A Profile of Community Health Center Patients: Implications for Policy

Use of Care

Health centers’ mission is to provide comprehensive primary care to their patients. Preventive health services and care management for ongoing health conditions are core components of this care, and several of the metrics used to evaluate health center quality focus on such services. Other research has demonstrated that health centers perform comparably to, if not better than, private practice physicians and other primary care providers in these spheres of care.1 This analysis, which complements that research, finds that, on key measures of preventive care and care management, health center users fare better than the low-income population in general. As with the results on health status, comparisons of utilization between health center patients and the low-income population overall may partly reflect the fact that health center patients are, by definition, already receiving care. However, even accounting for this difference, the analysis indicates some areas for concern regarding health center patients’ ability to access follow-up services, which may be outside the scope of services available at most health centers and thus require referrals. Because so many health center patients are uninsured, health centers face particular challenges in obtaining referrals.

Preventive Care

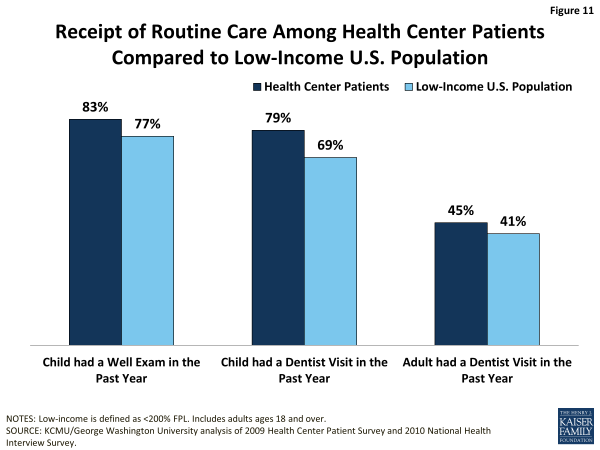

Well-child visits. On the most basic measure of preventive care for children—whether a child had a check-up within the past year—the data show that children who were health center patients fared better than children in the broader low-income population (Figure 11). This difference could reflect several underlying causes: patients who visit health centers may be more engaged in their care and thus more likely to visit a doctor for well-visits; health centers may do a better job of bringing patients in for routine care; or patients not seeking care at a health center may encounter barriers to well-child visits.

Dental visit. Health center patients are at least as likely as the general low-income population to report having had a dental visit in the past year (Figure 11). The share of adults with a dental visit is similar between the two populations. The fact that, in both groups, fewer than half received a visit warrants concern given the importance of good oral health to good overall health. The low visit rate likely reflects the high uninsured rate among low-income adults as well as very limited Medicaid coverage of adult dental benefits and low dentist participation in Medicaid. The low proportion of adult health center patients with a dental visit may also reflect the fact that, while dental care has been a priority expansion service for health centers, as of 2011, only 78% of all health centers reported offering dental care.2 Dental visit rates are higher among children, likely because of Medicaid’s comprehensive benefit package for children, known as EPSDT, which includes oral health services. Notably, children who are health center patients are more likely than low-income children overall to report a dental visit in the past year (79% vs. 69%). It is possible that children who receive at least some care in health centers are more connected to the health care system generally (including dental care), compared to all low-income children, or that they have better access to dental care through health centers compared to children who do not use health centers. The extent to which health centers that offer dental care focus on pediatric oral health also may be a factor.

Considering that health center patients are more likely to be uninsured than low-income people overall, it is interesting that they appear at least as likely to secure a dental visit. This finding may reflect the fact that, as mentioned earlier, most health centers offer dental care. At the same time, given that it is not possible to know whether the care received was preventive in nature or treatment for a dental problem, this finding is difficult to interpret. It could indicate a stronger connection to the health care system among health center users compared to low-income people overall, the availability of dental services in most health centers, and/or higher rates of oral disease among health center patients.

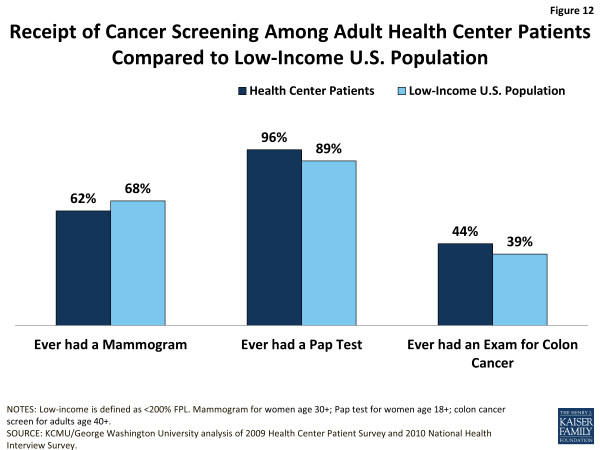

Cancer screening. Adult health center patients are at least as likely as low-income adults overall to report ever having received a Pap test (women only) or an exam for colon cancer, but appear slightly less likely to report ever having received a mammogram (women only) (Figure 12).

Follow-up and Chronic Care

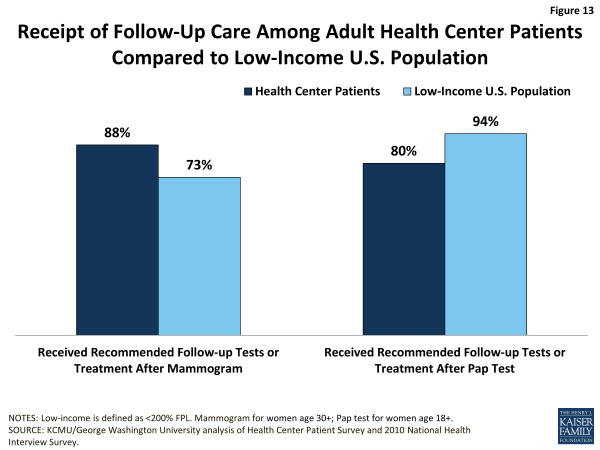

Follow-up cancer care. In addition to check-ups and screenings, referral for follow-up services and ongoing management of chronic illnesses are core components of comprehensive care. The findings on health center patients’ access to follow-up cancer tests are mixed and caution is required in interpreting them.

Although female health center patients are slightly less likely than all low-income women to report ever having received a mammogram, those who did have a mammogram and were referred for follow-up care are more likely (88% versus 73%) to have reported receiving the recommended follow-up care (Figure 13). At the same time, although they are slightly more likely than low-income women overall to report ever having received a Pap test, health center patients who did receive a Pap test are markedly less likely to report that they received the recommended follow-up care. Because health centers’ capacity to provide or arrange for specialist care, including cancer treatment, is very limited, measures of receipt of recommended follow-up cancer care by health center patients may reflect more about the issue of low-income people’s access to specialty care broadly, than about health centers or health center patients in particular. At the same time, a separate study of family planning services at health centers (which include Pap tests) suggests that health centers may focus less on providing this cancer screening service than other family planning services.3 Differences in follow-up care between health center patients and all low-income people may also stem from insurance differences between the two groups that affect their access.

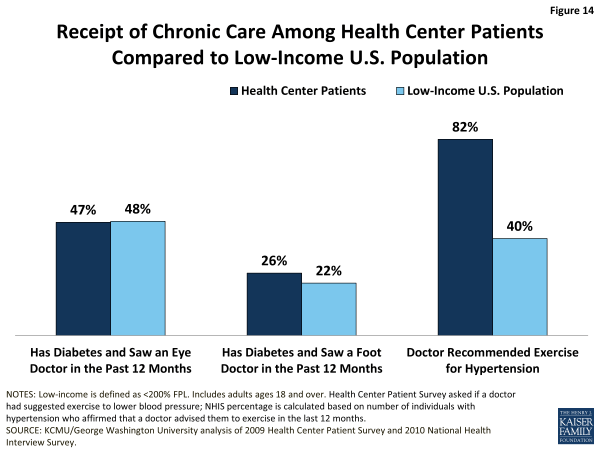

Chronic care. Among adults with diabetes, health center patients and all low-income adults report relatively similar rates of receipt of care to manage their diabetes. Roughly half of both populations report having seen an eye doctor in the past 12 months, and about one-quarter report having seen a foot doctor (Figure 14). As with cancer care, the follow-up eye and foot care described here is specialty care that health centers generally do not offer; thus, these measures, too, are indicators of access to specialty care among low-income people, rather than of health center performance or effectiveness.

Adult health center patients with hypertension are more than twice as likely as all low-income adults with hypertension to report that a doctor recommended exercise for them (82% vs. 40%). Some of this difference may reflect methodological differences in how the rates for the two groups are determined. The rate for health center patients is based directly on the Health Center Patient Survey question that asks respondents if a doctor suggested exercise to lower their blood pressure. The rate for low-income adults was derived as the share of NHIS respondents with hypertension who affirmed that their doctor advised them to exercise in the last 12 months. As distinct from the other two measure of chronic care, which require access to specialists, a recommendation to exercise is squarely within health centers’ preventive and primary care capacity. The higher rate of receipt of this intervention for hypertension among health center patients compared to low-income adults overall suggests that health centers are playing an important role in fostering patient self-management of this prevalent chronic condition.