How Affordable are 2019 ACA Premiums for Middle-Income People?

The majority of enrollees who purchase health coverage through Affordable Care Act (ACA) exchanges receive premium tax credits to help them afford their monthly premiums. To a large extent, subsidized enrollees are shielded from premium increases because their subsidies rise along with premiums. On the other hand, middle-income people with incomes above 400% of the Federal Poverty Line (“FPL”, equal to $48,560 for an individual and $100,400 for a family of four in 2019) are not eligible for subsidies and may struggle to afford ACA-compliant plans.

Marketplace enrollment among subsidized enrollees rose from 8.7 million in 2015 to 9.2 million in 2018. However, premiums increased significantly, and the number of unsubsidized enrollees in ACA-compliant plans has fallen over this same period from 6.4 million to 3.9 million. Unlike subsidized enrollees, those with incomes over 400% of poverty have to bear the full cost of premium increases if they buy an ACA-compliant plan.1

While premiums for ACA Marketplace plans are holding steady or falling slightly on average in 2019, whether ACA plan premiums are actually affordable for an individual depends on where they live, how old they are, and how much money they make. We analyzed 2019 premiums data to show how affordable the lowest-cost ACA Marketplace plan is in each county, by age and income, with a focus on middle-class people whose incomes are too high to qualify for subsidies.

This brief finds that affordability challenges are particularly acute for older adults with incomes just above the premium subsidy cutoff (400% of poverty), particularly in rural areas where premiums are highest.

Figure 1

Most unsubsidized enrollees who enroll in ACA-compliant plans do so outside of the Marketplace. This brief only includes premiums for plans that are available on the Marketplace, but bronze premiums for people who are not eligible for subsidies are generally similar whether an enrollee buys through the Marketplace or not. (In all but 14 counties, the lowest-cost plan available is a bronze plan.)

The interactive map shows a substantial decline in affordability between a $45,000 income (which would put an individual at 371% of the poverty level and make them eligible for subsidies) and $50,000 (412% of poverty and therefore not eligible for subsidies). This phenomenon is referred to as the “subsidy cliff” because subsidy eligibility ends sharply at 400% of poverty without a phase-out, even if premiums represent a substantial share of income for those above 400% of poverty.

In 21% of counties, a 40-year-old making $50,000 would have to pay more than 10% of their income for the lowest-cost plan in the Marketplace. However, because premiums are lower in urban areas than in rural areas, just 8% of Marketplace enrollees are in a county where that would be the case. In 25% of non-metropolitan counties (weighted by enrollment), a 40-year-old making $50,000 would spend more than 10% of their income on premiums for the cheapest plan available, compared with only 5% of people in metropolitan counties.2

Rhode Island has the lowest average premiums for middle-class people ineligible for subsidies in 2019: a 40-year-old making $50,000 would pay about 5% of their income in premiums for the cheapest plan, on average. Wyoming has the highest average premiums for unsubsidized people: a 40-year-old making $50,000 would pay about 14% of their income in premiums for the cheapest plan, on average, with Nebraska and West Virginia in a close second and third place.

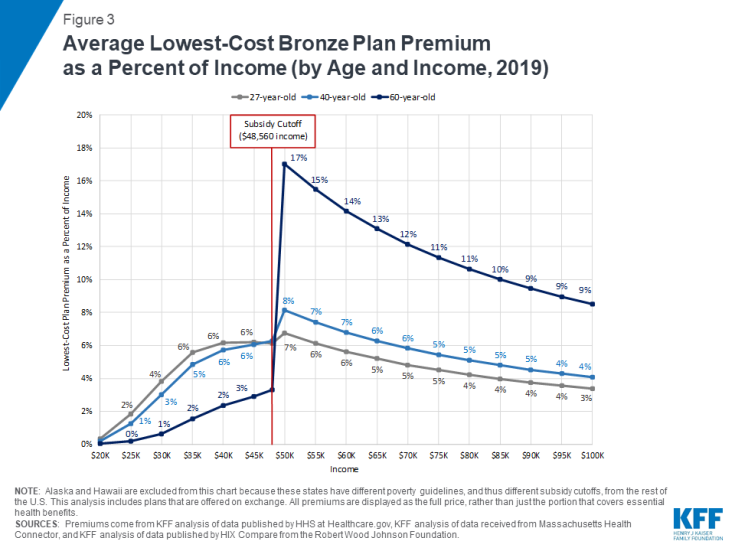

Figure 2 presents an interactive chart showing how much the national average premiums for a low-cost plan vary as a share of income at different income levels for people at various ages. (Figure 3 presents similar results as a static chart.) On average across the U.S., a 40-year-old making $45,000 would pay $227 a month (6% of their income) for a subsidized bronze exchange plan, whereas the same person making $50,000 would pay $340 a month (8% of their income) for the same plan without a subsidy. Because the ACA allows premiums for older adults to be three times those for younger enrollees, middle-class older people with unsubsidized coverage are the most likely to face affordability challenges. For example, a 27-year-old making $50,000 would pay 7% of their income in premiums for the average lowest-cost plan nationally, whereas a 60-year-old making the same income would pay 17% of their income in premiums. Even at an income of $70,000 (577% of the poverty level), a 60-year-old would have to pay 12% of income for a low-cost plan on average.

Figure 2: Average Lowest-Cost Plan Premium (by Income, Age, and Metal Level, 2019)

The premiums in this analysis are for the lowest-cost plan available in each county, but these low-cost bronze plans come with higher deductibles, copayments, or coinsurance than plans at higher metal tiers with higher monthly premiums. The average deductible for bronze plans in 2019 is $6,258, compared to $4,375 for silver plans (for people who do not receive cost-sharing subsidies because their incomes are above 250% FPL). While some services, including preventative care and often a few physician visits, are covered before enrollees reach their deductible, sicker enrollees may be better off choosing a silver or gold plan even if that means they spend a larger proportion of their income on premiums.

Discussion

After several years of rising ACA plan premiums, premiums are falling in many parts of the country for 2019. Despite this trend, premiums for even the cheapest exchange plans are still out of reach for many middle class people who are not eligible for ACA subsidies, particularly those who are older or live in high-premium areas. Several policy options have been proposed to address affordability for people buying their own coverage without a subsidy, such as expanding more loosely regulated short-term plans, creating state-based reinsurance programs, extending subsidies beyond 400% of poverty, and expanding eligibility for Medicaid or Medicare.

The Trump administration recently made changes to short-term, limited duration plans, with the goal of creating a more affordable option for people who are not eligible for subsidies. Short-term plans generally have significantly lower premiums than ACA-compliant coverage, in large part because these plans can exclude people with pre-existing conditions and may not cover certain services. Thus, while short-term plans come with lower premiums, these plans are generally not an option for people who have pre-existing conditions or expect to need high-cost services (e.g. for pregnancy, prescription drugs, or mental health care). Additionally, these plans will disproportionately attract healthy individuals away from ACA-compliant coverage, thus having an upward effect on premiums in the ACA-compliant individual market and possibly making unsubsidized coverage less affordable for people with pre-existing conditions.

The ACA established a temporary reinsurance program from 2014 to 2016 with the goal of making premiums more affordable during the early years of new market reforms. Reinsurance covers a portion of the health care expenses for high-cost patients, allowing insurers to reduce premiums.

Seven states (Alaska, Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, New Jersey, Oregon, and Wisconsin) have since created their own reinsurance programs, and initial evidence indicates that these programs have been successful in reducing individual market premiums, although the details of these plans vary widely between states. How much a reinsurance program can reduce premiums depends on the level of funding dedicated to it. Reinsurance reduces premiums somewhat for all enrollees ineligible for premium subsidies. However, this reduction in prices will not be enough to make plans affordable for all unsubsidized middle class people, particularly those facing the highest premiums as a share of income. For example, the cheapest plan in Natrona County, Wyoming costs $1,237 a month for an unsubsidized 60-year-old (25% of income for someone making $60,000). If the implementation of a reinsurance plan reduced all premiums by 10%, the cheapest plan would cost $1,113 (22% of income), which is still too expensive for many people to afford.

Expanding premium tax credits to enrollees over 400% of poverty would provide more significant assistance to those newly eligible for subsidies. For example, California Governor Newsom recently proposed expanding premium tax credits to incomes between 400 and 600% of poverty (incomes up to $72,840 for an individual).

Avoiding a subsidy cliff altogether would cost taxpayers more. One federal bill introduced in the House last year would extend premium subsidies to enrollees in all income brackets, and increase the amount of subsidies across the board. On average nationally, tax credits would need to extend to nearly 800% FPL to bring 2019 bronze premium payments down to 10% of income for a single 64-year-old, or just over 1,100% FPL to accomplish the same for silver premiums. In the 28 Nebraska counties with the most expensive 2019 premiums in the U.S., tax credits would need to extend beyond 1,400% FPL to bring bronze premium payments down to 10% of income for a single 64-year-old, or over 2,000% FPL to accomplish the same for silver premiums. In the case of an older couple living in a high-premium county, subsidies would need to extend beyond 3,000% FPL (a $500,000 income), for 2019 silver premiums to cost less than 10% of their income.

In late 2018, the Trump administration released new guidance and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued a discussion paper on Section 1332 waivers established by the ACA. This new guidance may prompt states to apply subsidies to ACA non-compliant plans or experiment with different subsidy structures, such as tax credits based on age and not income. One of the CMS waiver concepts describes extending subsidies to higher-income residents to address the “subsidy cliff.” Under a budget neutral waiver, however, increasing subsidy resources for one population group would necessitate reducing subsidy dollars available to other groups. Currently, ACA subsidies are structured so that lower-income enrollees pay a smaller percentage of their income (2% premium cap for those 100-133% of poverty) than higher-income enrollees (10% for those 300-400% of poverty), and they receive the bulk of subsidies. Additionally, as noted above, subsidies would need to extend well beyond 400% FPL to do away with the subsidy cliff altogether.

A number of recent congressional proposals would provide lower premium options to middle-class people buying their own coverage by expanding access to public programs like Medicare and Medicaid. For example, one bill would allow people age 50 and over to buy into Medicare, potentially lowering premiums through reduced prices paid to health care providers and curtailing administrative costs and profits. Another bill would allow states to set up programs that allow people to buy into the Medicaid program, capping premiums at 9.5% of income.

So far, while there seems to be a consensus that individual market premiums are out of reach for some middle-class people ineligible for ACA subsidies, there is little consensus around what to do about it.