Being Low-Income and Uninsured in Missouri: Coverage Challenges during Year One of ACA Implementation

Who are the low-income uninsured in Missouri?

Because coverage options for the low-income uninsured in Missouri are largely the same as before the ACA, few people gained coverage in 2014, and the profile of the low-income population without coverage is largely the same as it was before the ACA. As in the past, being uninsured is a long-term problem: seven in ten of the low-income uninsured report having been uninsured for more than one year. The majority of the low-income uninsured are non-Hispanic White, about half are male, and the majority are under 35. About four in ten low-income uninsured have dependent children, as does about four in ten low-income privately insured, but the children of the low-income privately insured are more likely to be insured.

The uninsured have been without coverage for long periods of time. While some people experience short spells of uninsurance due to job changes or other changes in life circumstances, as was the case before the ACA,1 lack of coverage is a chronic problem for most low-income uninsured adults. Only about a quarter of the low-income uninsured (27%) was uninsured for less than one year. Three in ten were uninsured for one to five years, about three in ten (29%) were uninsured for more than five years but have had coverage in the past, and about one in ten had never been insured (see Additional Table A1). As discussed below, most low-income adults have few options for affordable coverage.

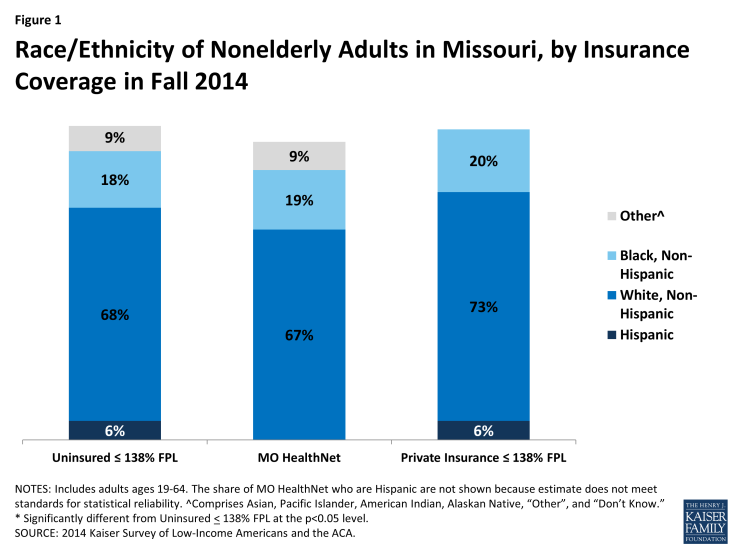

Reflecting the general demographics of the state, the majority of the low-income uninsured population is non-Hispanic and White. About 70 percent of the low-income uninsured are non-Hispanic Whites. Similarly, about 70 percent of MO HealthNet enrollees and of the low-income privately insured are non-Hispanic Whites. Though non-Hispanic Black adults account for about 11% of the overall adult population in the state, about 20% of each of the coverage groups is comprised of non-Hispanic Blacks (Figure 1). This pattern reflects the link between race and income, since Black adults in the state are more likely to be low-income than adults of other race/ethnicities (data not shown).

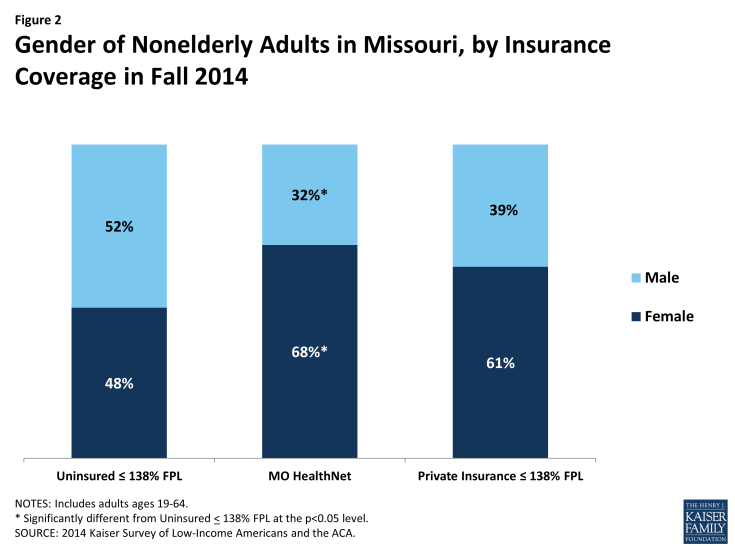

About half of the low-income uninsured are male. A slight majority (52%) of the low-income uninsured are male. In contrast, only a third (32%) of MO HealthNet enrollees are male, as women are more likely to meet family-related eligibility criteria such as being pregnant or being a caretaker parent (Figure 2). Male adults without children may obtain MO HealthNet eligibility through a disability pathway. Women make up about six in ten (61%) of the low-income privately insured, but this share is not significantly different from the uninsured.

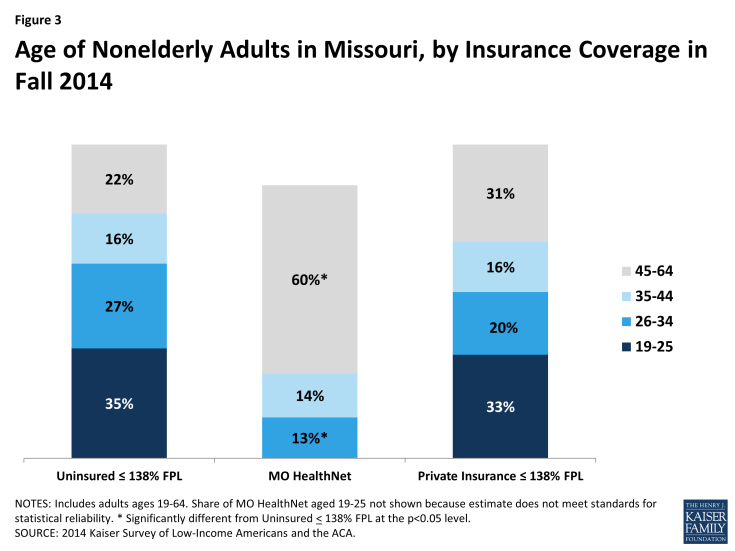

The majority (62%) of low-income uninsured are under the age of 35. Only 22 percent of the low-income uninsured are ages 45-64, compared with 60 percent of those enrolled in MO HealthNet (Figure 3). Although not statistically different from the low-income uninsured, nearly a third of the low-income privately insured are ages 45-64. Younger adults have looser ties to employment than older adults and thus are more likely to be low-income or in jobs with limited benefits. Additionally, though the uninsured tend to be thought of as the “young invincibles,” the majority (60%) of the mid-income uninsured, most of whom are eligible for subsidies, are over 35 (see Additional Table A1).

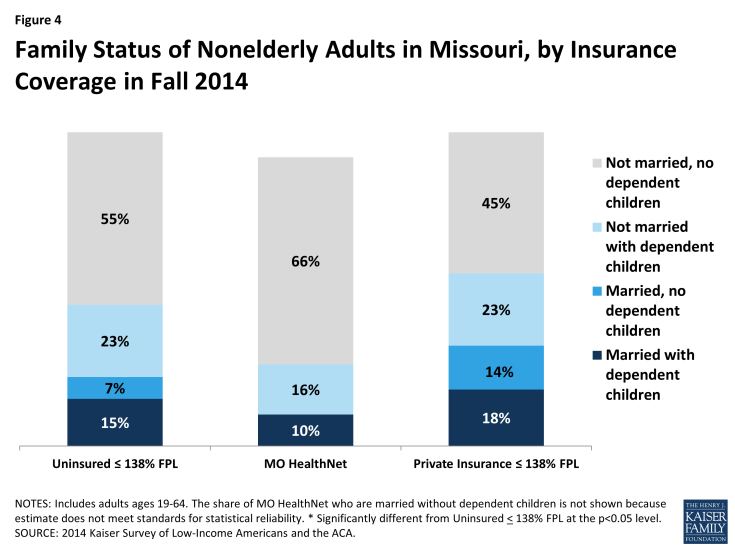

Although the patterns of marriage and having children are similar between the low-income uninsured and the low-income privately insured, the latter’s children are more likely to all have health insurance. About three quarters (78%) of the low-income uninsured are not married, and nearly four in ten (38%) have dependent children. Similarly over two thirds (68%) of low-income privately insured are not married, and over four in ten (41%) report having dependent children (Figure 4). Nearly three quarters (73%) of those enrolled in MO HealthNet say they do not have children, likely reflecting Missouri’s low income eligibility limit for adults with dependent children. Many adults enrolled in MO HealthNet do so because they have a disability, handicap, or chronic disease (data not shown). Other women without children may qualify through their pregnancy.

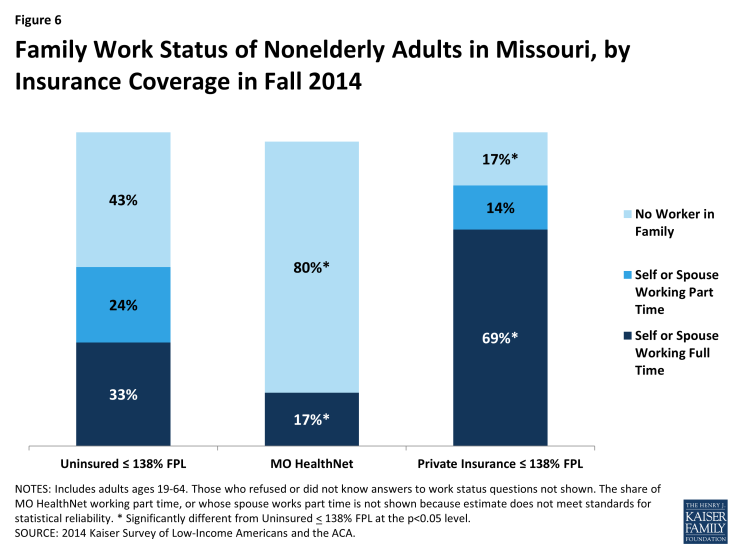

Of those enrolled in MO HealthNet who have children, nearly all have health insurance provided to their children. Similarly, nearly all low-income parents with private coverage have insured children. However, about a third of the low-income uninsured who have children do not have insurance provided to all of their children (Figure 5). Given children’s eligibility levels for MO HealthNet, most of these children are likely eligible for public coverage. This finding supports the generally known pattern that children whose parents have health insurance are more likely to be covered themselves. Additionally, research has shown that among children who are already insured, those whose parents are also insured are more likely to be linked to the health care system and receive needed care.2

Figure 5: Insurance Status of Missouri Nonelderly Adults’ Children, by Insurance Coverage in Fall 2014

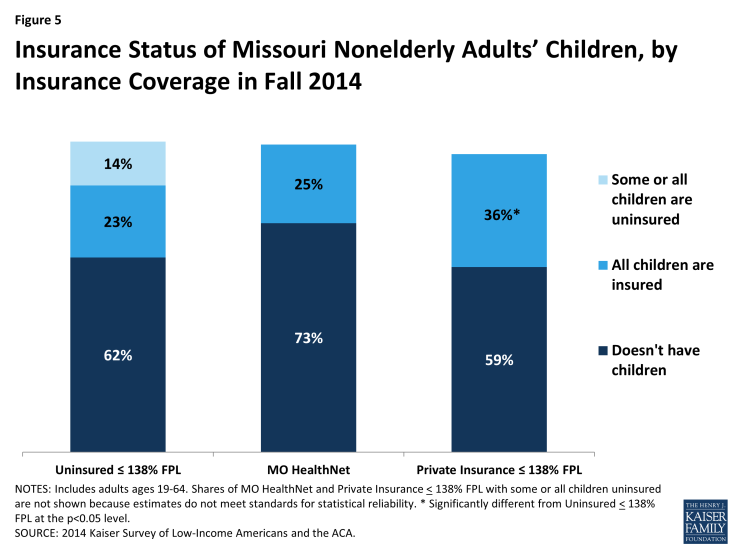

Over half of the low-income uninsured live in families with at least one person working full or part-time. One third of the low-income uninsured either works full-time or has a spouse who works full-time. Nearly a quarter (24%) of the low-income uninsured works part-time or their spouse works part-time. In contrast, nearly seven in ten low-income privately insured is in a family where they or their spouse works full-time, and about a seventh (14%) of the low-income privately insured works part-time or their spouse works part time. Health insurance is more frequently provided as a fringe benefit to full-time workers than to part-time workers, as reflected in the higher share of full-time workers within the low-income privately insured. At 80 percent, a far larger share of MO HealthNet enrollees report neither working nor having a working spouse compared to the low-income uninsured, of whom 43 percent report not having a worker in the family (Figure 6). This pattern reflects high disability rates among the adult MO HealthNet population, which may prevent many from working. It also reflects the very low Missouri Medicaid eligibility level for non-elderly adults with dependent children. In Missouri, a non-elderly adult with dependent children can earn no more than 23% of poverty, or about $4,600 a year or $380 a month for a family of three and still be eligible for Medicaid.

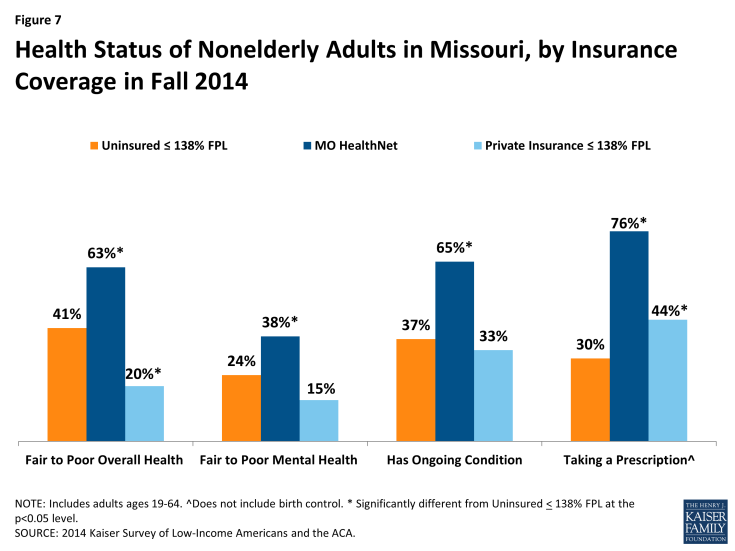

Reflecting Medicaid’s role in caring for people with substantial health needs, MO HealthNet enrollees report having poorer health status than other adults. However, the low-income uninsured likely have unmet health needs. Over six in ten (63%) of MO HealthNet enrollees have fair to poor health, compared with four in ten (41%) low-income uninsured and two in ten (20%) low-income privately insured. While 37 percent of the low-income uninsured report having an ongoing condition, only 30 percent take a prescription. In contrast, a greater share of people who are enrolled in MO HealthNet report taking prescriptions than report having an ongoing condition when enrolled in MO HealthNet. The same is true of those who are low-income privately insured (Figure 7). This suggests the possibility that the low-income uninsured have known unmet needs, as well as undiagnosed conditions.3 Notably, middle-income uninsured adults were more likely than low-income uninsured adults to report excellent or very good health and less likely to report ongoing conditions (Additional Table A1).