A View from the States: Key Medicaid Policy Changes: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2019 and 2020

Provider Rates and Taxes

|

Key Section Findings |

| A strong economy and state revenue growth allowed most states to implement and plan more fee-for-service (FFS) provider rate increases for FY 2019 (50 states) and FY 2020 (45 states). This holds true across all provider types, including inpatient hospital rates and nursing facility rates. As more states increasingly rely on capitated managed care, however, FFS rate changes are a less meaningful measure of provider payment unless the state establishes MCO payment requirements. Nearly half of MCO states reported doing so: 19 states reported mandating minimum provider reimbursement rates in their MCO contracts for inpatient hospital, outpatient hospital, or primary care physicians and 17 states reported requiring MCOs to change provider payment rates in accordance with FFS payment rate changes for one or more of these provider types. As in prior years, data show that all states except Alaska rely on provider taxes and fees to fund a portion of the non-federal share of the costs of Medicaid. Six states indicate plans for new provider taxes in FY 2020.

What to watch:

Tables 12 through 14 provide complete listings of Medicaid provider rate changes and provider taxes and fees in place in FY 2019 and FY 2020. |

Provider Rates

Provider rate changes generally reflect broader economic conditions. During economic downturns and state revenue shortfalls, states often turn to rate restrictions to contain costs and are more likely to increase rates during periods of recovery and revenue growth. This report examines rate changes across major provider categories: inpatient hospitals, nursing facilities, MCOs, outpatient hospitals, primary care physicians, specialists, dentists, and home and community-based services (HCBS) providers. States were asked to report aggregate rate changes for each provider category in their fee-for-service (FFS) programs. States were also asked about aggregate rate increases for MCOs. Consistent with the strong economies prevailing in most states, more provider rate increases and fewer rate cuts were reported in FY 2019 and FY 2020.

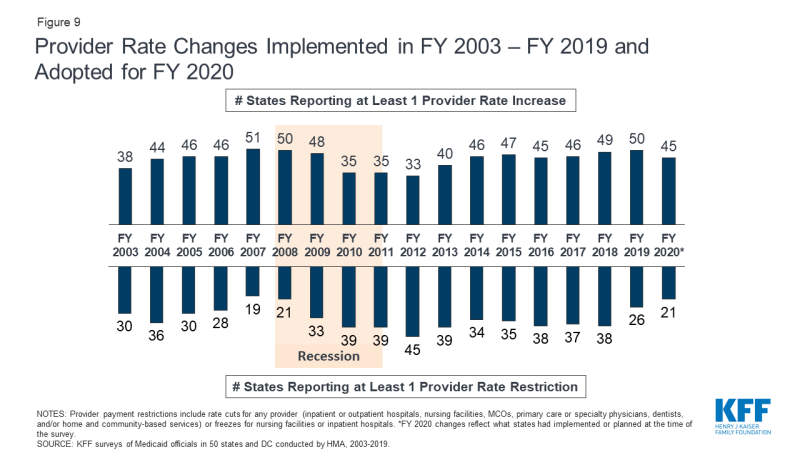

The number of states that made or are planning rate increases exceeds (for FFS and for MCOs) the number implementing or planning such rate restrictions in both FY 2019 and FY 2020. In FY 2019, almost every state implemented rate increases for at least one category of providers (50 states), while fewer states implemented rate restrictions (26 states) (Figure 9 and Table 12).1 For FY 2020, the number of states with at least one planned rate increase (45 states) is more than double the number of states with at least one planned rate restriction (21 states) (Figure 9 and Table 13). The number of states with planned rate restrictions is the lowest since FY 2008.

The number of states with rate increases exceeds the number of states with restrictions in FY 2019 and FY 2020 across all major categories of FFS providers and MCOs (Figure 10 and Tables 12 and 13). For the purposes of this report, cuts or freezes in rates for inpatient hospitals and nursing facilities are counted as restrictions.2 Almost all reported rate restrictions for inpatient hospitals and nursing facilities were rate freezes. One state, Alaska, indicated that it would have across-the-board 5% rate cuts in FY 2020 due to fiscal challenges. Nursing facilities received rate increases more often than other categories of providers. In both FY 2019 and 2020, 41 states indicated they have increased or plan to increase nursing facility rates. (In many cases, these increases reflect cost-of-living type adjustments.) HCBS providers were also among those most likely to receive rate increases (39 states in FY 2019 and 34 states in FY 2020) (Figure 10 and Tables 12 and 13).

State authority to adjust capitation payments for MCOs is limited by the federal requirement that states pay actuarially sound rates. In FY 2019 and FY 2020, most of the states with Medicaid MCOs (40 states in FY 2019 and 41 states in FY 2020) either implemented or planned increases in MCO rates. No states indicated MCO rate cuts for either FY 2019 or FY 2020.3

Requirements For mco payments to providers

As more states rely on capitated MCO arrangements, FFS provider rate changes are a less meaningful measure of provider payment, unless the state establishes MCO payment requirements. In this year’s survey, states were asked to report by provider category whether their MCO contracts establish minimum rates that the MCOs must pay providers and/or require MCOs to make provider payment changes that match uniform dollar or percent changes made in FFS.

Nearly half of MCO states (19 states) mandate minimum provider reimbursement rates in their MCO contracts for inpatient hospital, outpatient hospital, or primary care physicians (Exhibit 20). Of the 41 states with MCOs in FY 2020, 19 states indicated that they had rate floors in at least one of these three categories of acute care providers. Seven states reported “yes – for the entire category” for all three provider types. Some states indicated that they have rate floors for some but not all providers within a category.

| Exhibit 20: Mandated Minimum Rates MCOs Must Pay Selected Providers | ||||

| Rate Floor | Inpatient Hospital | Outpatient Hospital | Primary Care Physician | For Any Provider |

| Yes – for entire category | 10 | 8 | 7 | 12 |

| Varies – some providers in this category | 6 | 8 | 5 | 9 |

| Total with any minimum rate requirements | 16 | 16 | 12 | 19 |

| MD did not report. | ||||

Just under half of MCO states (17 states) require MCOs to change provider payment rates in accordance with FFS payment rate changes (uniform dollar or percent changes) for inpatient hospital, outpatient hospital, or primary care physicians (Exhibit 21). In many states, MCOs make most of the Medicaid payments to providers. This year’s survey asked states to report whether they require MCOs to make changes to provider payments that follow percent or level changes in FFS rates. Of the 41 states with MCOs in FY 2020, 17 states indicated that they had such a requirement for at least some providers in at least one acute care provider category (inpatient hospital, outpatient hospital, or primary care physician). Five states reported “yes – for the entire category” indicating they require MCOs to make these changes for all three types of providers.

| Exhibit 21: MCO Contracts Required to Match Uniform Changes Made in FFS | ||||

| Uniform Changes | Inpatient Hospital | Outpatient Hospital | Primary Care Physician | For Any Provider |

| Yes – for entire category | 9 | 7 | 6 | 10 |

| Varies – some providers in this category | 6 | 6 | 4 | 8 |

| Total with requirements to match changes in FFS | 15 | 13 | 10 | 17 |

| MD did not report. | ||||

RURAL Payment Adjustments

States were asked if they have payment adjustments in place to promote access to hospitals or other providers in rural areas — about half of states reported at least one policy to support rural providers. While there are federal reimbursement requirements for rural hospitals that meet the definition of a Critical Access Hospital, many states reported policies to promote hospital access in rural areas beyond these statutory requirements. For example, Washington plans to implement in FY 2020 performance-based payments for some Critical Access Hospitals in its Rural Health Access Preservation pilot to increase care coordination and access to care.

Other notable payment initiatives for rural hospitals include using a differential Diagnosis Related Group (DRG) price base, supplemental pools (sometimes through the distribution of Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments), use of state directed payments for inpatient or outpatient services, and higher reimbursement inflation factors. Some states noted special payment arrangements for Rural Health Centers in particular, and some states reported initiatives targeting other providers in rural areas, including the extension of telehealth services, higher payments for rural dentists, and investment in rural county personal care and rural nursing facilities.

While the focus of the survey question was on payment adjustments to rural providers, two states (Arizona and South Carolina) mentioned funding for rural graduate medical education designed to support the development of residencies and fellowships in rural medicine as a strategy for growth in rural and underserved communities. Tennessee noted a rural hospital initiative beyond payment policies: the state is working with targeted rural hospitals to transform their operations to become more sustainable. One state also noted that Medicaid managed care plans are required to maintain adequate provider panels to ensure access and may therefore choose to make differential payments to rural providers.

Pennsylvania’s Rural Health Model is an alternative payment model that will transition rural hospitals from FFS to global payments, with the goal of increasing rural Pennsylvanians’ access to high-quality care, improving their health, and reducing the growth of hospital expenditures across payers. The model will include Medicaid, but for 2019, five hospitals and five payers (Medicare and four health plans) are participating. The model was designed in partnership with the federal Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation.

Provider Taxes and Fees

Provider taxes are an integral source of Medicaid financing. At the beginning of FY 2003, 21 states had at least one provider tax in place. Over the next decade, most states imposed new taxes or fees and increased existing tax rates and fees to raise revenue to support Medicaid. By FY 2013, all but one state (Alaska) had at least one provider tax or fee in place.4

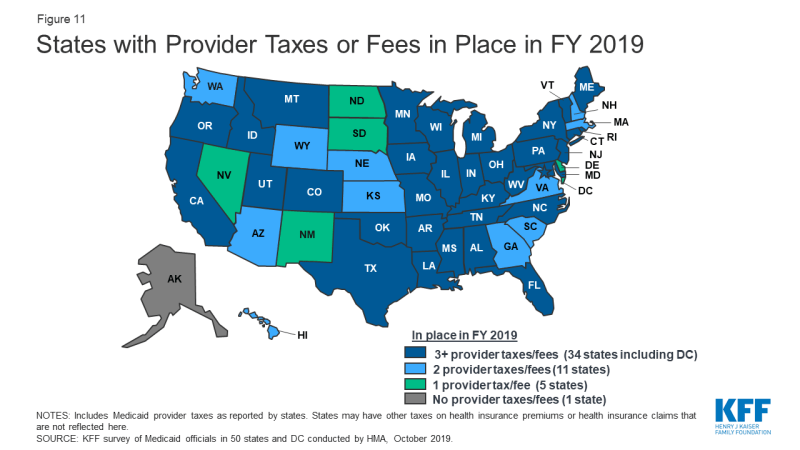

In this year’s survey, states reported continuing or increased reliance on provider taxes and fees to fund a portion of the non-federal share of Medicaid costs in FY 2019 and FY 2020. In FY 2019, 34 states, including DC, had three or more provider taxes in place (Figure 11).

Very few states made or are making any changes to their provider tax structure in FY 2019 or FY 2020 (Table 14). The most common Medicaid provider taxes in place in FY 2019 were taxes on nursing facilities (45 states), followed by taxes on hospitals (43 states) and intermediate care facilities for individuals with intellectual disabilities (ICF-IDs) (35 states). New Mexico plans to implement a tax on nursing facilities, bringing the total number of states with taxes on nursing facilities to 46 states in FY 2020, and a new hospital tax in Texas will increase the total number of states with a hospital tax to 44 states in FY 2020. Four other states reported plans to add new taxes in FY 2020. Three of these are new MCO taxes (Arkansas, California,5 and Illinois) and the fourth is a tax on hospital-based physicians (Wyoming).

Seventeen states reported planned increases to one or more provider taxes in FY 2020, while six states reported provider tax decreases. Thirty-two states reported at least one provider tax that is above 5.5% of net patient revenues, which is close to the maximum federal safe harbor threshold of 6%. Federal action to lower that threshold, as has been proposed in the past, would therefore have financial implications for many states.

Fourteen states report that they have taxes on MCOs as of FY 2019, and two additional states plan to implement new MCO taxes in FY 2020. Federal Medicaid law was changed effective July 1, 2009 to restrict the use of Medicaid provider taxes on managed care organizations such as HMOs.6 Prior to that date, states could apply a provider tax to Medicaid MCOs that did not apply to MCOs more broadly and could use that revenue to match Medicaid federal funds. In recent years, several states have implemented new MCO taxes that tax member months rather than premiums and that meet the federal statistical requirements for broad-based and uniform taxes. As a result, the number of MCO taxes has increased in recent years. In addition to the 16 states reporting implemented or planned MCO taxes, some states have implemented taxes on health insurers more broadly that generate revenue for their Medicaid programs.

An increasingly common provider tax is a tax on Ground Emergency Medical Transportation, or an ambulance tax. California implemented such a tax in FY 2019, bringing the number of states with an ambulance tax to eight states.

Table 12: Provider Rate Changes in all 50 States and DC, FY 2019

|

States |

Inpatient Hospital |

Outpatient Hospital |

Primary Care Physicians |

Specialists |

Dentists |

MCOs |

Nursing Facilities |

HCBS |

Any Provider |

|||||||||

|

Rate Change |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

|

Alabama |

X |

— |

— |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||

|

Alaska |

X |

X |

X |

X |

— |

— |

X |

X |

||||||||||

|

Arizona |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||

|

Arkansas |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||

|

California |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||

|

Colorado |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||

|

Connecticut |

X |

X |

X |

— |

— |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||

|

Delaware |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||

|

DC |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||

|

Florida |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||

|

Georgia |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||

|

Hawaii |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||

|

Idaho |

X |

X |

X |

X |

— |

— |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||

|

Illinois |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||

|

Indiana |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||

|

Iowa |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||

|

Kansas |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||

|

Kentucky |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||

|

Louisiana |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||

|

Maine |

X |

X |

— |

— |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||

|

Maryland |

X |

X |

X |

X |

NR |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||

|

Massachusetts |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||

|

Michigan |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||

|

Minnesota |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||

|

Mississippi |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||

|

Missouri |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||

|

Montana |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

— |

— |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||

|

Nebraska |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||||

|

Nevada |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||

|

New Hampshire |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||

|

New Jersey |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||

|

New Mexico |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||

|

New York |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||

|

North Carolina |

X |

X |

X |

— |

— |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||

|

North Dakota |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||

|

Ohio |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||

|

Oklahoma |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

— |

— |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||

|

Oregon |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||

|

Pennsylvania |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||

|

Rhode Island |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||

|

South Carolina |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||

|

South Dakota |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

— |

— |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||

|

Tennessee |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||||

|

Texas |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||

|

Utah |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||

|

Vermont |

X |

X |

X |

— |

— |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||

|

Virginia |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||

|

Washington |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||

|

West Virginia |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||

|

Wisconsin |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||

|

Wyoming |

X |

— |

— |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||

|

Totals |

27 |

24 |

28 |

3 |

20 |

0 |

14 |

1 |

14 |

2 |

36 |

0 |

41 |

10 |

39 |

0 |

50 |

26 |

|

NOTES: “+” refers to provider rate increases and “-” refers to provider rate restrictions. MCOs: Managed care organizations. HCBS: Home and community-based services. For the purposes of this report, provider rate restrictions include cuts to rates for physicians, dentists, outpatient hospitals, managed care organizations, HCBS, and pharmacy dispensing fees as well as both cuts or freezes in rates for inpatient hospitals and nursing facilities. There are 11 states that did not have Medicaid MCOs in operation in FY 2019; they are denoted as “–” in the MCO column. NR: State did not report. SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation Survey of Medicaid Officials in 50 states and DC conducted by Health Management Associates, October 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||

Table 13: Provider Rate Changes in all 50 States and DC, FY 2020

|

States |

Inpatient Hospital |

Outpatient Hospital |

Primary Care Physicians |

Specialists |

Dentists |

MCOs |

Nursing Facilities |

HCBS |

Any Provider |

|||||||||

|

Rate Change |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

|

Alabama |

X |

— |

— |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||

|

Alaska |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

— |

— |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||

|

Arizona |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||

|

Arkansas |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||

|

California |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||

|

Colorado |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||

|

Connecticut |

X |

X |

— |

— |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||

|

Delaware |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||

|

DC |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||

|

Florida |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||

|

Georgia |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||

|

Hawaii |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||

|

Idaho |

X |

X |

X |

X |

— |

— |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||

|

Illinois |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||

|

Indiana |

X |

NR |

NR |

NR |

X |

|||||||||||||

|

Iowa |

X |

X |

X |

X |

x |

X |

||||||||||||

|

Kansas |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||

|

Kentucky |

X |

X |

X |

X |

x |

X |

||||||||||||

|

Louisiana |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||

|

Maine |

X |

X |

— |

— |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||

|

Maryland |

X |

X |

NR |

NR |

NR |

NR |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||

|

Massachusetts |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||

|

Michigan |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||

|

Minnesota |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||

|

Mississippi |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||

|

Missouri |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||

|

Montana |

X |

X |

X |

X |

— |

— |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||

|

Nebraska |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||

|

Nevada |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||

|

New Hampshire |

TBD |

TBD |

TBD |

TBD |

TBD |

TBD |

TBD |

TBD |

||||||||||

|

New Jersey |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||

|

New Mexico |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||

|

New York |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||

|

North Carolina |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||

|

North Dakota |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||

|

Ohio |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||

|

Oklahoma |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

— |

— |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||

|

Oregon |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||||

|

Pennsylvania |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||

|

Rhode Island |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||

|

South Carolina |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||

|

South Dakota |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

— |

— |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||

|

Tennessee |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||||

|

Texas |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||

|

Utah |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||

|

Vermont |

X |

X |

X |

X |

— |

— |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||

|

Virginia |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||

|

Washington |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||

|

West Virginia |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||

|

Wisconsin |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||

|

Wyoming |

X |

— |

— |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||

|

Totals |

32 |

18 |

28 |

3 |

21 |

1 |

22 |

1 |

21 |

1 |

36 |

0 |

41 |

8 |

34 |

2 |

45 |

21 |

|

NOTES: “+” refers to provider rate increases and “-” refers to provider rate restrictions. MCOs: Managed care organizations. HCBS: Home and community-based services. For the purposes of this report, provider rate restrictions include cuts to rates for physicians, dentists, outpatient hospitals, managed care organizations, HCBS, and pharmacy dispensing fees as well as both cuts or freezes in rates for inpatient hospitals and nursing facilities. There are 10 states that did not have Medicaid MCOs in operation in FY 2020; they are denoted as “–” in the MCO column. NR: State did not report. SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation Survey of Medicaid Officials in 50 states and DC conducted by Health Management Associates, October 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||

Table 14: Provider Taxes in Place in all 50 States and DC, FY 2019 and FY 2020

|

States |

Hospitals |

Intermediate Care Facilities |

Nursing Facilities |

Other |

||||

|

2019 |

2020 |

2019 |

2020 |

2019 |

2020 |

2019 |

2020 |

|

|

Alabama |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

Alaska |

||||||||

|

Arizona |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

Arkansas |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

California |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X* |

|

Colorado |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

Connecticut |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Delaware |

X |

X |

||||||

|

DC |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Florida |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

Georgia |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

Hawaii |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

Idaho |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

Illinois |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Indiana |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

Iowa |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

Kansas |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

Kentucky |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X* |

X* |

|

Louisiana |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X* |

X* |

|

Maine |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Maryland |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Massachusetts |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

Michigan |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X* |

X* |

||

|

Minnesota |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X* |

X* |

|

Mississippi |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Missouri |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X* |

X* |

|

Montana |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

Nebraska |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

Nevada |

X |

X |

||||||

|

New Hampshire |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

New Jersey |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X* |

X* |

|

New Mexico |

X |

X |

X |

|||||

|

New York |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X* |

X* |

|

North Carolina |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

North Dakota |

X |

X |

||||||

|

Ohio |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Oklahoma |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

Oregon |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

Pennsylvania |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X* |

X* |

|

Rhode Island |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

South Carolina |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

South Dakota |

X |

X |

||||||

|

Tennessee |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X* |

X* |

|

Texas |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Utah |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Vermont |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X* |

X* |

|

Virginia |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

Washington |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

West Virginia |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X* |

X* |

|

Wisconsin |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

Wyoming |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||

|

Totals |

43 |

44 |

35 |

35 |

45 |

46 |

24 |

27 |

|

NOTES: This table includes Medicaid provider taxes as reported by states. Some states also have premium or claims taxes that apply to managed care organizations and other insurers. Since this type of tax is not considered a provider tax by CMS, these taxes are not counted as provider taxes in this report. “*” has been used to denote states with multiple “other” provider taxes. SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation Survey of Medicaid Officials in 50 states and DC conducted by Health Management Associates, October 2019 |

||||||||