A Primer on Medicare: Key Facts About the Medicare Program and the People it Covers

What is Medicare Advantage?

Medicare Advantage, also known as Medicare Part C, is a program that allows beneficiaries to enroll in private health plans to receive Medicare-covered benefits.

Private plans, such as health maintenance organizations (HMOs), have been an option under Medicare since the 1970s. Medicare now contracts with other types of private plans, including local preferred provider organizations (PPOs), regional PPOs, private fee-for-service (PFFS) plans, and high deductible plans linked to medical savings accounts (MSAs). In 2015, Medicare beneficiaries are able to choose from an average of 18 Medicare Advantage plans offered in their area.1

Medicare Advantage plans provide all benefits covered under traditional Medicare, and many plans offer additional benefits. The majority of plans also provide Part D prescription drug coverage.

Medicare Advantage plans receive payments from the federal government to provide all Medicare-covered benefits to enrollees. Plan sponsors are generally required to offer at least one plan with basic drug coverage. More than 8 in 10 Medicare Advantage plans (86 percent) offer drug coverage in 2015, and about four in ten plans (44 percent) offer some coverage beyond the standard benefit design in the coverage gap, mainly for generic drugs only. Plans are required to use any additional payments (known as rebates) to provide extra benefits to enrollees in the form of lower premiums, lower cost sharing, or benefits and services not covered by traditional Medicare. Examples of extra benefits include eyeglasses, hearing exams, preventive dental care, podiatry, chiropractic services, and gym memberships.

Medicare Advantage plan premiums and cost-sharing requirements vary widely, and have increased in recent years.

Medicare Advantage enrollees generally pay the monthly Part B premium and many also pay an additional premium directly to their plan. In 2015, the average premium for MA-PD plans (weighted by 2014 enrollment) is $41 per month, but varies by plan type and is lower for HMOs ($32) than for local PPOs ($70).2 Medicare Advantage plans are required to place a limit on beneficiaries’ out-of-pocket expenses for Medicare Part A and B covered services of $6,700 in 2015. In 2015, 9 percent of all Medicare Advantage plans have a limit of $3,400 or less, while almost half (48 percent) have a limit of more than $5,000.

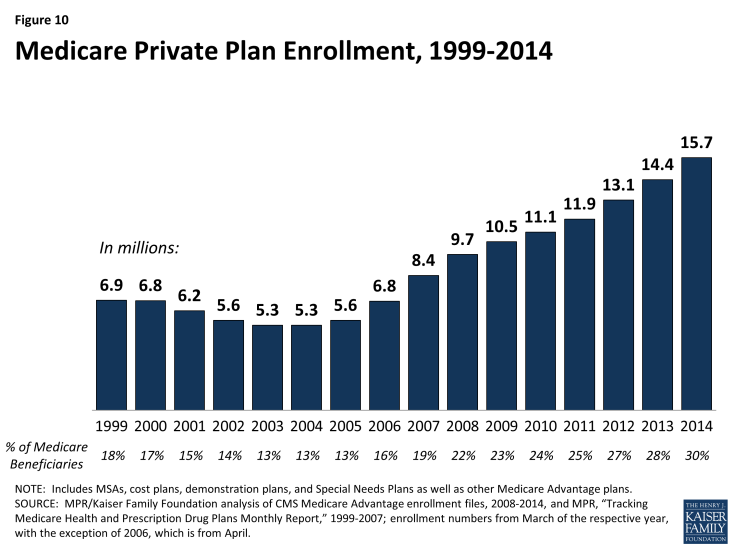

Since 2004, the number of Medicare Advantage plan enrollees has increased.

After a decline in the number of Medicare Advantage enrollees between 1999 and 2003, the program has seen a rapid increase in enrollment in more recent years (Figure 10). The number of Medicare enrollees in private plans has almost tripled between 2003 and 2014, from 5.3 million to 15.7 million. In 2014, 64 percent of Medicare Advantage enrollees were in HMOs, 23 percent were in local PPOs, 2 percent were in PFFS plans, 8 percent were in regional PPOs, and the remainder were in other plan types.3

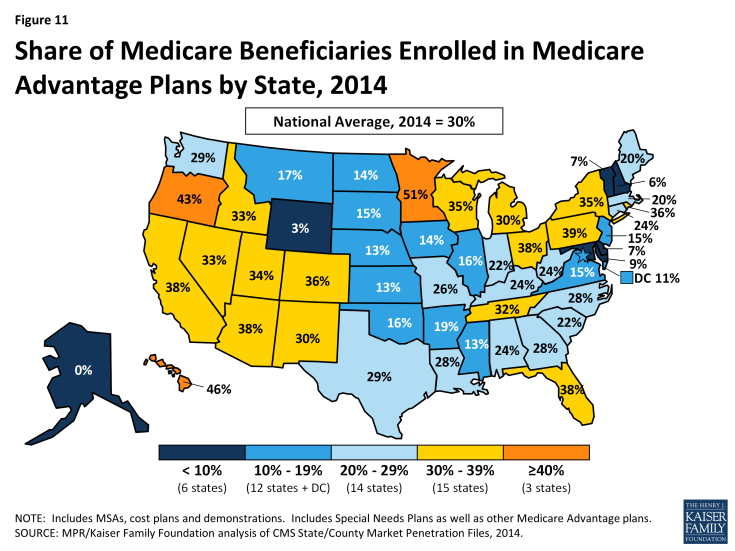

Enrollment in Medicare Advantage plans varies widely across states.

In 2015, less than 5 percent of beneficiaries in 2 states (Alaska and Wyoming) were enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans, while more than 30 percent of beneficiaries in 18 states (Arizona, California, Colorado, Florida, Hawaii, Idaho, Michigan, Minnesota, Nevada, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Utah, and Wisconsin) were in such plans (Figure 11).

The Affordable Care Act reduced Medicare payments to private plans and rewards plans with high-quality ratings.

Since 2006, Medicare has paid private plans under a bidding process: plans submit bids that estimate their costs per enrollee for services covered under Medicare Parts A and B. If plans bid higher than the county-level benchmark, enrollees pay the difference in the form of monthly premiums. If plans bid lower than the benchmark, the plan and Medicare split the difference between the bid and the benchmark; the plan’s share is known as a “rebate,” which must be used to provide supplemental benefits to enrollees. Medicare payments to plans are then adjusted based on enrollees’ risk profiles.

In the early-2000s, Medicare payment policy for plans changed from one that produced savings to one that focused more on expanding access to private plans and providing extra benefits to enrollees. Between 2006 and 2010, many advocates, policymakers, and researchers voiced concerns about rising “overpayments” to Medicare Advantage plans – estimated to be as much as 14 percent higher than what it would have cost to cover similar people in traditional Medicare.4 In response, the ACA reduce federal payments to Medicare Advantage plans over time, bringing them closer to the average costs of care under the traditional Medicare program. Under this payment system, plans in counties with relatively high traditional Medicare costs will be paid 95 percent of fee-for-service (FFS) costs per enrollee, while plans in counties with relatively low traditional Medicare costs will be paid 115 percent of FFS costs per enrollee. The ACA also provided bonus payments to Medicare Advantage plans based on the plan quality ratings, beginning in 2012. In addition, the ACA required Medicare Advantage plans to maintain a medical loss ratio no lower than 85 percent, restricting the share of premiums and other revenues that could be used for profits and administrative expenses.

Many questions remain to be answered about the quality of care and access to care in Medicare Advantage compared to traditional Medicare.

While many studies have examined the quality and access to care in Medicare Advantage plans, shortcomings in the available research make it hard to draw broad conclusions about the relative performance of the two coverage options.5 A systematic review found that the data used in studies that compare traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage tend to be old and provide limited information about the experience since the ACA was passed. Despite these limitations, at least through 2009, Medicare HMOs tend to perform better than traditional Medicare in providing preventive services and using resources more conservatively. Yet, beneficiaries rate traditional Medicare more favorably than Medicare Advantage plans in terms of quality and access, particularly sicker beneficiaries. Performance also has been found to vary widely across Medicare Advantage plans even within the same type.