Children’s Health Coverage: The Role of Medicaid and CHIP and Issues for the Future

The Role of Medicaid and CHIP for Children

Medicaid and CHIP are central sources of coverage for the nation’s children. Enacted in 1965 under Title XIX of the Social Security Act, Medicaid was created to provide health care coverage to blind and disabled individuals and families with dependent children receiving cash assistance. It has expanded over time, particularly for children. CHIP was created in 1997 to provide coverage to uninsured children in families with incomes above Medicaid eligibility levels. Under CHIP, states are permitted to use funds to create a separate CHIP program, expand their Medicaid program, or adopt a combination approach.1 CHIP helped spur efforts to expand eligibility to reach more low-income children, adopt strategies to simplify enrollment and renewal, and conduct outreach and enrollment efforts.

Medicaid’s size and scope is broader compared to CHIP. In 2014, Medicaid covered 36.1 million children and another 8.1 million children were covered through CHIP at some point during the year.2 Historically, children have accounted for about 21% of Medicaid spending for services; therefore, if the proportion of spending on children remained constant, an estimated $96 billion of the $458 billion in total Medicaid spending for services would be for children in 2014,3, 4 more than 7 times higher than CHIP expenditures of $13.5 billion in FY 2014.5

Both Medicaid and CHIP are federal matching programs; however, the CHIP match rate is higher than Medicaid and CHIP financing is capped. Under both programs, the federal government matches eligible state spending according to a formula that relies on states’ relative per capita income. The federal match rate for Medicaid ranges from 50% to 74% across states as of FY 2015.6 To encourage participation among the states when CHIP was enacted, the federal government provided enhanced (relative to Medicaid) matching payments for CHIP, which were further increased under the ACA. In FY 2015, prior to the ACA increase, the CHIP match rate ranged from 65% to 81% across states.7 Under Medicaid, federal matching funds are guaranteed with no pre-set limits. Tied to this financing guarantee, Medicaid provides an entitlement to coverage and states are prohibited from imposing enrollment caps or waiting lists. In contrast, federal funds under CHIP are capped nationwide and each state operates under an allotment. Under separate CHIP programs, beneficiaries are not entitled to coverage and at various times, states have imposed caps and waiting lists to control CHIP spending.

Both Medicaid and CHIP provide broad benefits and cost-sharing protections for low-income children. Children enrolled in Medicaid receive a comprehensive benefit package that includes the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit, long-term care, many rehabilitative services, and services provided at Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs). Under EPSDT, children are guaranteed comprehensive coverage including access to physical and mental health therapies, dental and vision care, personal care services and durable medical equipment. Given the limited incomes of enrollees, states generally are prohibited from imposing premium and cost-sharing for children enrolled in Medicaid with family incomes under 150% FPL. Compared to Medicaid, states have more flexibility around benefits and cost-sharing in separate CHIP programs. However, in both Medicaid and CHIP, total premium and cost-sharing expenses cannot exceed 5% of family income. As of 2016, 4 states had premiums or enrollment fees for children in Medicaid and 3 states charged cost sharing for Medicaid children, while 26 states required premiums or enrollment fees and 25 states charged co-payments for children in CHIP.8

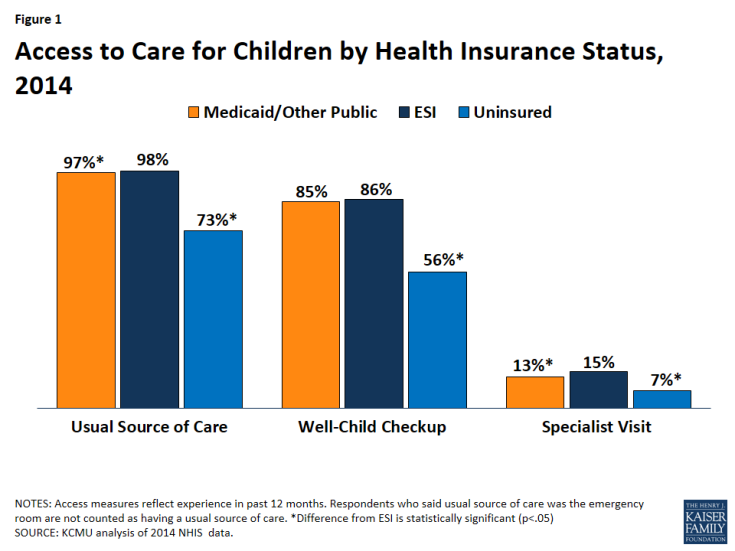

Children with Medicaid coverage have significantly better access to care than uninsured children, and their access is comparable to privately covered children (Figure 1).9 Children with Medicaid coverage are more like to have a usual source of care, well-child check-up and a specialist visit compared to uninsured children, and their access along these measures is similar to children with private insurance. Data also show children with Medicaid are less likely to delay or forgo care due to cost, to have gone more than two years without seeing a doctor, to have unmet dental need due to cost, and to have gone more than two years since visiting a dentist compared to uninsured children.10

Studies show that Medicaid and CHIP lead to improved health outcomes and other improvements for children and parents are satisfied with their child’s coverage. Some studies have found that Medicaid and CHIP coverage contribute to improved health outcomes, including reductions in avoidable hospitalizations and positive impacts on child mortality.11 Research also suggests that Medicaid and CHIP coverage contributes to improvements in school performance and long-term educational attainment, including increased college attendance.12 In addition, evidence shows that Medicaid and CHIP enrollment has a positive impact on future wages and reduces early adulthood mortality.13 Parents report that they are thankful for Medicaid and CHIP and have peace of mind knowing their children are covered.14 In particular, they appreciate the affordability of the coverage.15 Recent poll data show that when presented with a hypothetical situation of being uninsured and needing medical care, a large majority (88 percent) say that they would enroll an eligible child in Medicaid.16

Recent Legislation Related to Children’s Coverage

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) continued and bolstered efforts to cover children through Medicaid and CHIP. The ACA protects the gains achieved in children’s coverage by requiring states to maintain eligibility thresholds for children that are at least equal to those they had in place at the time the law was enacted through September 30, 2019. The ACA also established a minimum Medicaid eligibility level of 133% FPL for all children up to age 19. Prior to the ACA, the federal minimum for children ages 6 to 18 was 100% FPL; 21 states transitioned older children from CHIP to Medicaid in 2014 as a result of this change. In addition, the ACA required states to provide Medicaid to children aging out of their foster care system up to age 26. Moreover, the ACA enhanced enrollment in Medicaid and CHIP by establishing new streamlined processes, eliminating waiting periods in Medicaid, limiting waiting periods in CHIP, and increasing outreach and enrollment efforts. Lastly, the ACA increased the CHIP matching rate by 23 percentage points from 2016 through 2019, up to a maximum of 100%. In FY 2017, the CHIP match ranged from 88% to 100% with 12 states receiving 100% match.17

In April 2015, the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) extended funding for CHIP through September 30, 2017 without changing the basic structure of the program.18 This two year extension included authorization to implement the 23 percentage point increase to the enhanced federal match for CHIP. MACRA also provided increased funding for outreach and enrollment grants for states by $40 million in FY 2016 and FY 2017. In addition to funding, MACRA extended until September 2017 Express Lane Eligibility authority for states, which facilitates enrollment and renewal of eligible children.

Current Children’s Medicaid/CHIP Eligibility and Participation

As of January 2016, Medicaid and CHIP provide coverage to children with a median eligibility level at 255% FPL.19 Nineteen states, including DC, cover children in families with incomes at or above 300% FPL, while only three states limit eligibility to children in families with incomes less than 200% FPL (Figure 2).20 Arizona was the only state with enrollment closed in its separate CHIP program, which has been closed since 2010. However, enrollment in Arizona’s separate CHIP program is scheduled to reopen in late 2016. Even with the ACA’s Medicaid expansion to low-income adults, the median eligibility level for children (255% FPL) is much higher compared to that for parents (138% FPL), other adults (138% FPL), and pregnant women (205% FPL).21

Participation in Medicaid and CHIP is high with nine in ten (91%) children who are eligible enrolled in coverage.22 As of 2014, 32 states had over 90% of eligible children enrolled and the participation rate for eligible children was near or above 80% in all states. Reflecting ongoing outreach and enrollment efforts, the share of eligible children who are enrolled has increased over time, from 82% in 2008 to 91% in 2014. Between 2013 and 2014, there were larger increases in participation rates in states that adopted the ACA Medicaid expansion to low-income adults in 2014 compared to states that did not expand in 2014 (3.0 percentage points vs. 1.8 percentage points). The expansion to adults may have contributed to increased coverage among previously eligible children as a result of broad outreach and enrollment efforts associated with the expansion. Even with these high participation rates, there remain opportunities to further increase coverage by enrolling eligible children who remain uninsured.

Coverage for Children Today

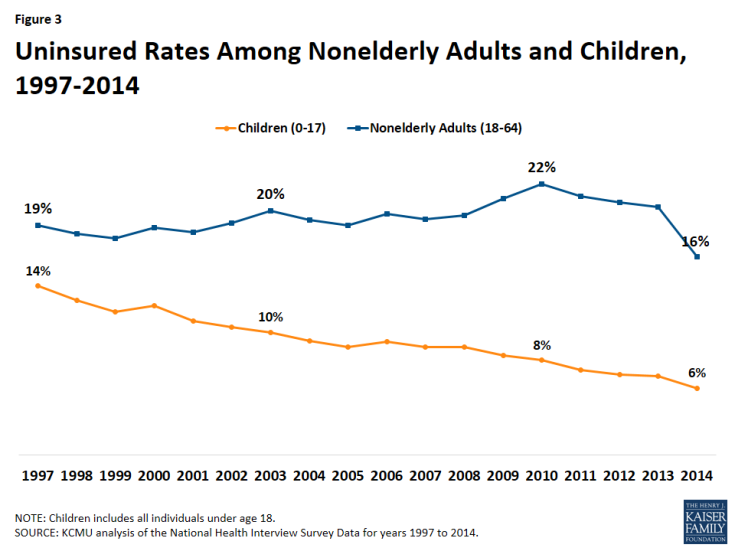

The children’s uninsured rate has fallen by more than half from 14% in 1997 to a historic low of 6% in 2014 (Figure 3).23 This decline reflects expansions in eligibility for Medicaid and CHIP over time, combined with efforts to streamline enrollment and renewal and outreach and enrollment campaigns. Children have had much larger gains in coverage than adults over time. Largely due to availability of public coverage through Medicaid and CHIP, children continued to gain coverage during the recent economic downturn when the uninsured rate for adults (for whom Medicaid eligibility is much more limited) climbed.

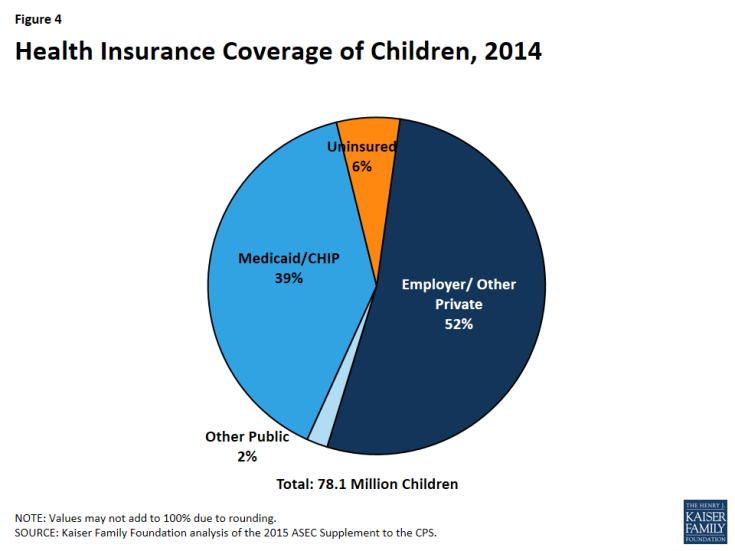

As of 2014, 94% of the over 78.1 million children in the United States had coverage, with nearly four in 10 covered by Medicaid and CHIP.24,25 Over half of children (52%) had private insurance, including an employer sponsored health plan, Marketplace insurance, or other non-group health coverage (Figure 4). Another nearly four in ten (39%) children were covered through Medicaid and CHIP.

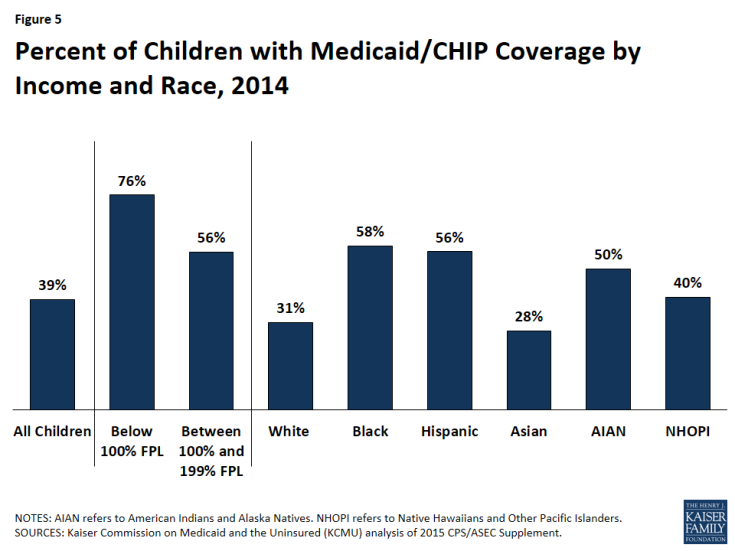

Medicaid and CHIP play a particularly important role in covering children in low-income families and children of color.26 More than three-quarters (76%) of children in families with incomes below the poverty level are enrolled in Medicaid and CHIP, and over half (56%) of children in families with incomes between 100% and 199% FPL are enrolled in Medicaid and CHIP.27 The programs also play a substantial role for children of color, covering more than half of all Black, Hispanic, and American Indian and Alaska Native children (Figure 5).28

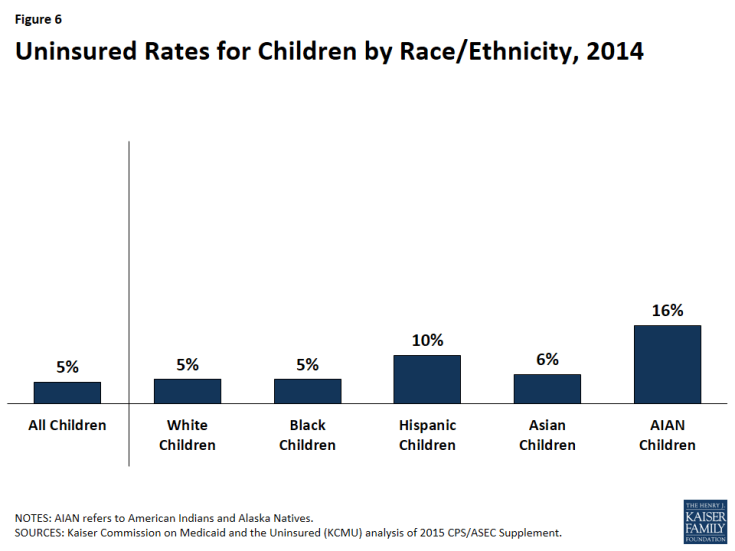

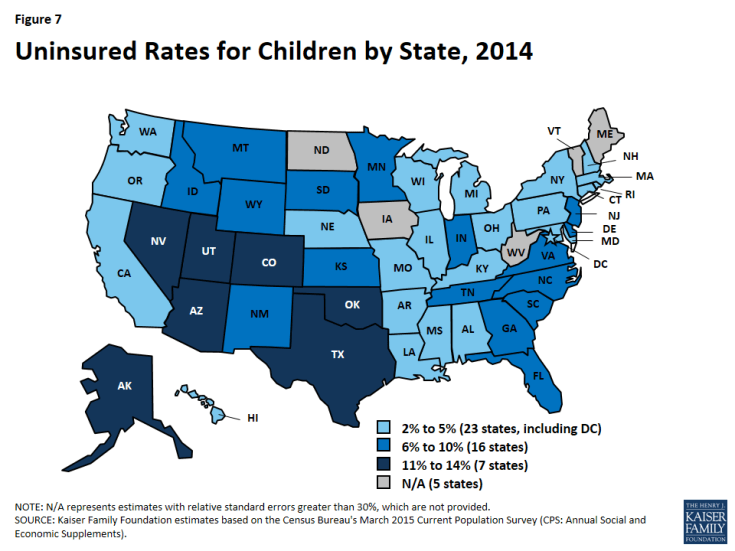

An estimated 5 million children remain uninsured as of 2015, and a child’s risk of being uninsured varies based on his or her race and ethnicity and where he or she lives. Hispanic and American Indian and Alaska Native children are at least twice as likely to be uninsured compared to White children (Figure 6). Hispanic families face a range of barriers to enrollment in coverage, including complex eligibility rules for immigrants, language barriers, and concerns about negative impacts on immigration status from enrolling in health coverage.29,30 American Indian and Alaska Native families also face specific barriers to enrollment including mistrust of federal and state governments, certain cultural beliefs, and a preference for relying on Indian Health Services (IHS) services for care or the belief that the federal government should fund all needed care through IHS.31 Across states, children’s uninsured rates range from at or less than 5% in 23 states, including DC, to at or above 11% in 7 states (Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, Oklahoma, Texas, and Utah) (Figure 7). Almost half (49%) of all uninsured children live in just seven states (Arizona, California, Florida, Georgia, New York, North Carolina, and Texas).32

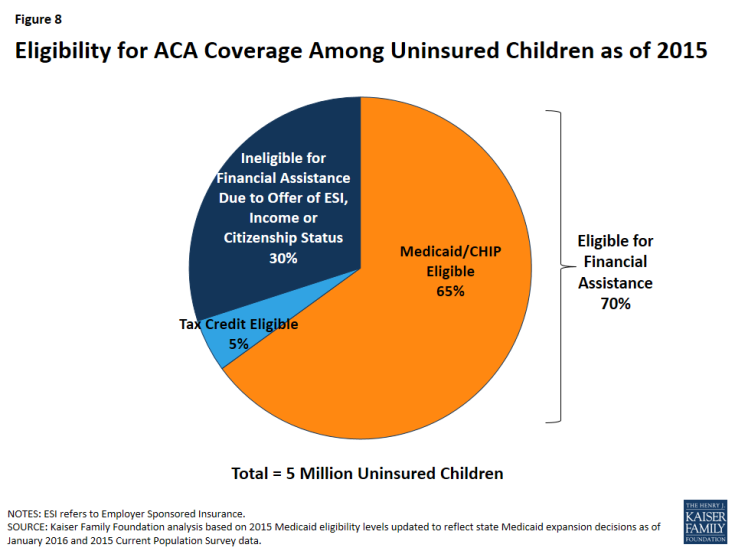

Nearly two in three (65%) uninsured children are eligible for Medicaid or CHIP (Figure 8).33 An additional 5% of uninsured children are eligible for assistance to purchase health insurance through Marketplaces. The remaining 30% of uninsured children are ineligible for financial assistance due to income or an offer of employer sponsored insurance in the family, or because they do not qualify for coverage based on immigration status. Undocumented children are not eligible for public coverage. In addition, lawfully residing immigrant children in the country for less than five years are not eligible for Medicaid or CHIP unless a state has taken option to waive this five year waiting period. As of January 2016, 29 states had taken up this option in Medicaid or CHIP.34 Since then, Florida and Utah also adopted this option.

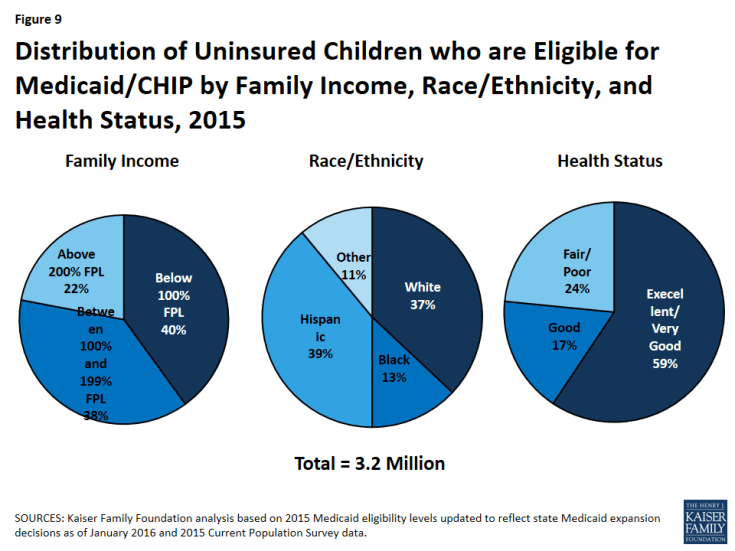

The majority of the 3.2 million children that remain uninsured but are eligible for Medicaid or CHIP are in low-income families and are children of color, and roughly one in four is in fair or poor health (Figure 9). While the vast majority of uninsured but eligible children have a full or part-time worker in the family (83%), 78% live in low-income families.35 Nearly two-thirds (63%) of the remaining uninsured children who are eligible for Medicaid or CHIP are children of color, including more than one in three (39%) who are Hispanic. Almost a quarter (24%) of children who remain uninsured but eligible for Medicaid or CHIP are in fair or poor health.36 Uninsured children eligible for Medicaid or CHIP are almost evenly split between states adopting the ACA’s Medicaid expansion for low-income adults (53%) and not currently adopting the expansion (47%).37 More than one in three (37%) uninsured but eligible children live in just four states (California, Florida, New York, and Texas).38

Figure 9: Distribution of Uninsured Children who are Eligible for Medicaid/CHIP by Family Income, Race/Ethnicity, and Health Status, 2015

Issues for the Future

Sustaining Children’s Coverage Gains

The outcome of the next CHIP reauthorization debate will have implications for sustaining children’s coverage gains. As stated above, MACRA extended CHIP funding through September 2017. Without additional CHIP funding, children in Medicaid expansion CHIP programs would retain Medicaid coverage since the ACA maintenance of eligibility provisions for children in Medicaid and CHIP are in place through FY 2019. Other children could move to coverage through the Marketplace and others may become uninsured. There are a number of options on the table including extending CHIP, expanding Medicaid, permitting CHIP-financed Marketplace subsidies, enhancing Marketplace coverage, or broadening state innovation waivers.

The debate around CHIP reauthorization is likely to focus more broadly on key issues for children’s coverage, including benefits and out of pocket costs. One option that may be considered would be to transition children from CHIP to Marketplace coverage. While Marketplace coverage may generally be comparable to CHIP, Marketplace coverage may lack dental, vision, and habilitative services, in addition to other services specific for children with special health needs.39 In addition, analyses show Marketplace coverage costs can greatly exceed the 5% of household income allowable under Medicaid or CHIP.40, 41 Affordability of coverage is a primary concern for parents.42 Moreover, under current rules, some children are not eligible for tax credits in the Marketplace because a parent may have access to “affordable” employer coverage; however, the affordability test for employer coverage is based on a calculation of the individual coverage relative to a workers wages (not the cost of a family policy). This situation is referred to as the “family glitch” and leaves children uninsured.

Continuation of federal financing to support children’s coverage is a key for maintaining coverage gains. The availability of federal financing has been instrumental in attaining high levels of coverage for children. Extending CHIP or financing children’s coverage through new or alternative mechanisms will be key to sustaining coverage gains to date. More broadly, debate about funding for children’s coverage could arise at the same time Congress may consider options to reform Medicaid financing and reduce federal spending. Since Medicaid has been the primary program for children’s coverage, proposed changes to Medicaid may have bigger implications for sustaining children’s coverage.

Continuing to Advance Children’s Coverage

Targeting outreach and enrollment efforts to hard-to-reach populations may help reduce remaining disparities in children’s coverage. As indicated above, some groups of children, including Hispanic and American Indian and Alaska Native children, remain at higher risk of being uninsured. Developing targeted outreach and enrollment efforts to overcome these barriers will be key for reducing ongoing disparities in coverage for these children. Moreover, it is important for efforts to continue over the course of the year, since enrollment in Medicaid and CHIP is not limited to the open enrollment period of the Marketplaces. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has provided several rounds of grant funding to support outreach activities to reach eligible but uninsured children. One June 13, 2016, CMS announced it will provide $32 million to community organizations to support efforts to reach out to families with children eligible for Medicaid and CHIP through its current grant cycle.43

States have the opportunity to reach more uninsured children by adopting policy options that expand children’s eligibility for Medicaid and CHIP and facilitate enrollment and renewal. For example, additional states could take up the option to eliminate the five year waiting period for lawfully present immigrant children in Medicaid or CHIP. States also can expand coverage for former foster youth from other states. While the ACA requires all states to provide Medicaid coverage to youth who were in foster care in the state up to age 26, it is a state option to extend coverage to former foster youth from other states.44 As of January 2016, 13 states had taken up this option. States also can expand CHIP coverage to dependents of state employees, which 15 of the 36 states with separate CHIP programs had done as of January 2016.45 States have several options available to facilitate enrollment and renewal of eligible children. For example, as of January 2016, 18 states were providing presumptive eligibility for children in Medicaid or CHIP, 10 states were using Express Lane Eligibility to enroll or renew children in Medicaid or CHIP based on findings from other programs, 5 states were using SNAP data to facilitate enrollment or renewal of children, and 32 states were providing 12-month continuous eligibility to children.46 In June 2016, CMS provided an information bulletin that highlights the existing tools available to states to support enrollment and retention of eligible children and resources available to states to support implementation of these options.47

Conclusion

In sum, Medicaid and CHIP are a central source of coverage for low-income children. The broad benefits and financial protections afforded under Medicaid and CHIP enable children’s access to health care services that lead to improvements in health outcomes and other areas of their lives. Reflecting continued coverage gains over time, Medicaid and CHIP cover nearly one in four children today, and children’s uninsured rate has fallen to a record low. However, despite these gains, an estimated five million children remained uninsured as of the beginning of 2015 and disparities in coverage continue based on a child’s race/ethnicity and where a child lives. Nearly two-thirds of remaining uninsured children are eligible for Medicaid and CHIP, suggesting that continued coverage gains can be achieved through targeted outreach and enrollment efforts. States also can enhance children’s access to coverage by adopting options that expand children’s eligibility for Medicaid and CHIP and that facilitate enrollment and renewal in the programs. Looking ahead, the future of CHIP will have important implications for children’s coverage after 2017. As policy options are considered it will be important to consider how they affect the benefits and cost sharing of coverage options for children.