Estimated Impacts of Final Public Charge Inadmissibility Rule on Immigrants and Medicaid Coverage

Introduction

In August 2019, the Trump Administration published a DHS final rule to change “public charge” inadmissibility policies. Under longstanding immigration policy, federal officials can deny entry to the U.S. or adjustment to LPR status (i.e., a “green card”) to someone they determine to be a public charge. Based on Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the SIPP 2014 Panel and 2017 ACS data, this analysis provides updated estimates of the:

- Share of noncitizens who originally entered the U.S. without LPR status who have characteristics that DHS could potentially weigh negatively in a public charge determination; and

- Number of individuals who might disenroll from Medicaid under different scenarios in response to the rule.

Background

Under longstanding policy, if authorities determine that an individual is likely to become a public charge, they may deny that person’s application for LPR status or entry into the U.S.1 Public charge determinations are a forward-looking test in which officials will assess the likelihood of someone becoming a public charge in the future. Specifically, DHS finds an individual “inadmissible” if officials determine that he or she is more likely than not at any time in the future to become a public charge.

The rule redefines public charge and broadens the programs that the federal government will consider in public charge determinations to include previously excluded health, nutrition, and housing programs (Table 1). Under previous policy, a person was considered a public charge if officials determined he or she was likely to become primarily dependent on the federal government as demonstrated by use of cash assistance programs or government-funded institutionalized long-term care. Guidance specifically clarified the exclusion of Medicaid and other non-cash programs from these decisions because of concerns that fears were limiting enrollment of families. Under the new rule, officials will determine someone to be a public charge if they determine an individual is more likely than not at any time in the future to receive one or more public benefits for more than 12 months in the aggregate within any 36-month period (such that, for instance, receipt of two benefits in one month counts as two months). Further, the rule defines public benefits to include federal, state, or local cash benefit programs for income maintenance and certain health, nutrition, and housing programs that were previously excluded from public charge determinations, such as non-emergency Medicaid for non-pregnant adults, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and several housing programs.

| Table 1: Change in Public Charge Definition and Programs Considered | ||

| Previous Policy | Policy Under New Rule | |

| Public Charge Definition | Likely to become primarily dependent on the federal government as demonstrated by use of cash assistance programs or government-funded institutionalized long-term care. | More likely than not at any time in the future to receive one or more public benefits for more than 12 months in the aggregate within any 36-month period (such that, for instance, receipt of two benefits in one month counts as two months). |

| Programs Considered in Public Charge Determinations |

|

|

Officials make public charge determinations based on the totality of the person’s circumstances. At a minimum, officials must take into account an individual’s age; health; family status; assets, resources, and financial status; and education and skills. The rule describes how DHS will consider each factor and identifies characteristics it will deem as positive factors that reduce the likelihood of an individual becoming a public charge and negative factors that increase the likelihood of becoming a public charge. DHS indicates that no single factor would govern a determination, and it appears officials would retain significant discretion in assessing factors and making determinations. The rule establishes a new income standard of 125% of the federal poverty level (FPL) ($26,663 for a family of three as of 2019) and specifies that family income below that standard is a negative factor. Some other negative factors include having a lower education level, a health condition, lacking private health insurance, not being employed or a primary caregiver, and having limited English proficiency. Examples of positive factors include being of working age, being in good health, having private health coverage, and having income at or above 125% FPL. The rule also specifies certain heavily weighted negative and positive factors.

The rule identifies previous or current use of public benefits as a negative factor, but most immigrants who would be seeking admission or adjustment to LPR status are already ineligible for these programs or are exempt from a public charge determination. For example, eligibility for the programs included in the rule for immigrants without LPR status is now largely limited to humanitarian immigrants such as refugees and asylees, who are exempt from the public charge test. However, since the public charge determination is a forward-looking test, even if an individual is not currently or has not previously used a public benefit, officials will assess the likelihood of an individual using those benefits in the future.

The new rule will likely lead to decreased enrollment in Medicaid and other programs among individuals in immigrant families beyond those directly affected by the rule, including their primarily U.S.-born children. Although few people directly affected by the rule are enrolled in Medicaid and the other public benefit programs, previous experience and recent research suggest that the rule will have chilling effects that would lead individuals to forgo enrollment in or disenroll themselves and their children from programs due to confusion and fear that their or their children’s enrollment could negatively affect their or another family member’s immigration status.3 For example, prior to the final rule, there were anecdotal reports of individuals disenrolling or choosing not to enroll themselves or their children in Medicaid and CHIP due to fears and uncertainty.4 Providers also reported increasing concerns among parents about enrolling their children in Medicaid and food assistance programs,5 and WIC agencies across a number of states have seen enrollment drops that they attribute largely to fears about public charge.6 A survey conducted prior to the final rule found that one in seven adults in immigrant families reported avoiding public benefit programs for fear of risking future green card status, and more than one in five adults in low-income immigrant families reported this fear.7

Characteristics of Noncitizens without LPR status

Using SIPP 2014 Panel data, we show characteristics that DHS could consider in a public charge determination under the rule among noncitizens who originally entered the U.S. without LPR status. Specifically, the analysis examines age, self-reported health status, family income, health insurance type, employment, education, and English proficiency (Appendix B). As noted, officials also will consider previous or current use of public benefits. However, because very few people without a green card are eligible for these programs who would be subject to a public charge test, this analysis does not include estimates of use of public programs.

These estimates illustrate the share of noncitizens living in the U.S. who might face barriers to adjusting to LPR status under the rule based on certain characteristics. Due to data limitations, they do not provide a precise count of the number of people within the U.S. who would be subject to public charge determinations. The estimates do not account for people who DHS could deny entry into the U.S. due to a public charge determination and do not account for all factors that DHS could consider in a public charge determination. As noted, officials would take into account the totality of an individual’s circumstances, and no single factor would govern a determination. How DHS would operationalize its assessment of factors may differ from SIPP’s measurement of characteristics. (See Appendix A: Methods for more detail.)

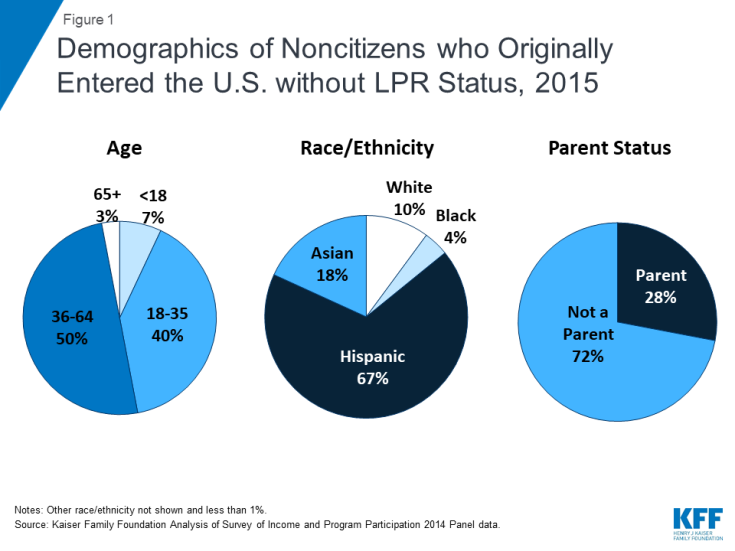

Noncitizens who entered the U.S. without LPR status include individuals across different ages, races/ethnicities, and family statuses. Although many were nonelderly Hispanic adults without a dependent child, 7% are a child, more than one in four is a parent (28%), and one-third (33%) is another race or ethnicity, including nearly one in five (18%) who is Asian (Figure 1).

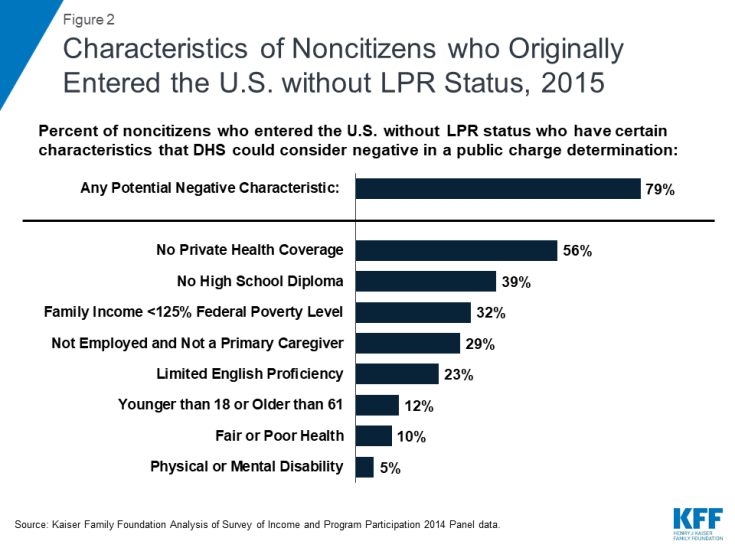

Nearly eight in ten (79%) noncitizens who entered the U.S. without LPR status have at least one characteristic that DHS could weigh negatively in a public charge determination under the rule. The most common characteristics examined that DHS could consider as negative factors include no private health coverage (56%), no high school diploma (39%), and having income below the new 125% FPL8 standard established by the rule (32%). (Figure 2 and Appendix B).

More than one in four (27%) noncitizens who originally entered the U.S. without LPR status have a characteristic that DHS could consider a heavily weighted negative factor examined in this analysis. Potential heavily weighted negative factors examined in this analysis include not being employed and not a full-time student or primary caregiver (29%), and having a disability that limits the ability to work and lacking private health coverage (3%). The rule identifies other heavily weighted negative factors that were not included in this analysis, including receipt of a public benefit for more than 12 of the previous 36 months and being found previously inadmissible or deportable on public charge grounds. As noted, very few people without a green card are eligible for these programs who would be subject to a public charge test. SIPP data do not provide information on previous determinations of inadmissibility or deportability based on public charge grounds.

Nearly all of noncitizens who originally entered without LPR status have at least one characteristic that DHS could consider as a positive factor. The most common positive factors are no physical or mental health disability (95%), excellent, very good, or good health (90%), and being of working age (between age 18 and 61) (88%). Over half (55%) have a heavily weighted positive factor, which includes having private health insurance (44%) or having family income at or above 250% FPL (36%). Given the high prevalence of at least one positive factor among the population, it’s unclear how officials would weigh the presence of a positive factor in a public charge test. As noted, officials will make public charge determinations based on a totality of an individual’s circumstances. However, the rule does not specify how officials will weigh different factors against each other, leaving officials significant discretion in making determinations on a case-by-case basis.

Nearly seven in ten (68%) of U.S. citizens (U.S. born and naturalized) also had one or more characteristics that DHS could potentially weigh negatively if they were subject to a public charge determination. Citizens were more likely than noncitizens who entered the U.S. without LPR status to have certain characteristics that DHS could consider negative, including being a child or older than age 61 and reporting fair or poor health and having a physical or mental disability that limits their ability to work (Appendix B).

Impact on Medicaid Enrollment

We also illustrate the number of Medicaid and CHIP enrollees who are noncitizens or citizens living in a household with at least one noncitizen who could disenroll under different potential disenrollment scenarios. We use 2017 American Community Survey (ACS) data for this analysis as ACS provides more recent estimates of health coverage than available through SIPP. Although CHIP was not included as a public benefit in the rule, many individuals are not able to distinguish between their enrollment in Medicaid versus CHIP, and ACS data do not provide separate Medicaid and CHIP coverage measures. As noted, previous experience and recent research suggests that the proposed rule may lead to broader disenrollment among individuals in families with immigrants beyond those the rule directly affects.

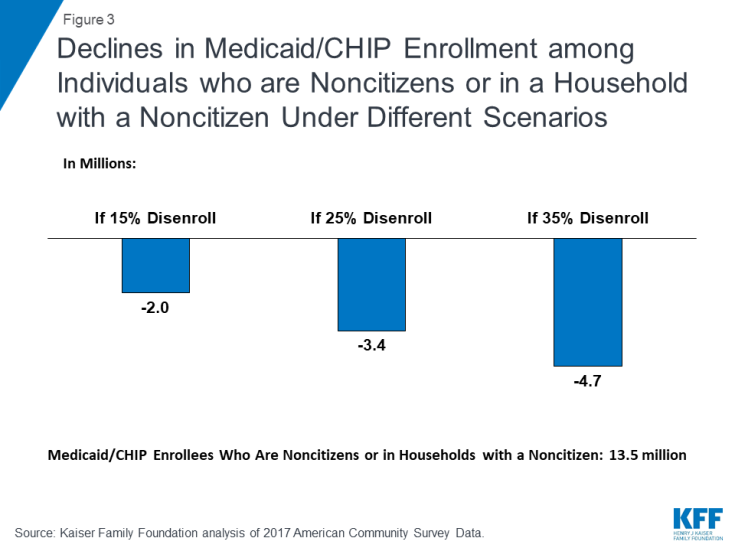

We applied disenrollment rates of 15%, 25%, and 35% to the total number of Medicaid and CHIP enrollees who are noncitizens or citizens living in a household with at least one noncitizen. It is difficult to predict what actual disenrollment rates may be in response to the rule. These disenrollment rates illustrate a range of potential impacts and draw on previous research on the chilling effect welfare reform had on enrollment in health coverage among immigrant families.9 As noted, a 2019 survey fielded prior to finalization of the rule found that one in seven (13.7%) of adults in immigrant families reported avoiding public benefit programs for fear of risking future green card status, and more than one in five (20.7%) adults in low-income immigrant families reported this fear.10

According to the ACS data, there were over 13.5 million Medicaid/CHIP enrollees who were noncitizens or citizens living in a household with at least one noncitizen, including 7.6 million children, who may be at risk for decreased enrollment as a result of the rule. If the proposed rule leads to disenrollment rates ranging from 15% to 35%, between 2.0 million and 4.7 million Medicaid and CHIP enrollees who are noncitizens or citizens living in a family with at least one noncitizen would disenroll (Figure 3). Because very few noncitizens are eligible for Medicaid would be subject to public charge, this disenrollment would primarily be due to chilling effects of fear and confusion. The estimates provide illustrative examples and, due to data limitations, may reflect both an undercount of noncitizens and an overestimate of noncitizens receiving Medicaid. (See Appendix A: Methods for more detail.)

Figure 3: Declines in Medicaid/CHIP Enrollment among Individuals who are Noncitizens or in a Household with a Noncitizen Under Different Scenarios

Beyond potential disenrollment, the proposed rule may also deter new enrollment among the nearly 1.8 million uninsured individuals who are eligible for Medicaid and CHIP but not enrolled and are noncitizens or live in a household with a noncitizen. Specifically, there are 652,200 noncitizen adults and 219,100 noncitizen children who are uninsured but eligible for Medicaid or CHIP. In addition, there are 366,800 uninsured citizen adults and 602,400 uninsured citizen children who are eligible for one of the programs and live in a household with a noncitizen.11 Given continually evolving immigration trends, potential effects of the new rule on lawful immigration in the future, and families’ increased fears of accessing programs, the number of people living in a household with a noncitizen who enroll in Medicaid and CHIP may continually decline over time.

Implications

The rule will make it more difficult for some individuals, particularly those with low incomes and health needs, to obtain LPR status or immigrate to the U.S. For example, a full-time worker in a family of three earning the federal minimum wage would not have sufficient annual income ($15,080) to meet the new income standard established in the rule, which would be $26,663 for a family of three. As such, the rule will affect future immigration opportunities for individuals and families. The rule may also increase barriers to family reunification and potentially lead to family separation, particularly among families with mixed immigration statuses. For example, if DHS denies an individual a green card and that individual loses permission to remain in the U.S due to a public charge determination, he or she may have to leave other family members, such as a spouse or child who is a citizen or who has LPR status, in the U.S.

Reduced participation in Medicaid and other programs would negatively affect the health and financial stability of immigrant families and the growth and healthy development of their children, who are predominantly U.S.-born. Coverage losses would reduce access to care for families, contributing to worse health outcomes. Reduced participation in nutrition and other programs would likely compound these effects. In addition, the losses in coverage would lead to lost revenues and increased uncompensated care for providers and have broader spillover effects within communities.

This brief was prepared by Samantha Artiga and Rachel Garfield, with the Kaiser Family Foundation, and Anthony Damico, an independent consultant to the Kaiser Family Foundation.