Asian Immigrant Experiences with Racism, Immigration-Related Fears, and the COVID-19 Pandemic

Experiences with Racism and Discrimination

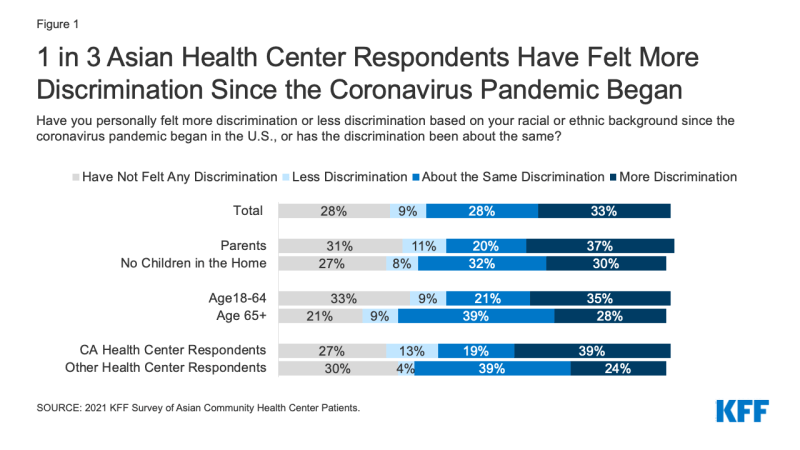

One in three (33%) Asian health center respondents say they have personally felt more discrimination based on their racial/ethnic background since the COVID-19 pandemic began in the U.S (Figure 1). Roughly three in ten indicate that they have not felt any discrimination (28%) or that they have felt about the same level of discrimination (28%), while less than one in ten (9%) report less discrimination.

Figure 1: 1 in 3 Asian Health Center Respondents Have Felt More Discrimination Since the Coronavirus Pandemic Began

The share reporting more discrimination since the pandemic began is somewhat higher among parents (37%) than those without children in the home (30%) and among adults under age 65 (35%) compared to adults over age 65 (28%). Chinese respondents are more likely than Vietnamese respondents to say that they have felt about the same level of discrimination since the start of the pandemic (30% vs. 19%) but less likely to say they have felt no discrimination (28% vs. 36%). Those who are 65 or older are more likely than those under age 65 to say that the amount of discrimination they feel has not changed, while those under age 65 are more likely to say they have not felt any discrimination since the pandemic began. California health center respondents are more likely to report both more and less discrimination since the start of the pandemic compared to those in other locations (Texas and Washington), while those in other locations are more likely to say they have felt the same level of discrimination.

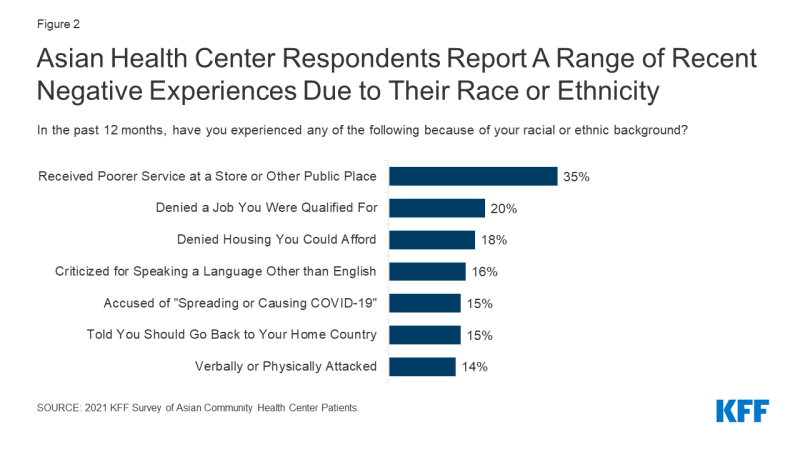

Asian health center respondents say they have faced a range of negative experiences due to their racial or ethnic background over the past 12 months, including verbal and physical attacks. Over one in three (35%) report receiving poorer service than other people due to their racial or ethnic background at a store or other public place, one in five (20%) say they have been being denied a job for which they were qualified, and 18% report being denied housing they could afford. Others report more personal attacks based on their race/ethnicity, including 16% who say they were criticized for speaking a language other than English in public, 15% who say they have been accused of “spreading or causing COVID-19” or were told that they should go back to their home country, and 14% who say they were verbally or physically attacked (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Asian Health Center Respondents Report A Range of Recent Negative Experiences Due to Their Race or Ethnicity

Those who are age 65 or older are more likely to say they have received poorer service (44% vs. 30%) or been denied housing (30% vs. 11%) or a job (27% vs. 16%) based on their race/ethnicity compared to younger respondents, and men are more likely than women to report receiving poorer service (41% vs. 32%) and being denied housing (22% vs. 15%) (Figure 3). Similarly, respondents without children in the home were more likely than parents to report housing discrimination (21% vs. 13%). California health center respondents were less likely to say they experienced discrimination in housing (11% vs. 27%) or jobs (18% vs. 23%) compared to those of other health center locations (Washington and Texas).

Over four in ten (42%) Asian health center respondents say they have been criticized for wearing a mask since the pandemic began in the U.S., while 13% say they have been criticized for not wearing a mask. There are some variations in experiences among respondents. For example, higher shares of those age 65 and older say they have been criticized for wearing a mask compared to those who are younger (57% vs. 32%) and men are more likely to say they have been criticized for mask wearing than women (47% vs. 38%). Respondents without children in the home also are more likely than parents to report being criticized for wearing a mask (48% vs. 29%). There are also variations in experiences by location, with California health center respondents less likely than those in other locations to report being criticized for wearing a mask (30% vs. 57%) and more likely to say they have been criticized for not wearing one (16% vs. 7%).

Immigration-Related Fears

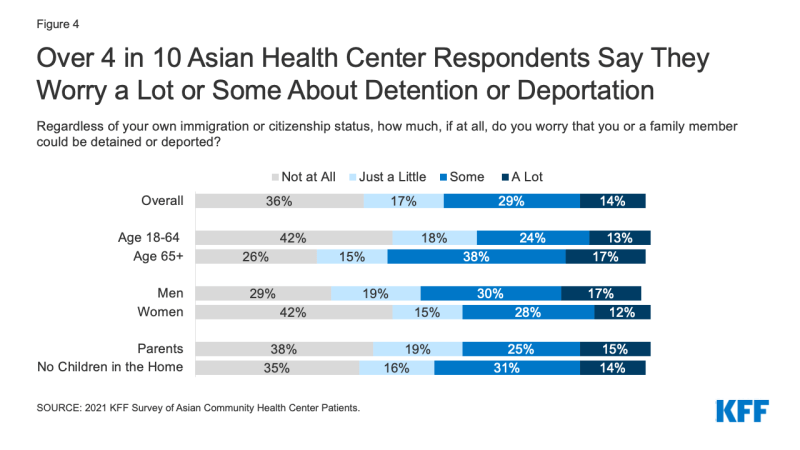

Over four in ten (44%) Asian health center respondents say they worry a lot or some that they or a family member could be detained or deported (Figure 4). Worries are higher among those age 65 or older, men, and those without children in the home, compared to those who are under age 65, women, and parents. Among parents, three in ten (30%) say their children have worries or fears that they or a family member might be detained or deported. Although there is no significant difference in their own levels of worry about detention or deportation by location, parents who are California health center respondents are more likely to say their children are concerned about a family member being detained or deported than parents in other locations (39% vs. 12%).

Figure 4: Over 4 in 10 Asian Health Center Respondents Say They Worry a Lot or Some About Detention or Deportation

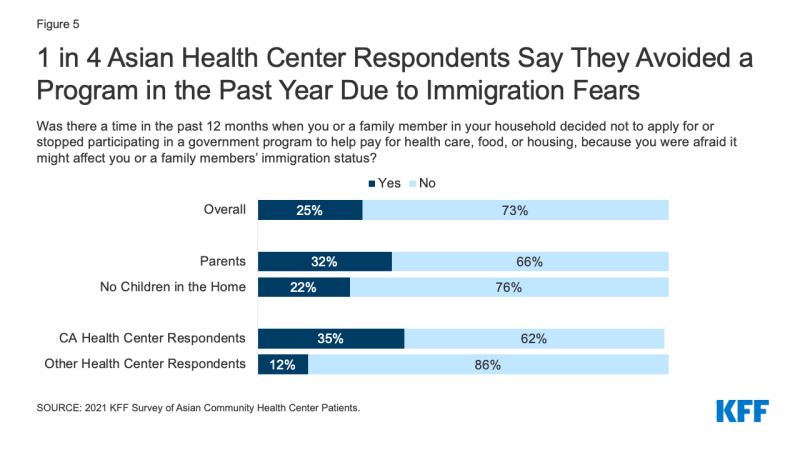

One quarter (25%) of respondents say they or a member of their household decided not to apply for or stopped participating in a government program to help pay for health care, food, or housing in the past year due to immigration-related fears (Figure 5). Overall, nearly one in five (17%) say they did not apply for or stopped participating in a program that helps with housing, 12% for a program that helps with food, and 10% for a program that helps pay for health care. The shares who say they did not apply for or stopped participating in a program are higher among parents (32%) and respondents at California health centers (35%). However, parents also are more likely than those without children in the home to say they have received any type of government assistance to pay for things like housing, food, or health insurance in the past year (53% vs. 34%), as are California health center respondents compared to those in other locations (48% vs. 29%).

Figure 5: 1 in 4 Asian Health Center Respondents Say They Avoided a Program in the Past Year Due to Immigration Fears

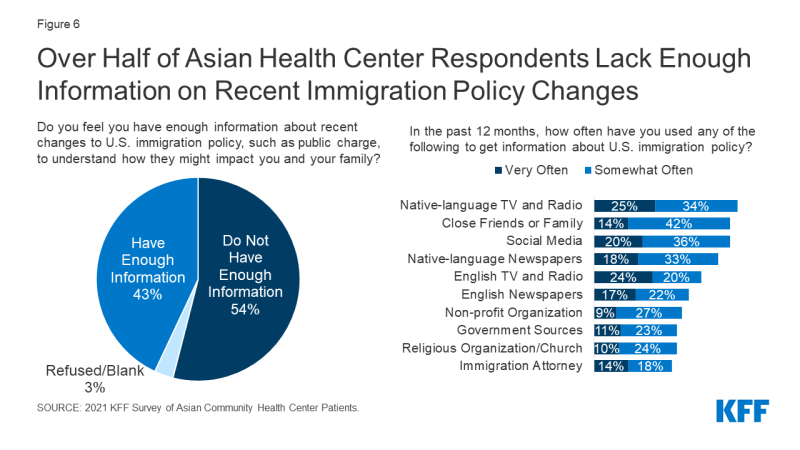

Over half of (54%) respondents say they do not have enough information about how recent changes to U.S. immigration policy might impact them or their family (Figure 6). Chinese respondents are more likely than Vietnamese respondents to say they do not have enough information (59% vs. 41%).

Figure 6: Over Half of Asian Health Center Respondents Lack Enough Information on Recent Immigration Policy Changes

Asian health center respondents report relying on a variety of sources for information on immigration policy. The most frequently cited sources that they relied on very or somewhat often were television and radio in their native language (59%) followed closely by friends and families (56%) and social media (56%). Over half (51%) report relying on newspapers in their native language, and nearly half said they rely on English television and radio (44%) or English newspapers (40%) very or somewhat often. About four in ten report turning to nonprofit organizations (36%) or the government (34%) for this information, while over one in three said they rely on religious organizations (34%) or an attorney (32%).

In general, respondents age 65 or older are more likely to report using all sources of information very or somewhat often compared to their younger counterparts, except for social media or close family or friends. In addition, those without children in the home and men are more likely to report frequent use of certain information sources than parents and women, particularly English language television, radio, and newspapers. California health center respondents are less likely than those of other health centers to report frequent use of certain sources of information, including English language television and radio (16% vs. 35%), English language newspapers (10% vs. 27%), native language television or radio (21% vs. 30%), a nonprofit organization (6% vs. 13%), a religious organization or church (7% vs. 13%), government sources (5% vs. 20%), or an immigration attorney (5% vs. 25%).

Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic

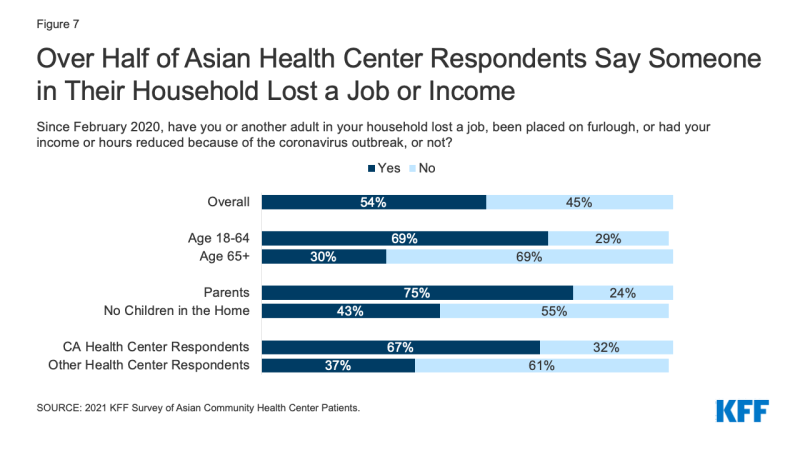

Over half (54%) of Asian health center respondents say they or another adult in their household lost their job or had their income or hours reduced due to the pandemic (Figure 7). This share rises to 75% for those who are parents and nearly seven in ten among those under age 65 (69%) and who are California health center respondents (67%).

Figure 7: Over Half of Asian Health Center Respondents Say Someone in Their Household Lost a Job or Income

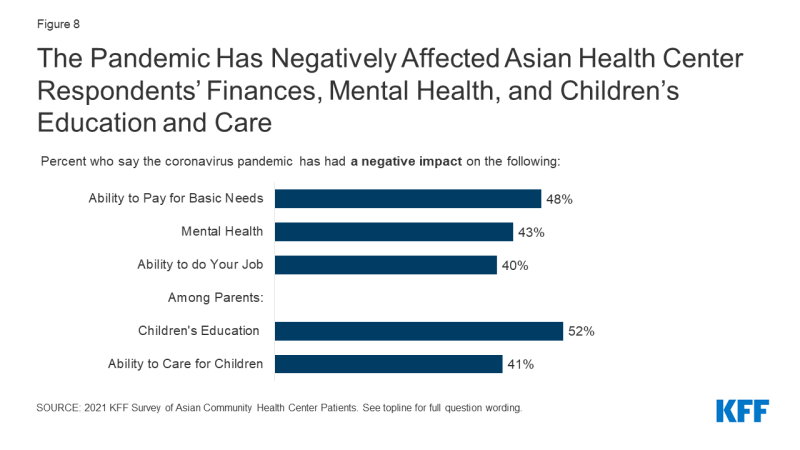

Respondents also report negative impacts on their ability to pay for basic needs, their mental health, and their children’s education and care (Figure 8). Nearly half (48%) say that the COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected their ability to pay for basic needs like housing, utilities, and food, four in ten (40%) report that it negatively affected their ability to do their job, and 43% say it has negatively impacted their mental health. The share reporting negative impacts on ability to pay for basic needs rises to over half among parents (53%) and men (53%). Vietnamese respondents are more likely than Chinese respondents to report negative impacts on their ability to pay for basic needs (61% vs. 44%) and their ability to do their job (51% vs. 37%), while Chinese respondents are more likely to report positive effects in these areas as well as on their mental health (30% vs. 20%).

Figure 8: The Pandemic Has Negatively Affected Asian Health Center Respondents’ Finances, Mental Health, and Children’s Education and Care

Over half of parents (52%) say the pandemic has negatively affected their children’s education and 41% say it has had negative impacts on their ability to care for their children. In contrast, three in ten say the pandemic has positively impacted their children’s education (30%) and their ability to care for their children (30%). California health center respondents are more likely than those of other health centers to report positive impacts on their children’s education (35% vs. 17%) and care (35% vs. 19%), while other health center respondents are more likely than California health center respondents to report no impact on education (26% vs. 11%) or care (39% vs. 20%).

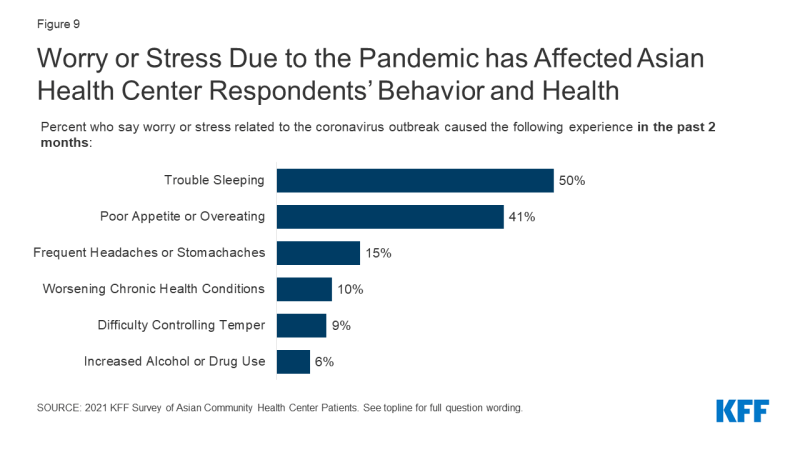

Many respondents say worry and stress related to the pandemic has affected their behavior and health in certain ways. Nearly half (48%) say it has affected their sleep and 39% report changes in their appetite and eating (Figure 9). Others say it has led to frequent headaches or stomachaches (24%), increased difficulty controlling temper (15%), increased alcohol or drug use (10%), and worsened chronic conditions, like diabetes or high blood pressure (9%). Adults under age 65 are more likely than those age 65 and older to report some of these effects, including frequent headaches or stomachaches, difficulty controlling temper, and increased alcohol and drug use. There were also some differences by location, with California health center respondents more likely to report these same effects, which may also reflect that they are more likely to be under age 65.

Figure 9: Worry or Stress Due to the Pandemic has Affected Asian Health Center Respondents’ Behavior and Health

Three in ten (30%) Asian health center respondents say they put off or went without health care in the past 12 months and 37% of parents report doing so for their children. Among those who put off or went without health care for themselves, 42% say they did not seek health care because of concerns about exposure to coronavirus. Other factors include not being able to take time off work (45%) and not being able to afford the cost (31%), despite being patients of a community health center that provides free or low-cost care. Less than one in ten (6%) say they went without care because they were concerned it would negatively affect their or a family member’s immigration status. Adults under age 65 are more likely to say they put off or went without care than those age 65 and older (35% vs. 23%), and a higher share of parents say they went without care than those without children in the home (39% vs. 26%). Parents are more likely than those without children in the home to say they went without care because they couldn’t take time off work or due to difficulty getting to an office or clinic and less likely to cite concerns about exposure to coronavirus as a reason. California health center respondents are more likely than those at other centers to report putting off or going without health care for themselves (42% vs. 15%) and their children (44% vs. 20%). These differences may reflect demographic differences—California health center respondents are more likely to be under age 65 and parents—as well as differences in social distancing policies across locations.

COVID-19 Exposure, Testing, and Vaccines

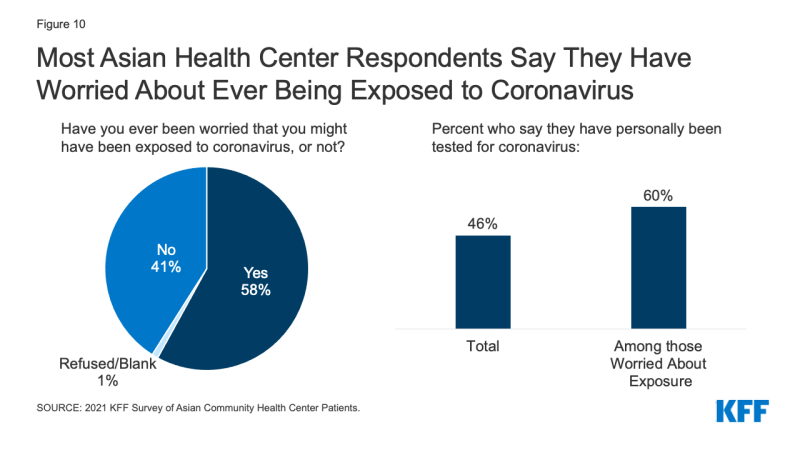

Nearly six in ten (58%) Asian health center respondents say they have worried at some point about being exposed to coronavirus (Figure 10). Overall, less than half (46%) say they have ever been tested for coronavirus, but the share rises to 60% among those who say they have ever worried about exposure. Among those who worried they might have been exposed but were not tested, the main reasons they give for not getting tested are thinking they could isolate at home (31%) or not knowing where to go to get tested (26%). Some also report concerns about costs (13%) and being told by a health professional they did not need to get tested (13%). About one in ten say they had concerns about effects on their ability to work (12%) or fears of negative effects on their or a family member’s immigration status (10%), even though the federal government has clarified that getting tested will not negatively affect immigration status.

Figure 10: Most Asian Health Center Respondents Say They Have Worried About Ever Being Exposed to Coronavirus

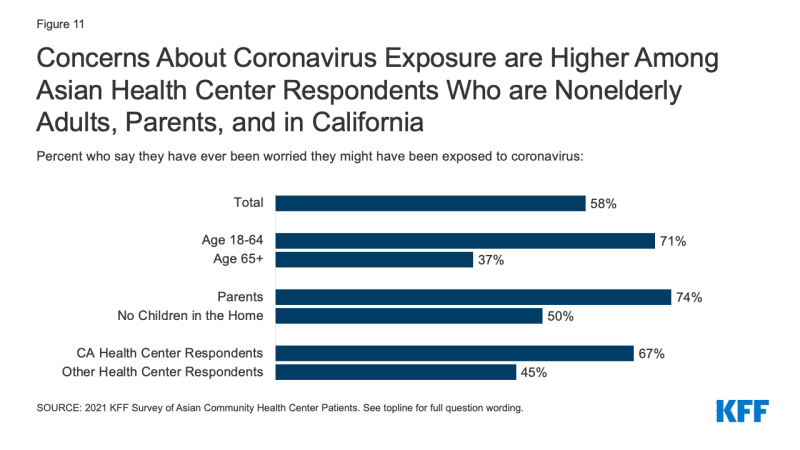

Concerns about ever being exposed to coronavirus are higher among adults under age 65, parents, and California health center respondents (Figure 11). Reflecting these increased worries, these groups are also more likely to report having received a COVID-19 test, overall. There are no notable differences by age or parental status in the share who say they have received a test among those who ever worried about exposure. However, among those who say they have ever worried about exposure, California health center respondents are more likely to report being tested than those of other health centers (66% vs. 49%).

Figure 11: Concerns About Coronavirus Exposure are Higher Among Asian Health Center Respondents Who are Nonelderly Adults, Parents, and in California

At the time of the survey, nearly two-thirds (64%) of respondents said they wanted to get the COVID-19 vaccine as soon as they can. About a quarter (23%) indicated they want to wait to see how it works for other people. Only 11% said they will only get the vaccine if required or definitely will not get it. Concerns about side effects, believing that the vaccine development process was rushed, and not believing they are at risk for getting seriously ill from the virus are the main reasons why people say they are not ready to be vaccinated. Broader data show that vaccine attitudes have shifted over the course of the vaccine rollout, with willingness to get a vaccine increasing across a number of groups.

Conclusion

While these findings are not representative of Asian immigrants or Asian health center patients overall, they provide new insight into and understanding of the experiences of Asian health center patients who are largely immigrants, a group for whom there remain very little data. The findings illustrate the ways Asian immigrants experience racism and discrimination in their daily lives and indicate that these experiences have increased amid the COVID-19 pandemic. They also suggest that immigration-related fears are ongoing among the community and contributing to reluctance accessing government assistance programs for food, housing, and health care. The findings further show the that the pandemic has taken a toll on mental health and well-being, finances, and access to health care for Asian immigrant families. This increased understanding can help inform COVID-19 response efforts as well as efforts to address health disparities more broadly. Going forward, continued efforts to assess and understand the experiences of smaller population groups, including Asian immigrants, remain important as they are often invisible in public data sources.