Distributing a COVID-19 Vaccine Across the U.S. - A Look at Key Issues

Introduction

A vaccine or vaccines for COVID-19, the disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, may become available for use in the U.S. over the next several months. At that point, officials will begin the process of actually delivering vaccines to states and localities and overseeing their administration to individuals. It will be a historically complex challenge to ensure that enough vaccines are distributed in a rapid, effective, and equitable way. The U.S. has some experience with mass vaccine distribution to build on and has faced some of the challenges before, but delivering COVID-19 vaccines will need to be at a much greater scale than past efforts, and will also bring new and unique challenges.

While there are still many unknowns, it is likely that hundreds of millions of COVID-19 vaccine doses will have to be administered to people across the country to achieve an adequate level of protection. For example, by one estimate, 462 to 660 million doses of a vaccine could be needed for a two-dose regimen, and potentially more over time depending on the strength and duration of immunity and dosing requirements. While initial planning documents have been released, numerous outstanding questions and challenges remain. These range from questions regarding the respective roles of the federal, state, and local governments, to financing and coverage of a vaccine, addressing racial and ethnic disparities and communication and public trust. This brief outlines what is currently known about the U.S. COVID-19 vaccine distribution plan and discusses key issues and challenges as well as outstanding questions.

Jump to Key Policy Issue |

COVID-19 Vaccine Candidates and Timeframe for Availability in the U.S.

The U.S. government, through a multi-agency, public-private partnership, known as Operation Warp Speed (OWS), which was publicly launched on May 15, has provided pharmaceutical companies with over $10 billion in funding to support research, development, manufacturing, and distribution of eight different candidate COVID-19 vaccines. Through these efforts, the federal government has already effectively purchased hundreds of millions of doses of these vaccines, from multiple manufacturers, even as clinical trials and federal regulatory review are ongoing (see Table 1).

| Table 1: Characteristics of Known Operation Warp Speed COVID-19 Vaccine Candidates (as of October 15, 2020) |

|||||

| Company/ Candidate | Current Clinical Trial Phase | Number of Doses Likely Needed for Full Course | Agreement Amount | Number of Doses Owned by Federal Government | Notes |

| AstraZenecaAZD1222 Adenovirus-vector vaccine |

Phase 3 | 2 doses, injected |

up to $1.2 billion | 300 milliona | Supports advanced clinical studies, vaccine manufacturing technology transfer, process development, scaled-up manufacturing, and other development activities, to make available at least 300 million doses of a coronavirus vaccine. |

| Janssen (Johnson & Johnson) AD26.COV2.S Adenovirus-vector vaccine |

Phase 3b | 1 dose, injected |

$1 billion | 100 million | Supports demonstration of large-scale manufacturing and delivery of 100 million doses of vaccine. By funding this effort, the federal government will own the 100 million doses. The government can also acquire additional doses up to a quantity sufficient to vaccinate 300 million people. |

| Merck/IAVI V591 Recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus (rVSV) vector vaccine |

Phase 1/2 | 1 or 2 doses,b injected | $38 million | None reported | Supports accelerated development of an rVSV-SARS-CoV2 (recombinant) COVID-19 vaccine. Based on experience with the rVSV-based Ebola vaccine, a COVID-19 vaccine using the same rVSV platform has potential to provide a rapid and robust immune response. |

| Moderna mRNA-1273 RNA vaccine |

Phase 3 | 2 doses, injected |

$1.5 billion | 100 million | Supports manufacturing and delivering of 100 million doses of vaccine candidate. By funding this effort, the federal government will own the 100 million doses. The government can also acquire up to an additional 400 million doses. |

| Novavax NVX-CoV-2373 recombinant protein vaccine |

Phase 3 | 2 doses, injected | $1.6 billion | 100 million | Supports demonstration of commercial-scale manufacturing. By funding this effort, the federal government will own the 100 million doses. |

| Pfizer BNT162b2 RNA vaccine |

Phase 3 | 2 doses, injected | $1.95 billion | 100 million | Supports large-scale production and nationwide delivery of 100 million doses of a vaccine. By funding this effort, the federal government will own the 100 million doses. The government can also acquire up to an additional 500 million doses. |

| Sanofi/GlaxoSmithKline Recombinant SARS-CoV-2 Protein Antigen + AS03 Adjuvant | Phase 1/2 | 1 or 2 doses,b injected |

$2 billion | 100 million | Supports advanced development including clinical trials and large-scale manufacturing of 100 million doses. By funding this effort, the federal government will own the 100 million doses. The government can also acquire up to an additional 500 million doses. |

| NOTES: a The agreement between the federal government and AstraZeneca states that “at least 300 million doses will be made available” to the government. b Merck/IAVI and Sanofi/GlaxoSmithKline vaccine trials are testing 1 and 2 dose regimens. |

|||||

It is possible that one or more of the OWS vaccine candidates will become available for public use over the next several months. Four candidates have already advanced to Phase 3 trials, undergoing study in large groups of volunteers to determine their safety and efficacy. Under the most optimistic scenarios, initial trial results for at least one vaccine candidate could be available as early as the end of October. However, it is more likely results will start to become available later in the year or next year, and companies have said they would not start to pursue authorization until late November at the earliest. Typically, vaccines are approved through the FDA’s Biologic License Application (BLA) process, but during a public health emergency the FDA can grant an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for a vaccine even before full approval if certain criteria are met. Access through an EUA is accelerated compared to a BLA because the requirements are less stringent and vaccine use under an EUA could be more limited to specific target groups. It is expected that even if an EUA is granted, companies will continue to pursue full regulatory approval through the BLA process, which could be completed for some vaccine candidates in 2021.

It is also expected that upon FDA authorization or approval there will already be a limited number, perhaps tens of millions of doses, of a given vaccine ready to be shipped. Manufacturing is expected to ramp up after FDA authorization or approval, which would allow for distribution of an increasing number of doses over time. Eventually there could be multiple, competing vaccines that have been approved or authorized, raising questions about how the government will identify the preferred vaccine(s) and how people will differentiate between the various vaccines’ effectiveness and safety. It is also important to note that these vaccine candidates have so far been tested in non-pregnant adults only, and at least initially will likely not be recommended for use in children. Additional trials looking at vaccine effectiveness in children are likely to come later.

| Table 2: Key Terms/Entities Involved in the COVID-19 Vaccine Authorization and Approval Process |

|

| Term or Entity | Definition/Role |

| Operation Warp Speed (OWS) | The federal government’s multi-agency, public-private partnership “to accelerate the development, manufacturing, and distribution of COVID-19 vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostics”, with the goal producing and delivering 300 million COVID-19 vaccine doses in the United States. OWS is led by the Department of Health and Human Services (including CDC, FDA, NIH, and BARDA) and the Department of Defense. |

| Food and Drug Administration’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC) | The VRBPAC advises the FDA Commissioner “in discharging responsibilities as they relate to helping to ensure safe and effective– vaccines and related biological products for human use and, as required, any other product for which the Food and Drug Administration has regulatory responsibility.” It provides independent advice and recommendations. The VRBPAC may review a vaccine EUA request as well as BLA request. |

| Food and Drug Administration’s Biologics License Application (BLA) | Before formal vaccine approval by the FDA, a product must pass through three phases of clinical trials, starting with Phase 1 trials, with a small number of people and continuing to Phase 3 trials, large-scale, safety and effectiveness studies. After successful completion of all three trial phases (with specified endpoints met), a Biologics License Application (BLA) may be submitted. A BLA “is a request for permission to introduce, or deliver for introduction, a biologic product into interstate commerce”, that the FDA reviews to decide on approval.

The FDA released specific guidance for industry on the COVID-19 vaccine approval process in June 2020. The guidance recommends that a COVID-19 vaccine demonstrate evidence of being at least 50% effective, among other criteria, before seeking approval. |

| Food and Drug Administration’s Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) | During a public health emergency, the FDA can use its EUA authority to “allow the use of unapproved medical products, or unapproved uses of approved medical products, to diagnose, treat, or prevent serious or life-threatening diseases when certain criteria are met.” An EUA may be granted based on interim analysis of clinical endpoint data from a Phase 3 trial, and before a manufacturer has submitted and/or FDA has completed a formal review of a BLA.

The Secretary of HHS first declared COVID-19 to be a public health emergency on January 31, 2020 and has renewed this designation several times since. The FDA’s most recent EUA guidance for COVID-19 was released on October 6, 2020. As part of this guidance, the FDA has specified that data from Phase 3 trials should include a median follow-up duration of at least two months after completion of the full vaccination regimen before an EUA may be requested. |

| National Academy of Medicine Framework for Equitable Allocation of Vaccine for the Novel Coronavirus | The NIH and CDC sponsored a National Academies consensus study to assist policymakers in developing guidelines for the equitable allocation of COVID-19 vaccines, both domestically and globally. It is intended to inform a range of advisory groups and decision-making bodies, including the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). On October 2, the committee released its framework report. The framework identifies four risk-based criteria for prioritization– risk of acquiring infection; risk of severe morbidity and mortality; risk of negative societal impact; and risk of transmitting infection to others – and four allocation phases. |

| CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) | The ACIP was established under Section 222 of the Public Health Service Act (42 U.S.C. §2l7a), as amended. The ACIP provides advice and guidance to the Director of the CDC regarding use of vaccines for effective control of vaccine-preventable diseases in the United States. Recommendations made by the ACIP are reviewed by the CDC Director, and if adopted, are published as official CDC/HHS recommendations. This typically includes advice regarding vaccines already licensed for use in the U.S., but guidance can be issued for unlicensed vaccines, such as those authorized under an EUA. |

Plans for U.S. Distribution of COVID-19 Vaccines

The federal government has released several documents addressing how vaccine distribution will proceed. On August 4, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provided state and local health departments with interim vaccine planning assumptions and action steps to inform development of COVID-19 pandemic vaccination plans. Actual planning documents were provided to health authorities on August 27; at this time, CDC also sent a letter to governors asking them to ensure distribution sites in their states could be operational by November 1. OWS provided Congress with a federal vaccine distribution strategy, and CDC released an interim playbook for jurisdiction operations on September 16. In the playbook, CDC says jurisdictions are required to develop and submit vaccination plans by October 16, 2020. Finally, on September 23, HHS announced that it was providing $200 million to state and local jurisdictions specifically for vaccine preparedness. An OWS organization chart provides additional information on the leadership structure and respective roles of federal agencies.

Based on these documents, current U.S. distribution plans are as follows:

- After FDA authorization or approval, the federal government and 64 state, local, and territorial jurisdictional immunization programs1, that CDC funds and works with, will begin to oversee delivery of available vaccine doses to approved administration sites across the country. At first, there will be few vaccine doses available, so the federal government will determine the number of doses allocated to each jurisdiction. This allocation will depend on which vaccine(s) are approved, the number of doses available for those vaccines, the population of jurisdictions, and potentially other factors.

- Distribution is expected to unfold in phases. Jurisdictions have been told to use the following assumptions in planning for each phase. In Phase 1, an initial limited supply of vaccine doses would be available, and therefore likely be prioritized for certain groups and distribution and administration more tightly controlled. In Phase 2, the vaccine supply would be increased and access expanded to include a broader set of the population, with additional providers involved in administration. In Phase 3, there would likely be sufficient supply to meet demand, and distribution would be integrated into routine vaccination programs. (Many of the distribution issues discussed in this brief refer to challenges faced especially during Phase 1 and Phase 2).

- Pre-approved administration sites will make requests for vaccine doses to their jurisdiction’s immunization program, which will review and approve these requests according to its allocation of vaccines from the federal government. Jurisdictions’ immunization programs will submit orders to the federal government (initially to OWS, potentially later to CDC as well). Once reviewed by federal officials, vaccine doses will be delivered by a central distributor to administration sites within 48 hours of approval. This stands in contrast to the distribution system used for seasonal influenza where, outside of the CDC’s Vaccines for Children Program (VCP) and the Section 517 Immunization Program (described below), vaccine production and distribution are primarily handled by the private sector. For COVID-19, the federal government has selected McKesson Corporation as its central distributor. McKesson currently serves as the central distributor for the VCP and was the central distributor during H1N1 pandemic influenza in 2009-2010.

- In addition to vaccines being delivered by the central distributor via orders received from jurisdictions’ immunization programs, the federal government may also ship doses to designated secondary vaccine depots and receive orders from and ship doses directly to some private partners with agreements in place such as large retailers and pharmacies, especially as more doses become available.

- Federal, state, and local government officials will determine a prioritization schedule for how to allocate the initially limited vaccine doses to specific population groups. Federal agencies asked the National Academies of Medicine (NAM) to develop a framework for prioritization, which NAM released on October 2. The NAM findings will inform additional recommendations and policies to be developed by the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), the official federal advisory committee that informs CDC’s immunization policies, practices, and recommendations. The NAM framework and initial discussions at ACIP indicate that high-risk workers in health care facilities, first responders, and persons at elevated risk from COVID-19 disease such as the elderly, are likely to be among the groups prioritized for receipt of the early, limited number of vaccine doses.

- Indications are that the administration of the vaccine to individuals will likely take place in a wide variety of locations, including: public and private hospitals and clinics (e.g., federally qualified health centers, rural health centers), medical practices, pharmacies, and potentially government-run mass vaccination locations. Jurisdictions’ immunization programs and the federal government will work together to identify and approve distribution sites and expect the need to expand the network of partner sites to reach all target populations.

- While the U.S. military has been a key part of the OWS effort by supplying logistical, program management, and contracting expertise, current plans do not include a major role for the military in distributing Covid-19 vaccines to the general public.

Policy and Implementation Issues and Questions

Even with the release of these documents, many outstanding questions and a myriad of potential issues remain. Some of these are dependent on the specific characteristics of any vaccine that is authorized or approved (e.g., the number of doses needed, storage requirements, and the target recipient profile), and final decisions regarding an allocation framework. Others are due to the unprecedented scale and complexity of the COVID-19 pandemic, including its devastating health and economic impacts and disproportionate impact in some communities, particularly communities of color. Still others are due to existing policy barriers and challenges, resource constraints, and unresolved decisions on the part of federal, state, and local governments. Finally, the hyper-partisan nature of the COVID-19 response in the U.S. has contributed to growing public mistrust and skepticism of a COVID-19 vaccine, presenting particular challenges for vaccine adoption. We examine some of these key issues below. This list is not meant to be exhaustive; for example, we do not examine in detail the issues around the prioritization of the potentially limited supply of vaccines, which is the subject of the NAM committee and will also be addressed by ACIP.

Funding for Vaccine Distribution

A critical and potentially limiting factor in the distribution of a COVID-19 vaccine is resource constraints faced by state and local health departments, who will have the main responsibility for managing vaccine distribution. Public health has long been underfunded in the U.S., and the health and economic impacts of the pandemic have further strained state and local public health infrastructure and reduced state revenues upon which they depend. Many have yet to meet the testing and contact tracing needs they already face, let alone be ready to distribute a new vaccine. To date, Congress has appropriated approximately $2.45 billion across two of the four emergency COVID-19 relief bills2 to states, localities, and territories for a range of COVID-19 public health activities that, while not specific to vaccines, could include vaccine-related activities. Thus far, of these amounts, CDC has awarded $200 million from CARES Act funds to jurisdictions for vaccine preparedness, well below what is likely needed for such a large scale effort. At a September 16 hearing of the Senate Appropriations Subcommittee Hearing on Coronavirus Response, CDC Director Redfield stated that state and local jurisdictions needed $6 billion to support COVID-19 vaccine distribution, while the National Association of City and County Health Officers estimates the need at $8.4 billion. The Association of Immunization Managers, which represents the 64 state, local, and territorial immunization programs, has said that additional funds are needed for shoring up the health care workforce, opening new vaccine administration sites, adapting information systems, purchasing personal protective equipment, and combating disinformation and vaccine hesitancy, among other areas. Concerns about funding challenges have also been raised by the National Governors Association. Negotiations between Congress and the Administration on a fifth COVID-19 relief bill, which would have included billions for vaccine distribution (the House Democratic bill, the Heroes Act, included $7 billion and the Senate Republican bill included $6 billion), are stalled, so it is unclear when additional funding will be made available to states for this purpose.

Supply, logistics, and monitoring

Government-led vaccine distribution in the timeframe and at the scale being contemplated for COVID-19 has never before been done in the U.S., with hundreds of million doses needing to be distributed, over as short period of time as possible, in order to vaccinate most of the U.S. population. In contrast, in a typical year, CDC distributes about 75 million vaccine doses to health departments and private providers. In the context of the H1N1 pandemic during 2009-2010, the government distributed 124 million doses of the H1N1 pandemic influenza vaccine over the course of several months. In recent years, over 150 million doses of seasonal influenza vaccines have been delivered in the U.S. per year, though, as mentioned above, outside of the VCP and 317 programs, these vaccines are primarily distributed via the private sector, not by the government. In addition to the sheer number of doses likely to be needed, there are a host of logistical issues and supply challenges that come with the effort to distribute COVID-19 vaccines, including:

- The actual set of sites where vaccines will be administered, especially for the earliest phases of distribution, remains unclear. Federal guidance and operational plans indicate that it will be a mix of providers (such as hospitals and medical practices), pharmacies, state and local public health departments, and potentially government-run mass vaccination sites. Thousands of specific partners and site locations will have to be identified (and in some cases created), vetted, and approved before vaccine doses can be distributed to them. The accessibility of these sites will have implications for equitable access to the vaccine, given that lower income individuals and people of color are more likely to face transportation/location-based barriers to health care.

- Existing state and local governmental distribution networks are primarily focused on delivering childhood, but not adult vaccines. Especially early on, adults will likely be the focus for COVID-19 vaccine distribution, and mass distribution of vaccines to adults has, in the past, proven more challenging than delivering to children. This is because there are fewer pre-existing relationships and networks through state and local governments for adult vaccinations. During 2009-2010, for example, state and local vaccine programs had to triple the number of providers they had a relationship with to be able to distribute 2009-H1N1 vaccines. Governments at all levels will likely have to significantly expand their distribution channels and partnerships for vaccine administration to reach target groups with a COVID-19 vaccine.

- There will be a need to account for flexibility in planning and implementation of distribution. As the CDC and HHS plan distribution plans already recognize, there will be few doses available early on in the distribution process, with the supply of vaccine extremely limited compared to the demand. This will mean the first doses will be rationed, and that roll out will occur with unpredictable timing, as vaccine doses become available as production expands. Therefore, it will be important to set realistic expectations on initial supply. The effort to roll-out the 2009 H1N1 pandemic influenza vaccine lost credibility among state and local officials and the public alike when the amount of vaccine available to the public in October 2009 did not meet the earlier expectations that had been set by federal officials.

- Several of the likely COVID-19 vaccine candidates need to be preserved at extremely cold temperatures, which will require specialized equipment not currently available in many distribution sites. Urban areas, where specialized equipment is more likely to be present, will likely be able to manage cold chain supply processes more easily than rural areas where the equipment may not be available, which could introduce inequities in distribution. The federal government has stated it would likely not require jurisdictions to procure additional equipment but could implement a distribution approach that involved distributed networks of federally managed cold chain sites and use of mass vaccination to reach target populations.

- Several leading vaccine candidates will require two doses for immunization, with the second dose given several weeks after the first, which raises additional challenges. Vaccines with two-dose regimens will require careful tracking of doses and follow up with each individual receiving the vaccine to ensure they receive the same vaccine, with the second dose given at the proper time. This kind of two-dose schedule has not been required for other mass-distributed vaccines such as seasonal influenza or during the 2009-H1N1 pandemic influenza. The CDC and local jurisdictions are in the process of implementing a new vaccine tracking system to monitor COVID-19 vaccine administration and help with multiple dose tracking, but it is unclear if, or how, the new system will integrate with existing immunization information systems (IIS). There is already great variation in IIS across jurisdictions, and many have gaps and face other challenges including low provider participation rates and lack of interoperability of immunization records with patients’ electronic health records and across jurisdictional borders.

- Vaccines may be released on an accelerated schedule, and some may be administered under an EUA without having gone through a full safety review initially, so the government is planning on implementing enhanced safety monitoring to track vaccine adverse events. Close tracking of safety and adverse events is yet another layer of planning and administration falling primarily on state and local health authorities. Tracking adverse events closely will be important not only to determine the safety of the vaccines, but also to establish evidence of harm in individuals for potential compensation purposes. Under the liability protections outlined in the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness (PREP) Act manufacturers cannot be held liable for damages caused by their vaccines (except where there has been willful misconduct). However, individuals who die or suffer serious injuries directly caused by the administration of an approved vaccine under conditions of a public health emergency could receive compensation from the government through the Countermeasures Injury Compensation Fund (CICF), although there are some limitations to the CICF.

- Given that demand will be high and supply low during the initial phase of distribution, vaccine doses will be seen as highly valuable and therefore vulnerable to theft, fraud or corruption. This means physical security and close tracking of the shipments of doses will be required to ensure that vaccine doses get to delivered and administered properly, a level of planning and oversight beyond what is normally needed for vaccine distribution.

Federal, State, and Local Authority Over Vaccine Requirements

There remain outstanding issues concerning the relative roles and responsibilities of the federal, state and local governments in distributing a vaccine, as well as those of private actors. While much of the responsibility in the U.S. for delivering public health services, including support for vaccination, lies at the state and local levels, other considerations may be warranted in the midst of a pandemic that has been declared a national emergency. Federalism has benefits for public health, particularly the ability to localize responses, but raises unique challenges in a pandemic, with the potential for a complicated patchwork of different rules and regulations to navigate across jurisdictions, which could result in different timetables for receiving and shipping vaccines to providers, different levels of success in reaching target outcomes across the country, and differential access by geography, which could exacerbate existing inequalities in access and care and ultimately have implications for public health and broader population immunity. As one example, adult coverage rates for seasonal influenza, an ACIP-recommended vaccine that is free for most with insurance, vary by state, ranging from a low of 25% in Nevada to a high of 51% in Rhode Island (among those ages 18-64).

More specifically, some of the policy considerations around federal and state responsibilities include:

- Vaccine mandates: Governmental vaccine mandates play a role in the distribution and uptake of many vaccines, but the extent to which mandates can and will be used by federal, state, and local authorities to encourage COVID-19 vaccinations remains an open question. There are potential mechanisms by which federal authority could impose vaccine requirements such as though conditioning some forms of federal funding on vaccination, but there is a debate about how far federal powers extend here and whether the government should use these authorities for COVID-19 vaccines. On the other hand, state and local jurisdictions commonly impose vaccine mandates and could use their authorities to impose COVID-19 vaccination mandates, but this might mean requirements would vary greatly across jurisdictions.

- All states have immunization requirements in one form or another for child-care and school-age children, although there is significant variation across states (see Table 3). In many cases states mandate a set of vaccinations for children, allowing exemptions from this requirement only under certain circumstances. For example, some states allow only medical exemptions from vaccine requirements, while others allow medical as well as non-medical exemptions under some circumstances.

- Seasonal influenza vaccinations are typically not mandated by states, though some have taken steps toward such mandates. In August, Massachusetts announced it would require children in daycares and schools to receive a seasonal influenza vaccination this year; other states could follow. In 2009-2010 there were no state-level mandates requiring that children or adults receive a 2009-H1N1 influenza vaccine.

- Some states also mandate vaccines for certain types of health care workers, such as those working in hospitals or long-term care facilities. State laws vary considerably in terms of which vaccines are required, which types of workers the mandates cover, and what types of exemptions from these mandates are allowed. In the future, similar mandates could be developed by states for COVID-19 vaccines.

- States have additional authorities to mandate vaccinations during public health emergencies and outbreaks, often with the power to order such actions resting with the governor of the state or with a state health officer. For example, following a measles outbreak in 2019, New York City declared a public health emergency and used its expanded authority to requirethat individuals in certain zip codes to be vaccinated for measles. The differential application of these expanded authorities by states could introduce further inequities in vaccine coverage.

- Finally, in some cases, the private sector may mandate vaccination as a condition of employment, such as a hospital mandating vaccination for its health care workers. More generally, the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has taken the position that employers can require employees to be vaccinated for influenza, though exemptions may be provided. The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) states that employers should consider encouraging, rather than requiring, vaccination and, if vaccination is required, employees may be entitled to exemptions. Given the gravity of COVID-19, it is possible that employers will seek to mandate vaccination in some cases.

| Table 3: State Mandates for ACIP-Recommended Pediatric Vaccines | |

| Vaccine | Number of States with Mandate |

| Influenza | 5 states* |

| DTaP/Tdap | 50 states and DC |

| MMR | 50 states and DC** |

| Polio | 50 states and DC |

| Chicken pox | 50 states and DC |

| Hepatitis A | 17 states and DC |

| Hepatitis B | 46 states and DC |

| HPV | 3 states and DC |

| Meningococcal | 29 states and DC |

|

NOTES: DTaP/Tdap: tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis; MMR: measles, mumps, rubella; HPV: human papillomavirus

*CT, NJ, PA, and RI only require annual flu shots in childcare settings; MA requires of all children.

**IA does not require a mumps vaccine

SOURCE: KFF analysis of Information from state statutes and immunization websites. |

|

- Scope of practice regulations for vaccine administration. A key issue to consider concerns regulations around who can administer vaccines. Licensing of providers who can administer vaccines is determined at the state level, and therefore varies across the country. Expanding this scope of practice is one avenue for increasing distribution channels and uptake. Medical providers, such as physicians and nurses, commonly administer vaccines, but pharmacists can also administer many vaccines. State requirements around pharmacist administration of vaccines vary, particularly around which vaccines can be administered, what kind of training is needed to be licensed, and what for what ages pharmacists can vaccinate. During a public health emergency states can expand scope of practice laws, as several states did during the H1N1 pandemic in 2009-2010, but this can lead to differences across states. During a public health emergency, the federal government also has authority to expand scope of practice regulations under the PREP Act, and HHS has already done so to authorize pharmacists to order and administer childhood vaccines to individuals ages three through 18 years and to procure and administer COVID-19 vaccines when they become available. The COVID-19 vaccine authorization specifically preempts any state or local law that would prohibit these providers from administering vaccines, if the providers satisfy the requirements laid out in the guidance. States, and the federal government, could consider further expansions of scope of practice to accommodate the scale of COVID-19 vaccination requirements, if needed.

Insurance Coverage and Out-of-Pocket Costs

Ensuring that COVID-19 vaccines are available at no-cost to individuals would greatly enhance access. Both the Administration and Congress have taken steps to address this issue. The OWS strategy states that the Administration’s advance purchase of millions of doses of COVID-19 vaccines candidates from multiple manufacturers is intended to ensure that no American will be charged for the vaccine or its administration (although it is possible that some vaccine providers may still charge an administration fee). The Families First Coronavirus Response Act and the CARES Act put specific requirements in place for no-cost COVID-19 vaccine access under private insurance, Medicaid, and Medicare. These build on existing protections provided under the Affordable Care Act (ACA). However, despite these measures, limitations and gaps related to a COVID-19 vaccine remain, and some individuals, particularly adults, may still face cost and access barriers. Some of the key provisions and outstanding issues include:

- Private Insurance: Under federal legislation, most private insurers will be required to cover COVID-19 vaccines at no-cost. The ACA requires private health insurers to cover any vaccine recommended by ACIP at no-cost, although insurers have up to one year from the time of recommendation to implement coverage. The CARES Act specifically requires group health plans and health insurance issuers (those subject to ACA requirements for preventive services, but not including short-term limited duration or association health plans) to cover any ACIP-recommended COVID-19 vaccine without cost-sharing, including the cost of administration. Such coverage must begin 15 business days after an ACIP recommendation, which eliminates the usual up to one-year timeframe. However, these cost protections are not necessarily available if a patient seeks a vaccine from an out-of-network provider.

- Medicaid. All children and some adults in Medicaid have coverage for vaccines at no cost, and Congress has temporarily addressed the gap for other adults to ensure coverage for a COVID-19 vaccine. The ACA requires Medicaid coverage of all ACIP-recommended vaccines at no-cost for adults in the Medicaid expansion population. However, for adults covered through traditional Medicaid pathways, immunizations are an optional Medicaid benefit and, when covered, cost-sharing may be imposed. Currently, less than half of states cover all ACIP-recommended adult immunizations. The Families First Act addressed this by authorizing a 6.2 percentage point increase in federal Medicaid matching funds to help states respond to COVID. As a condition of receiving these enhanced funds, states must cover COVID-19 vaccines without cost-sharing, during the public health emergency. When the public health emergency declaration ends, however, adults in traditional Medicaid could face cost-sharing or may not have coverage for the vaccine. For children, Medicaid covers vaccines at no-cost through the Vaccines for Children Program (VCP), a 100% federally funded entitlement program created by Congress in 1993. The VCP also provides no-cost vaccine coverage for American Indian and Alaskan Native children, uninsured children, and children who meet the program’s criteria for being underinsured. In addition, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) also provides vaccine coverage for its enrollees, uninsured children who have incomes above Medicaid eligibility levels.

- Medicare. Vaccines are covered through Medicare, but some beneficiaries may face cost-sharing or delayed access for a COVID-19 vaccine, depending on the process used by FDA to make a vaccine available for use. Medicare covers vaccines under Parts B and D, with most vaccines covered under Part D. Part D plans must cover all FDA-approved vaccines, although they may impose cost-sharing. The CARES Act requires Medicare Part B to cover a COVID-19 vaccine and its administration without cost-sharing upon licensure by the FDA; this applies to beneficiaries in both traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage plans. It does not, however, require such coverage upon issuance of an EUA, which could limit access to vaccines for the more than 60 million people covered by Medicare if a vaccine first becomes available via an emergency authorization.

- Uninsured and underinsured adults: There is no federal entitlement vaccination program for uninsured and underinsured adults. Instead, existing federal programs that support vaccination for the uninsured and underinsured are discretionary and rely on annual Congressional appropriations for funding. These include Section 317 of the Public Health Service Act, which authorizes the federal purchase of vaccines for uninsured or underinsured adults (as well as children and adolescents), and can be used during an outbreak, and funding for FQHCs, which provide vaccinations regardless of ability to pay. During H1N1, the federal government purchased the vaccine and funded public health authorities to ensure that uninsured and underinsured adults received it free of charge, as long as they were vaccinated at a public health clinic or other designated site. Similarly, it is expected that the federal government’s purchase of COVID-19 vaccines will be used to support free vaccination of adults who are uninsured and underinsured. Funds to providers to cover vaccine administration costs will be available through a “COVID-19 claims reimbursement program”, part of a new Provider Relief Fund created and funded through the CARES Act and the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act. Despite these measures, it is not yet known if the existing advance purchase of COVID-19 vaccines or the claims reimbursement program will be sufficient to support vaccination for all those who are uninsured and underinsured, and whether additional funding or other remedies might be needed.

Addressing Racial and Ethnic Disparities

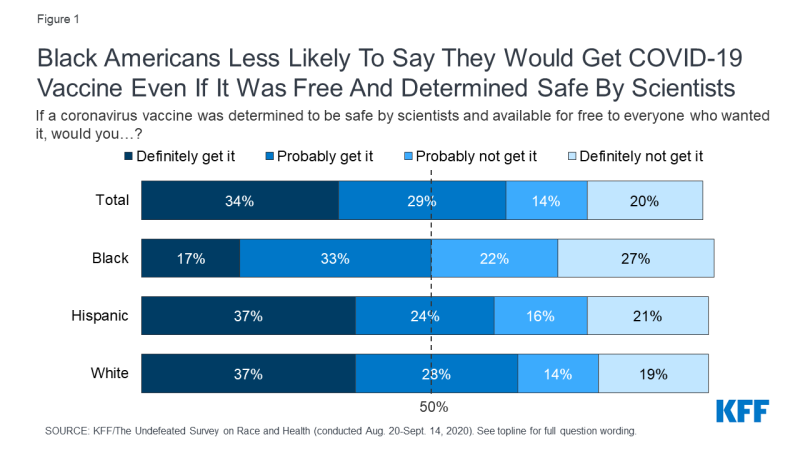

COVID-19 has had a significant impact on communities of color in the U.S., who account for a disproportionate share of COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths. Data also indicate that the pandemic is taking a larger economic toll on communities of color, and that COVID-19 threatens to further widen racial and ethnic disparities that already exist in the U.S. Moreover, the medical system’s historic mistreatment of people of color and ongoing racism and discrimination contribute to greater distrust among communities of color that may contribute to increased reluctance to be vaccinated. A new KFF/The Undefeated survey, for example, found that half of Black adults say they would not want to get a coronavirus vaccine even if deemed safe by scientists and freely available, with safety concerns and distrust cited as the top reasons (see Figure 1). By contrast, most White adults say they would get vaccinated, and those who wouldn’t are more likely to say they don’t think they need it. In addition, the survey found that majorities of Black adults lack confidence that the vaccine development process is taking the needs of Black people into account, and that when a vaccine becomes available it will have been properly tested and will be distributed fairly. Already, there are significant disparities in adult vaccine coverage rates for racial and ethnic minorities in the context of routine immunization. For example, coverage rates for seasonal influenza, which is available at no-cost to those with insurance, are lower for adults of color compared to Whites. Coverage rates by race/ethnicity also vary by state. Taken together, these issues present formidable challenges not only to reaching people of color with a COVID-19 vaccine, but to the success of the overall national COVID-19 vaccine effort. Ultimately, effective outreach strategies developed in partnership with and directed toward communities of color will be critical to building public trust and willingness to get vaccinated.

Figure 1: Black Americans Less Likely To Say They Would Get COVID-19 Vaccine Even If It Was Free And Determined Safe By Scientists

Communication and Trust

Except when individuals may be subject to a vaccine mandate, receiving a COVID-19 vaccine will be voluntary. Therefore, achieving high vaccination rates and sufficient population-level protection from the virus will depend on the public’s willingness to be vaccinated: people will have to trust the vaccine, the authorities overseeing distribution, and the provider administering the vaccine. All vaccines face issues of public confidence to one extent or another, yet there are indications that distrust of COVID-19 vaccines (despite the fact that no vaccine has been approved yet) may be even greater than for other vaccines. This presents a significant challenge for authorities at the federal, state, and local levels, and will require robust communication and trust-building efforts to address.

- The most common reasons given by adults for not receiving seasonal influenza vaccines are concerns about the safety and efficacy of the vaccine and a belief the vaccine itself can make a person ill.

- Polling on COVID-19 vaccines has indicated an increasing level of mistrust about the vaccines and decreasing willingness among Americans to receive one. In May, 72 percent of U.S. adults said they would definitely or probably get a vaccine to prevent COVID-19 if it were available but in September only 51 percent said the same (a 21 percent decline in four months). Partially driving this growing distrust among Americans is an increasing concern with politicization of the vaccine approval process: a majority of the public (62 percent) is worried political pressure will lead the FDA to rush to approve a coronavirus vaccine without making sure that it is safe and effective. As noted above, Black adults in particular have expressed some of the highest levels of mistrust of COVID-19 vaccines even as this group has been disproportionately affected by the pandemic.

- Reducing mistrust about COVID-19 vaccines would involve a multi-pronged communication approach, including efforts to counter the growing public perception that politics is driving the vaccine approval process for COVID-19 to ensure Americans have confidence that when a vaccine is approved that they believe it is indeed safe and effective. A recent letter from the HHS National Vaccine Advisory Committee to the Assistant Secretary for Health included recommendations for building public confidence, including through a unified, proactive, and highly visible, communication structure and community and stakeholder engagement. Transparency and avoiding conflicts of interest helps in reducing mistrust. In addition, having clear, consistent, and culturally-relevant messages about COVID-19 vaccines and their benefits to individuals, communities, and the country will be important, as will building partnerships in advance with individuals and groups that can serve as trusted sources for delivering such messages for different communities. Given that safety of vaccines has been the number one concern both in past vaccination campaigns and regarding COVID-19 vaccines, a particular emphasis on assuring safety will be important.

Conclusion

There is no doubt that distributing COVID-19 vaccines will be a massive, complicated effort for the U.S., and an unprecedented challenge for officials at the federal, state, and local levels. While planning for distribution has been underway for months and progress has been made, there are still numerous questions about how the U.S. will plan to overcome the many challenges. An undertaking of this magnitude also means that no plan will unfold exactly as expected and there will inevitably be substantial learning and the need to make adjustments made as implementation unfolds. Adding further uncertainty to this effort is the fact the U.S. is currently in the midst of election season, and its possible there might be significant changes in federal, state, and local government leadership just as the distribution of COVID-19 vaccines gets underway. Successfully addressing the barriers and challenges identified here will be important in the effort to ensure the greatest health benefit accrues from administering COVID-19 vaccinations.