Getting into Gear for 2014: Shifting New Medicaid Eligibility and Enrollment Policies into Drive

Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility as of January 1, 2014

Conversion to Modified Adjusted Gross Income to Determine Financial Eligibility

The ACA changes how financial eligibility will be determined for many Medicaid beneficiaries, standardizing the approach across states as well as health insurance affordability programs. Beginning January 2014, financial eligibility for parents, pregnant women, children, and the expansion adults will be based on Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI), as defined in the Internal Revenue Code. The move to MAGI for these non-elderly, non-disabled groups will result in some changes from current Medicaid rules related to calculating family size and income and will largely align Medicaid financial eligibility determinations with the standards used to determine eligibility for premium tax credits and cost-sharing reductions in the new Marketplaces.1 Aligning the determination requirements across all insurance affordability programs is intended to promote seamless coordination and avoid gaps or overlaps in eligibility.2

To carry out the transition to MAGI, states must convert their existing Medicaid and CHIP eligibility levels for these groups to MAGI-equivalent levels. Today there is significant variation across states and eligibility categories in how income disregards and deductions are applied to determine if an individual meets the financial eligibility requirements for Medicaid or CHIP. For example, a state often disregards certain income from an individual’s gross income (e.g., $90 for a working parent), deducts certain expenses (e.g., childcare), and then compares the result to a net income standard.3 When states transition to MAGI, they will discontinue the use of these disregards and deductions; instead, they will use the MAGI-equivalent income threshold that takes into account states’ previous use of disregards and deductions and apply a standard disregard of five percentage points of the federal poverty level in certain circumstances (Box 2). States worked with CMS to develop their converted MAGI levels using one of three available methods.4

Box 2: Use of the Five Percentage Point of the Federal Poverty Level Disregard Under MAGI

Under the new MAGI rules, a standard income disregard of five percentage points of the federal poverty level will be applied, but only if it affects an individual’s eligibility. For example, the Medicaid expansion for adults extends eligibility to 133 percent of the FPL. However, a parent with income at 138 percent of the FPL in a state implementing the expansion would be determined eligible because after the five percentage point disregard, he or she would meet the income standard of 133 percent FPL. Upper income levels reported in this brief take into account this standard disregard.

The MAGI converted thresholds are intended to approximate states’ existing eligibility levels in the aggregate to prevent individuals from losing coverage due to the transition to MAGI. While MAGI converted thresholds differ from existing levels, they are designed to result in roughly the same number of people being eligible under the new standard as would have been eligible under the old standard (Box 3). In some cases, the converted thresholds will be the income eligibility limits in place as of January 1, 2014. For example, in most of the states not implementing the Medicaid expansion, the income limit for parents will be the MAGI conversion of their existing parent eligibility level. The MAGI converted thresholds will also be used for a number of other purposes, including 1) maintaining Medicaid and CHIP eligibility levels for children through October 1, 2019, as required by the ACA; 2) establishing minimum eligibility thresholds for parents, pregnant women, and other adults;5 3) determining the income levels at which premiums will apply; and 4) calculating the availability of the enhanced matching rate for newly-eligible adults.

Box 3: Understanding Differences Between January 2013 and January 2014 Eligibility Levels

Appendix Tables 1-3 show income eligibility levels for children, pregnant women, parents and other adults as of January 2013 and January 2014.

- In some cases, differences between the 2013 and 2014 levels represent state changes in eligibility policy, such as the Medicaid expansion to parents and other adults.

- In other cases, the differences stem from distinctions in how disregards were reflected in the January 2013 and January 2014 levels and do not represent a change in eligibility. For example, January 2013 eligibility levels for working parents reflect the maximum amount of income or earnings disregards, but not other deductions, that were applied in that state under previous rules. In contrast, the January 2014 MAGI-converted thresholds were calculated based on the average use of all disregards and deductions. For children and pregnant women, the January 2014 MAGI converted levels are higher than previously reported income thresholds because the January 2013 thresholds did not reflect states’ use of disregards or deductions.

States that had previously aligned children’s coverage levels across the different age groups merged the groups for conversion purposes in order to preserve the alignment. Otherwise, states were required to convert each eligibility category separately, including their Medicaid thresholds for infants, children ages one to five, and children ages six to eighteen. If the amount of the average disregards and/or the original threshold differed between the groups, disparate converted levels across the ages could result, as is seen in 18 states (Appendix Table 1). States have an opportunity to standardize their eligibility thresholds by adjusting the level for the older group to match that of the younger group, but only until December 31, 2013.6

Income Eligibility Limits as of January 1, 2014

Beginning in 2014, as part of the continuum of coverage, the ACA expands Medicaid to nearly all adults with incomes at or below 138 percent of the FPL. Moreover, the ACA requires states to maintain eligibility thresholds for children that are at least equal to those they had in place at the time the law was enacted through September 30, 2019. To help preserve the base of coverage upon which the ACA expansions build, states were also required to maintain eligibility levels for other groups, but this requisite will end on January 1, 2014.

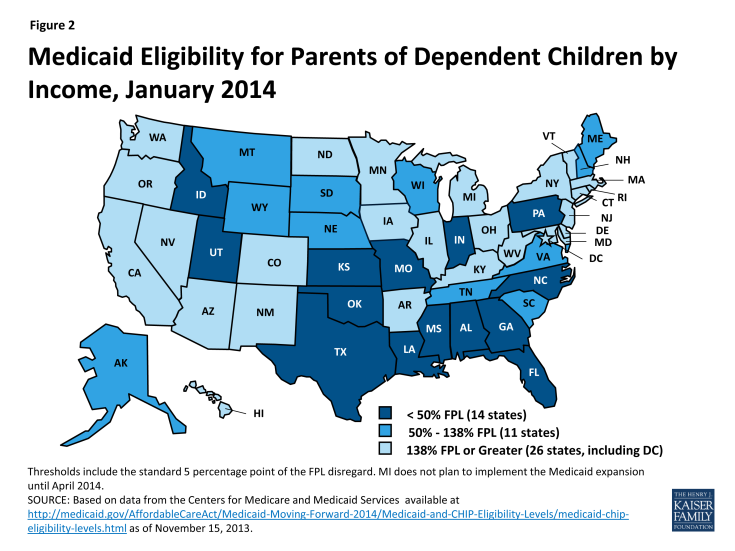

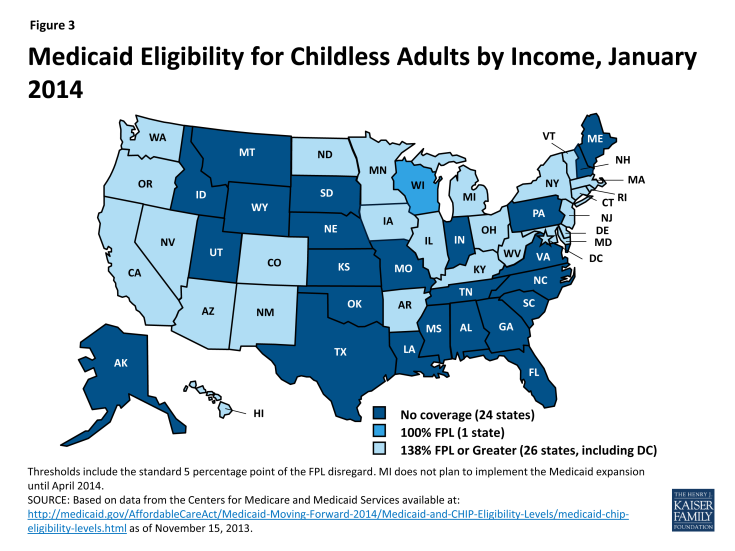

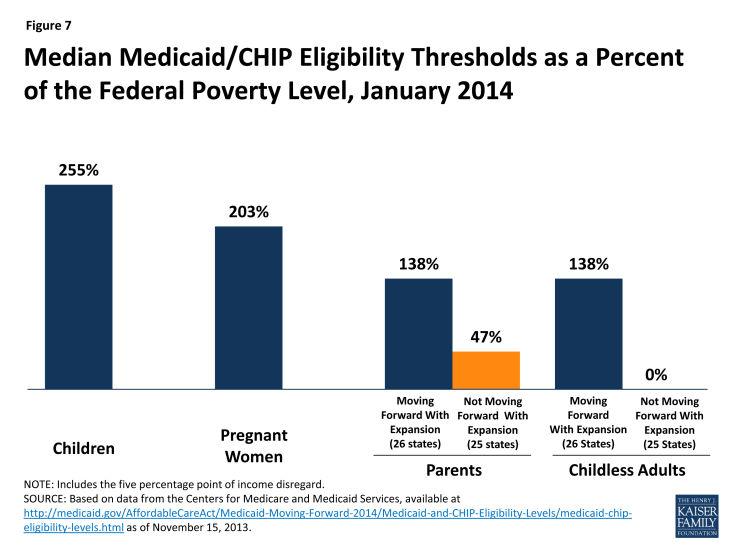

Eligibility levels for parents and childless adults will significantly increase in the 26 states, including DC, that are expanding Medicaid to adults. Fifteen (15) of the 26 states moving forward with the Medicaid expansion already cover parents at or above the poverty level through Medicaid, but adults without dependent children are eligible for full Medicaid coverage in just nine (9) of these states (AZ, CO, CT, DE, DC, HI, MN, NY, and VT), of which only six (6) cover them at or above poverty (Appendix Table 2). In the expansion states, eligibility levels will increase for parents in 16 states and for childless adults in 24 states. Overall, the median eligibility threshold for parents in these states will increase from 106 to 138 percent of the FPL, while the median threshold for adults without dependent children will increase from 0 to 138 percent of the FPL. Three (3) states (CT, DC, and MN) will cover parents above the new expansion level of 138 percent of the FPL (Figure 2) and the District of Columbia and Minnesota will cover adults without dependent children above this level (Figure 3), although Minnesota will reduce eligibility levels for parents relative to its 2013 levels. In addition, four (4) other states (NJ, NY, RI, and VT) that previously extended Medicaid eligibility to parents with incomes above 138 percent of the FPL are reducing eligibility to 138 percent of the FPL as of January 2014; many of these parents will be eligible for tax credits to purchase coverage through the new Marketplaces.

In the 25 states not expanding Medicaid at this time, many poor parents and other adults will remain ineligible for coverage. In 21 of the states, eligibility levels for parents will be below 100 percent of the FPL, with eligibility levels remaining below half of poverty in 14 states. In addition, Maine and Wisconsin will reduce eligibility for parents from 133 to 105 percent of the FPL and 200 to 100 percent of the FPL, respectively, as the requirement to maintain coverage ends on January 1, 2014. Adults without dependent children generally will remain ineligible for full Medicaid coverage in non-expansion states. Overall, in these 25 states, the median eligibility level for parents will be just 47 percent of the FPL, with only four (4) states (AK, ME, TN, and WI) covering parents with incomes at or above poverty; only Wisconsin will provide full Medicaid coverage to adults without dependent children. Parents and other adults with incomes above these limited Medicaid eligibility levels but below 100 percent of the FPL will fall into a coverage gap, which will leave nearly five million uninsured adults without access to a new coverage option (Box 4).

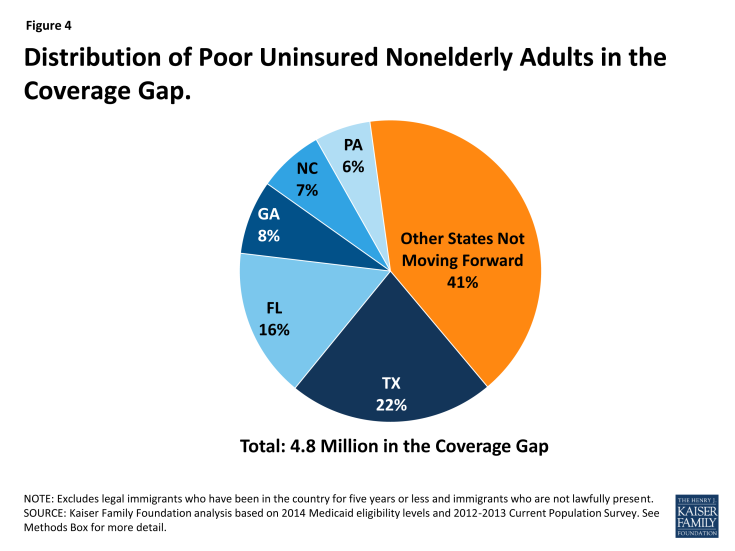

Box 4: The Coverage Gap Could Leave Nearly 5 Million Poor Adults Uninsured

Nationally, nearly five million poor uninsured adults will fall into the “coverage gap” because they live in states that are not expanding Medicaid to adults at this time. Those in the gap earn too much to qualify under their state’s Medicaid eligibility guidelines and too little to qualify for premium tax credits to purchase coverage through the new Marketplaces. More than one-third of those falling in the gap reside in just two states – Texas (22 percent) and Florida (16 percent) (Figure 4).

See: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, “The Coverage Gap: Uninsured Poor Adults in States that Do Not Expand Medicaid.” October 2013.

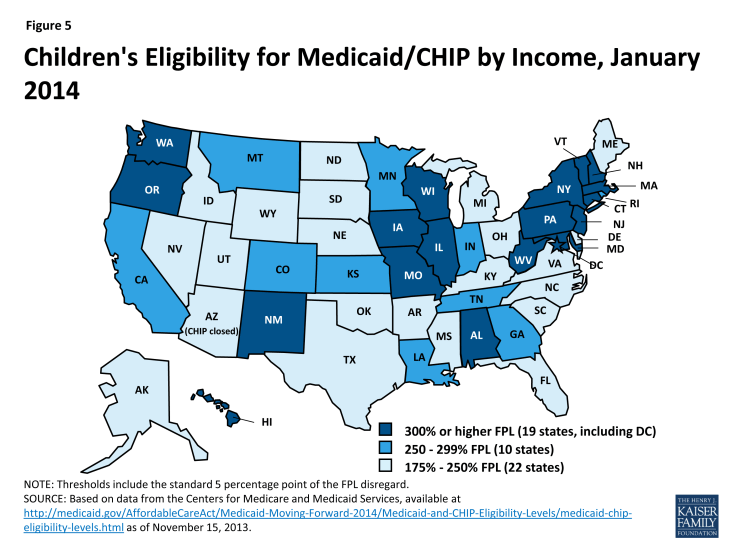

Coverage for children through Medicaid and CHIP will remain strong in 2014, with the median eligibility level at 255 percent of the FPL. More than half of the states (30, including DC) will cover children in families with incomes at or above 250 percent of the FPL and 20, including DC, will cover children in families with incomes at or above 300 percent of the FPL (Figure 5 and Appendix Table 1). Moreover, 18 states currently covering older children up to 133 percent of the FPL in separate CHIP programs will shift coverage for these children to Medicaid, as the ACA establishes a minimum Medicaid eligibility level of 138 percent of the FPL for all children up to age 19.7 Prior to the ACA, states were required to cover children up to age 6 with incomes up to 133 percent of the FPL through Medicaid, but the minimum eligibility level for older children was 100 percent of the FPL. This shift from CHIP to Medicaid must occur regardless of whether the state is expanding Medicaid to adults; states will continue to receive the enhanced CHIP matching rate for uninsured children in this income group. CMS has been assisting states with this shift and, in some cases, may permit an alternative transition approach, such as at a child’s next regularly scheduled renewal rather than by January 1, 2014.

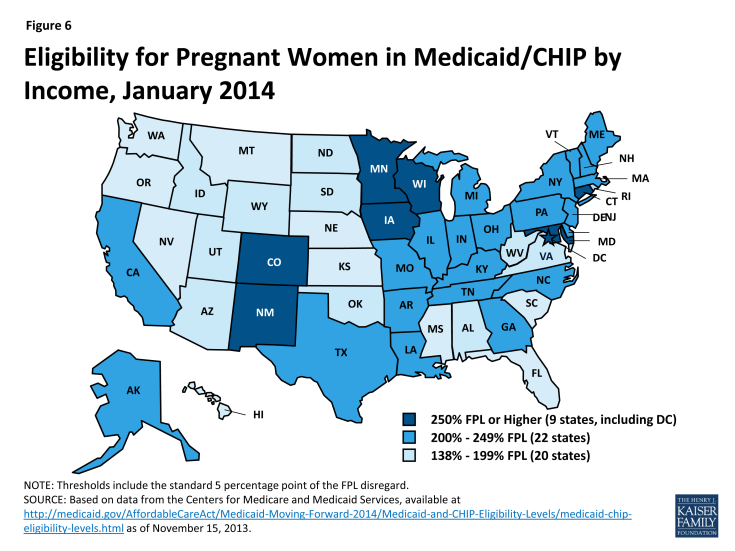

Despite two (2) states reducing eligibility, most will continue to cover pregnant women above the federal minimum standards. As of January 1, 2014, the median eligibility level for pregnant women will be 203 percent of the FPL, with 31 states, including DC, covering pregnant women at or above 200 percent of the FPL (Figure 6 and Appendix Table 3). Two states, Oklahoma and Virginia, will reduce eligibility for pregnant women from 185 to 133 percent of the FPL and 200 to 143 percent of the FPL, respectively, as the requirement to maintain coverage ends on January 1, 2014. Louisiana has also indicated plans to reduce eligibility for pregnant women as of January 1, 2014, but this change was not reflected in the data from CMS as of November 15, 2013.8

Eligibility for parents and other adults will continue to lag behind that of children and pregnant women. While coverage for parents and childless adults will markedly improve in states implementing the Medicaid expansion, their median eligibility levels will still remain significantly lower than that of children and pregnant women. These disparities in eligibility across groups will be even starker in states that are not expanding Medicaid (Figure 7).