Health Coverage and Care in the South in 2014 and Beyond

Health Coverage in the South in 2014

The Impact of the Affordable Care Act Coverage Expansions

A key goal of the ACA is to reduce the number of uninsured individuals through the creation of new coverage options that will allow individuals to access needed health care services. The ACA established a continuum of new coverage options including an expansion of Medicaid eligibility to nearly all adults with incomes at or below 138% FPL ($16,105 for an individual or $27,310 for a family of three in 2014) and the creation of Health Insurance Marketplaces with premium tax credit subsidies to help individuals with incomes up to 400% FPL ($46,680 for an individual or $79,160 for a family of three in 2014) purchase coverage. The ACA also includes provisions designed to provide consumers a streamlined, coordinated enrollment experience across health coverage programs. The combined effects of the coverage expansions, streamlined enrollment system, and broad outreach and enrollment efforts are expected to bring many uninsured individuals into coverage.

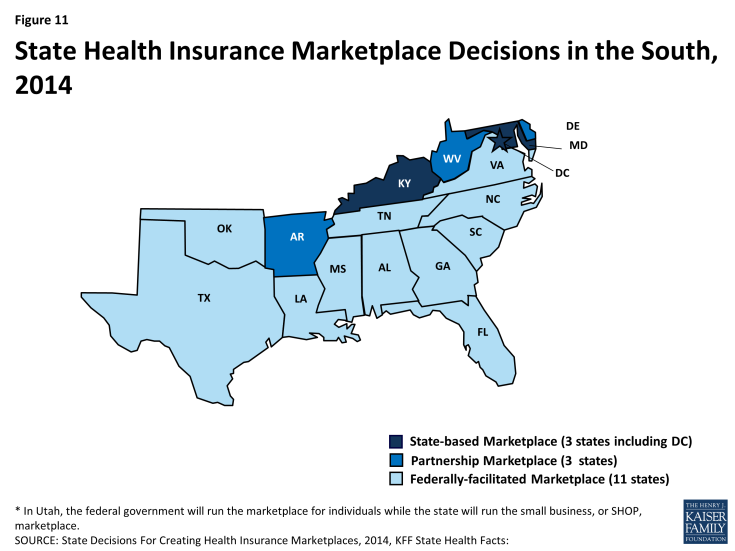

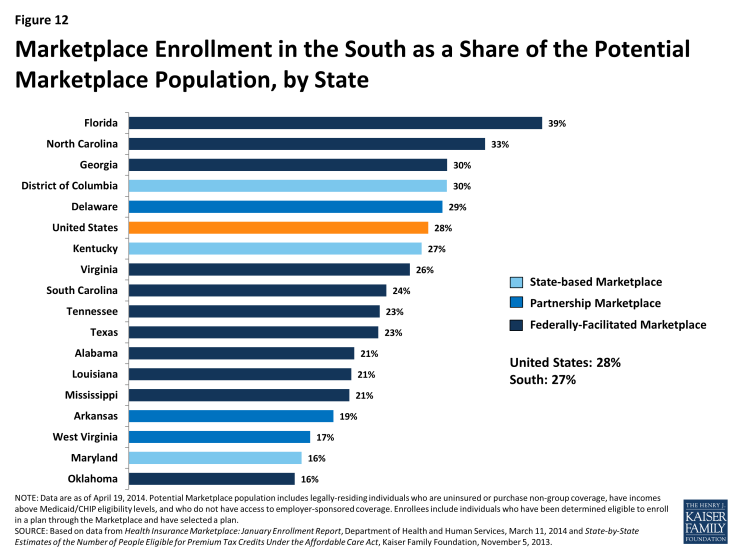

The majority of southern states (11 of 17) are relying on the Federally-facilitated Marketplace in 2014, although three (DC, KY, and MD) elected to establish their own State-based Marketplaces. Three additional southern states (AR, DE, and WV) are operating a Marketplace in partnership with the federal government (Figure 11). Marketplace enrollment varies across the southern states. As of April 19, 2014, after the initial annual open enrollment period, nearly 3.5 million Southerners had enrolled health coverage through a Marketplace– about 27% of the potential Marketplace population in the region.1 However, enrollment varied significantly by state, from 16% of the eligible population in Oklahoma to 39% of potential enrollees in Florida (Figure 12).

Figure 12: Marketplace Enrollment in the South as a Share of the Potential Marketplace Population, by State

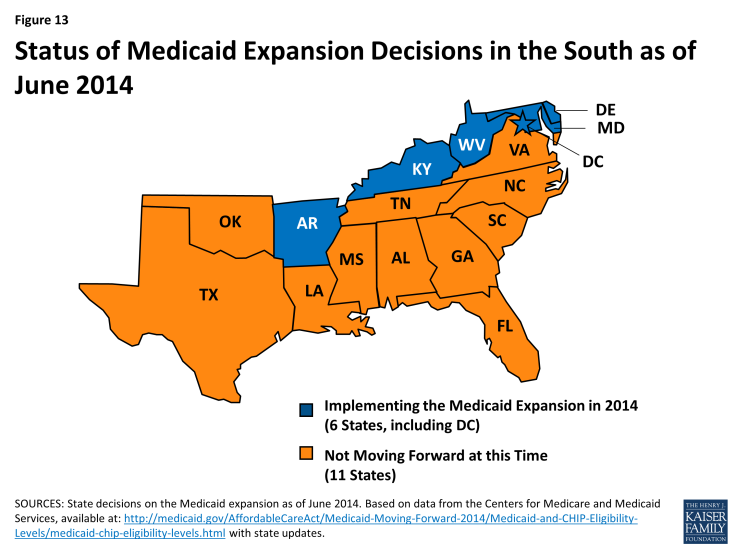

The ACA offers the potential to significantly increase coverage in the South, especially for low-income adults, but gaps in coverage will remain, as many southern states are not implementing the Medicaid expansion. As enacted, the Medicaid expansion was to apply to all states, setting a national income floor of 138% FPL for all adults, but the Supreme Court ruling on the ACA effectively made the expansion a state option. Just over half of the states (27 states, including DC), including 6 of the 17 Southern states, are implementing the expansion in 2014 (Figure 13).2 There is no deadline by which states must implement the Medicaid expansion, so additional states may choose to expand in the future.

Overall, southern states experienced a 7% increase in Medicaid enrollment in April 2014, compared to the monthly average in the states during the three months prior to open enrollment. This was similar to enrollment growth in the Northeast (7%) and Midwest (8%), but much lower than the Medicaid enrollment growth rate in the West during the same period (19%). The six southern states that are implementing the Medicaid expansion experienced much higher enrollment growth compared to states that are not expanding (26% vs. 4%). However, some southern non-expansion states experienced notable growth, including South Carolina, where Medicaid enrollment increased by 14% between Summer 2013 and April 2014.3

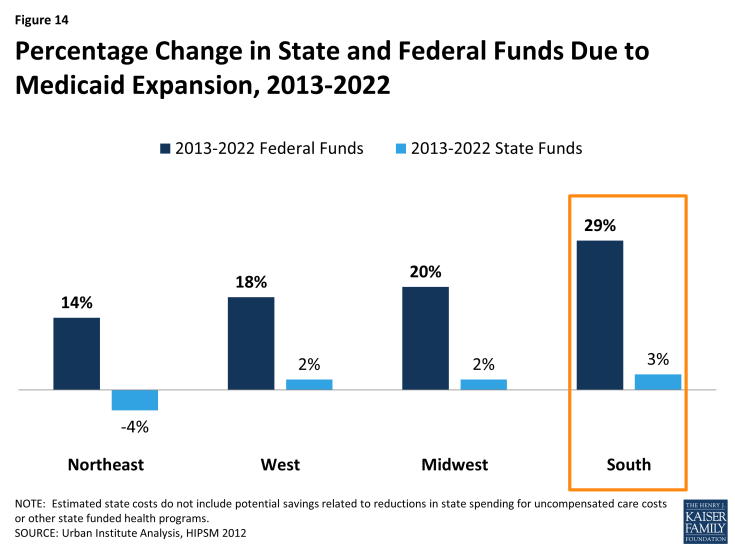

State Medicaid expansion decisions have significant fiscal implications for state spending on uncompensated care costs and indigent care programs, state economies, and for providers.4 If all states expanded Medicaid, southern states could experience the largest percentage increase in federal funds with the Medicaid expansion, compared to states in other regions (Figure 14).

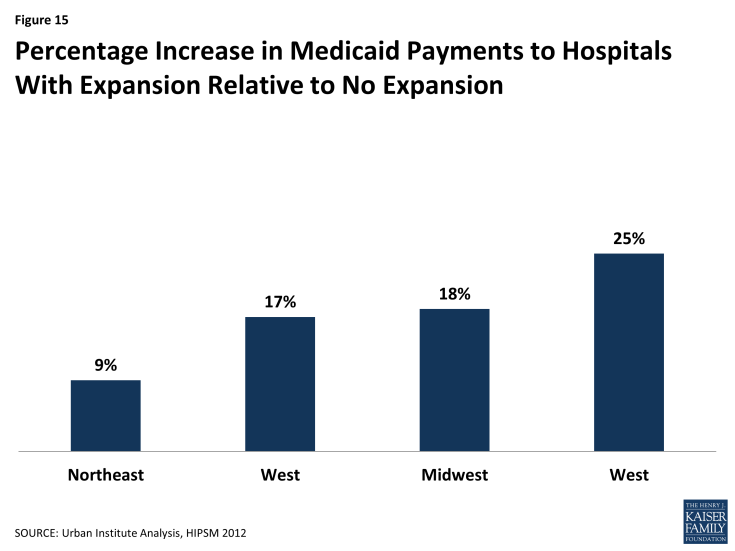

If all states expanded Medicaid, southern states could also experience a 25 percent increase in Medicaid payments to hospitals relative to no expansion – the highest percentage increase of any region (Figure 15).

Figure 15: Percentage Increase in Medicaid Payments to Hospitals With Expansion Relative to No Expansion

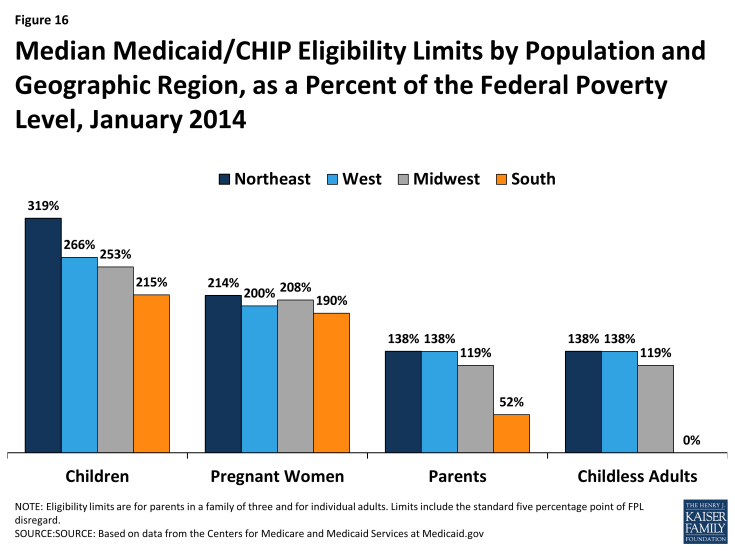

Without the Medicaid expansion, Medicaid eligibility for adults remains very limited in the South. The ACA Medicaid expansion was designed to fill longstanding gaps in Medicaid eligibility for parents and other non-disabled adults. In the absence of the expansion, adults without dependent children in 11 of the 17 southern states remain ineligible for Medicaid regardless of how low their incomes are. Moreover, eligibility limits for parents remain below 50% FPL ($9,895 per year for a family of three) in eight southern states (see Appendix Table 5). Overall, the median Medicaid eligibility limits for parents (52% FPL) and childless adults (0% FPL) in the South are far lower than the median limits for other regions (Figure 16). In addition, even though Medicaid and CHIP eligibility limits for children and pregnant women in the South remain higher than those for adults, they are still low compared to other regions.

Figure 16: Median Medicaid/CHIP Eligibility Limits by Population and Geographic Region, as a Percent of the Federal Poverty Level, January 2014

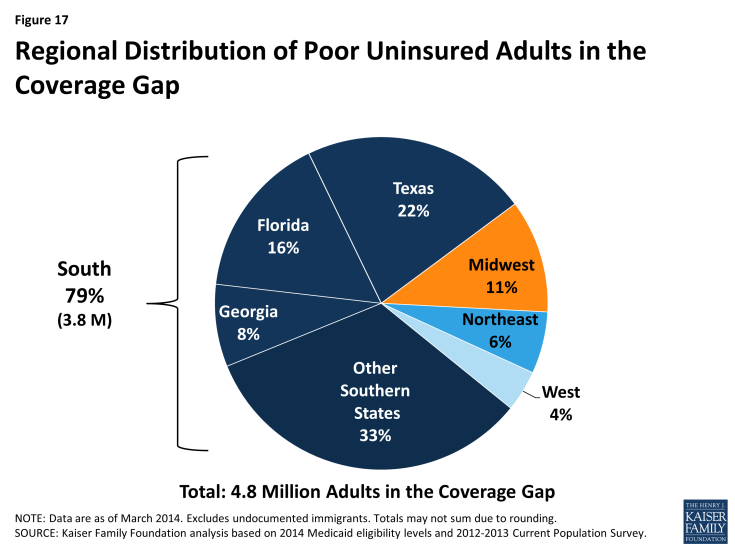

Nearly 4 million poor uninsured Southerners fall into a coverage gap because they remain ineligible for Medicaid but do not earn enough to qualify for the premium tax credits for Marketplace coverage. Because the ACA envisioned that low-income people would receive coverage through Medicaid, the tax credit subsidies to help people purchase private coverage through the Marketplace are only available to people with incomes at or above the poverty level ($11,670 for and individual and $19,790 for a family of three in 2014). Consequently, in states that do not expand Medicaid, uninsured adults with incomes above Medicaid eligibility limits but below poverty fall into a “coverage gap.” These individuals earn too much to qualify for Medicaid but not enough to qualify for the premium tax credits. Over half (51%) of uninsured adults in the South who would be eligible for Medicaid if their states implemented the expansion fall into this coverage gap (Table 3). These 3.8 million poor uninsured adults in the South, nearly half of whom (46%) reside in Texas, Florida, and Georgia, make up nearly eight in ten of the 4.8 million poor uninsured adults who fall into the coverage gap nationwide (Figure 17).

| Table 3: Number of Uninsured Nonelderly Adults in the ACA Coverage Gap, by State | |||

| State | Number in Coverage Gap | As a Share of All Uninsured Nonelderly Adults in State | As a Share of Uninsured Nonelderly Adults Who Would Be Eligible for the Medicaid Expansion (<138% FPL) |

| National Total | 4,831,580 | 27% | 30% |

| Total in South | 3,800,940 | 25% | 51% |

| Alabama | 191,320 | 36% | 64% |

| Florida | 763,890 | 27% | 58% |

| Georgia | 409,350 | 31% | 61% |

| Louisiana | 242,150 | 34% | 60% |

| Mississippi | 137,800 | 37% | 62% |

| North Carolina | 318,710 | 28% | 61% |

| Oklahoma | 144,480 | 28% | 58% |

| South Carolina | 194,330 | 33% | 66% |

| Tennessee | 161,650 | 24% | 60% |

| Texas | 1,046,430 | 27% | 56% |

| Virginia | 190,840 | 25% | 48% |

| SOURCE: KFF analysis of March 2012 and 2013 CPS and Medicaid MAGI eligibility levels. For more information, see Kaiser Family Foundation. “The Coverage Gap: Uninsured Poor Adults in States that Do Not Expand Medicaid.” October 2013 https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/the-coverage-gap-uninsured-poor-adults-in-states-that-do-not-expand-medicaid/ | |||

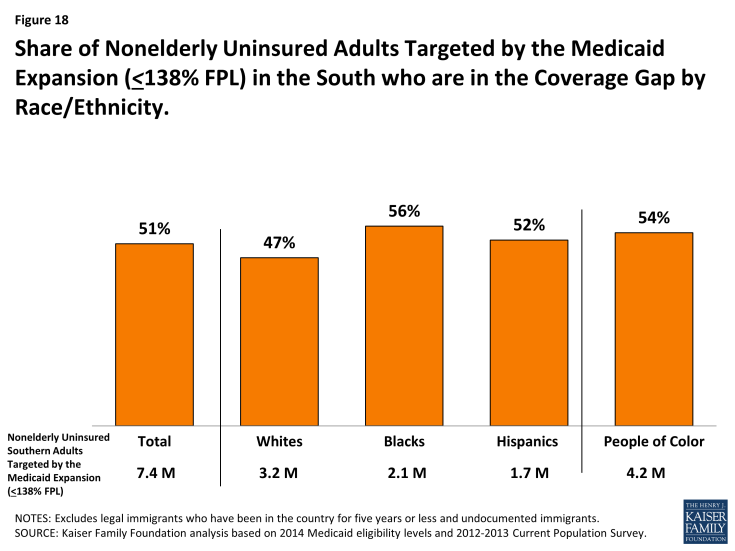

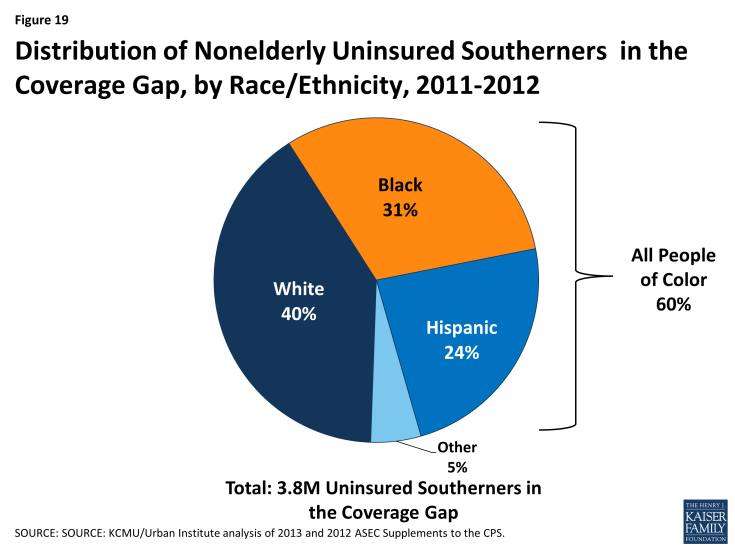

People of color are disproportionately affected by the coverage gap. Within the South, the impact of the coverage gap varies across racial and ethnic groups, reflecting the fact that Blacks are more likely than Hispanics to live in the South and to be uninsured. Overall, among uninsured adults in the South who would be eligible for Medicaid under the ACA expansion, 54% of adults of color and 56% of Blacks fall into the coverage gap, compared to less than half (47%) of Whites (Figure 18).

Figure 18: Share of Nonelderly Uninsured Adults Targeted by the Medicaid Expansion (<138% FPL) in the South who are in the Coverage Gap by Race/Ethnicity

However, White adults are the largest racial or ethnic group in the coverage gap in the South. Four in ten poor adults in the South who fall into the coverage gap are White, compared to 31% who are Black, and about one quarter (24%), who are Hispanic (Figure 19). In total, 1.5 million poor, White adults and 2.3 million people of color in the South fall into the coverage gap.

Figure 19: Distribution of Nonelderly Uninsured Southerners in the Coverage Gap, by Race/Ethnicity, 2011-2012

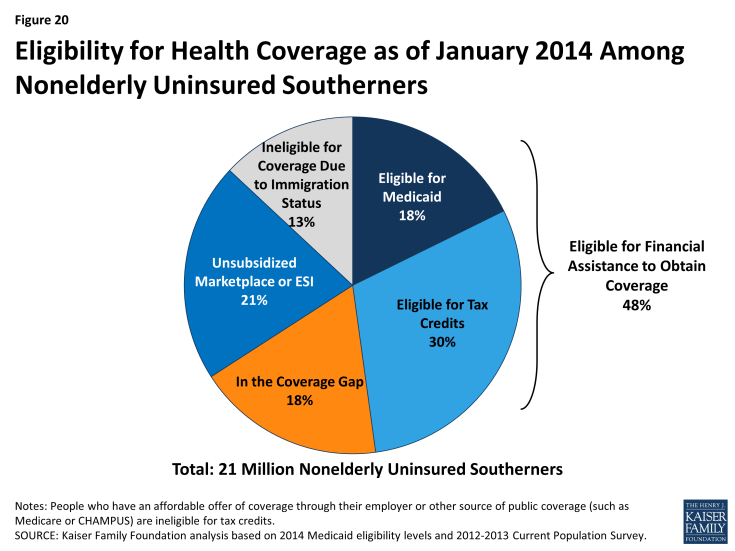

Even with these gaps in coverage, nearly half (48%) of the 21 million uninsured Southerners are eligible for financial assistance for health coverage in 2014 (Figure 20). About 30% of uninsured Southerners are eligible for premium tax credits to purchase Marketplace coverage and 18% are eligible for Medicaid or CHIP, including those newly eligible in the states implementing the Medicaid expansion as well as individuals who were already eligible but not yet enrolled, who are mostly children. Nearly one in five uninsured Southerners (18%) fall into the coverage gap because they reside in a state that is not implementing the Medicaid expansion. The remaining third (34%) of uninsured Southerners are not eligible for assistance for health coverage. About one in five (21%) do not qualify for the premium tax credits because they have incomes above 400% FPL or have access to affordable coverage through their employer. These individuals can still purchase unsubsidized coverage through the Marketplaces. The other 13% are not eligible to enroll in Medicaid and are barred from purchasing coverage through the Marketplaces due to their immigration status; they will likely remain uninsured.5

Figure 20: Eligibility for Health Coverage as of January 2014 Among Nonelderly Uninsured Southerners

Connecting Individuals to Coverage Through Outreach and Enrollment

Effective outreach and enrollment efforts are key to ensuring that the millions of uninsured Southerners who are eligible for coverage are enrolled. Even with remaining coverage gaps, millions of uninsured individuals in the South have gained access to new coverage options under the ACA. Effective outreach and enrollment efforts will be important for successfully enrolling these individuals, including targeted efforts to reach people of color, immigrant families, rural populations, low- and moderate-income families, and people with serious health needs. Regardless of state decisions to expand Medicaid, the ACA requires all states to adopt new approaches to simplify enrollment and renewal that make it easier for individuals to apply for and retain coverage. These include providing multiple application avenues for families (including online, by phone, and in person) and moving to technology-driven eligibility verification processes.6 Through previous experience with Medicaid and CHIP, a number of southern states have demonstrated that these and other strategies can be effective ways to enroll eligible populations into coverage while improving efficiency and minimizing burdens on state agencies (see Box 1). Looking forward, these state experiences provide key lessons for improving access to coverage in the South.

| Box 1: Examples of Innovative Outreach and Enrollment Policies in the South |

|

Oklahoma: Streamlining the Application and Renewal Process with the Use of Technology. In September 2010, Oklahoma became the first state to launch a real-time Medicaid and CHIP eligibility system to allow individuals to apply for coverage over the internet. The state verified applicants’ self-attested income electronically after making an initial eligibility determination, reducing the need for paper documentation. With the electronic verification system, enrollees were also able to review, update, and renew their coverage at any time. The new processes developed by the state reduced manual processes required by eligibility workers, and one year after implementing the enrollment system, the state estimated that it was able to process more than a thousand applications per day, and 90 percent received on-the-spot eligibility determinations, even when state offices were closed.7

.

South Carolina: Simplifying Renewals through Express Lane Eligibility. In 2011, South Carolina initiated a data-driven decision-making process to identify potential simplifications to its Medicaid enrollment process. Using data analysis, the state identified significant churn in its Medicaid program that was creating burdens for families, administrative staff, and providers. The state moved quickly to begin using eligibility findings from its Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program to conduct express lane renewals, resulting in coverage renewals for about 80,000 children in just nine months. The state estimated direct administrative cost savings of $1 million and 50,000 hours in staff time per year from implementing express lane eligibility at renewal.8,9

.

Louisiana: Improving Retention through Over Time through Incremental Policy Changes. In the years leading up to ACA implementation, Louisiana implemented several policy changes to improve retention for families enrolled in Medicaid and CHIP. In 2000, the state implemented an ex parte renewal process in which the state reviewed eligibility information available through the SNAP and TANF programs before closing a case. In 2003, the state implemented telephone renewals, and in 2005, began an administrative renewal process in which the state auto-renewed cases that had a very low likelihood of ineligibility at renewal. Following implementation of this policy, the proportion of children in CHIP who lost coverage at renewal due to procedural or administrative reasons fell from 17 percent to less than 1 percent. As of May 2013, only 4 percent of Medicaid renewals occurred through the use of a paper form, and most (69%) renewed though express lane eligibility or administrative renewals. Coupled with organizational changes, Louisiana found that these efforts helped to reduce burdens on eligibility staff while maintaining low error rates.10

.

Arkansas and West Virginia: Using Targeted Enrollment Strategies to “Fast Track” Medicaid-Eligible Individuals Into Coverage. In late 2013, Arkansas and West Virginia took advantage of a new option to facilitate the enrollment of eligible individuals into Medicaid using data already available to the state. Both states received approval to use data from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) to identify Medicaid-eligible adults, and West Virginia also implemented the option to use Medicaid and CHIP enrollment data for children to reach eligible parents. In less than two months, over 63,400 people had been verified eligible and enrolled into Medicaid in Arkansas, and 54,100 people had been verified as eligible and enrolled into Medicaid in West Virginia. Both states found the fast track approach to be an effective way to jump-start enrollment into their Medicaid expansions while minimizing burdens on individuals, staff, and enrollment systems.11

|