An Overview of Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) Waivers

Introduction

States are engaged in an array of delivery system reform efforts from managed care to new options in the ACA such as demonstrations for those dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid as well as health homes. Multi-payer initiatives are funded through the State Innovation Models initiative (SIM), and CMS, together with the National Governor’s Association (NGA), recently announced a new initiative called the Medicaid Innovation Accelerator Program that will invest over $100 million over five years to help states accelerate the development and testing of new state-led payment and service delivery innovations.

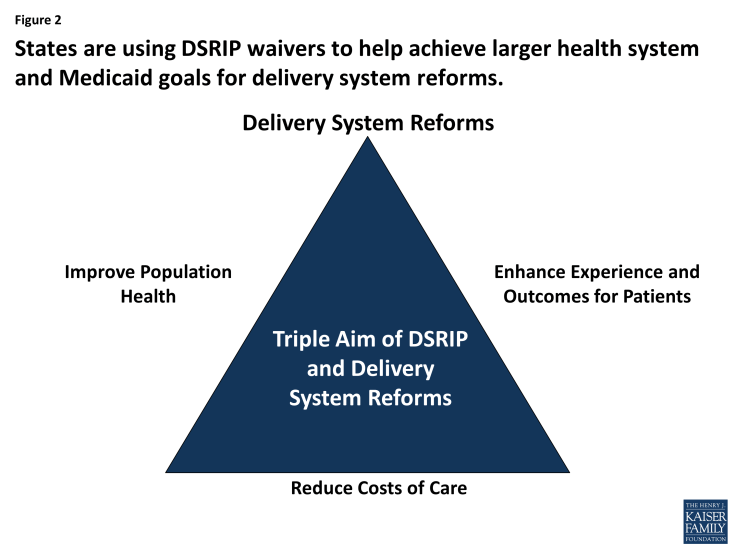

“Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment” or DSRIP programs are another piece of the dynamic and evolving Medicaid delivery system reform landscape. DSRIP initiatives are part of broader Section 1115 Waiver programs and provide states with significant funding that can be used to support hospitals and other providers in changing how they provide care to Medicaid beneficiaries. Originally, DSRIP initiatives were more narrowly focused on funding for safety net hospitals and often grew out of negotiations between states and HHS over the appropriate way to finance hospital care. Now, however, they increasingly are being used to promote a far more sweeping set of payment and delivery system reforms. The first DSRIP initiatives were approved and implemented in California and Texas in 2010 and 2011, followed by New Jersey, Kansas and Massachusetts in 2012 and 2013 and most recently New York which was approved in 2014 and will be implemented in 2015. At the highest level, DSRIP waivers are designed to advance the “Triple Aim” of improving the health of the population, enhancing the experience and outcomes of the patient and reducing the per capita cost of care (Figure 2).

Figure 2: States are using DSRIP waivers to help achieve larger health system and Medicaid goals for delivery system reforms

Section 1115 Medicaid waivers provide states with an avenue to test new approaches in Medicaid that differ from federal program rules. These waivers are intended to allow for “experimental, pilot, or demonstration projects” that, in the view of the HHS Secretary, “promote the objectives” of the Medicaid program. Section 1115 waivers have historically been used for a variety of purposes, including expanding coverage to populations who were not otherwise eligible, changing benefits packages, and instituting delivery system reforms. There is long-standing policy that requires 1115 Waivers to be budget neutral for federal spending meaning the federal government will not spend more with the waiver than if the waiver were not in place. Setting waiver policies and budget neutrality involve a lot of negotiations with states and the federal government.

There is no official federal guidance about what qualifies as a DSRIP program. Beyond the six mentioned above, a number of other states, including Florida, New Mexico, and Oregon, operate initiatives that share key elements of DSRIP waivers, but are not included as DSRIP waivers for purposes of this paper. With the prospect of hundreds of millions of dollars in federal Medicaid funding and the opportunity to promote a delivery system reform agenda, more states now are stepping forward to pursue DSRIP waivers. For example, Alabama, Illinois, and New Hampshire all are in various stages of developing DSRIP waivers.

Key Elements of DSRIP Waivers

This brief will examine similarities and differences across key elements of DSRIP waivers. The states included in this analysis are: California, Texas, Kansas, New Jersey, Massachusetts, and New York. As noted above, each of the DSRIP waivers were part of broader state reform waivers. For each of these states, Table 1 identifies the larger 1115 waiver into which the DSRIP initiative is folded, as well as the duration of the DSRIP component.

| Table 1: Timing and Authority for DSRIP Initiatives | ||

| State | Time Frame | Broader Waiver Authority |

| California | 2010-2015 | Bridge to Reform Waiver |

| Texas | 2012-2016 | Transformation and Quality Improvement Waiver |

| Massachusetts | 2011-2014 | MassHealth |

| New Jersey | 2014-2017 | Comprehensive Medicaid Waiver |

| Kansas | 2014-2017 | KanCare Waiver |

| New York | 2014-2019 | Medicaid Reform Transformation Waiver |

The key elements of DSRIP initiatives that will be explored in this analysis include: the goals and objectives of DSRIP initiatives; eligible providers; projects and organization; allocation of funds; data collection and evaluation/reporting; and financing of DSRIP waivers. As a group, the waivers share some common elements, but there also are differences across states due to state-specific circumstances as well as the evolution of these waivers over time.

Goals and Objectives

The overarching goal of all of the state DSRIP initiatives is transformation of the Medicaid payment and delivery system in an effort to achieve measureable improvements in quality of care and overall population health. The initiatives link funding for eligible providers to their progress toward meeting specific milestones. Individual states may have a range of reasons for pursuing DSRIP waivers that include delivery system reforms but may also include interest in maintaining or directing funds to hospitals or other providers.

Eligible Providers

Originally, DSRIP initiatives were narrowly focused on providing funds to safety net hospitals for delivery system reform. Over time, these waivers are increasingly being used to support a broader array of providers (hospital and non-hospital) in pursuing delivery system reforms. As such, a key choice for states is to decide which provider is eligible for DSRIP funds and, in particular, the role of non-hospital providers in DSRIP-funded initiatives. (Table 2)

| Table 2: Eligible Providers | |||

| State | Public Hospitals | Private Hospitals | Non-Hospital Providers |

| California | x | ||

| Texas | x | x | x |

| Massachusetts | x | x | |

| New Jersey | x | x | |

| Kansas | x | x | |

| New York | x | x | x |

As shown in Table 2, all states use their DSRIP waivers to fund public hospitals for delivery system reform, but a significant number also allow private hospitals to receive funding. To be eligible for funding, hospitals generally must meet standards for serving a certain proportion of Medicaid and uninsured populations. In many states, hospitals with larger Medicaid/uninsured populations are eligible to receive higher funding allocations. In addition, a state may require a hospital to make intergovernmental transfers as a condition of receiving DSRIP funds. The number of hospitals receiving DSRIP funding also varies across states. In Kansas, only two hospitals (The University of Kansas Hospital and Children’s Mercy Hospital) are eligible to participate in DSRIP, compared to 7 hospitals in Massachusetts, 21 hospital systems in California and 63 hospitals in New Jersey.

DSRIP waivers in Texas and New York require that funds be used for a broader set of providers, and these states are using their DSRIP waivers to promote collaborative provider networks that consist of an anchor hospital, associated clinics, and other providers or entities. In Texas, the state is broken up into 20 Regional Healthcare Partnerships (RHP). Each RHP is led by a public hospital or local governmental entity — such as a county or district hospital — that is responsible for funding the state match in partnership with regional health care providers. The larger provider network, however, can include community health centers, county health departments, and other non-hospital providers. Similar to Texas, New York is using its DSRIP waiver to promote coordinated networks of care organized around a lead hospital provider and component providers.

Projects and Organization

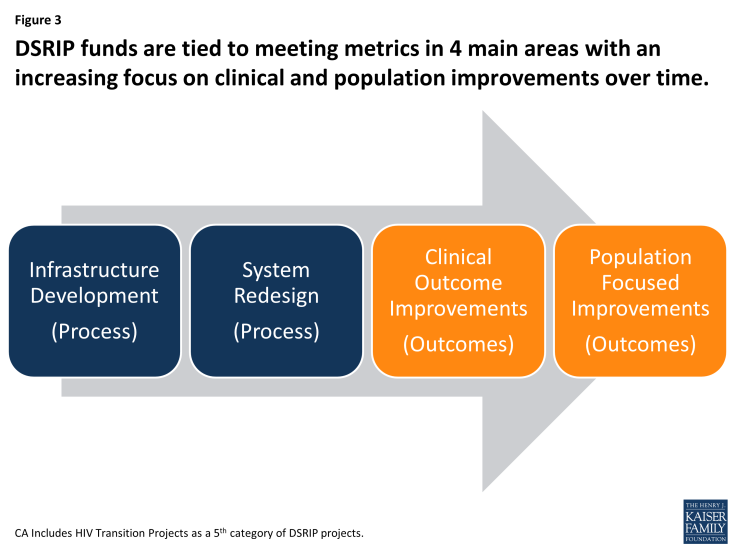

DSRIP allows Medicaid funding to be used to create incentives for providers to pursue key elements of delivery system reform. The details of what these key elements look like vary across states and waivers, but, generally include projects focused on the following four areas (although the terminology differs across states): infrastructure development, system redesign, clinical outcome improvements, and population focused improvements. In general, DSRIP waivers are set up to focus on achieving metrics and milestones in infrastructure and system redesign (more process oriented changes) in the earlier years of the waiver and then focus shifts toward reaching clinical and population focused metrics and milestones (more outcome based measures) in the later years of the waiver (Figure 3). States typically require eligible entities to submit a plan for approval that outlines the specific projects and metrics they intend to implement.

Figure 3: DSRIP funds are tied to meeting metrics in 4 main areas with an increasing focus on clinical and population improvements over time

DSRIP waivers vary in the rules and procedures governing the kinds of projects that can be undertaken for each of the major stages of delivery system reform. For example, eligible providers in California, Massachusetts and Texas generally had flexibility to choose specific projects and select the metrics for delivery system reform; while in New Jersey, Kansas, and New York, the state is more prescriptive about the specific projects and metrics from which eligible providers may choose. In Texas, eligible entities choose projects within 4 main focus areas laid out in broad parameters set by the state.

Process Metrics: Infrastructure Development and System Redesign Efforts

Infrastructure development projects are generally focused on investments in technology, tools and human resources that are needed to allow a hospital or network of providers to move forward with delivery system reform. System redesign projects focus on fostering new and innovative models of care delivery that expand access and improve quality.

For example, infrastructure projects could focus on developing training for the primary care workforce, or introducing telemedicine; implementing disease management or chronic care management registries/systems; and enhancing interpretation services and culturally competent care (including the collection of accurate Race, Ethnicity and Language (REAL) data).

System redesign projects may include the following: redesigning primary care models and expanding medical homes; establishing patient navigation programs; expanding chronic care management models and medication management programs; integrating physical and behavioral health care; and creating integrated delivery systems.

In New Jersey and Kansas, each project has an element of infrastructure development metrics and investments tied to it, such as staff training or the development of educational models. In New York, there is a set of core metrics related to operations or process measures that focus on approval of the DSRIP Plan, workforce milestones related to net change in providers, and system integration milestones. Eligible providers also must choose 2 system transformation projects.

Outcome Measures: Clinical Care and Population Health Improvements

Clinical care improvements and population focused improvements are tied to measurable outcomes and metrics to address patient care and safety, and improvements in overall health. Some states specify areas for clinical and population health improvement metrics, while others allow providers flexibility to determine the key areas for improvement as well as the metrics. There is significant overlap across states between these priority areas.

In California all DSRIP hospitals must make improvements on some key clinical outcomes, such as the rate of sepsis detection, the effectiveness of stroke management techniques, and the prevention of Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infection (CLABSI). Along with these standardized requirements, each DSRIP hospital must also select and report on their progress in improving outcomes for high burden conditions such as HIV/AIDS and asthma. In effect, the state is requiring hospitals to make improvements on a number of defined clinical outcomes, but also giving them some flexibility to identify other clinical areas where improvements are needed.

In New Jersey each project has defined outcome measures that are similar across projects, such as reduced admissions, reduced emergency department visits, improvements in care processes, and increases in patient satisfaction. However, each project may also have specific metrics which are primarily measured by NCQA, AMA Primary Care Incentive Program (PCIP), the Joint Commission, AHRQ, CMS or HRSA. For example, specific metrics for the project to improve cardiac care by reducing 30-day readmissions requires reporting and progress on several NCQA measures, such as controlling high blood pressure and compliance with post-discharge appointments.

In New York, each major network of providers (referred to as “Performing Provider Systems” or “PPSs”) must establish at least two priorities for clinical improvement. The state has set some parameters around what the PPSs can focus on by requiring that their goals achieve at least one of two things: tackle behavioral health issues and address HIV/AIDS, cardiovascular health, perinatal health, diabetes care, palliative care, asthma or renal care. In addition, each PPS must select one population-wide project that promotes mental health and prevents substance abuse; prevents chronic diseases; prevents HIV and STDs; or promotes healthy women, infants and children.

Statewide DSRIP Progress Measures

HHS efforts are underway to ensure that DSRIP waivers are translating into improvements in care across a state as a whole. To that end, the latest waiver approval for New York makes DSRIP funding to the state (not just funding to eligible providers) contingent upon the state meeting statewide metrics tied to the overall goal of reducing avoidable hospitalizations. Specifically, the state must meet statewide delivery system reform metrics, the majority of all specified individual project metrics must be met, growth in total Medicaid spending and spending on inpatient and ER services must fall at or below target trend rates, and the state must show demonstrated progress toward ensuring 90 percent of managed care payments are value-based by the end of the five year demonstration period. If any of these four milestones above are not met, then DSRIP payments to providers will be reduced proportionately across all DSRIP Performing Provider Systems based on the valuation of their DSRIP project plans.

Allocation of Funds

DSRIPs are not grant programs – they are performance-based incentive programs. In all states, providers must meet certain process or outcome measures to qualify for DSRIP funding; however, states vary in terms of the methodology for allocating the DSRIP funding across providers, demonstration years, and projects. Past DSRIP waivers have prioritized certain types of projects (e.g., integrated healthcare delivery, expanded primary care capacity, and/or population-focused improvements), as well as certain provider types (e.g., those with the largest percentages of Medicaid and uninsured patients). Generally, over the course of a state’s DSRIP initiative, funding allocations for meeting milestones related to clinical care and population health receive higher levels of funding.

In California, for example, the allocation of funds was based on specific provider plan submissions for infrastructure and system redesign, a formula for allocating payments for clinical care, and population improvements, which are required to comprise 20-30 percent of funding for demonstration year 5. Each intervention’s incentive payment amount will be determined using a formula where a base amount is multiplied by factors to determine the total dollars for that intervention. The amount of the incentive funding paid to a provider is based on the amount of progress made meeting milestones.

New Jersey bases fund allocation on achievement values (AVs) for early state metrics and performance and outcomes in later years. In New Jersey, amounts of the DSRIP pools will be set aside and directed to a Universal Performance Pool (UPP), which shall be available to hospitals that successfully maintain or improve a subset of DSRIP Performance Indicators.

In New York, DSRIP dollars will be allocated across two pools—one for public hospital-led PPS projects and one for all other hospital-led PPS projects. The maximum amount of funds for each PPS is based on set values for the projects chosen, the number of Medicaid enrollees attributed to the PPS, and the application scores each PPS receives on their State-submitted program plans. Within the DSRIP funding pool of $6.42 billion, New York has reserved $20 million1 for planning grants and $300 million for state administration as part of the DSRIP funding. New York will also allocate some DSRIP funds to create a performance pool available to providers that exceed the stated quality improvement goals. As mentioned earlier, in addition to the metrics and milestones applicable to each PPS project, New York must meet statewide performance goals to obtain full DSRIP funding. Beginning in year three of the demonstration, failure to achieve these goals can result in the state losing some of its DSRIP funding. 2

Data Collection and Evaluation / Reporting and Assessment

One of the primary features of DSRIP waivers is that funding is tied to meeting specific milestones. As a result, states must establish data collection and reporting requirements that adequately measure provider performance. Most DSRIP waivers are focused on process measures in the early years and then require more outcomes measures further into the demonstration. A number of states also include a mid-demonstration assessment that allows the state adjust its metrics and measures for the latter part of the demonstration.

Generally, across states, the hospitals or providers are required to submit semi-annual reports to the state detailing progress in meeting specified metrics or milestones. In addition, providers may also need to submit annual reports that also, for example, include narrative descriptions of progress made, lessons learned, and challenges faced. Moreover, states must provide extensive data to the federal government regularly to demonstrate that they are complying with the terms and conditions of their waivers, as well as meeting “budget neutrality” requirements (discussed below).

For example, New York specifies 6 types of reports and ongoing formal monitoring (beyond standard CMS 1115 oversight):

- Semi-annual reporting on project achievement (although some metrics are reported annually);

- Quarterly state monitoring reports on PPS progress and challenges;

- An operational report to track DSRIP performance, a consumer level report to report high-level geographic and project-specific data elements to understand which providers are driving improvement quality;

- Learning collaboratives to promote and support continuous learning and sharing environments based on data transparency within the NY healthcare industry;

- Program evaluation conducted by an independent evaluator to provide an interim and summative evaluation; and

- Overall data standards will be collected as often as is practical in order to ensure that project impact is being viewed in “real time.”

Financing of DSRIP

The financing of DSRIP initiatives approved to date is complex, largely because the cost of delivery system reform initiative payments must be folded into an 1115 waiver. As a result, the financing of DSRIP initiatives is tied to the financing of 1115 waivers, which often are being used by a state to accomplish multiple objectives at once. While these waivers specify an amount of federal funds available for DSRIP initiatives, the broader 1115 waiver must be budget neutral for federal spending, meaning spending under the waiver will not exceed predicted spending without the waiver. Some of the DSRIP initiatives originally were designed to help states retain federal Medicaid matching funds associated with supplemental payments to hospitals.

Federal Financing

The amount of Medicaid funding available to support DSRIP initiatives varies considerably across states, but can be substantial. For example, California, New York and Texas each expect to have several billion dollars (over $6 billion in California and New York and more than $11 billion in Texas) for their DSRIP initiatives over a five-year period (though the time period varies across states). Kansas, Massachusetts and New Jersey have smaller DSRIP initiatives with less spending. While the waivers include an amount of federal funding set aside for DSRIP initiatives, the entire waiver (including DSRIP) must meet budget neutrality requirements.

In the context of DSRIP waivers, it can be challenging to demonstrate budget neutrality. The cost of making payments to hospitals and other providers for broad-based delivery system reform is not an expense that the federal government would match in the absence of a Medicaid 1115 waiver. As a result, states must demonstrate that their 1115 waiver will generate “savings” (i.e., reduce the federal cost of operating Medicaid relative to the “without waiver” cost). They can then “tap” the expected savings and repurpose them for new investments in delivery system reform. To satisfy budget neutrality requirements, some states are redirecting federal Medicaid funds that they would have spent on supplemental payments to hospitals toward new delivery system reform payments. (These supplemental payments can include disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments or Upper Payment Limit (UPL) payments.)

In effect, states redirecting supplemental payments3 are repurposing these hospital-based payments and using them to finance delivery system reform incentives linked to performance measures. In Texas, the DSRIP initiative helped retain the ability to make significant supplemental payments to hospitals as it moved more aggressively toward the use of Medicaid managed care since federal regulations prohibit states from making certain supplemental payments to hospitals on behalf of Medicaid managed care beneficiaries. Texas was able to integrate these supplemental payments into the budget neutrality calculations underlying its Medicaid 1115 waiver, and, in effect, repurpose a significant share of them for delivery system reform.

State Financing

States remain obligated to pay for their share of the cost of DSRIP initiatives under Medicaid financing requirements. As such, they must identify a source of state dollars that can be used to “match” federal funding. States sometimes also use their spending on “Designated State Health Programs” or “DSHPs” as a source of state matching funds. DSHPs are health programs funded entirely by the state, many of which provide safety-net health care services for low-income or uninsured individuals such as adult day care, outpatient substance abuse treatment or care for the mentally ill who are not eligible for Medicaid. In the context of a larger 1115 waiver, states can sometimes secure federal Medicaid matching funds for the cost of such programs subject to approval from the federal government. States have then used the money that the state saves to finance the state share of DSRIP initiatives (or other 1115 waiver activities). In general, the federal government imposes strict limits on the extent to which it will provide federal Medicaid matching funds for DSHPs, making it an uncertain source of financing for future DSRIP waivers. States can also rely on a number of other financing options, including general revenue dollars or intergovernmental transfers (IGTs) from public hospitals and their sponsoring government entities to fund their DSRIP programs. Using the IGT approach, the public hospitals transfer local dollars to the state. The state then draws down federal funds to disburse to providers through the DSRIP program projects.

The dollar amounts involved with DSRIP waivers are substantial, but, by repurposing existing savings from 1115 demonstrations or Medicaid payments to hospitals, the waivers are estimated to be budget neutral for federal spending and give states and the federal government the tools for ensuring these funds are invested in delivery system reform.

Looking Ahead

DSRIP is one important element in the landscape of delivery system reform efforts that states are pursuing. CMS has not released specific guidance for states about requirements for DSRIP programs. However, more recent waiver approvals point to certain trends such as more accountability and the involvement of a broader set of providers. Additional states including Alabama, New Hampshire and Illinois are in various stages of developing DSRIP initiatives. Watching how states structure their programs in terms of eligible providers, projects and metrics as well as how they are financed and account for budget neutrality will provide additional guideposts for other states considering these programs. Other questions will be whether states can renew DSRIP waivers and how DSRIP programs might differ across states implementing the Medicaid expansion and those not implementing the expansion. Ultimately, it will be important to monitor these initiatives to measure success in meeting the goals of delivery system reform as well as achieving clinical and population health improvements. If these initiatives are successful, it will be important to see how these programs can be scaled and replicated across a larger number of states.

This brief was prepared by Alexandra Gates and Robin Rudowitz from the Kaiser Family Foundation and Jocelyn Guyer from Manatt Health. The authors would also like to thank Dori Glanz and Deborah Bachrach from Manatt Health for their help and review in preparing this brief.