An Overview of Medicaid Incentives for the Prevention of Chronic Diseases (MIPCD) Grants

MIPCD Grants

Introduction

Faced with rising health care costs and disparities in health outcomes, policymakers have increasingly focused on the benefits of investing in preventive care. In particular, states are expanding efforts to engage Americans in their behaviors and emphasize the importance of personal choices in determining health. Several Medicaid programs have implemented incentives for beneficiaries who demonstrate healthy behaviors. Incentive programs often focus on preventative care and disease management, and some target specific behaviors such as smoking and weight loss. Programs vary by the authority under which they operate and the incentives used, such as cash, gift cards, or flexible spending accounts. To expand these programs, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) established the Medicaid Incentives for Prevention of Chronic Diseases (MIPCD) grant. This grant allows states to provide incentives to Medicaid beneficiaries who participate in prevention programs and demonstrate changes in health risk and outcomes. The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation awarded MIPCD grants to ten states in September 2011 and the program runs through January 1, 2016 (see Appendix for more details on state programs). In November 2013, an interim evaluation was conducted on MIPCD programs to date. This brief highlights key findings from the evaluation and puts them in context of past and proposed beneficiary incentive programs in Medicaid.

Background

Chronic Disease and Preventive Care in the United States

Chronic diseases and conditions, such as heart disease, stroke, and diabetes, are among the most common, costly, and preventable of all health problems.1 As of 2012, about half of all U.S. adults (117 million people) had one or more chronic health conditions, and one in four adults had two or more chronic health conditions.2 Health risk behaviors are unhealthy behaviors that can be changed, and four of these risk behaviors (lack of exercise or physical activity, poor nutrition, tobacco use, and overconsumption of alcohol) cause much of the illness, suffering, and early death related to chronic diseases and conditions.3

Individuals in the U.S., particularly low-income populations, face barriers to receiving the recommended amount of health care. American adults receive only half of recommended health care, including preventive care, acute care, and treatment for chronic conditions.4 Low-income populations and racial and ethnic minorities in particular face inequalities in access to and quality of services, preventive care, health outcomes, and risk of unhealthy behaviors.5 Low socioeconomic status, in part due to health care access, cost, and infrastructure barriers, has been associated with higher risks of smoking, obesity, and certain chronic conditions.6

Medicaid Beneficiary Incentive Programs Prior to the ACA

Prior to the ACA, several Medicaid programs implemented beneficiary incentive programs to engage Americans in their behaviors and emphasize the importance of personal choices in determining health.7 These programs were meant to empower individuals to change their lifestyle habits to achieve better health and often focused on preventative care, prenatal and postpartum care, smoking, obesity, and specific chronic conditions. Some of these programs, such as Idaho’s Preventative Health Assistance (PHA) Benefits8 and Indiana’s Healthy Indiana Plan (HIP), are still operating. Pre-ACA Medicaid beneficiary incentive programs have achieved mixed results, and some have faced criticisms or skepticism from the health policy community and patient advocates.9

Medicaid healthy behavior incentives are often offered in the form of cash reward, pre-paid debit card, or gift certificate for use towards health-related purchases, such as medicine, healthy food, or gym memberships. Some states, such as Idaho, offer beneficiaries points or credits, which may be accumulated to redeem similar rewards.10 For children in families that pay a Medicaid premium, Idaho also offers reduced premiums for keeping well-child check-ups and immunizations current. West Virginia offered enhanced or restricted benefits to promote healthy behaviors through its Mountain Health Choices program, which ended on January 1, 2014.11 Indiana’s Healthy Indiana Plan (HIP) currently offers health savings accounts (HSAs) to pre-ACA Medicaid expansion adults. Both the state and the beneficiary contribute to this account. If beneficiaries complete all age and gender appropriate preventive services, all remaining account funds (both state and individual) are rolled over to the next year. However, if preventive services are not completed, only the individual’s prorated contribution (not the state’s) rolls over.12

Medicaid programs operate beneficiary incentive programs under various authorities. To date, most states have used Section 1115 Medicaid demonstration waivers that include beneficiary incentives for healthy behaviors to operate their programs.13 Some states have used Section 1915(b) waivers and Medicaid managed care organizations to offer incentives.14 Other states have operated incentive programs as state plan amendments under the Deficit Reduction Act (DRA)15 or as pilot or demonstration programs.16

Some pre-ACA Medicaid beneficiary incentive programs, such as Florida’s Enhanced Benefits Reward$ and West Virginia’s Mountain Health Choices, have ended or are phasing out. Florida is currently transitioning most of its Medicaid beneficiaries into managed care through the renewal of its “Managed Medical Assistance” (MMA) Section 1115 waiver. The renewed waiver calls for the Enhanced Benefits Reward$ program to phase out, but will require managed care plans operating in MMA program counties to administer programs to encourage and reward healthy behaviors.17 West Virginia’s Mountain Health Choices required beneficiaries to sign a membership agreement promising to adhere to certain behaviors (such as keeping doctor appointments and complying with medication) and a health improvement plan. If beneficiaries complied with these agreements, they received an enhanced benefit plan, but if they did not comply with the agreements, they received a benefit plan covering fewer services than the traditional Medicaid plan.18 In 2010, federal regulations required adult enrollments into such programs to be voluntary, which resulted in the state discontinuing the program on January 1, 2014.19

Evidence on Consumer Incentive Programs

Overall (both inside and outside of Medicaid), consumer incentive programs are fairly new and research on their effectiveness in encouraging behavior change has varied. In the short run, consumer incentives can be effective for encouraging one-time or simple preventative care, such as receiving immunizations or attending a regular check-up. However, there is insufficient evidence to say if incentives are effective for promoting long-term lifestyle changes, such as smoking cessation or weight management.20 Additionally, studies of consumer incentives often have limitations such as small sample sizes and limited follow-up.21 Evidence on Medicaid incentive programs specifically has varied as well. Some Medicaid programs have received positive participant feedback and have shown high rates of physician visits and preventative care, while other programs have found little evidence of beneficiary behavior change or health improvement. Many Medicaid programs have faced skepticism that incentives will encourage healthy behavior changes.22

Estimates on the cost-effectiveness of Medicaid beneficiary incentive programs have also varied. States aim to reduce Medicaid costs by encouraging the use of preventative care in order to decrease the need for future high-cost treatments and hospital use. However, government agencies, policy analysts, and patient advocates have questioned the cost-effectiveness of incentive programs given their infrastructure start-up costs, marketing costs, and administrative costs.23

Some private incentive programs offered through drug treatment programs or workplace settings have demonstrated success in improving health behaviors,24 but Medicaid programs could encounter unique challenges in implementing such incentives. Low-income individuals face obstacles that could limit their participation or hinder their ability to meet the requirements necessary to achieve incentives. For example, Medicaid beneficiaries may have difficulty affording transportation or child care to attend doctor appointments, have insufficient access to phones or computers to complete required activities, or have difficulty affording health activities or medications that may not be covered by Medicaid, but which would help them to achieve their goals, such as weight loss programs or educational classes. Additionally, private programs are likely to offer greater financial incentives, which could influence more substantial behavior change.

Medicaid Incentives for Prevention of Chronic Diseases (MIPCD) Grants

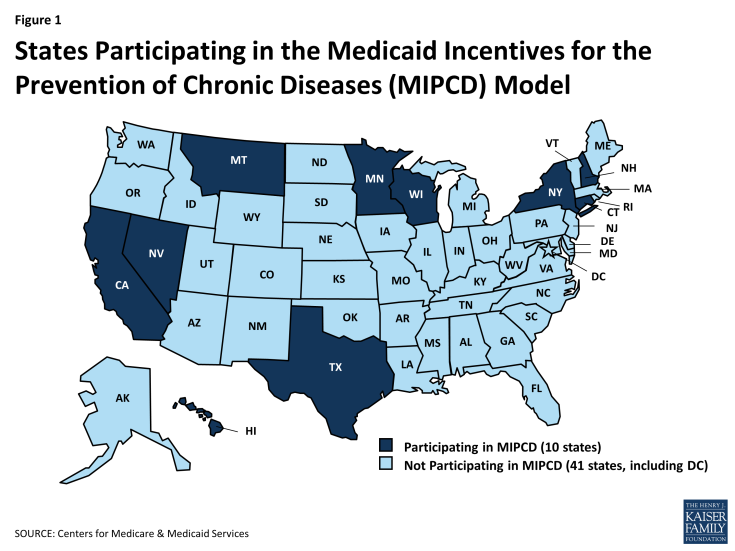

Section 4108 of the Affordable Care Act created the Medicaid Incentives for Prevention of Chronic Diseases (MIPCD) program. The grant program provides a total of $85 million over five years to ten states to test the effectiveness of providing incentives directly to Medicaid beneficiaries who participate in prevention programs and change their health risks and outcomes by adopting healthy behaviors.25 States must address at least one of the designated prevention goals: tobacco cessation, controlling or reducing weight, lowering cholesterol, lowering blood pressure, and preventing or controlling diabetes. In September 2011, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation awarded ten states demonstration grants: California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, New York, Texas, and Wisconsin (Figure 1). States are in the process of implementing their incentive programs and grant funding runs through January 1, 2016. An interim evaluation was conducted in November 2013, and a final evaluation will be completed by July 2016.

Figure 1: States Participating in the Medicaid Incentives for the Prevention of Chronic Diseases (MIPCD) Model

States are required to target at least one of the five designated prevention goals described above, however, six of the ten grantee states (Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, New York, and Texas) are targeting multiple behaviors and conditions (Table 1). Montana and Nevada are each targeting four prevention goals, and Texas is targeting all five prevention goals. Some of these programs link their focuses on healthy behaviors to improved conditions. For example, Montana will monitor weight loss, lowered cholesterol, and lowered blood pressure in an effort to prevent type 2 diabetes. Other states have separate, distinct programs that focus on different goals. New Hampshire, for example, has a weight management program and a separate smoking cessation program. The goals most commonly targeted are smoking and diabetes (six states each), and the least frequently targeted goal is high cholesterol (three states). To implement their MIPCD grants, Medicaid programs are partnering with other government agencies and private organizations to more effectively address a range of health conditions and behaviors. Partners often include state departments of public health or mental health/substance abuse, universities, research institutes, community organizations, providers, and health plans.26

| Table 1: Medical Conditions and Health Behaviors Addressed by State MIPCD Programs, 2013 | |||||

| State | Smoking | Diabetes | Obesity | High Cholesterol | High Blood Pressure |

| California | X | ||||

| Connecticut | X | ||||

| Hawaii | X | ||||

| Minnesota | X | X | |||

| Montana | X | X | X | X | |

| Nevada | X | X | X | X | |

| New Hampshire | X | X | |||

| New York | X | X | X | ||

| Texas | X | X | X | X | X |

| Wisconsin | X | ||||

| Total | 6 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 4 |

| SOURCE: Kathleen Sebelius, Initial Report to Congress: Medicaid Incentives for Prevention of Chronic Diseases Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, November 2013. http://innovation.cms.gov/Files/reports/MIPCD_RTC.pdf. | |||||

States are taking various approaches in their behavior-change interventions. Most programs focused on smoking cessation involve telephone helplines, in-person or telephone-based counseling, and nicotine replacement therapy or other medications. Connecticut is also using peer coaches, and New Hampshire is using a web-based decision support system in addition to the other services mentioned. Programs focused on diabetes tend to use educational and training programs focused on diabetes prevention or self-management. Some states are also using care coordination, health coaches, or incentives for attending primary care visits or filling prescriptions. Weight management programs most often provide gym memberships or access to weight loss or health promotion programs. Texas is having its beneficiaries create a personal wellness plan, receive a flexible spending account, and work with a health navigator to achieve personal health goals. Some states are training providers on specific treatment programs or incentivizing providers for participating in the MIPCD program.27

All MIPCD states are targeting adult Medicaid beneficiaries with or at risk of chronic diseases;28 however, many states are focusing on additional special populations with unique health care needs (Table 2). Five states are focusing on pregnant women and mothers of newborns, most of them with a focus on smoking cessation. Four states are focusing on individuals with mental illness, and two of these states are also addressing individuals with substance abuse disorders. Three states are focusing on racial/ethnic minorities and one state (Nevada) is focusing on children. Eight states are incorporating individuals dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid (“dual-eligibles”) into their programs. States also vary in the number of beneficiaries that they expect to reach. Connecticut hopes to enroll the most beneficiaries (28,771) in its program, while Montana is focusing on the smallest number of beneficiaries (726).29

| Table 2: Targeted Special Populations in State MIPCD Programs, 2013 | ||||||

| State | Individuals with Mental Illness | Individuals with Substance Abuse Disorders | Racial/Ethnic Minorities | Pregnant Women and Mothers of Newborns | Children | Dual-Eligible Beneficiaries |

| Californiaa | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Connecticutb | X | X | X | |||

| Hawaiic | X | X | ||||

| Minnesotad | X | |||||

| Montanae | X | X | ||||

| Nevada | X | X | ||||

| New Hampshire | X | X | ||||

| New Yorkf | X | |||||

| Texasg | X | X | ||||

| Wisconsin | X | X | X | |||

| Total | 4 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 8 |

|

NOTES: a CA does not consider these populations to be a primary focus, but will be able to identify these populations and provide data on their participation;

b For individuals with mental illness, CT is focusing on serious mental illness;

c HI does not consider individuals with mental illness or substance abuse disorders to be a primary focus, but will be able to identify these populations and provide data on their participation. For racial/ethnic minorities, HI is focusing primarily on indigenous Native Hawaiians, immigrant Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and migrants from Compact of Freely Associated States;

d MN does not consider racial/ethnic minorities to be a primary focus, but will examine the differences among racial and ethnic minorities to the extent that the data will support that level of analysis. MN will focus specifically on American Indian, African American, Somali, Latino, Hmong, Vietnamese, Korean, and other Asian immigrants;

e In MT, pregnant women are ineligible for the program, but mothers of newborns who meet the eligibility criteria are eligible for the program;

f NY does not consider mothers of newborns to be a primary focus, but this population may be included in its programs;

g TX will focus both on serious and persistent mental illness (ex. schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depressive disorder) and other behavioral health conditions (ex. anxiety disorder or substance abuse).

SOURCE: Kathleen Sebelius, Initial Report to Congress: Medicaid Incentives for Prevention of Chronic Diseases Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, November 2013. http://innovation.cms.gov/Files/reports/MIPCD_RTC.pdf.

|

||||||

Most states are including beneficiaries statewide, but some are focusing on targeted geographic areas (Table 3). For example, Texas, Minnesota, and Nevada are all focusing their programs in major metropolitan areas (Houston, Minneapolis-St. Paul, and Las Vegas). California and Wisconsin started their programs as a pilot in one county before rolling them out statewide. Hawaii phasing in its program by participating FQHC, and New York is phasing in its program by MCO and program focus, before both states roll their programs out statewide. Connecticut, Montana, and New Hampshire are all implementing their programs statewide with no phase-in process.30

| Table 3: Targeted Locations of State MIPCD Programs, 2013 | |

| State | Location |

| California | Began implementation as a pilot in one county and rolled out statewide |

| Connecticut | Statewide (no pilot or phases)a |

| Hawaii | Phased-in implementation by FQHC, rolling out to 14 FQHCs and the larger private providers throughout the six main inhabited islands of Hawaii |

| Minnesota | Phased-in implementation by clinic, rolling out to the 7-county Minneapolis-St. Paul metro area |

| Montana | 14 health facilities across the state (no pilot or phases) |

| Nevada | Phased-in implementation by partner organization, rolling out to the Las Vegas area |

| New Hampshire | 10 community mental health centers across the state (no pilot or phases) |

| New York | Phased-in implementation by MCO and program focus, rolling out statewideb |

| Texas | 9 counties in the Houston area (no pilot or phases) |

| Wisconsin | Beginning implementation as a pilot in one county and rolling out statewide.c |

|

a The peer coaching component of the initiative will be available only to participants in three selected counties.

b New York is collaborating with Medicaid managed care organizations, which may operate statewide, or may be located in select geographic areas.

c Wisconsin’s First Breath arm of its MIPCD program will be in Kenosha, Milwaukee, Racine, Dane, and Rock counties and will expand to additional counties, with the initial focus on those with high numbers of pregnant BadgerCare Plus members. Wisconsin’s Tobacco Quit Line arm of its MIPCD program will be implemented in Brown, Dane, Dodge/Jefferson (clinic is on border of two counties), Green, Milwaukee, Rock, and Winnebago counties where the biochemical nicotine test is currently available. Expansion to additional counties will take place in the future.

SOURCE: Kathleen Sebelius, Initial Report to Congress: Medicaid Incentives for Prevention of Chronic Diseases Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, November 2013. http://innovation.cms.gov/Files/reports/MIPCD_RTC.pdf. |

|

States are building on traditional Medicaid incentive structures, but offering a range of options to beneficiaries. Most states are using money, or money-equivalents (such as gift cards), in their programs. Programs also offer incentives related to treatment (such as nicotine patches) or incentives related to prevention (such as gym memberships or participation in Weight Watchers). Nevada is offering points redeemable for rewards through a web-based platform, while Texas is offering its participants access to a flexible spending account. Some states are also offering participants supports to address barriers to participation. Minnesota, for example, which has its beneficiaries attend Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) self-management training sessions, offers meals and child care during training sessions, as well as transportation to the sessions. In Hawaii, participating FQHCs have flexibility to determine the form of the participant’s incentive (gift certificate, fee for gym membership, etc.).31

The maximum value of incentives varies widely by state, and may help to demonstrate if the value of incentives impacts behavior change. Because states are designing different incentive structures, the maximum value of incentives varies by state. Incentives range from $20 in California for calling a smoking cessation helpline and participating in counseling sessions, to $1,860 per year in New Hampshire for participating in a weight loss program. Eight out of the ten states offer incentives that range between $215-$600 per year. States are rewarding both participation in prevention- and treatment-related activities as well as health outcomes. All states are rewarding beneficiaries for participation or behavior change (such as attending smoking cessation or diabetes self-management programs), and seven states are also offering incentives for improved health outcomes (such as weight loss, achievement of smoking cessation or a negative CO breathalyzer test, or improved blood tests). Connecticut is offering additional incentives for repeated participation or repeated improved health outcomes. Six states are offering rewards to providers to incentivize their participation in the MIPCD program as well (Table 4). Incentives for providers include $35/individual for enrolling participants in Connecticut, $308/individual for providing services to participants in Hawaii, up to $278,000 for clinics to cover study-related costs in Minnesota, and Medicaid reimbursement for providing lifestyle interventions in Montana.32

| Table 4: Provider Incentives in State MIPCD Programs, 2013 | |

| State | Provider Incentives |

| California | NA |

| Connecticut | -Free online training offered for providers on smoking cessation treatment and information on Medicaid coverage for smoking cessation services and Rewards to Quit program services.-One time $35 stipend offered to providers for each new Medicaid recipient enrolled in Rewards to Quit. |

| Hawaii | Participating FQHCs and private providers may receive up to $308 per participant for providing supportive, supplemental services to patients. |

| Minnesota | Clinics receive up to $278,000 to cover study-related costs, including participants’ supports, personnel, equipment, and supplies. |

| Montana | Through an approved state plan amendment, selected licensed health care professionals can be reimbursed by Medicaid for providing the lifestyle intervention. |

| Nevada | Select providers may receive compensation for each participant for which they enter enrollment and incentive data into a web portal. Compensation is $300 per participant for YMCA, $250 per participant for Children’s Heart Center, and $275 per participant for Lied Clinic. |

| New Hampshire | NA |

| New York | NA |

| Texas | NA |

| Wisconsin | Clinics and public testing sites receive $1,000 after receiving training and conducting testing. They may also select a “per member” option, which may provide additional support of $50-75 per member. |

| SOURCE: Kathleen Sebelius, Initial Report to Congress: Medicaid Incentives for Prevention of Chronic Diseases Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, November 2013. http://innovation.cms.gov/Files/reports/MIPCD_RTC.pdf. | |

States are required to evaluate the effectiveness of their programs, and seven out of ten states are structuring their programs as randomized controlled trials (RCTs), the gold standard of research design (Table 5).33 Of the states not conducting RCTs, Hawaii is conducting a quasi-experimental design that lacks random assignment. Montana is using a crossover design, where, during the first 18 months of the program, seven of its 14 intervention sites will be selected to provide participants with incentives and the remaining sites will not. After that, the seven sites that did not offer incentives will provide them to new participants, and the sites that did provide incentives will no longer provide them to new participants. New Hampshire is using an equipoise-stratified randomized design, where participants select their treatment options, and then half of participants are randomized as to whether they receive incentives. Eights states are also conducting a cost-effectiveness analysis of the incentive programs. States are at different phases in their evaluations due to starting at different times. Montana, California, New Hampshire, and Texas began implementation between January-May 2012, whereas some states did not begin implementation until February-September 2013.34 States are required to submit quarterly, semi-annual (every six months), annual, and final (at the end of the grant period) reports. In addition to these state evaluations, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) must procure an independent contractor to conduct a national evaluation, and submit interim and final reports of this evaluation to Congress.35

| Table 5: Evaluation Designs in State MIPCD Programs, 2013 | |||||

| State | Quasi-Experimental Designs | Randomized Controlled Trialsa | Equipoise-Stratified Randomized Designs | Crossover Designsb | Cost-Effectiveness Analysesc |

| California | X | X | X | ||

| Connecticut | X | X | |||

| Hawaii | X | X | |||

| Minnesota | X | X | |||

| Montana | X | ||||

| Nevada | X | X | |||

| New Hampshire | X | X | |||

| New York | X | ||||

| Texas | X | X | |||

| Wisconsin | X | X | |||

| Total | 2 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| a Wisconsin has changed its initiative from a clinical trial to a quality-improvement project; however, it is maintaining its randomized two-group design. b Hawaii is considering adopting a crossover design for use with a participating private group practice. c New York will conduct an informal cost-effectiveness study; a formal assessment of all the costs will not be undertaken. SOURCE: Kathleen Sebelius, Initial Report to Congress: Medicaid Incentives for Prevention of Chronic Diseases Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, November 2013. http://innovation.cms.gov/Files/reports/MIPCD_RTC.pdf. |

|||||