Urban Institute conducted semi-structured phone interviews with policymakers and stakeholders in Minnesota and New York. Interviewees included Medicaid and marketplace officials, consumer advocates, in-person assisters, and representatives from health plans and community health centers (CHCs). We also reviewed state policy documents and reports. This work builds on previous analyses that described federal regulations for the BHP and provided a roadmap to states interested in implementing the BHP for estimating the number of BHP-eligible people and approximate federal BHP payments.

This brief reviews Minnesota’s and New York’s approaches to BHP and assesses BHP’s impact on consumers, marketplaces, and state costs. Although there is uncertainty around the future of the ACA (including BHP) following the 2016 election, BHP implementation offers important lessons for consideration in future reforms about structuring coverage programs for low-income uninsured consumers.

Background

Federal BHP Rules

States can adopt the BHP to cover consumers with incomes up to 200% FPL who would otherwise qualify for subsidies in the marketplace. BHP is available to two groups of such consumers: those with incomes between 138-200% FPL; and lawfully present non-citizens with incomes at or below 138% FPL whose immigration status disqualifies them from federally-funded Medicaid (often because of lawful residence for less than five years). Coverage through BHP must be as comprehensive and affordable as subsidized coverage in the marketplace, though states can provide coverage beyond the essential health benefits and lower consumer costs. States implementing BHP receive 95% of what the federal government would have spent to subsidize BHP enrollees had they received marketplace coverage. While the ACA authorized states to implement BHP beginning January 2014, delays in issuing BHP regulations prevented states from implementing the program until January 2015.

Prior State Coverage in Minnesota and New York

In New York and Minnesota, state health programs predating the ACA made BHP a particularly appealing option. Before the ACA, both Minnesota and New York had health programs, funded in whole or in part by state dollars, that served much of the BHP-eligible population. These programs furnished more affordable and, in some cases, more comprehensive coverage than what federally subsidized qualified health plans (QHPs) offer in health insurance marketplaces under the ACA. BHP let states maintain such pre-ACA coverage while achieving fiscal gains by replacing state dollars with federal BHP funds.

Minnesota’s pre-existing coverage program, MinnesotaCare (MNCare), was originally created in 1992 to provide working people with access to affordable health coverage.1 By 2011, the program served children, parents, and pregnant women up to 275% FPL and childless adults with incomes up to 250% FPL through a Medicaid Section 1115 waiver.2 Prior to 2015 the program was funded by a state tax on medical providers and health plans (covering 48% of costs in 2012), federal medical assistance matching dollars (44%), and sliding-scale premiums paid by enrollees (8%).3 Anticipating a switch to BHP, the state authorized changes to the program in 2013. These changes included limiting adult’s eligibility to 200% FPL and adding lawfully present non-citizens with incomes below 138% FPL as well as eliminating asset limits and a cap on covered hospital services.4 BHP implementation meant that, instead of standard federal matching funds, the state would receive 95% of the amount that BHP consumers would otherwise have received in marketplace subsidies, which was expected to yield significant state budget savings.

New York provided state-funded coverage to lawfully present immigrants ineligible for federal Medicaid. The 2001 New York Court of Appeals decision in Aliessa v. Novello required the state to provide Medicaid to otherwise eligible lawfully present immigrants for whom the state was denied federal Medicaid funds. Some had been lawful residents for less than five years, others were Permanently Residing Under Color of Law in categories outside those qualifying for federal Medicaid funding.5 New York covered this population with state-only dollars before it implemented BHP. Following the implementation of BHP, the federal government, through BHP payments, assumed much of the cost of covering this population.6 These savings were anticipated to provide significant state budget gains even as BHP offered coverage substantially more affordable than subsidized QHPs to adults with incomes between 138% and 200% FPL.

Overview of BHP in Minnesota and New York

Minnesota was the first state to adopt the BHP. Minnesota converted MNCare to BHP effective January 1, 2015. The primary effect was financial—the source of federal funding shifted from Medicaid to BHP. Consumers were able to remain in the same plans and received the same benefits and cost-sharing protections as before. Regardless of the health plan they choose, MNCare enrollees pay premiums and cost-sharing on the same sliding scale, beginning at 35% FPL, and all enrollees receive the same benefits.

New York provided BHP, termed “the Essential Plan (EP),” to immigrants starting in April 2015, adding adults between 138-200% FPL effective January 1, 2016. New York offers four EP products—known as EPs 1, 2, 3, and 4. EP 1 and 2 are for those with incomes 151%-200% FPL (EP 1) and 139%-150% FPL (EP 2). EP 3 and 4 serve immigrants between 100-138% FPL (EP 3) and under 100% FPL (EP 4).7 Benefits and cost-sharing vary across the four EP categories, though within each category all health plans offer the same coverage at the same cost to consumers. For immigrants, the 2015 move to EP involved financial accounting, without affecting consumers’ coverage. In 2016, benefits and cost-sharing remained largely unchanged, but immigrants were moved from Medicaid to EP plans. In some cases, immigrants needed to choose a new health plan. Adults with incomes 138%-200% FPL who were previously enrolled in QHPs transitioned into EP during the 2016 open enrollment period (OEP).

Table 1 describes key aspects of BHP in each state.

| Table 1: Key BHP Features in Minnesota and New York | ||

| Minnesota (MinnesotaCare) | New York (Essential Plan) | |

| Overall Approach | ||

| Program Structure |

|

|

| Premiums, Cost-sharing, and Benefits | ||

| Premiums |

|

|

| Cost-sharing |

|

|

| Benefits |

|

|

| Enrollment/Disenrollment | ||

| Enrollment Policy |

|

|

| Grace Period |

|

|

| Health Plan Contracting | ||

| Approach to contracting |

|

|

| Health plan overlap |

|

|

| Provider networks |

|

|

| Program Administration | ||

| Administration |

|

|

| Financing | ||

| Costs |

|

|

| Source of funding |

|

|

Key Findings

Program Design

Premiums, Cost-Sharing, and Benefits

BHP programs in Minnesota and New York provide coverage without deductibles and with lower premiums than what consumers would pay for subsidized marketplace plans. In New York, EP premiums were set by the state legislature at $20 per individual for those with incomes above 150% FPL and at or below 200% FPL. Enrollees with incomes up to 150% FPL do not pay premiums.8 In contrast, enrollees in MNCare pay premiums on a sliding scale from 35% FPL to 200% FPL,9 except for specified exempt groups.10 In both states, BHP premium payments are less than what consumers would have paid for the second-lowest-cost silver plan in the marketplace (Table 2).11 BHP enrollees face no deductibles in either state. Although the Minnesota statute provides for a $2.95 monthly MNCare deductible, all BHP plans waive the deductible. Stakeholders noted that consumers greatly valued the absence of deductibles in both states’ BHP programs.

| Table 2: 2016 Monthly Premiums for BHP and QHPs | |||

| Income | MinnesotaCare | Essential Plan | QHP Benchmark Planwith Premium Tax Credits |

| 35% FPL | $4 | $0 | $7 |

| 140% FPL | $25 | $0 | $48 |

| 151% FPL | $37 | $20 | $61 |

| 200% FPL | $80 | $20 | $126 |

| SOURCE: Minnesota Department of Human Services, MinnesotaCare Premium Estimator Table, (Minnesota Department of Human Services, 2015); New York State of Health, Attachment F – BHP Product Offering and Cost-Sharing (New York State of Health, 2015); Kaiser Family Foundation, 2016 Health Insurance Marketplace Calculator (QHP premiums calculated based on US average premium for single-person household).NOTE: BHP is called “MinnesotaCare” and “Essential Plan” in Minnesota and New York, respectively. | |||

In New York, other BHP cost-sharing is also lower than for subsidized marketplace plans. EP plans 1 and 2 have actuarial values (AV) above 95% while EP plans 3 and 4 mirror cost-sharing in Medicaid. A plan’s AV is the percentage of the cost of covered services the plan is expected to pay on average for a typical group of enrollees. Thus, a higher AV plan will lower the share of costs borne by enrollees. Consumers with income at or below 250% FPL are eligible for cost-sharing reductions (CSR) in the marketplaces, which raise the AV of standard QHPs. However, BHP coverage in New York pays a higher proportion of out-of-pocket costs than QHPs with these CSRs. For consumers with incomes up to 150% FPL, QHPs with CSRs offer 94% AV, and for those with incomes between 151-200% FPL, QHPs with CSRs provide 87% AV. Stakeholders noted that when consumers with incomes between 138% and 200% FPL enrolled in New York QHPs, they were charged copayments above BHP levels for office visits, hospital utilization, and prescription drugs, and those with incomes between 150% and 200% FPL also faced $250 deductibles (Table 3). New York advocates pushed hard for low cost-sharing in BHP and were happy with the state’s decisions.

| Table 3: For New York Consumers Between 138-200% FPL, Cost-Sharing in BHP vs. QHPs with CSRs | ||||

| 138-150% FPL | 151-200% FPL | |||

| BHP | QHP with CSRs | BHP | QHP with CSRs | |

| Deductible (single) | $0 | $0 | $0 | $250 |

| Max out-of-pocket limit (single) | $200 | $1,000 | $2,000 | $2,000 |

| Copayments | ||||

| PCP | $0 | $10 | $15 | $15 (after deductible) |

| Specialist | $0 | $20 | $25 | $35 (after deductible) |

| Inpatient hospital | $0 | $100 per admission | $150 per admission | $250 per admission (after deductible) |

| ER Visit | $0 | $50 | $75 | $75 |

| Tier 1 drugs | $1 | $6 | $6 | $9 |

| Tier 2 drugs | $3 | $15 | $15 | $20 |

| Tier 3 drugs | $3 | $30 | $30 | $40 |

| SOURCE: 2017 Invitation for Participation in New York State of Health, Attachment F – BHP Product Offering and Cost-Sharing, NY State of Health, 2015.NOTE: New York refers to BHP as the “Essential Plan,” or EP. Cost-sharing and premiums vary between EP 1, which serves consumers between 151-200% FPL, and EP 2, which covers consumers at 138-150% FPL. QHPs with CSRs are from the 2015 New York marketplace. | ||||

Minnesota increased BHP premiums and cost-sharing in 2015, but the resulting amounts are still lower than what consumers would have faced in the marketplace. In 2015, the Minnesota legislature increased MNCare premiums for enrollees with incomes 150%-200% FPL. The amount of the increase was scaled to income, with a 28% rise for those with incomes between 150%-159% FPL increasing to a 60% boost for those with incomes at 200% FPL. However, as shown in Table 2, these amounts are still lower than the premiums consumers would have been charged in the marketplace for subsidized QHPs with benchmark premiums. The legislature also lowered the AV of MNCare plans from 98% to 94%, bringing cost-sharing in line with marketplace coverage for those with incomes at or below 150% FPL. The resulting cost-sharing remained under the amounts charged in the marketplace for those between 150% FPL and 200% FPL, who in non-BHP states are offered QHPs with 87% AV.12 Minnesota’s premium and cost-sharing increases went into effect in August 2015 and January 2016, respectively, and were expected to yield an estimated $27.8 million in additional revenue over 23 months.13

| Table 4: MinnesotaCare Premium and Cost-Sharing Changes | |||

| Cost-Sharing Changes | Through Dec. 31, 2015 | Effective Jan. 1, 2016 | |

| Deductible | $0 | $0 | |

| Nonpreventive office visits | $3 | $15 | |

| Mental health visits | $0 | $0 | |

| ER visits (does not apply if admitted) | $3.50 | $50 | |

| Inpatient hospital admission | $0 | $150 | |

| Prescription drugs (generic) | $3 | $6 | |

| Prescription drugs (brand name) | $3 | $20 | |

| Prescription drug OOP monthly maximum | None | $60 | |

| SOURCES: Minnesota Department of Human Services, Bulletin: Legislative Changes to Medical Assistance and MinnesotaCare, Minnesota Department of Human Services, July 2015, http://www.dhs.state.mn.us/main/groups/publications/documents/pub/dhs16_195870.pdfRandall Chun. MinnesotaCare Information Brief, Research Department of the Minnesota House of Representatives, updated January 2016, http://www.house.leg.state.mn.us/hrd/pubs/mncare.pdfNOTE: Minnesota statute provides for $2.95 monthly deductibles in MNCare, but all plans waive those deductibles. BHP is called “MinnesotaCare” in Minnesota. | |||

For many BHP enrollees, benefits are broader than with QHPs. MNCare consumers receive, in addition to what QHPs offer, oral health services, vision services, and enhanced behavioral health coverage. In New York, EP 1 and 2 offer the same benefits as QHPs. EP 3 and 4 approximate Medicaid benefits by covering non-prescription drugs, orthotic devices, orthopedic footwear, adult vision care, adult dental care, and non-emergency transportation (administered by the Department of Health), in addition to QHP services.14 EP 1 and 2 do not cover adult vision and dental care as part of the standard benefit package; to obtain those benefits, consumers must pay the additional premium from insurers that offer coverage for such services.15

Contracting with Health Plans

Most BHP insurers also participate in Medicaid and/or the marketplace. In both states, officials sought to have the same plans and provider networks available in Medicaid, BHP, and QHP. Such an overlap promotes continuity of care when consumers’ income changes and they move between programs. In Minnesota, the state conducted a joint procurement for Medicaid and BHP; plans wishing to join one program had to participate in both. In each county, consumers can choose between two or three Medicaid/MNCare plans, at least one of which also offers marketplace coverage.16 In New York, 13 insurers offer EP, 11 of which participate in all three programs.17 State officials reported that, in 2016, EP consumers have a choice of plans in all but two rural counties. For 2017, state officials indicated that all counties will have a choice of plans.

BHP health plan payments were based on Medicaid rates then adjusted for the BHP population. State officials in Minnesota reported that the capitation rates for Medicaid and MNCare were similar in 2016. However, the joint procurement for both programs included rebidding prior managed care contracts. By leveraging Medicaid participation, and because BHP enrollees proved healthier than the historical MNCare population, the state was able to negotiate MNCare capitation rates that were 15% lower than expected. In New York, the rates for EP 3 and 4 were set at the Medicaid rate, while rates for EP 1 and 2 were based on the Medicaid rates then adjusted to reflect differences between Medicaid and EP utilization patterns, covered benefits, and cost-sharing rules. These adjustments raised rates for EP 1 and 2 20% above Medicaid levels.

Provider Networks

In Minnesota, provider networks are broader in BHP than the marketplace; the picture is more varied in New York. According to state officials, despite lower provider payments in BHP than the marketplace, Minnesota’s BHP plans offered broader networks; BHP plans included all Medicaid providers, while QHPs used narrow networks to restrain premiums. The greater breadth of Medicaid/BHP networks over QHP networks was particularly significant with dental care, behavioral health care, and Mayo Clinic providers. In New York, the picture was more complex; some consumers who moved from QHPs to BHP lost access to previous providers. In most cases, New York insurers used their Medicaid provider networks for BHP; however, some insurers’ BHP networks were more limited than their Medicaid provider networks. A number of stakeholders saw this as a transitional effect that would likely diminish or disappear over time.

Having similar provider networks across the three coverage programs facilitated New York consumers’ transition to EP. Beginning in January 2016, consumers previously enrolled in QHPs were transitioned to new EP plans. State officials reported that consumers could automatically renew in “sister” EP plans, those that were offered by the same carrier and that had at least 85% of their providers participating in both plans. Consumers had the option to change insurers for the 2016 plan year, rather than auto-renew. Some consumers whose QHPs were not offered by an EP-participating carrier could not auto-enroll and had to affirmatively select an EP plan.

Impact on Consumers

BHP enrollment

Enrollment increased substantially following BHP implementation in New York. Implementation of EP in New York in 2016 provided a natural experiment testing the impact of increased affordability on enrollment. Among adults with incomes 150-200% FPL—all of whom moved from federally-subsidized QHPs to EP—enrollment grew by 42% between 2015 and the end of the 2016 open enrollment period (OEP), an increase of 52,000 enrollees. By contrast, enrollment increased by only 4% among adults with incomes 200-400% FPL, whose subsidy eligibility was unaffected by BHP implementation (Figure 1).18 Overall, enrollment among those with incomes from 138% – 200% FPL, who moved from the marketplace into BHP, rose 35% (from 166,000 to 224,000). Compared to those with incomes 150%-200% FPL, enrollment growth among BHP enrollees with incomes 138%-150% FPL was less pronounced. In 2015, nearly half of those in the latter group (19,000 out of 40,000) were parents who received supplemental state subsidies that paid the full QHP premium.19 As a result, the affordability improvements from moving to BHP were much lower in magnitude for many in this group than for those with incomes between 150%-200% FPL.

In New York, those eligible for BHP were more likely to enroll than those determined eligible for subsidized QHP coverage. Among people who applied for 2016 coverage and qualified for BHP in New York, 98% continued through the enrollment process to select a plan.20 Only 58% did so among applicants who were found eligible for subsidized and unsubsidized QHPs, combined.21 Stakeholders reported that BHP increased participation because of both reduced premiums and the absence of deductibles. Lower out-of-pocket cost-sharing in BHP also appeared to improve consumers’ receipt of primary care, according to some stakeholders. According to state analyses, consumers enrolled in BHP averaged $1,100 in savings compared to what they would have paid for subsidized QHP coverage.22 Similar estimates were not available for Minnesota.

Stakeholders reported that MNCare’s greater affordability increased enrollment. Minnesota did not offer a comparable natural experiment to New York, since eligibility for BHP and subsidized QHP coverage did not change from 2014 through 2016. However, stakeholders believed that BHP’s lower premiums and out-of-pocket cost-sharing, compared to subsidized QHP coverage, contributed to enrollment growth following ACA implementation. Monthly MNCare enrollment increased from 79,000 in September 2014 to nearly 101,000 in September 2016.23 State officials noted that enrollment dipped slightly from 2015 to 2016 as systems issues that had delayed the renewal process were resolved and those who were no longer eligible transitioned off coverage.

BHP enrollees were reportedly younger and healthier than those in QHPs. Although detailed data enabling a comparison of demographic characteristics were not publicly available, carriers in New York reportedly were pleased that younger and healthier members signed up for EP, though officials noted that one year’s experience is a limited basis for generalization. Minnesota officials described BHP members as younger and healthier than both the Medicaid population and QHP enrollees. Officials in both states attributed these effects to the greater affordability of BHP compared to subsidized marketplace coverage.

Year-round BHP enrollment improved consumers’ access to coverage without harming the risk pool. Because of BHPs’ low premiums, stakeholders observed that consumers had little or no incentive to delay enrollment until illness or injury created a need for coverage. Carriers in both states thus report that year-round enrollment has not led to detectable adverse selection. The impact of year-round enrollment on total coverage levels may be significant. For example, New York State officials project that, between the end of the 2016 OEP and 2017, BHP enrollment will grow from nearly 380,000 to roughly 600,000.

Stakeholders reported that consumers valued the increased predictability and simplicity of BHP coverage, compared to marketplace plans. According to consumer groups and enrollment assisters, consumers appreciated the greater predictability and understandability of premiums, cost-sharing, plan networks, and benefits offered by BHP’s state-defined coverage, which remained constant from plan to plan. Consumers had no need to reengage with a rapidly changing and complex marketplace at open enrollment each year. That said, changes occur in state-administered systems, as illustrated by Minnesota’s increases in 2016 premiums and cost-sharing.24 Stakeholders noted that while some consumers complained about these changes, particularly increased out-of-pocket costs, coverage remained relatively affordable and understandable; enrollment thus did not decline.

Coverage Transitions

The two states varied in the integration of their eligibility systems. In both New York and Minnesota, the marketplace provides an online enrollment pathway for Medicaid, CHIP, BHP, and the marketplace. New York’s system determines eligibility for all programs and lets consumers complete the enrollment process online, preventing breaks in coverage both following the initial application and when consumers move between programs. However, a few thousand immigrants who were still in the state’s “legacy” Medicaid system had to be transferred manually. Minnesota’s marketplace system also provides eligibility determinations for Medicaid and MNCare; however, if verification or further follow-up is needed, the application is sent to counties to complete Medicaid enrollment or the state Department of Human Services (DHS) to complete MNCare enrollment. Stakeholders expressed concern that breakdowns can occur with the information transfer, leading to enrollment delays for some consumers and the possibility of some consumers not getting coverage. They noted that problems and delays are more likely to occur for families in which some members are eligible for Medicaid and others qualify for MNCare.

BHP enrollees whose incomes rise above 200% FPL experience steep cost increases when they move to QHPs. In federally subsidized QHPs, these enrollees face both higher premiums and higher cost-sharing, including deductibles, which BHP plans do not charge. Compared to Minnesota, the cliff is steeper in New York because BHP coverage is less costly to consumers; but in both states, stakeholders indicated that the combination of higher premiums along with deductibles of $1,500 or more for consumers moving into QHPs poses real financial challenges. They further noted that the cliff existed prior to BHP implementation when consumers moved from Medicaid to QHP coverage; however, it was not as steep because the marketplace subsidies are more generous at 139% FPL than 200% FPL. While stakeholders expressed concern over this cliff, they felt that this highlighted the importance of BHP as a more affordable coverage option.

Minnesota is exploring ways to expand BHP coverage beyond the current eligibility levels. To address affordability concerns above 200% FPL and to lessen the severity of the current “cliff,” a multi-stakeholder task force in Minnesota recommended expanding BHP to 275% FPL. Advocates in New York have called for a similar discussion of options to improve affordability for higher income marketplace enrollees.

Impact on the Marketplace

BHP did not appear to harm administrative funding for marketplaces. In Minnesota, financing for the state’s marketplace, MNsure, comes from a 3.5% assessment on QHP premiums sold through the marketplace.25 By covering consumers with incomes under 200% FPL who would have otherwise enrolled in the marketplace, BHP reduced this assessment revenue. However, Minnesota applies standard federal cost-allocation principles to marketplace activities, including eligibility determination, application assistance, and public education, that benefit Medicaid and BHP. As a result, MNsure receives payments from DHS to support marketplace operations. State officials reported that these cost-allocation payments for Medicaid and BHP consumers provided the marketplace with adequate and stable administrative funding. New York finances its marketplace through a broad-based assessment on plans inside and outside the marketplace. Consequently, adopting the BHP did not affect New York marketplace revenues.

BHP did not appear to affect marketplace stability. In New York, officials who worried about marketplace effects before program implementation reported that, after implementation, those worries proved unwarranted as marketplace stability remained unaffected. In Minnesota, the marketplace has experienced significant upheaval, with many carriers reporting losses, some high-profile plan exits, and significant premium increases (particularly for 2017). State officials and most stakeholders believed that BHP was not responsible for those problems. They attributed the marketplace’s challenges to carriers’ initial underpricing of QHP premiums; the state’s high-risk pool ending in 2015, which shifted many high-cost consumers to QHPs; federal underfunding of risk-corridor payments; and other causes unrelated to BHP. However, carriers suggested that the reduced size of the marketplace due to BHP may have made its risk pool more vulnerable to enrollment by relatively few high-cost consumers. In New York and Minnesota, BHP had a minimal impact on overall risk levels and premiums in the individual market, according to officials.

Impact on State Administration and Financing

BHP Administration

Existing state agencies administer BHP in both states. In both New York and Minnesota, the Medicaid program assumes most administrative responsibilities for BHP, with the marketplace taking on some tasks. According to stakeholders, because MNCare was once a Medicaid waiver program, the Medicaid agency assumes overall programmatic responsibility for BHP. In New York responsibilities are shared between Medicaid and the marketplace, both of which are housed in the state’s Department of Health. For example, Minnesota’s Medicaid agency both contracts with BHP plans and sets BHP rates; and in New York the marketplace contracts with plans, while the Medicaid program sets payment rates. Relying on existing infrastructure for BHP administration reduced administrative costs. Stakeholders in New York also noted that using existing agencies helped create a smoother launch with BHP than had been observed with other new health programs. According to stakeholders, neither state covered BHP administrative costs through premium assessments on BHP plans. Based on guidance from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, such assessments can be funded through federal BHP allotments, since fees and taxes are absorbed into BHP premiums.26

Coordination among state agencies is generally effective in both states, though there have been some challenges. Given the shared responsibilities for BHP program administration between Medicaid and the marketplaces, stakeholders noted that strong communication and coordination between the agencies was essential. Officials in both states reported having good working relationships with their sister agencies and felt the administrative structure supported effective program administration. Operationally, stakeholders in Minnesota noted some challenges related to the state’s multiple eligibility systems. They felt that better coordination around business processes might help to lessen enrollment delays some consumers face as they move between programs.

BHP Costs and Financing

The study states achieved significant savings by moving individuals from older coverage programs into BHP. According to state officials, New York saved an estimated $1 billion in state fiscal year (SFY) 2016 by using federally-funded BHP to cover approximately 250,000 lawfully present immigrants who had previously received state-funded Medicaid. Even though the state incurred new costs for non-immigrant BHP enrollees, the state still realized more than $800 million in net savings. Minnesota likewise anticipated fiscal gains from transitioning consumers out of a Medicaid waiver program, for which the state paid nearly 50% of all costs, into BHP. However, the state did not experience anticipated financial relief in 2015. Federal BHP payments are based on QHP premium levels, and the state’s unexpectedly low initial QHP premiums reduced 2015 federal BHP funding below projected levels. Higher QHP premiums in 2016 increased federal BHP funding. In addition, legislatively-mandated increases in premium and cost-sharing requirements along with a healthier-than-expected BHP population, both of which are discussed above, lowered BHP program expenditures. As a result of these combined factors, Minnesota’s BHP provided budget gains in 2016 that were greater than originally anticipated.

State contributions are required to cover a portion of BHP costs in both states. For several reasons, including federal BHP payments provide only 95% of what the federal government would have spent on subsidies had BHP enrollees received marketplace coverage; BHP coverage in both Minnesota and New York is more generous than federally-subsidized QHP coverage; and BHP pays plans more than Medicaid, federal financing does not fully cover BHP program costs. In New York, projected EP costs for FY 2017 are $2,461 million. Federal BHP payments are expected to pay 85% of the costs, and state general operating funds will cover 15%, or $377 million.27 In Minnesota, projected costs for MNCare for FY 2017 are $608 million. Federal BHP payments are projected to cover 68% of these costs; consumer premium contributions will finance 7%; and the state will contribute 26% (Figure 2).28 Stakeholders in Minnesota expressed concern about future funding for BHP. The state relies on a 2% provider tax to finance BHP, among other programs. Originally, the provider tax paid many costs, such as for the state’s high-risk pool, that are no longer needed following ACA implementation. In 2014, the state legislature repealed the provider tax effective December 2019, but did not establish an alternative financing mechanism for BHP. While near-term funding will be available, and BHP enjoys widespread support among policymakers and stakeholders, the long-term implications for the program are unclear. Stakeholders in both Minnesota and New York believed that stable funding sources for both the marketplace and BHP were critical to ensuring the programs’ future. An important open question is how much the rise in QHP premiums for 2017 and beyond, which will increase federal BHP payments, will lower state BHP costs.

Lessons Learned

Following the outcome of the 2016 elections, the future of BHP and other Affordable Care Act provisions is unclear. Despite this uncertainty, the experiences of Minnesota and New York with BHP suggest broader lessons about effective coverage programs for low-income consumers.

Substantial enrollment gains and an improved risk pool can result when low-income consumers are offered coverage much more affordable than federally subsidized marketplace plans. New York’s “natural experiment” with BHP demonstrates the significant enrollment gains, including among the relatively young and healthy, that can be achieved by reducing this group’s premiums below subsidized QHP levels and eliminating deductibles.

Many consumers preferred the stability and simplicity of state-defined coverage to the marketplace’s complexity and unpredictability. Stakeholders reported that many low-income consumers found marketplace coverage confusing and hard to negotiate, preferring the consistency of state-administered coverage in which premiums, cost-sharing, and benefits were the same across participating plans. Consumers likewise appreciated the ability to stay in the same BHP plan without the need to “shop” each year to avoid large premium increases.

Encouraging plans and providers to participate across all coverage programs can promote continuity of care. Overlap of plans and networks promotes continuity of provider relationships and care when consumers move between programs because of changing household circumstances. In addition, Minnesota found that conducting joint procurement for Medicaid and BHP achieved savings in both public programs, broadened BHP provider networks beyond QHP levels, and increased the state’s leverage to implement delivery-system and payment reforms.

Relying on existing infrastructure to administer new coverage programs can create efficiencies and avoid duplication. Both Minnesota and New York administered BHP primarily through the Medicaid agency, thereby lowering BHP administrative costs. Neither state created new administrative structures to run BHP.

Conclusion

When federal officials announced that regulatory delays prevented states from implementing BHP until 2015, all states considering BHP put that option aside, except for Minnesota and New York. The latter states’ experiences highlight the potential for BHP to make coverage more affordable for those with incomes between 138-200% FPL. Both states set premiums and cost-sharing levels below those in the marketplace. Significant enrollment gains resulted when New York transitioned consumers from subsidized QHPs to BHP. Moreover, notwithstanding marketplace instability in Minnesota that most observers attribute to other factors, BHP does not appear to be a major factor undermining marketplace viability in either state.

Although the 2016 election results create uncertainty around the future of the ACA (including BHP), BHP implementation provides important lessons about structuring coverage programs for low-income uninsured consumers for consideration in future reforms. Significant enrollment gains and risk-pool improvements can result when low-income consumers are offered insurance that is substantially more affordable than federally subsidized marketplace coverage. Moreover, many consumers prefer the simplicity and predictability of a state-administered program, with uniform costs and benefits, to the changing, complex coverage offered in a health insurance marketplace.

Endnotes

- Minnesota Budget Project, Basic Health Plan Offers a Chance to Provide Comprehensive Health Care Coverage for Low-Income Minnesotans (St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Budget Project, January 2012), http://www.mnbudgetproject.org/research-analysis/economic-security/basic-health-plan ↩︎

- Minnesota Department of Health Services, Prepaid Medical Assistance Project Plus (PMAP+) Section 1115 Waiver Evaluation Plan 2014 (Minnesota Department of Health Services, 2014), http://dhs.state.mn.us/main/groups/healthcare/documents/pub/dhs16_194875.pdf ↩︎

- Editorial Board, “A next-generation model for MinnesotaCare,” Star Tribune, (May 2013), http://www.startribune.com/a-next-generation-model-for-minnesotacare/208894751/ ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- New York State of Health. NY State of Health Essential Plan Webinar, (New York State of Health, November 16, 2015), http://info.nystateofhealth.ny.gov/sites/default/files/Essential%20Plan,%2010-7-15.pdf ↩︎

- “State Moves Forward with BHPs,” Greater New York Hospital Association, (August 2015), http://www.gnyha.org/PressRoom/Publication/f4baa92a-cec4-4f90-a945-c6e2aa2f6198/ ↩︎

- New York requires insurers to follow the BHP naming convention in naming their products to ensure that consumers can easily identify BHP plans. “Essential Plan 1” is the product for individuals with incomes between 150 and 200% FPL, “Essential Plan 2” is the product for individuals with incomes between 138 and 150% FPL, “Essential Plan 3” is the product for individuals with incomes between 100 and 138% FPL who are not eligible for Medicaid due to immigration status, and “Essential Plan 4” is the product for individuals with incomes at or below 100% FPL who are not eligible for Medicaid due to immigration status. ↩︎

- 2017 Invitation for Participation in New York State of Health, Attachment F – BHP Product Offering and Cost-Sharing (New York State of Health, 2015), http://info.nystateofhealth.ny.gov/sites/default/files/Attachment%20F%20-%20BHP%20-%20Benefits%20and%20Cost-Sharing,%205-15-15.pdf ↩︎

- Minnesota Department of Human Services, MinnesotaCare Premium Estimator Table, (Minnesota Department of Human Services, 2015), https://edocs.dhs.state.mn.us/lfserver/Public/DHS-4139A-ENG ↩︎

- Individuals under age 21, American Indians and Alaska Natives and their family members are exempt from premiums, and members of the military who have completed a tour of active duty within 24 months and their family members are exempt from premiums for 12 months. Medicaid.gov, Minnesota’s Basic Health Program Blueprint, (Medicaid.gov, April 2016), https://www.medicaid.gov/basic-health-program/downloads/minnesota-bhp-blueprint.pdf ↩︎

- Because neither Minnesota nor New York enrolled BHP individuals into the marketplace in 2016, a direct comparison of what those individuals would have paid in premiums is not possible. The estimates included in the Table are based on a household size of 1. While the estimates were calculated based on the US average premium for a single adult age 40, the actual consumer costs at the applicable income levels are based entirely on family income when consumers purchase benchmark-priced coverage. Source: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2016 Health Insurance Marketplace Calculator, https://modern.kff.org/interactive/subsidy-calculator-2016/ ↩︎

- Randall Chun, MinnesotaCare Information Brief, (St. Paul, MN: Research Department of the Minnesota House of Representatives, January 2016), http://www.house.leg.state.mn.us/hrd/pubs/mncare.pdf ↩︎

- Minnesota Department of Human Services, Bulletin: Legislative Changes to Medical Assistance and MinnesotaCare, Minnesota Department of Human Services, July 2015, http://www.dhs.state.mn.us/main/groups/publications/documents/pub/dhs16_195870.pdf ↩︎

- New York State of Health, Invitation and Requirements for Insurer Certification and Recertification for Participation in 2016 (NY State of Health, May 2015), http://info.nystateofhealth.ny.gov/sites/default/files/2016%20Invitation%20to%20Participate%20in%20NYSOH%2C%205-15-15.pdf ↩︎

- New York State of Health, Invitation and Requirements for Insurer Certification and Recertification for Participation in 2016 (NY State of Health, May 2015), http://info.nystateofhealth.ny.gov/sites/default/files/2016%20Invitation%20to%20Participate%20in%20NYSOH%2C%205-15-15.pdf ↩︎

- Minnesota Department of Human Services, MinnesotaCare Health Plan Choices by County (Minnesota Department of Human Services, January 2016) https://edocs.dhs.state.mn.us/lfserver/Public/DHS-4326-ENG ↩︎

- The NY State of Health: Official Health Plan Marketplace, 2016 Open Enrollment Report, (August 2016) http://info.nystateofhealth.ny.gov/sites/default/files/NYSOH%202016%20Open%20Enrollment%20Report%282%29.pdf ↩︎

- Authors’ calculations, The NY State of Health: Official Health Plan Marketplace, 2016 Open Enrollment Report, (August 2016) http://info.nystateofhealth.ny.gov/sites/default/files/NYSOH%202016%20Open%20Enrollment%20Report%282%29.pdf; The NY State of Health: Official Health Plan Marketplace, 2015 Open Enrollment Report, (July 2015), http://info.nystateofhealth.ny.gov/sites/default/files/2015%20NYSOH%20Open%20Enrollment%20Report.pdf ↩︎

- Peter Newell and Nikhita Thaper. New York’s Temporary Premium Subsidies: Meeting Immediate Goals and Yielding Useful Lessons. United Health Fund, June 2016. https://www.uhfnyc.org/assets/1492 ↩︎

- The NY State of Health: Official Health Plan Marketplace, 2016 Open Enrollment Report, (August 2016), http://info.nystateofhealth.ny.gov/sites/default/files/NYSOH%202016%20Open%20Enrollment%20Report%282%29.pdf ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Minnesota Department of Human Services, Managed care enrollment figures, available at: http://www.dhs.state.mn.us/main/idcplg?IdcService=GET_DYNAMIC_CONVERSION&RevisionSelectionMethod=LatestReleased&dDocName=dhs16_141529#. ↩︎

- Randall Chun, MinnesotaCare Information Brief, (St. Paul, MN: Research Department of the Minnesota House of Representatives, January 2016), http://www.house.leg.state.mn.us/hrd/pubs/mncare.pdf ↩︎

- MNsure, MNsure FY 2017 Preliminary Budget—Explanation of Funding Sources and Expenditures, (St. Paul, MN: MNsure, March 2016), https://www.leg.state.mn.us/docs/2016/mandated/160417.pdf ↩︎

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. “Basic Health Program: State Administration of Basic Health Programs; Eligibility and Enrollment in Standard Health Plans; Essential Health Benefits in Standard Health Plans; Performance Standards for Basic Health Programs; Premium and Cost Sharing for Basic Health Programs; Federal Funding Process; Trust Fund and Financial Integrity.” Federal Register. Vol. 79, No. 48 (March 12, 2014): 14112-14151 at 14133, http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2014-03-12/pdf/2014-05299.pdf, as discussed in Stan Dorn and Jennifer Tolbert, The ACA’s Basic Health Program Option: Federal Requirements and State Trade-Offs, (Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured and the Urban Institute, November 2014), https://modern.kff.org/health-reform/report/the-acas-basic-health-program-option-federal-requirements-and-state-trade-offs/ ↩︎

- Andrew M. Cuomo and Robert F. Mujica Jr., FY 2017 Enacted Budget Financial Plan, (New York State of Opportunity, May 2016) https://www.budget.ny.gov/budgetFP/FY2017FP.pdf. ↩︎

- Minnesota Management and Budget, Health Care Access Fund, February 2016 Forecast Update, (Minnesota Management and Budget, February 2016), https://mn.gov/mmb/assets/feb16fcst-hcaf_tcm1059-157696.pdf ↩︎