Current Flexibility in Medicaid: An Overview of Federal Standards and State Options

Executive Summary

Key Takeaways

This brief provides an overview of current federal standards and state options in Medicaid to help inform upcoming debates about increasing state flexibility in the program as part of efforts to restructure Medicaid financing.

- Today, states operate their Medicaid programs within federal standards and a wide range of state options in exchange for federal matching funds that are provided with no limit.

- Each state Medicaid program is unique, reflecting states’ use of existing flexibility and waiver authority to design their programs to meet their specific needs and priorities.

- As proposals to restructure Medicaid financing develop, it will be important to examine what additional flexibilities they would provide to states and what standards, accountability and enrollee protections would remain for states to access federal funds.

Executive Summary

The Trump Administration and Republican leaders in Congress have called for fundamental changes in Medicaid financing that would limit federal financing for Medicaid through a block grant or per capita cap. Such changes may be tied to offers of increased flexibility to states to manage their programs within a more limited financing structure. Which federal standards would remain in place and what increased flexibility might be provided to states would have significant implications. To help inform discussion around increased flexibility, this brief provides an overview of current federal standards and state options in Medicaid and how states have responded to these options in four key areas: eligibility, benefits, premiums and cost sharing, and provider payments and delivery systems.

Today, states operate their program within federal standards and a wide range of state options in exchange for federal matching funds that are provided with no limit. Medicaid is jointly financed by the federal government and states, with the federal government providing federal matching funds for allowable state Medicaid spending on an open-ended basis. In exchange for the federal funds, states must meet federal standards that reflect the program’s role covering a low-income population with limited resources and often complex health needs. The federal standards largely focus on requiring states to cover certain core groups, such as poor children and pregnant women, as well as certain core benefits. However, states can choose to cover additional groups and benefits and have wide latitude over many aspects of the program, particularly how they pay providers and structure their delivery systems. Moreover, states can use Section 1115 waiver authority to vary from the federal standards and state options to address different priorities and emerging issues.

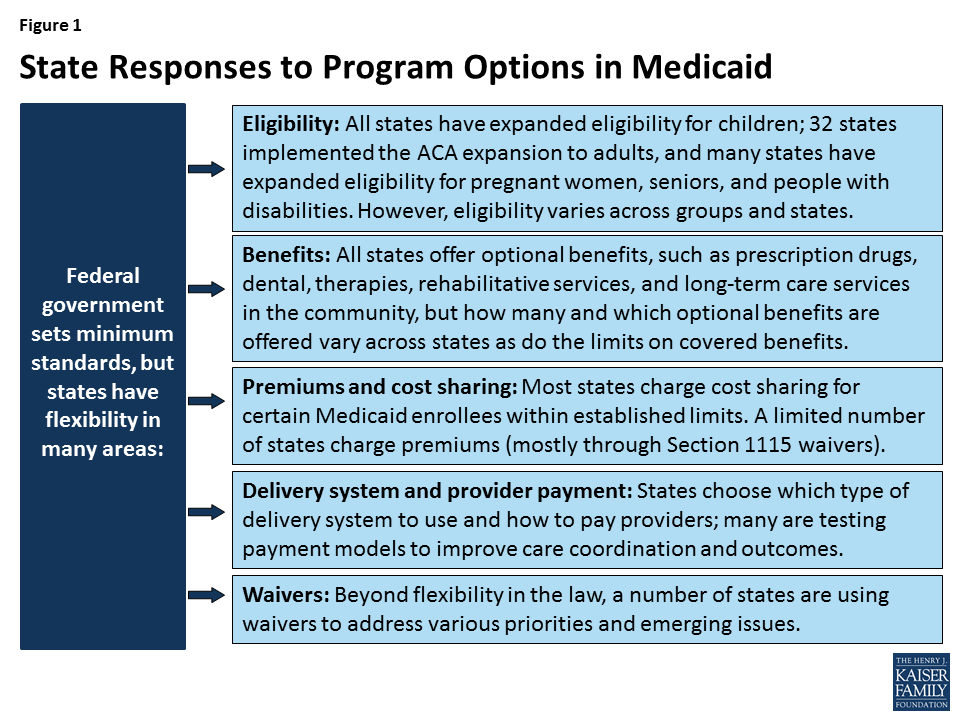

Each state Medicaid program is unique, reflecting states’ use of existing program flexibility and waiver authority to design their programs to meet their specific needs and priorities. The programs vary widely in terms of who is eligible, what benefits are covered, what premiums and cost sharing are charged, and how providers are paid and care is delivered (Figure 1). Over time, many states have expanded Medicaid to reach a greater share of their low-income population through both targeted and broad expansions. States also have used program flexibility to continually evolve and transform how they pay for and deliver care. Further, during economic downturns, states have used options to cut provider rates and restrict benefits to control Medicaid spending.

As proposals to restructure federal Medicaid financing develop, it will be important to examine what additional flexibilities they would provide to states and what standards, accountability and enrollee protections would remain for states to access federal funds. As noted, states have broad flexibility over many aspects of their programs and can gain increased flexibility under Section 1115 waiver authority. What additional flexibilities would be provided beyond these options under such proposals would have implications for states, enrollees, and providers. What federal standards would remain in place will affect the extent of accountability for the federal investment in the program and the scope of nationwide protections available for enrollees. Additionally, how such proposals would address existing program variation in establishing base levels for the caps will be key, including variation as a result of 32 states, including DC, adopting the ACA expansion. Setting the caps based on current spending could lock historical state choices and program variation in place potentially rewarding states with higher historic spending and creating “winners” or “losers” across states.

Issue Brief

Introduction

Medicaid is jointly financed by the federal government and states. The federal government provides matching dollars to states for allowable spending on Medicaid on an open-ended basis.1 In exchange for the significant federal investment in the program, states design and administer their programs within a set of federal standards and broad state options defined by law that reflects the program’s role covering a low-income population with limited resources and often complex health needs. Beyond these options, federal law also authorizes the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) to waive certain Medicaid requirements and to provide federal Medicaid funding for options not otherwise allowed under law for approaches the Secretary determines promote the objectives of the program.

The Trump Administration and Republican leaders in Congress have called for fundamental changes in Medicaid financing that would limit federal financing for Medicaid through a block grant or per capita cap. Such changes may be tied to offers of increased flexibility to states to manage their programs within a more limited financing structure. Which federal standards would remain in place and what increased flexibility might be provided to states would have significant implications. To help inform discussion around increased flexibility, this brief presents an overview of current federal standards and state options within Medicaid in four areas: eligibility, benefits, premiums and cost sharing, and provider payments and delivery systems.

The Upcoming Debate around Flexibility

President Trump and other Republican leaders have called for providing states with increased flexibility in how they operate their Medicaid programs. In December, Republican Leaders in the House of Representatives and Republican Members of the Senate Finance Committee sent letters to Governors and Insurance Commissioners to request information about health care reforms including a focus on Medicaid. In January, Republican Chairmen from the Senate Finance Committee and House Energy and Commerce Committee sent a letter to the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) requesting detailed information on Medicaid optional benefits and populations covered in each state to inform debate around controlling Medicaid spending. Previous analysis conducted prior to the ACA showed that 60% of total Medicaid spending is for optional eligibility groups and optional services for all groups and that some of the sickest enrollees fall into optional groups and many optional benefits, such as prescription drugs, are integral to comprehensive coverage. The share of spending that goes toward optional groups and benefits has likely increased since this analysis was completed, as states have gained additional program options since that time.

Calls for increased Medicaid flexibility are not new, and the minimum standards and options have evolved over time through federal legislation. For example, the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 added more options for states to charge premiums and cost-sharing as well as increased flexibility around benefits. More recently, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the Supreme Court ruling on its constitutionality in 2012 provided new program flexibility around eligibility as well as for delivery system reform and new options for states to deliver community-based long-term care. Moreover, before the most recent Congressional letters, there were earlier efforts to expand state flexibility including the plan offered by Senator Hatch and Representative Upton in 2013 and the Republican Governors Public Policy Committee report in 2011 as part of block grant proposal debates. At the state level, trends over time show that states have used flexibility with the Medicaid program to different degrees. However, many states have used options to cover a greater share of their low-income population through targeted and broad expansions. States have also used available flexibility to continually evolve and transform how they how they pay for and deliver care. Further, during economic downturns, states have used options to cut provider rates and restrict benefits to control Medicaid spending.

Upcoming proposals for increased flexibility are anticipated to emerge within the context of reducing and capping federal spending by restructuring Medicaid financing to a block grant or per capita cap. However, previous analysis suggests that increased flexibility may only provide limited gains in program efficiencies, and that states would need to reduce enrollment or benefits to achieve large reductions in federal spending. For example, prior analyses examining block grant proposals released by House Republicans in 2011 and 2012 showed that even if states were able to limit per enrollee spending growth, the magnitude of the federal spending reductions would result in enrollment cuts of 42% to 50% accounting for the repeal of the ACA or 25% to 35% due to the block grant cuts; the analysis also showed reductions in reimbursement for providers including hospitals and nursing homes. Congressional Budget Office analysis from 2011 also noted that the large reduction in federal payments under the House Budget Plan would likely require states to reduce payments to providers, curtail eligibility for Medicaid, provide less extensive coverage to beneficiaries, or pay more in state funds than would be the case under current law. Moreover, the wide variation in spending across state programs resulting from current flexibility in the program creates challenges to establishing a block grant or per capita cap. Setting the caps based on current spending could lock historical state choices and program variation in place potentially rewarding states with higher historic spending creating “winners” or “losers” across states.

Minimum Standards and State Options

Eligibility

Minimum Standards

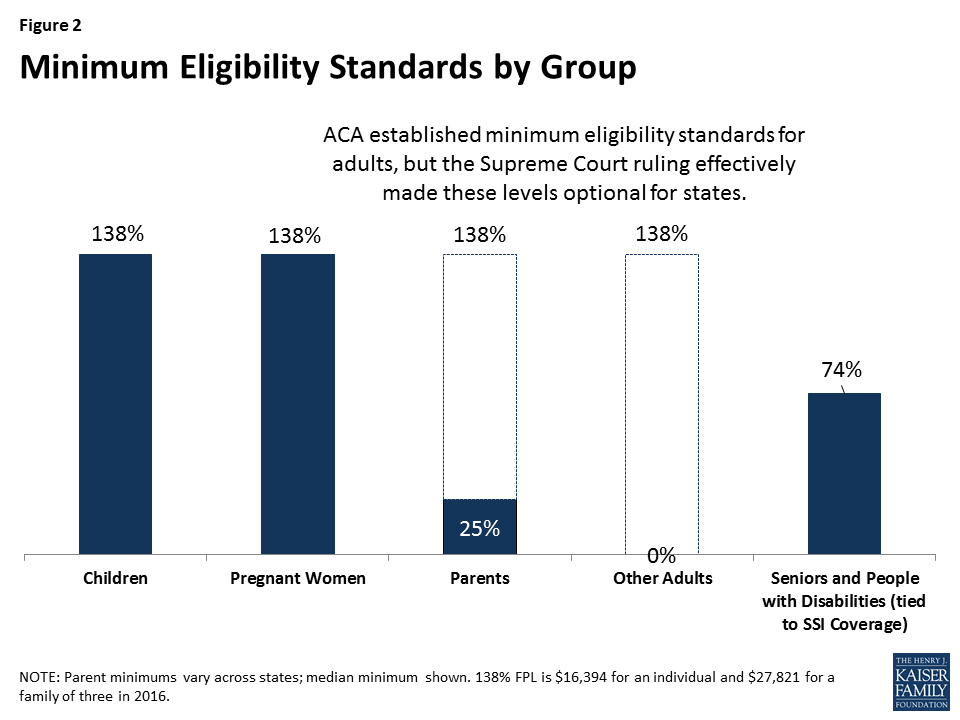

Minimum eligibility standards for pregnant women and children have expanded over time. At the Medicaid program’s outset in 1965, the minimum coverage groups were closely tied to welfare and included low-income families, seniors, and individuals with disabilities who were receiving cash assistance. Over time, the minimum coverage standards have expanded, particularly for children and pregnant women, largely following state adoption of options to expand coverage for these groups. Reflecting these expansions, prior to the ACA, states were required to cover children under age six and pregnant women with family incomes up to 133% FPL and older children with family incomes up to 100% FPL. The ACA built on these previous expansions by extending the 133% FPL minimum to older children. It also includes a five percentage point of income disregard that effectively raises the minimum to 138% FPL (Figure 2).2 As a result of this change, some states moved older children from separate CHIP programs to Medicaid. The ACA also established a maintenance of effort provision under which states must keep eligibility levels for children at least as high as they were when the ACA was enacted in 2010, until 2019.

Prior to the ACA, many low-income adults were excluded from Medicaid. Prior to the ACA, minimum eligibility standards for parents remained very low and there was no minimum or option to cover other low-income adults without dependent children. The ACA also expanded the 138% FPL minimum to adults, making many parents and other adults newly eligible for coverage.3 Although this expansion was enacted as a nationwide standard, the 2012 Supreme Court ruling on the ACA’s constitutionality effectively made the expansion to adults a state option.

The ACA did not change minimum eligibility standards for seniors and people with disabilities. States generally must cover seniors and people with disabilities receiving Supplemental Security Income (SSI)4 benefits (equivalent to 74% FPL, or about $8,800 per year for an individual, in 2017).5 States also must offer Medicare Savings Programs through which low-income Medicare beneficiaries with incomes generally below 135% FPL (or about $16,000 per year for an individual in 2016) receive Medicaid assistance with some or all of their Medicare premiums, deductibles, and other cost-sharing requirements (these “partial dual eligible” beneficiaries do not receive Medicaid benefits). Medicare has high out-of-pocket costs, and through the Medicare Savings Programs, Medicaid helps make Medicare affordable for those with the lowest incomes.6

State Options

Before the ACA, states could expand eligibility beyond the minimum levels for children, pregnant women, parents, seniors, and individuals with disabilities and receive federal Medicaid matching funds. The creation of the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) in 1997 provided states additional options and enhanced federal funding to expand coverage for children. However, prior to the ACA, there was no option for states to cover low-income adults who did not fit into one of these categories, regardless of their income. As such, states could not receive federal funds to cover these adults, unless they received a waiver of federal rules and found offsetting savings to fund their coverage. As a result of the ACA expansion, states can now cover low-income adults up to 138% FPL and receive enhanced federal matching funds for this coverage. States also can choose to cover children, pregnant women, and other adults beyond the ACA’s 138% FPL minimum and receive federal funds for this coverage at their regular matching rate.

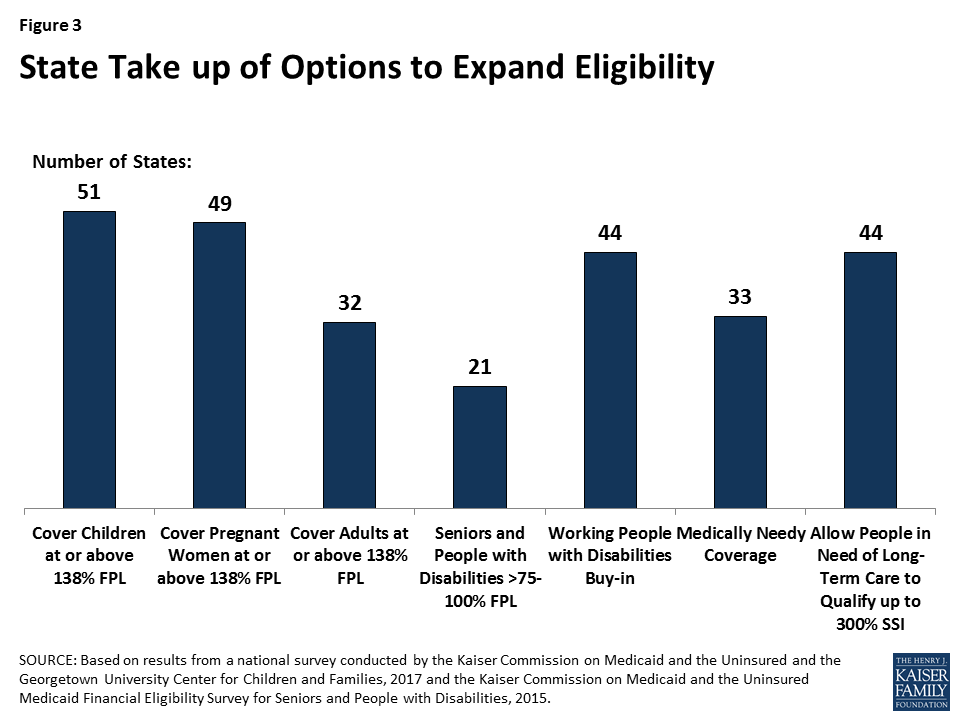

All states have taken up options to expand eligibility for children and many have expanded eligibility for pregnant women and other adults. As of January 2017, all states expanded eligibility for children above the 138% FPL minimum with 49 states setting eligibility for children at 200% FPL or higher through Medicaid and CHIP. Forty-nine states cover pregnant women above the federal minimum with 32 states setting eligibility at 200% FPL or higher (Figure 3). A total of 32 states, including DC, have taken up the ACA option to expand Medicaid to low-income adults with incomes up to 138% FPL, and three states extend coverage to parents and/or other adults at higher incomes. However, in the 19 states that have not expanded, eligibility limits for parents remain very low, with a median of 44% FPL, and other adults are not eligible regardless of income in all but one of these states.

All states have expanded coverage for seniors and people with disabilities, with most states electing multiple coverage options. As of 2015, 21 states have increased eligibility for seniors and individuals with disabilities above the SSI level up to a federal maximum of 100% FPL; states also may apply an asset limit to this pathway, and all but one do. Nearly all states offer an eligibility pathway for children with significant disabilities living at home without regard to parental income who would be Medicaid-eligible if institutionalized.7 Thirty-three states chose to offer medically needy coverage, which enables people with high medical bills to spend down to a state-set eligibility standard.8 Forty-four states allow working individuals with disabilities with income above eligibility limits to buy into Medicaid, and five states offer a buy-in for children with significant disabilities with household income up to 300% FPL ($60,480 per year for a family of 3 in 2016).

States also can expand access to coverage for individuals with long-term care needs. In addition to the age and disability-related eligibility pathways above, states can offer Medicaid to people who need institutional or community-based long-term care with incomes up to 300% of SSI ($26,388 per year for an individual in 2016). States also set the asset limits to qualify for long-term care services. As of 2015, 44 states allowed people in need of nursing facility care to qualify for Medicaid with income up to 300% of SSI, and nearly all of these states use the same expanded financial eligibility standard for people receiving long-term care in the community. Moreover, states can expand Medicaid functional eligibility criteria to cover people with functional needs that do not yet meet an institutional level of care through the Section 1915 (i) state plan option. This option allows enrollees to remain in their homes and helps prevent the need for more intensive and costly services in the future. As of 2015, 17 states elected the Section 1915 (i) option to provide home and community based services (HCBS) to people at risk of future institutionalization.9 States have most frequently targeted this option to adults and children with significant mental health needs and people with intellectual or developmental disabilities.

Benefits

Minimum Standards

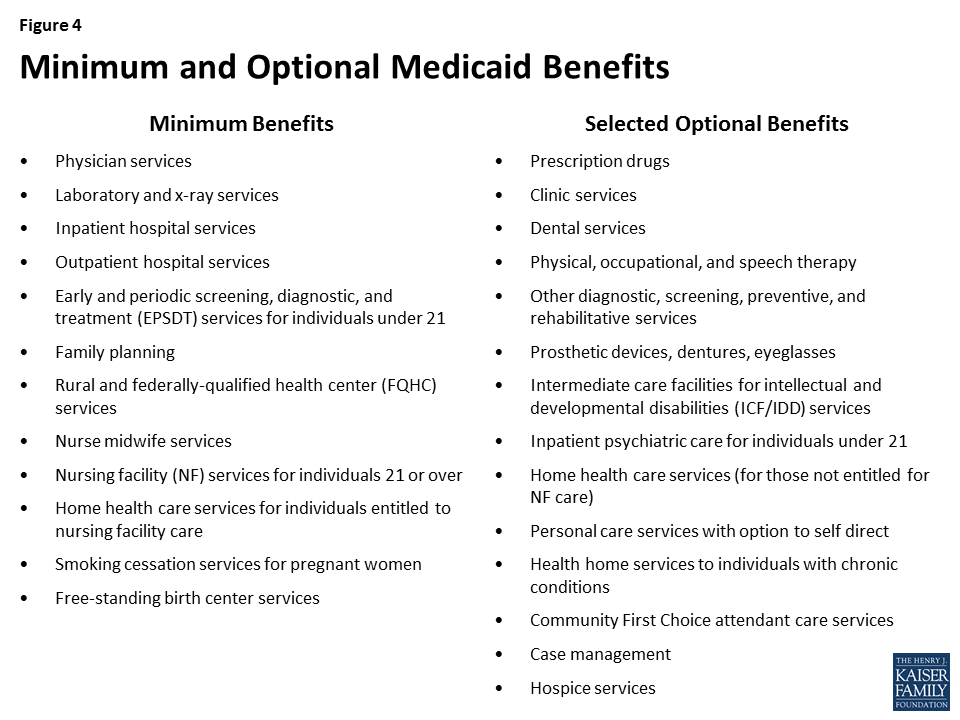

Federal standards outline minimum benefits for states to cover through their state Medicaid benefit package (Figure 4). For children, the minimum Medicaid benefit package offers access to all necessary services through the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit, which includes regular screenings, vision, dental, and hearing services and any other medically necessary care. For adults, minimum benefits include services such as those provided by physicians and hospitals. The ACA added some new minimum benefits including smoking cessation services for pregnant women and free-standing birth center services. Although states must cover these minimum benefits, they determine the amount, duration, and scope of this coverage. Other services that are important for comprehensive care, such as prescription drugs, are not included in the minimum benefit package for adults.

Federal minimum long-term care benefits include nursing facility services and home health services for those who qualify for nursing facility services. There is no minimum standard for states to provide coverage for home and community-based care beyond the home health benefit in the Medicaid program. However, under the 1999 Supreme Court decision, Olmstead v. L.C., the Justices ruled that, under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), institutionalizing a person with a disability who can benefit from and wants to live in the community is illegal discrimination.

State Options

Reflecting the diverse health needs of enrollees, there is a broad range of optional benefits that states may choose to cover and for which they may receive federal matching funds. Many of these optional benefits include long-term care services and supports that are not typically included in private insurance plans. For both minimum and optional benefits, states determine the amount, duration, and scope of covered benefits (e.g., the number of covered visits), subject to the requirement that coverage of the benefit be sufficient to achieve its purpose. All states offer at least some optional benefits, including prescription drugs, but how many and which optional benefits are offered vary across states as do the limits on covered benefits. The ACA created a new optional health home benefit to provide coordinated care to individuals with chronic conditions; states can receive a 90% federal match for the first two years that they offer this benefit.10 In 2016, 21 states (including DC) had at least one Medicaid health home program in place.

States can choose to provide a range of optional HCBS.11 Some of these include personal care services, offered by 32 states in 2013, and Community First Choice (CFC) attendant care services and supports, offered by eight states as of 2016. CFC is a new option added by the ACA that offers enhanced federal matching funds. In recent years, states also have been adding services such as supportive housing and supported employment to help people with disabilities function independently in the community. States also have the option to allow beneficiaries to self-direct their services by selecting and dismissing workers and/or allocating dollars within their service budgets. States have used the Medicaid HCBS options to shift the balance of long-term care spending away from institutions and toward community-based care. The share of Medicaid LTSS spending devoted to HCBS increased from 18% in 1995 to 53% in 2014.12 These options have also helped states meet their Olmstead obligations under the ADA by providing services that help people with disabilities live independently in the community.

States may provide some groups with “alternative benefit plans” (formerly called “benchmark benefit packages”) instead of the traditional state Medicaid benefit package. This option was established in the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 (DRA), which also newly allowed states to vary the benefits provided by coverage group or geographic area within the state.13 States can choose to base their alternative benefit plans on the standard Blue Cross Blue Shield (BCBS) preferred provider plan under the Federal Employees Health Benefits Plan (FEHBP), a state employee plan, the state’s largest commercial health maintenance organization (HMO), or other Secretary-approved coverage.14 Very few states have used this DRA option for benefits. The ACA requires that states provide expansion adults with an alternative benefit plan, but nearly all states have aligned their expansion adult benefit package with the benefit package provided to other enrollees for ease of administration and to provide equitable coverage across populations.

States also may use Medicaid funds as premium assistance to purchase private insurance rather than providing direct coverage. Medicaid premium assistance programs must be cost-effective and provide wraparound coverage so that enrollees have access to the same benefits and cost sharing protections as they would under traditional Medicaid coverage. Most states operate a premium assistance program, but enrollment in these programs is relatively low.15 This low enrollment reflects the limited availability of employer-sponsored coverage among the low-income population. More recently, Arkansas and New Hampshire are using the Medicaid premium assistance option to purchase Marketplace coverage for their ACA expansion adults.16

Premiums and Cost Sharing

Minimum Standards

Federal standards exempt certain groups and services from premium and cost sharing charges to prevent cost barriers to coverage and care for the lowest income Medicaid enrollees. States may not charge premiums to Medicaid enrollees with incomes below 150% FPL. States cannot charge cost-sharing for emergency, family planning, pregnancy-related services, preventive services for children, or preventive services defined as essential health benefits in alternative benefit plans in Medicaid. In addition, children with incomes below the minimum eligibility standard generally cannot be charged cost-sharing.

State Options

States may charge premiums and cost sharing for certain Medicaid enrollees within established limits. The DRA gave states new options to charge premiums and cost sharing, which vary by group, income, and service.17 States may charge premiums for enrollees with incomes above 150% FPL. States also may charge cost sharing, but allowable charges vary by income (Table 1). Regardless of income, aggregate out-of-pocket costs for an individual may not exceed 5% of family income. The DRA also allowed states to make premiums and cost sharing enforceable for certain enrollees, meaning that individuals over 150% FPL can be disenrolled from coverage due to unpaid premiums, and a state can allow providers to deny care (other than emergency services) to those above poverty, unless an individual makes a required copayment at the point of service.18

| Table 1: Maximum Allowable Cost Sharing Amounts in Medicaid by Income | |||

| <100% FPL | 100% – 150% FPL | >150% FPL | |

| Outpatient Services | $4 | 10% of state cost | 20% of state cost |

| Non-Emergency use of ER | $8 | $8 | No limit (subject to overall 5% of household income limit) |

| Prescription Drugs Preferred Non-Preferred | $4 $8 | $4 $8 | $4 20% of state cost |

| Inpatient Services | $75 per stay | 10% of state cost | 20% of state cost |

| NOTES: Some groups and services are exempt from cost sharing, including children enrolled through mandatory eligibility pathways, emergency services, family planning services, pregnancy-related services, and preventive services for children. Maximum allowable amounts are as of FY2014. Beginning Oct. 1, 2015, maximum allowable amounts increase annually by the percentage increase in the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U). | |||

Premium and cost sharing charges in Medicaid vary across states and eligibility groups. As of January 2017, four states charge premiums and three states charge cost sharing for children in Medicaid. (A larger number of states charge children premiums or enrollment fees and cost sharing in CHIP because the program covers children with relatively higher incomes and has different premium and cost sharing rules.) Among adults, 39 states charge parents cost-sharing in Medicaid, and 23 of the 32 states that have expanded Medicaid charge cost-sharing for expansion adults. Cost sharing amounts for adults are generally nominal, reflecting the low incomes of adults covered by Medicaid. Similarly, because eligibility levels for parents and other adults are generally at or below 138% FPL, most states do not charge premiums for adults. However, six states (Arizona, Arkansas, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, and Montana) have received Section 1115 waiver approval to charge premiums or monthly contributions that are not otherwise allowed for their Medicaid expansion adults; these amounts are generally 2% of income, equivalent to what beneficiaries from 100-138% FPL would incur if they enrolled in Marketplace coverage.

Provider Payments and Delivery Systems

Minimum Standards

States have latitude to determine provider payments so long as the payments are consistent with efficiency, economy, quality and access and safeguard against unnecessary utilization. Within these broad guidelines, provider payments must be sufficient to ensure Medicaid beneficiaries with access to care that is equal to others in the same geographic area, and payments to managed care organizations must be actuarially sound.19 There are additional requirements that vary by provider type. For institutional providers such as hospitals and nursing facilities, states must publish payment methodologies for public review and comment and payments are subject to upper payment limits. States must pay federally qualified health centers and rural health clinics based on a prospective payment system that relies on costs in a base year, which are trended forward. Federal law requires that drug manufacturers enter into rebate agreements with the federal government to provide their drugs through Medicaid. Lastly, federal law requires that state Medicaid programs make Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments to qualifying hospitals that serve a large number of Medicaid and uninsured individuals. Within the annual DSH allotments to states and hospital specific limits, states have considerable flexibility on how to distribute DSH funds.

Federal standards do not address how states structure the delivery system used to provide services to Medicaid enrollees. However, if a state uses managed care, it must meet certain standards related to plan choice and provide certain consumer protections.

State Options

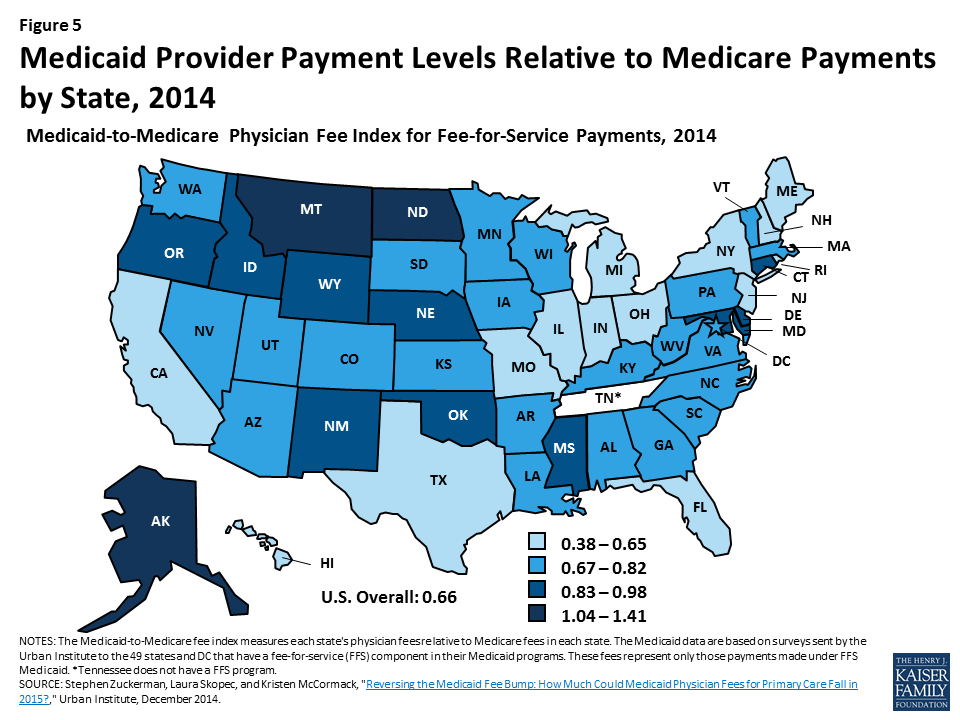

Given the broad authority available to states to set provider payments, there is significant variation across states in how provider rates are determined as well as in payment levels. States use a variety of payment methodologies for hospitals, including diagnosis related groups (DRGs) similar to Medicare, per diem amounts, or costs. Fee-for-service payments for physicians also vary significantly across states. For example, rates for office visits in California are 19% below the national Medicaid average while Oklahoma pays 29% above the average.20 On average, states pay fee-for-service providers about 66% of what Medicare pays, although this ratio differs across states (Figure 5). For managed care, some states set rates based on fee-for-service claims while others base rates on risk adjustments for different populations. Information is limited regarding the rates paid to providers in managed care.

States choose what type of delivery system to use to serve Medicaid enrollees. They can choose to serve enrollees through a fee-for-service system, a primary care case management model, or through capitated managed care plans. As of July 2016, 48 states had some form of managed care in place, including primary care case management and/or comprehensive risk-based managed care organizations (MCOs). Among the 39 states that contract with MCOs, 28 states reported that at least 75% of their enrollees were in MCOs, including four of the five states (California, New York, Texas, and Florida) with the largest total Medicaid enrollment across the country (Figure 6).

An increasing number of states are adopting capitated managed care models that integrate physical, behavioral health, and long-term services and supports. As of 2016, nearly half (24) states operate a capitated managed long-term care program for at least some seniors and people with disabilities.21 Other states are providing access to HCBS in fee-for-service delivery systems.

State Medicaid programs have been expanding their use of payment and delivery system reform models including patient-centered medical homes, health homes, ACOs, and episode of care payments. These initiatives may be implemented through fee-for-service or managed care. State innovation in delivery and payment systems has been influenced and catalyzed by new demonstration and pilot programs and state plan authorities provided by the ACA. The ACA established the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) to test, evaluate, and expand innovative care and payment models to foster patient-centered care, improve quality, and slow cost growth in Medicare, Medicaid and CHIP. CMMI launched the State Innovation Models (SIM) initiative which has awarded nearly $950 million in grants to states to design, implement, and evaluate multi-payer health care delivery and payment reforms aimed at improving the quality of care and health system performance while decreasing costs for Medicaid, CHIP, and Medicare beneficiaries.22 Many state Medicaid programs report adopting and promoting alternative provider payment models as part of their SIM projects.23 Additionally, 8 states’ Medicaid programs are participating in the CMMI Comprehensive Primary Care Plus (CPC+) initiative, a multi-payer advanced primary care medical home model.24

DEMONSTRATION AUTHORITY

State Options

Federal law also provides Section 1115 waiver authority, which allows the Secretary of HHS to waive certain requirements in Medicaid and to allow federal Medicaid matching funds for purposes not otherwise allowed under federal rules. This provision authorizes the Secretary to allow approaches that do not meet federal rules, as long as the Secretary determines that the initiative is a “research and demonstration project” that “furthers the purposes” of the program. While the Secretary’s waiver authority is very broad, there are some elements of the program that the Secretary does not have authority to waive, such as the federal matching payment system for states. As of January 2017, 37 states have 50 approved Section 1115 waivers.25 States have used Section 1115 waivers for many purposes, including to expand eligibility, change delivery systems, alter benefits and cost-sharing, modify provider payments, and quickly extend coverage during an emergency.

The ACA created an additional Section 1115A waiver authority. Using Section 1115A authority, CMS along with 13 states launched financial and administrative alignment demonstrations that seek to improve care and control costs for people who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid.

Looking Ahead

Debate around increased flexibility within Medicaid will likely emerge within the context of proposals to fundamentally restructure financing of the program to a block grant or per capita cap and reduce federal financing. Calls for increased Medicaid flexibility are not new, and the balance of standards and options has shifted over time. Today, states have broad flexibility over many aspects of their programs and can gain increased flexibility under Section 1115 waiver authority. What additional flexibilities would be provided beyond these options under such proposals would have implications for states, enrollees, and providers. What federal standards would remain in place will affect the extent of accountability for the federal investment in the program and the scope of nationwide protections available for enrollees. Additionally, how such proposals would address existing program variation in establishing base levels for the caps will be key, including variation as a result of 32 states, including DC, adopting the ACA expansion. Setting the caps based on current spending could lock historical state choices and program variation in place potentially rewarding states with higher historic spending and creating “winners” or “losers” across states.

Endnotes

- The federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP) is determined by a statutory formula based on state per capita income, which varies across states and adjusts over time. The federal government has temporarily increased the matching rate to provide fiscal relief to states during economic downturns and established an enhanced matching rate for some purposes, including the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Medicaid expansion to low-income adults. ↩︎

- The minimum is 133% of poverty, but the law includes a standard income disregard of five percentage points of the federal poverty level, which effectively raises this limit to 138% FPL. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- To be eligible for SSI, beneficiaries must have low incomes, limited assets, and an impaired ability to work at a substantial gainful level as a result of old age or significant disability. ↩︎

- As of 2015, 10 states elect the § 209(b) option to use disability or financial eligibility standards that are more restrictive than the federal SSI rules, so long as the state’s rules are not more restrictive than those in effect in January 1972. Section 209(b) states must allow SSI beneficiaries to establish Medicaid eligibility through a spend-down by deducting unreimbursed out-of-pocket medical expenses from their countable income. Section 209(b) states also must provide Medicaid to children who receive SSI and who meet the state’s financial eligibility rules for the AFDC program as of July 16, 1996. ↩︎

- There are 3 Medicare Savings Programs: Medicaid pays Medicare premiums and cost-sharing for Qualified Medicare Beneficiaries (up to 100% FPL). Medicaid pays Medicare premiums for Specified Low-Income Medicare Beneficiaries (100-120% FPL) and Qualified Individuals (up to 135% FPL). There also are asset limits for these programs. ↩︎

- States can cover “Katie Beckett” children through a state plan option or HCBS waiver; waiver coverage allows enrollment to be capped. ↩︎

- States electing the medically needy coverage option must cover certain groups of people, such as pregnant women and children, and also can choose to extend medically needy coverage to other groups, such as seniors and people with disabilities. ↩︎

- Additionally, as of 2016, six states are offering HCBS to people at risk of institutionalization through Section 1115 managed long-term care waivers. ↩︎

- Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Medicaid’s New ‘Health Home’ Option (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, January 2011), https://modern.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/medicaids-new-health-home-option/. ↩︎

- States can offer HCBS through their traditional Medicaid state plan benefit package or through a waiver; waivers allow enrollment to be capped. ↩︎

- Steve Eiken, Kate Sredl, Brian Burwell, and Paul Saucier, Medicaid Expenditures for Long Term Services and Supports (LTSS) in FY 2014, (Bethesda, MD: Truven Health Analytics, April 2016), https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/by-topics/long-term-services-and-supports/downloads/ltss-expenditures-2014.pdf. ↩︎

- Certain groups are exempt from mandatory enrollment in an alternative benefit plan and instead must have access to the traditional state plan benefit package. These include mandatory pregnant women, mandatory parents, and those who are medically frail (including individuals with disabilities or special medical needs, dual eligible beneficiaries, and people with long-term care needs). MaryBeth Musumeci, The Affordable Care Act’s Impact on Medicaid, Eligibility, Enrollment, and Benefits for People with Disabilities (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, April 2014), https://modern.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/the-affordable-care-acts-impact-on-medicaid-eligibility-enrollment-and-benefits-for-people-with-disabilities/. ↩︎

- 42 C.F.R. § 440.330. ↩︎

- Joan Alker, Sean Miskell, MaryBeth Musumeci, and Robin Rudowitz, Medicaid Premium Assistance Programs: What Information is Available About Benefit and Cost-Sharing Wrap-Around Coverage? (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, December 2015), https://modern.kff.org/report-section/medicaid-premium-assistance-programs-what-information-is-available-about-benefit-and-cost-sharing-wrap-around-coverage-introduction/ (citing United States Government Accountability Office, Medicaid and CHIP: Enrollment, Benefits, Expenditures, and Other Characteristics of State Premium Assistance Programs (Washington, DC: United States Government Accountability Office, Jan. 19, 2010), http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d10258r.pdf). ↩︎

- Iowa had waiver approval for and implemented a premium assistance program for some Medicaid expansion enrollees, but the program was discontinued by the state. ↩︎

- Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Deficit Reduction Act of 2005, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, February 2006), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/deficit-reduction-act-of-2005-implications-for/. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Institutional providers (hospitals) and nursing facilities: States are required to publish payment methodologies for public review and comment and payments are subject to upper payment limits for these providers based on what Medicare would have paid in aggregate. Physicians, other providers and managed care organizations: States are required to pay rates that are sufficient to ensure access equal to the rest of the area population. For MCOs, payment mush be actuarially sound. Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs): Under legislation enacted in 2001, states are required to pay these health centers and clinics based on a prospective payment system that relies on costs in a base year and trended forward. Prescription Drugs: Federal law requires that drug manufacturers enter into rebate agreements with HHS to provide their drugs through Medicaid. ↩︎

- Stephen Zuckerman, Laura Skopec, and Kristen McCormack, Reversing the Medicaid Fee Bump: How Much Could Medicaid Physician Fees for Primary Care Fall in 2015? (Washington, DC: Urban Institute, December 2014), http://www.urban.org/research/publication/reversing-medicaid-fee-bump-how-much-could-medicaid-physician-fees-primary-care-fall-2015. ↩︎

- Vernon K. Smith et al., Implementing Coverage and Payment Initiatives: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2016 and 2017 at 47 (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, October 2016) (citing 23 states using private health plans to deliver LTSS), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/report/implementing-coverage-and-payment-initiatives-results-from-a-50-state-medicaid-budget-survey-for-state-fiscal-years-2016-and-2017/. In addition, Vermont uses a state entity acting as a prepaid health plan to deliver MLTSS on an at-risk basis. ↩︎

- Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, The State Innovation Models (SIM) Program: A Look at Round 2 Grantees (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, September 2015), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/the-state-innovation-models-sim-program-a-look-at-round-2-grantees/. ↩︎

- Vernon K. Smith et al., Implementing Coverage and Payment Initiatives: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2016 and 2017 (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, October 2016), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/report/implementing-coverage-and-payment-initiatives-results-from-a-50-state-medicaid-budget-survey-for-state-fiscal-years-2016-and-2017/. ↩︎

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Medicaid & CHIP Strengthening Coverage, Improving Health (Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, January 2017), https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/program-information/downloads/accomplishments-report.pdf. ↩︎

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Medicaid & CHIP Strengthening Coverage, Improving Health (Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, January 2017), https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/program-information/downloads/accomplishments-report.pdf. ↩︎