Beyond the Numbers: Access to Reproductive Health Care for Low-Income Women in Five Communities

KFF: Usha Ranji, Michelle Long, and Alina Salganicoff

Health Management Associates: Sharon Silow-Carroll, Carrie Rosenzweig, Diana Rodin, and Rebecca Kellenberg

Introduction

In Washington, DC, and in state capitols across the nation, policy debates over the future of access to reproductive and sexual health services are shaping the range of services and providers available to low-income women. Access to these services, including contraceptive care, sexually transmitted infection (STI) prevention and treatment, obstetrical care, and abortion services, have a profound impact on women’s lives. While instructive, national statistics can mask wide regional and local variation, as well as disparities across socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic groups. In order to understand what is happening at the local level, we went beyond the statistics to see how these policies are playing out in diverse communities across the United States.

Service availability and policies related to health care, contraception, and abortion vary significantly across and within states. State policymakers determine whether to expand Medicaid coverage to low-income adults under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), establish and fund family planning programs for uninsured residents, and adopt rules that regulate abortion services. These state policies also intersect with local factors; the number and distribution of family planning and safety net providers, the content of school-based sex education, cultural traditions of local populations, and underlying social determinants of health all shape access to reproductive health care at the community level.

Shifting federal policies and priorities add to already complex state and local dynamics. New federal rules related to the Title X family planning program, for example, directly affect which organizations can receive funding to provide family planning services to low-income and uninsured women, and indirectly affect the availability of other basic health services.

Recognizing the large disparities in access to health care across the country and the importance of the local safety net for low-income populations, KFF, working with Health Management Associates (HMA), undertook a study to identify distinct challenges that low-income women face in obtaining reproductive health care in diverse communities. The research team examined access in five communities across the United States that represent urban and rural areas, regions that are federally designated as medically underserved and health professional shortage areas, and areas that have faced closure and consolidation of family planning providers and hospitals. These communities also vary in demographic characteristics, and have populations that face health inequities such as low-income women, African Americans, Native Americans, immigrants, and refugees. The study team went to: Dallas County (Selma), Alabama; Tulare County, California; St. Louis, Missouri; Crow Tribal Reservation, Montana; and Erie County, Pennsylvania. Between February and September 2019, staff from KFF and HMA conducted structured interviews with local safety net clinicians and clinic directors, social service and community-based organizations, researchers, and health care advocates (“interviewees”) that work on a range of reproductive and sexual health issues in each of the communities. Additionally, at each site we convened a focus group with low-income, reproductive age women to understand their perspectives on the care they receive and the challenges they face. Through this combination of interviews and focus groups, we learned about the experiences of women living in these communities and the reproductive health professionals caring for them.

This report summarizes the major findings, highlighting cross-cutting themes and the degree to which low-income women in diverse communities face challenges in accessing reproductive and sexual health care. We also report on promising initiatives established by community providers to address barriers and improve access to these basic services. In-depth case studies of each community are available at https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/report/beyond-the-numbers-access-to-reproductive-health-care-for-low-income-women-in-five-communities.

Key Findings

Despite their differences, low-income women in these communities faced many similar challenges in accessing health care. While each community had distinct environments and features, the barriers to reproductive health services and factors contributing to those barriers were largely consistent, suggesting that these challenges and themes are prevalent well beyond the five communities studied. The key findings are categorized into five areas:

- Cultural and Social Determinants of Health: In each of the communities, poverty, cultural factors, and social determinants were identified as having a considerable impact on women’s ability to prioritize, afford, and get to family planning or abortion services. In addition, the residual effects of historical abuses by the medical establishment result in persistent mistrust of providers in some communities. This was most prominent among the Crow tribe and residents of Dallas County, AL; both communities still feel the legacy of a history of injustices such as forced sterilization upon many Native American women and the Tuskegee syphilis study in a neighboring community in Alabama.

- Coverage: Interviewees identified lack of coverage options for basic health care services for low-income women as a prominent challenge in states that did not adopt the ACA’s Medicaid expansion. Interviewees also identified ways to strengthen Medicaid to improve services available to enrollees, such as eliminating pre-authorization for certain contraceptive methods, increasing provider participation in the program, and improving systems to connect uninsured women to Medicaid-funded family planning programs.

- Provider Supply and Distribution: There are provider shortages in many communities, especially in expansive, rural areas. Interviewees said that challenges with recruitment and retention of clinical staff create access barriers for women. Many interviewees identified gaps in the availability of female clinicians, language translation services, and the need for culturally-congruent care.

- Sex Education: All five communities emphasized the need for comprehensive sex and STI education. A lack of information was said to leave many girls and women uninformed or misinformed about their reproductive health care, contraceptive options, and how to access services.

- Abortion Environment: Abortion was difficult to access in all of the communities. Stigma, anti-abortion beliefs, and policy restrictions at the state and/or community level shape the accessibility of abortion services. Policy restrictions, such as those in Missouri, Alabama, and Pennsylvania, that mandate counseling and waiting periods and bar insurance coverage for abortions dissuade providers from offering services and raise costs for women. Anti-abortion beliefs and stigma were also raised as barriers in Montana and California, states that don’t impose these types of abortion restrictions.

The discussion below highlights perspectives and lessons learned from health care providers, leaders of local support agencies, and low-income women about key barriers as well as how to improve access to reproductive health services.

Cultural and Social Determinants of Health

Despite the differences in the racial and ethnic composition of the populations, local histories, and state-level policies, this theme was prominent and overarching in all five communities. Increasingly, policymakers, advocates, payors, and providers are acknowledging the impact of social determinants such as housing instability, food insecurity, limited education and job training, crime and violence, and unmet transportation needs on health care access and outcomes. For example, a growing number of states are requiring Medicaid health plans to address social determinants of health as part of contractual agreements. Still, unmet needs related to poverty continue to create significant barriers to reproductive care. The increase in anti-immigrant sentiment and ICE raids, as well as long-standing discriminatory practices and negative historical experiences with the health care system, not only affect access to reproductive health services but also utilization and quality of health and social services.

Poverty, a shortage of affordable housing, and lack of education and employment opportunities leave many women struggling to meet basic needs and with few resources to seek reproductive health services. Interviewees in all regions reported that socioeconomic stresses often result in women prioritizing food and shelter above preventive health care and family planning. One interviewee noted that multi-generational poverty locks women in situations that prevent them from making their own choices. Anxiety and depression are common among low-income women, yet all five communities faced gaps in behavioral health care and related support services.

Immigration status affects women’s willingness and ability to seek family planning, health, and social services. Immigrants who are undocumented or who are not proficient in English face heightened challenges in seeking services due to language barriers, fear of deportation, or concerns about jeopardizing their immigration proceedings due to changes in the public charge rule. Interviewees in Tulare and Erie Counties, both communities with sizable immigrant populations, reported that racism and fear of ICE have increased in recent years. In Tulare County, interviewees noted there have been ICE raids on domestic violence shelters across California and said that women who call to report abuse may not seek services for fear of deportation. Several focus group participants recounted experiences delaying or going without health or pregnancy-related care when they were undocumented.

“If you ask for public assistance while your documents are being processed, they are not going to give you your legal status. That’s why many people don’t want to get [assistance]. Because you are in the process, and they are going to see and think ‘these people are going to be a public burden.”

–Focus group participant, Tulare County, CA

Trauma, prior negative experiences with the health care system, and lack of cultural competency among providers discourage women from accessing reproductive care. Some focus group participants reported that health care providers pressured them to use contraception or to choose certain methods. Others reported providers dissuading them from using particular types of contraception – sometimes based on outdated research and practices or personal attitudes about ideal family size or the age of the patient. In each community, different cultural and historical factors interacted with access to reproductive health care:

- Refugee communities – In Erie, Pennsylvania, interviewees explained that reproductive health and family planning preferences vary widely among the large refugee community, reflecting diverse religious and cultural beliefs. While many refugees face language barriers when seeking care, case managers, dedicated service agencies, and a Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) focus on providing culturally appropriate care to support women’s access to their preferred methods of family planning.

- African Americans in the rural south – In Selma, Alabama, some interviewees reported that the legacy of slavery and the Jim Crow era, historical mistrust of the medical establishment (exacerbated by the Tuskegee syphilis study in nearby Macon county), and an insufficient number of female clinicians of color contribute to lack of engagement in early and preventive care. Focus group participants and interviewees also noted the influence of conservative religious beliefs among many in the community, particularly with regard to sex outside of marriage and abortion.

- Crow tribe – Crow interviewees in Montana described traditional beliefs that emphasize modesty, discourage the discussion of sexuality-related topics, and hold that babies are always a blessing. These beliefs, along with historical negative experiences with the federal and state health care systems, such as the coerced sterilization of indigenous women in the 1960s and 1970s, affect utilization of family planning services among Crow women and teens.

“Let’s put [family planning services] in places where we know the people who need access to it are, instead of making them come to us.”

–Katie Plax, Medical Director, the SPOT, St. Louis, MO

Domestic violence interacts with sexual health. Several interviewees reported that women in abusive relationships often experience reproductive coercion in which their partners prevent them from using contraception or sabotage their chosen method. As a result, women are not able to make their own reproductive decisions, and some have had multiple children they did not intend to have.

| Community Perspectives on Addressing Barriers Arising from Social Determinants of Health |

Interviewees and focus group participants described goals for the health care system, strategies they were implementing, and lessons they have learned to address some of the barriers to sexual and reproductive health service in their communities. These include:

|

Availability of Coverage

Thirty-six states plus DC have expanded Medicaid coverage to low-income adults without dependent children under the Affordable Care Act. In states that have not expanded their Medicaid programs, these adults generally do not qualify for full-scope Medicaid coverage.1 While Medicaid income eligibility levels for pregnant women in all states are higher than for people who are not pregnant, pregnancy-related coverage typically ends at 60 days postpartum. Two of the five communities in this study, St. Louis, Missouri, and Dallas County, Alabama, are in states that have not expanded Medicaid. As a result, they have lower rates of Medicaid coverage than the other three communities, which are located in expansion states.

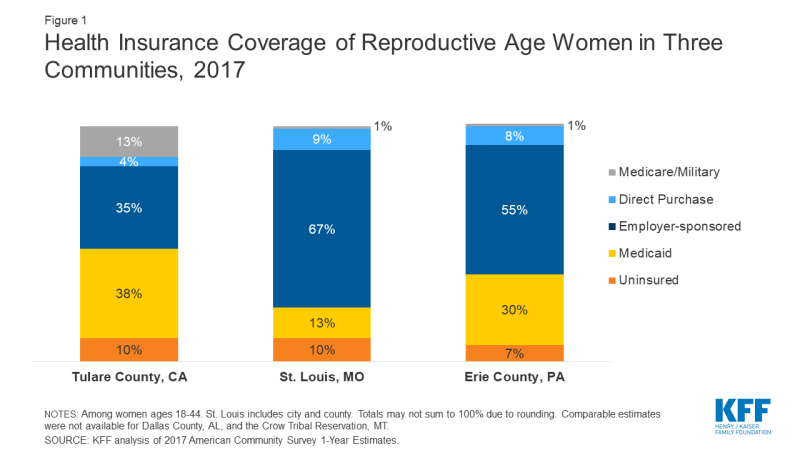

Figure 1 shows the insurance coverage profile of reproductive age women in Tulare County, the St. Louis region, and Erie County. Comparable estimates were not available for Dallas County and the Crow tribal reservation. All of the communities that were studied are in states with a Medicaid-funded family planning program that provides contraception to uninsured, low-income women, except Missouri, which offers an entirely state-funded program.2

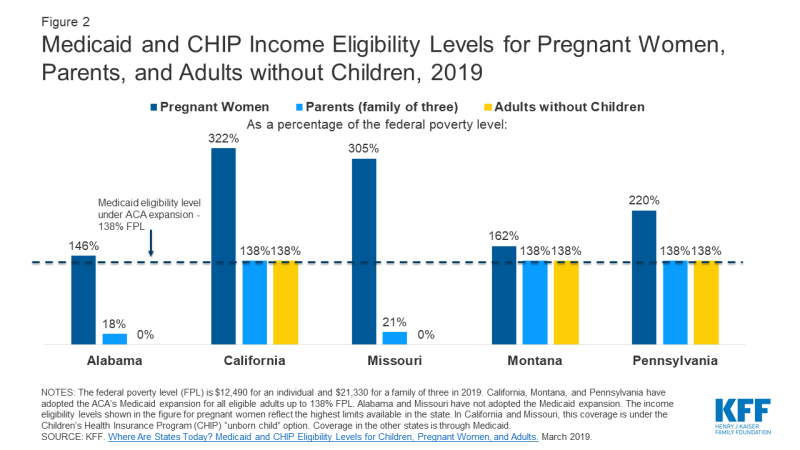

Women in states that did not expand Medicaid have limited options for obtaining coverage for basic health care services. Interviewees in St. Louis, Missouri, and Dallas County, Alabama, both in non-expansion states, reported that most low-income women have no coverage for preventive, acute, or chronic care outside of pregnancy (Figure 2). Annual income eligibility for parents in a family of three is capped at $3,839 (18% FPL) in Alabama and $4,479 (21% FPL) in Missouri. Parents with incomes above these limits do not qualify for coverage. Adults without children in these states do not qualify for Medicaid regardless of income, unless they have a disability or are over age 65. Additionally, federally subsidized coverage through the ACA’s Health Insurance Marketplace is only available to those with incomes above the federal poverty level. This means many of these individuals are not eligible for financial assistance to purchase coverage on their own, creating a coverage gap. Many focus group participants in Dallas County reported that when they need health care, they go to the emergency room, where they are not required to pay fees upfront and would not be turned away. While many knew about the FQHC in their community, they noted that even a sliding fee schedule was too costly for them.

“The lack of expansion of Medicaid is the single greatest factor [affecting access to family planning services] beyond a shadow of a doubt.”

–Felecia Lucky, President, Black Belt Community Foundation, Selma, AL

Figure 2: Medicaid and CHIP Income Eligibility Levels for Pregnant Women, Parents, and Adults without Children, 2019

Loss of Medicaid eligibility after childbirth for women who live in non-expansion states and the lack of automatic transitions to state family planning programs result in gaps in reproductive health care for low-income women with infants. Both interviewees and focus group participants reported that losing full Medicaid coverage at 60 days postpartum, or due to small changes in income, disrupts continuity of care and creates barriers to family planning and other health care services. Also, providers in Missouri said that the state’s policy that disqualifies clinics that provide or are affiliated with abortion providers from participating in Medicaid has reduced women’s access to family planning, as well as to abortion services.

Focus group participants and providers reported experiencing challenges with certain Medicaid rules and low reimbursement rates. There was clear consensus that Medicaid coverage is important for facilitating access to family planning services; yet some clinicians and focus group participants raised concerns with various Medicaid policies. For example, in St. Louis, providers said that state Medicaid rules tie coverage for long-acting revisable contraceptive (LARC) devices (IUDs and contraceptive implants) to specific patients; if a patient does not show for her appointment, the device cannot be used for another woman and may go unused, thus discouraging providers from stocking supplies and providing same-day access. The state has reportedly eliminated this requirement, but one provider noted that there were not yet any guidelines from the state to define or help facilitate the process. Across study states, providers also discussed low reimbursement rates as problematic, and women discussed their frustrations with having a limited range of providers who participate in the program.

| Community Perspectives on Addressing Coverage Barriers |

|

Provider Supply and Distribution

All five communities studied are “medically underserved,” and are health professional shortage areas, designated by HRSA as having too few primary care providers, high infant mortality, high poverty, or a large elderly population. In recent years, many rural areas have experienced a spike in hospital closures or a reduction in obstetrical services, particularly in states that have not expanded Medicaid. This has forced women to travel long distances to see medical providers, particularly for maternity care. In addition, the emergence of federal and state restrictions on funding for reproductive health services is starting to limit the supply of providers that receive funding to serve low-income and uninsured women. The Title X national grant program funds local clinics to provide free or low-cost family planning services to uninsured and low-income individuals. In 2019, the Trump administration finalized new regulations that prohibit any sites that receive Title X funding from providing abortion referrals. They also mandate referrals to prenatal services for all pregnant patients, and require complete financial and physical separation from sites that provide abortion services. These rules were not in effect at the time of the visits to these communities, but some family planning providers that were interviewed raised concerns that such policies would result in a considerable reduction in the share of providers participating in Title X and jeopardize their ability to continue providing family planning services to low-income and uninsured women.

While most focus group participants reported that they know where to go for family planning services, some faced obstacles to obtaining their preferred method in a timely fashion, and others were misinformed about their contraceptive options. In Missouri, pre-authorization and limitations on reimbursement for LARC preclude women from obtaining these methods on the day of their initial visit. This was raised as especially challenging for low-income women who have to take time off work, arrange for childcare, or travel long distances to a clinic. Some focus group participants shared misgivings and concerns about the side effects and safety of LARC methods based on prior personal or friends’ experiences. Interviewees in multiple regions noted a lack of training in LARC insertions and removals among community providers. In Selma, the county health department was in the process of training a clinician to insert IUDs, but at the time of the site visit, women had to go to another county health department or private provider participating in the state’s family planning program if they wanted to get an IUD inserted. Plan B, emergency contraception that helps prevent pregnancy when taken within 72 hours of unprotected sex, was generally available in most communities. However, interviewees and focus group participants cited cost as a barrier to obtaining it over the counter, and some women confused it with medication abortion. Costs associated with family planning in general were often a barrier for women who are uninsured, undocumented, and recent immigrants. In Dallas County, Alabama, fragmentation of the health care system meant that low-income women must go to different clinics for contraception, primary care, and obstetrical care, though a rural health center is in the process of implementing a more integrated approach to serve women in the community.

Rural areas, in particular, face severe provider shortages and persistent challenges in recruiting and retaining clinicians trained to offer reproductive and sexual health services. Focus group participants and interviewees described shortages of family planning providers in the rural and low-income areas. They also reported insufficient numbers of providers offering STI testing and treatment, HIV care, obstetrical care, trans-competent and LGBTQ-friendly services, and a scarcity of abortion providers. Practice consolidation in Erie County has resulted in limited choices of obstetricians for those enrolled in Medicaid. At the time of the site visit, the IHS facility on the Crow reservation did not have an ultrasound technician, but they have since hired someone for this position. Interviewees in Alabama reported that the state’s restrictive Medicaid eligibility limit and low reimbursement rates have contributed to a series of hospital closures in the region. This has left the Selma-based hospital with the only maternity ward and obstetrics clinic in the seven-county region. Interviewees in Selma, Tulare County, and the Crow reservation cited challenges attracting physicians to rural, low-income regions, and retaining them after they complete medical school loan forgiveness programs. Telemedicine was identified by many interviewees as an emerging solution to address barriers in these areas, but upfront costs can hinder these efforts, and not all communities have access to broadband. At the time of this study, none of the communities offered reproductive health services using telemedicine beyond e-prescriptions.

“If they have a bad experience with one doctor, they don’t want to go to that practice again, even to another doctor. And there is nowhere else close by, or they don’t accept Medicaid.”

–Provider, Erie, PA

Long travel distances and lack of public transportation in rural regions are major barriers to reproductive services, but transportation issues arose in urban communities as well. Women in some communities face logistical obstacles to obtaining services in a timely manner. This is particularly apparent in an area like Dallas County, Alabama, where many obstetrical care providers have closed, and there is no meaningful public transit infrastructure. Some focus group participants in Selma described having to pay friends or family to drive them to a clinic. Transportation was also problematic for women in the Crow tribe who must travel off the reservation to Billings, Montana, for prenatal services after 30 weeks of pregnancy. The sheer size of Tulare County also makes transportation difficult for low-income farmworkers who often do not have a car and must travel long distances for their care. Even in St. Louis, an urban community, women who lived in the county reported difficulty getting to care as public transit options fell short for them.

|

Community Perspectives on Addressing Provider Supply

|

|

Sex Education

In all of the communities, insufficient sex education for youth emerged as a key issue. Today, about half of states (24 plus DC) require schools to provide sex education, and 34 plus DC require HIV education. A minority of states (18 plus DC), however, require sex education to include information on contraception, while 26 states require that programs stress abstinence. The Trump administration has increased investment in abstinence curricula, and state governments have awarded grants to crisis pregnancy centers (CPCs), faith-based organizations that counsel women against abortion, to teach abstinence. Furthermore, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently reported a rise in rates of many STIs, particularly among teens and young adults. In the case study interviews and focus groups, many individuals raised concerns about limited sex education and its contribution to poor health literacy about sexual and reproductive health.

Interviewees described variation in sex education across schools and felt that the content did not cover much of the information young people need; most areas stressed abstinence or “abstinence plus”3 curricula. Sex education curricula are typically selected at the local school district, school, or classroom level, which can cause wide variation in content even within the same community. Focus group participants perceived the availability and curricula of sex education as inconsistent among schools and often inadequate for high school-aged students. The Erie City School District adopted the evidence-based, comprehensive FLASH curriculum,4 while CPCs teach “character education” promoting abstinence in many Erie County schools. An interviewee reported that the CPCs receive state, federal, and private funding, enabling them to conduct more outreach and programs than the more comprehensive reproductive health care providers. An interviewee in St. Louis County recounted recent parent and teacher pushback to the limited sex education from faith-based groups, resulting in the adoption of comprehensive sex education curricula in several school districts. Interviewees in all of the communities concluded that lack of comprehensive sex education in schools contributes to high rates of STIs, HIV, and teen pregnancy. This sentiment was also expressed by many focus group participants who felt that young people were not getting the information they needed to avoid unintended pregnancy and prevent the transmission of STIs.

“Most sex education is informal and focused more on girls than boys. They’re taught to behave with modesty and ‘keep themselves out of trouble’.”

–Lucille Other Medicine, Program Assist., Messengers for Health, Crow reservation, MT

Focus group participants and interviewees indicated that cultural influences and norms limit knowledge about contraception and STIs. In Dallas County, interviewees and focus group participants noted that most churches discourage discussion of sexual health, though a few have hosted events to promote HIV prevention and family planning. Some interviewees felt that formalized, comprehensive sex education in schools could be particularly important in more conservative communities, such as Tulare County, where discussions about sexual and reproductive health may not be commonplace at home. Providers on the Crow reservation also pointed out that discussions in the family about sexuality and reproductive health are not part of the cultural norm, and many young people lack access to basic health information.

Abortion Restrictions

Federal and state regulations shape access to abortion, and this was evident in all of the communities included in this study (Table 1). The federal Hyde Amendment restricts state Medicaid programs from using federal funds to cover abortions beyond the cases of life endangerment, rape, or incest. However, 16 states use their own state funds to cover abortions in other circumstances. Many other states have imposed restrictions on abortions including waiting periods, abortion facility requirements, and gestational age limits, some with the intent to overturn Roe v. Wade. These restrictions have translated to clinic closures in several states and the total absence of abortion clinics in many communities. This makes abortion effectively inaccessible for some women, particularly those who are poor or who live long distances from the nearest abortion provider.

Access to abortion in the five communities is severely limited, due to restrictive state policies resulting in a shortage of abortion providers and/or long travel times, plus a lack of transportation options. Alabama and Missouri have enacted some of the strictest abortion regulations in the nation, contributing to closures that leave just one abortion provider in Missouri (located in St. Louis), and one abortion provider in Montgomery, Alabama, that serves all of southern Alabama, parts of Mississippi and the Florida panhandle. Recent laws passed in these states would have essentially outlawed abortions if they had not been (temporarily) blocked by the courts.5 Yet, outside of Missouri’s attempt to ban abortion legislatively, the clinic in St. Louis remains vulnerable to closure. It is at the center of a state-level investigation about facility licensing that has generated national attention. A decision is expected in early 2020 as to whether the clinic can remain open.

| Table 1: Policies Limiting Abortion Access in Alabama, California, Missouri, Montana, and Pennsylvania | |||||

| Alabama | California | Missouri | Montana | Pennsylvania | |

| Waiting period required after mandated counseling | 48 hours | 72 hours | 24 hours | ||

| Gestational age limit | 20 weeks | Viability | Viability | Viability | 24 weeks |

| Abortion can only be performed by licensed physician | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Parental consent required for minor to obtain abortion | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Abortion coverage prohibited in ACA Marketplace plans | √ | √ | √ | ||

| State payments for abortion prohibited* | √ | √ | √ | ||

| NOTES: *Coverage limited to cases of rape, incest, life endangerment of woman. SOURCES: Guttmacher Institute. State Laws and Policies, An Overview of Abortion Laws. As of October 1, 2019. KFF, Intersection of State Abortion Policy and Clinical Practice, June 2019. |

|||||

Three of the counties studied (Erie, Tulare, and Dallas) have no abortion providers. Even in Tulare County and the Crow reservation, which are in states that cover abortion services under their Medicaid program and have very few restrictions on the provision of abortion, women must travel at least an hour to reach the nearest provider. Crow women must travel to Billings because the Indian Health Service, as a federal agency, is prohibited from providing abortion.

In each of the communities studied, anti-abortion sentiment played a significant role in limiting access to abortion services. Interviewees reported intense protesting outside abortion clinics in Montgomery and St. Louis and noted that protestors contributed to the closing of clinics in Erie and Selma. In Tulare County, California, anti-abortion billboards lined the highway and the Planned Parenthood of Visalia in Tulare County had been vandalized numerous times despite not providing any abortion services onsite. Focus group participants shared that protestors and cultural stigma surrounding the procedure made them feel ashamed or afraid, or deterred them from discussing or seeking an abortion. Interviewees in Dallas County and St. Louis reported that some providers and health center staff discourage abortions. Some focus group participants in St. Louis felt the state-mandated counseling was intended to make them second guess their own decisions. In many of these communities, churches play a prominent role in daily life, and religious influences discourage women from seeking abortions. In Selma, Tulare, and the Crow reservation, many focus group participants expressed opposition to abortion and said they would not consider it an option for themselves. In every focus group, however, there were a few women who said they had had an abortion or knew of someone who had one.

There was misinformation or lack of information about where women could obtain an abortion, and in some communities, focus group participants believed abortion was illegal in their state. In the communities with strict anti-abortion laws and strong anti-abortion environments, some interviewees and focus group participants incorrectly believed that abortion is illegal in their states. One crisis pregnancy center (CPC) in Erie had a large presence and offered a range of services such as pregnancy tests, STI screening, ultrasounds, and referrals to prenatal care, all at no cost to clients. Many interviewees referred women to the site because they mistakenly thought the CPC offered contraception and abortion referrals. More than one interviewee in Selma mistakenly thought that a local CPC offered abortions, and one listed them on their patient referral sheet for “abortion services,” just above the abortion providers in Montgomery and Tuscaloosa.

Limitations on Medicaid coverage for abortion services in some states, as well as procedure costs, make abortion unaffordable for many low-income women. The California and Montana Medicaid programs cover abortion services beyond the Hyde Amendment exclusions for life endangerment of the woman, rape, and incest. Alabama, Pennsylvania, and Missouri limit Medicaid coverage to the Hyde provisions, but an abortion provider in Alabama noted that she has never been able to obtain reimbursement even under the permitted circumstances. Focus group participants cited cost as a major barrier to accessing abortion care, with procedure costs reportedly ranging anywhere from $400 to $1,500. Many women face additional costs associated with transportation, childcare, and overnight lodging when state laws require women to wait 24-72 hours between state-mandated counseling and obtaining the abortion, as is the case in Missouri, Alabama, and Pennsylvania. There are local and national organizations that provide financial and practical assistance to some women seeking abortion; however, they do not have the resources to assist all the women who seek abortion and who cannot afford the services and the associated travel and lodging costs. Even when funds are available, logistical challenges may remain. For example, an Alabama-based organization provides financial assistance for transportation to women traveling long distances for abortions, but described barriers transferring funds to low-income women who do not have bank accounts.

|

Community Perspectives on Addressing Barriers to Abortion Services |

|

Community Strengths and Initiatives

Across the communities, providers and community organizations were engaged in initiatives intended to address barriers to reproductive health care. Although interviewees emphasized that much more needs to be done to eliminate the structural, cultural, political, and economic barriers to reproductive health services for low-income women, there were multiple organizations and individuals in each community leading various efforts to fill gaps and meet community needs. In many cases, community-based organizations took active roles in family planning, STI, or HIV education and advocacy, while others provided direct, practical assistance. Some of these strategies include:

- Supporting Positive Opportunities with Teens (SPOT) is a freestanding clinic in St Louis, Missouri, that provides teen-friendly primary care, mental health care, and express STI testing at no cost. They also offer case management to address social determinants of health. The clinic has a school-based health center (SBHC) in an area public high school, which is one of the first comprehensive SBHC programs in the area. SPOT served 3,253 St. Louis teens in 2018 (80% African American, 15% LGBT and unstably housed, and 2-3% gender nonconforming youth).

- ACT for Women and Girls (ACT), a reproductive justice grassroots organization in Tulare County, California, offers youth-led programming with a focus on reproductive health and provides comprehensive sex education in schools. The organization also has conducted a pharmacy access project since 2009 where youth secretly shop at 60-70 pharmacies each year in Tulare County to assess availability of over the counter emergency contraception (EC).

- Medical Advocacy and Outreach (MAO) is a non-profit health and wellness organization based in Montgomery, Alabama. Together with their regional partner, Selma AIDS Information and Referral (AIR), the two organizations make up a comprehensive network of full-service and Bluetooth-enabled telehealth satellite clinics providing health and social services to individuals diagnosed with HIV. This includes medical services such as primary care, gynecological and sexual health services, dental care, and mental health and substance use treatment. They also provide social services such as group and peer counseling, transportation to appointments, housing support, medication assistance, and a food bank. Special outreach and services are provided for pregnant women and formerly incarcerated individuals.

- Messengers for Health is a non-profit organization addressing health equity among the Crow tribe in Montana. They rely on “messengers” from the community to educate the Crow people about risk factors for cancer and assist them to seek out preventive screening. Their first program educated Crow women and girls about the prevention of cervical cancer and related sexual risk factors using a culturally competent curriculum. They also started the Crow Warriors for Health program to increase colorectal, prostate, and lung cancer knowledge among men in the community. In Crow culture, cancer reportedly used to be considered a taboo topic, but due to the work of Messengers for Health, women and men are now discussing it openly and regularly seeking preventive screenings such as pap tests, mammograms, and colorectal screenings.

- Multi-Cultural Health Evaluation Delivery System (MHEDS) in Erie, Pennsylvania, is an FQHC “look-alike” center that conducts health screenings for the area’s refugee population, which grew considerably in the early years of the decade. The health center has tailored its services and staffing to address the particular concerns of Erie’s refugee communities, who come from a wide array of countries, including Nepal, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Bhutan, and others. MHEDS offers interpreters to help bridge language and cultural barriers and is working to shore up provider capacity on specific topics that affect some communities, such as female genital mutilation and differing views on the provision of prenatal care.

Conclusion

A close examination of low-income women’s experiences with reproductive health care in five diverse communities reveals challenges and strengths that are not evident in statistics alone. In-person interviews, focus groups, and first-hand, on-the-ground experiences in each of the communities uncovered barriers to care common to all the communities, as well as obstacles unique to specific locales and populations. These case studies also revealed some surprises. For example, Missouri, which has not expanded Medicaid under the ACA, places significant limits on abortion and prohibits Medicaid payments to its sole abortion clinic for non-abortion services such as contraceptives; yet the St. Louis region is home to a wide variety of providers and community-based organizations that are working to improve access to the full range of family planning services. In contrast, California, expanded Medicaid eligibility under the ACA, imposes few state-level restrictions on abortion access, and operates the nation’s largest Medicaid-funded family planning program; nonetheless, access to abortion services for women in Tulare County is limited, as the nearest abortion provider is at least 50 miles away. These findings underscore that particularly for rural or underserved communities throughout the country, federal and state policies alone do not guarantee or determine access, but rather intersect with local influences.

The factors influencing reproductive health access are a complex web of social determinants of health; coverage policies; state and local investments and leadership; provider supply and distribution; sex education; the political, cultural, and religious environment; and the legacy of discrimination in many parts of the country. Across all of these communities, we met many leaders working in challenging environments to assure that reproductive care is high quality and equitable and that information is accessible to all members of their community. Importantly, talking to low-income women on the ground underscored what they expect of the health care system in providing access to reproductive health services, and the challenges in making affordable access a reality.