Policy Options to Sustain Medicare for the Future

Section 5: Medicare Program Administration

Spending Caps

Options Reviewed

This section reviews the following options:

» Reduce the long-term target growth rate for Independent Payment Advisory Board (IPAB) recommendations from GDP+1% to GDP+0.5%

» Introduce a hard cap on Medicare per capita spending growth tied to the GDP per capita growth rate

» Introduce a hard cap on the total Federal health care spending per capita growth rate tied to the GDP per capita growth rate

Placing a limit on Medicare spending growth is one response to concerns about increases in Medicare spending and rising health care costs. Several provisions in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) have had the effect of reducing the projected Medicare spending growth rate over the next decade compared to past growth. On a per person basis, Medicare spending is projected to grow at a slower rate than private health insurance spending and considerably slower than historical growth in Medicare spending. Although there is concern that the program may be unable to sustain such low per capita growth rates over the long term, there also are concerted efforts around the delivery system and payment reforms designed to help control spending growth that were set in motion by the ACA. Recent data indicate historically low or flat growth in volume, which some observers attribute to the recent economic downturn, while others suggest that recent efforts to reform the delivery of care may also be taking hold (White and Ginsburg 2012).

Nevertheless, with Medicare enrollment projected to increase by 70 percent over the next 25 years and with projected increases in health care costs affecting Medicare as it does other payers, total Medicare spending is projected to increase at an annual rate of 5.6 percent over the next decade, considerably faster than the growth in per capita spending and the projected growth in the economy, and thus represents a growing share of the economy, the Federal budget, and the nation’s total health spending.

This section examines policy options related to imposing a cap on the Medicare per capita spending growth rate, beginning with a discussion of how current law incorporates spending limits and budget enforcement mechanisms within Medicare and of various design elements related to proposed spending limits. It describes three options to constrain per capita Medicare spending, using the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita growth rate as a benchmark for Medicare per capita spending growth. This section does not include options to place a system-wide cap on total U.S. health care spending growth, which would involve broader approaches and constraints on spending by public and private entities that are beyond the scope of this report. This section also does not address specific payment mechanisms that establish some form of spending limit within traditional Medicare, such as bundled payments or global budgets. For a discussion of these options, see Section Two, Provider Payments.

Background

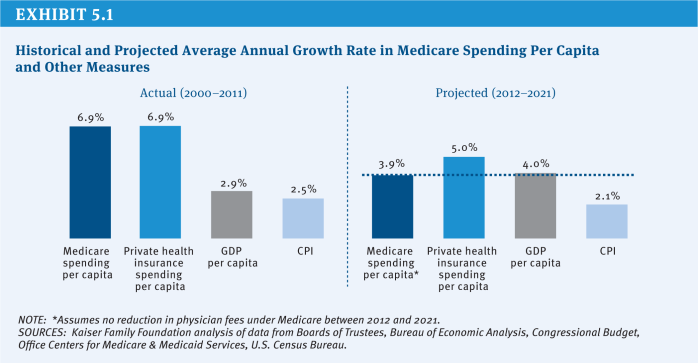

Health care costs—including Medicare costs—historically have grown faster than the U.S. economy. Between 2000 and 2011, for example, Medicare per capita spending grew at an annual rate of 6.9 percent, compared with a 2.9 percent annual growth in gross domestic product (GDP) per capita. Since enacting Medicare in 1965, Congress frequently has acted to curb Medicare spending through a series of laws that revised provider payment rates and systems, increased beneficiary cost sharing, or raised revenues through changes in tax law. These changes have, at times, slowed annual Medicare spending growth and extended the solvency of the Medicare Part A Trust Fund. Some of these savings have, however, proved to be more short-term in nature and the upward curve of Medicare spending growth has remained relatively steady.

As part of the ACA, Congress enacted $716 billion in 10-year Medicare savings (2013–2022), reducing the projected Medicare per capita spending growth rate to historically low levels. Between 2012 and 2021, average annual Medicare spending per beneficiary is projected to grow by 3.9 percent, less than the projected growth in per capita private health insurance spending (5.0 percent) and about the same as per capita GDP growth (4.0 percent) (Kaiser Family Foundation 2012b) [exhibit 5.1].

Current law incorporates several limits on Medicare spending and mechanisms to trigger spending reductions if spending exceeds certain targets. These are:

» The Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR), enacted as part of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, is used in determining annual updates to Medicare physician payments based, in part, on the estimated 10-year average annual growth in real GDP per capita (among other factors). Based on this calculation, if actual spending exceeds the SGR target, the next annual physician payment update is reduced; conversely, if spending is lower than the target, the update is increased. Strict adherence to the SGR formula would have resulted in significant cuts in Medicare physician payment rates but Congress has acted several times to override those reductions.

» The Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 added a “Medicare solvency trigger” requiring the Medicare Board of Trustees to annually report whether general revenues are projected to finance 45 percent or more of Medicare spending in any of the next seven years. If so, the Trustees are required to issue a “Medicare funding warning.” In response, the President is to submit legislation and Congress is to consider this legislation on an expedited basis. Such a warning has been issued each year since 2006 but no legislation has been specifically enacted to address it. During the 111th Congress, the House of Representatives passed a resolution to disregard any such funding warning issued by the Board of Trustees; the resolution was not in effect for the 112th Congress.

» The Affordable Care Act established an Independent Payment Advisory Board (IPAB). Beginning in 2015, if the projected five-year average growth rate in Medicare per beneficiary spending exceeds a per capita target growth rate, based on general and medical inflation (2015–2019) or GDP (2020 and beyond) IPAB is required to make recommendations on how to reduce growth. The ACA imposed limits on how much of a reduction IPAB can recommend and a prescribed time period for statutory review and revision. For the 113th Congress, the House of Representatives has passed a rule to disregard the fast-track procedures established for considering IPAB recommendations.

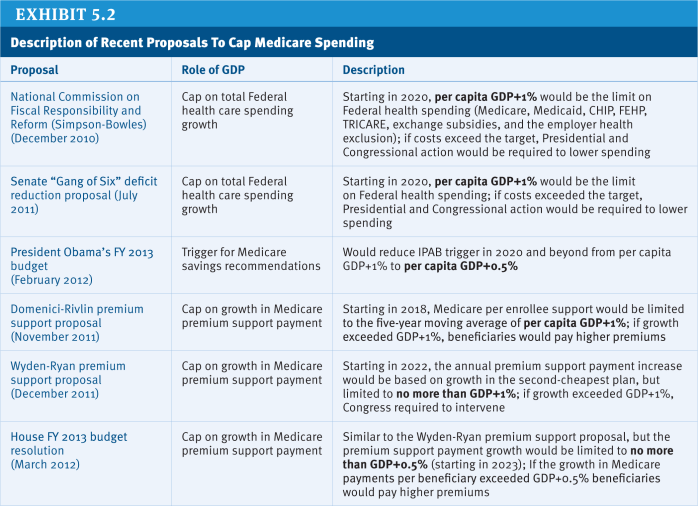

Yet even with the various constraints on Medicare spending imposed under current law, total Medicare spending is projected to rise from 3.1 percent of GDP in 2012 to 5 percent in 2037 (CBO 2012). Imposing a budget cap on Medicare spending could achieve greater budget certainty and more control over future growth in program spending. The specific approaches that have been suggested for limiting Medicare spending growth differ along several important dimensions [exhibit 5.2]:

» What benchmark is used as the spending target? Different benchmarks can be used as the measure to which the Medicare spending growth rate is compared. The most commonly discussed benchmarks include GDP (a measure of national economic output) and the Consumer Price Index (CPI, a measure of overall inflation). These benchmarks can be measured overall or on a per capita basis, which would adjust for population size and growth. In most proposals, the limit is based on the annual per capita rate of growth in GDP plus one percentage point or 0.5 percentage points (GDP+1%; GDP+0.5%).

» Is the limit is a “hard” or “soft” cap? Different approaches to enforcement include whether the spending limit is “hard” or “soft.” Both the Medicare solvency trigger and IPAB are examples of “soft” caps because they require additional action to achieve any savings. IPAB’s target growth rate itself is not a cap on annual Medicare spending growth, but rather a benchmark that triggers whether Medicare spending reductions are needed. In contrast, for “hard cap” approaches, a benchmark growth rate is used as an actual limit on Medicare spending growth. An example of a hard cap appeared in the Fiscal Year 2013 House Budget Resolution, which included a cap on Medicare per capita spending growth of GDP+0.5% as part of a proposal to transform Medicare to a premium support system (House Budget Committee 2012).

» How would savings be achieved if spending exceeded the cap? Whatever process is established for decision-making about spending reductions, the main question then is where the spending reductions would be made. For example, would the burden fall on providers in the form of payment reductions, on plans in the form of restrictions on premium increases, on beneficiaries in the form of increases in cost sharing or premiums, on taxpayers in the form of higher taxes or other new revenues, or on other areas of the Federal budget? In addition to specifying the actions that would be required, protections could be established to prevent spending reductions from directly affecting some or all beneficiaries or certain types of providers. Under current law, for example, IPAB is prohibited from recommending changes that would restrict benefits or eligibility, increase cost sharing or premiums, ration care, or (for a period of time) reduce payments for certain providers.

» What entity determines whether the cap has been exceeded and what actions would be taken as a result? Decisions also are needed about what action(s) would be taken and by whom if the limit is exceeded. For example, would the Executive Branch submit proposed changes to Congress for approval? Would Congress be charged with developing a legislative response, or would this authority be delegated to some other group or agency (such as an independent board like IPAB)? In the case of IPAB, the chief actuary of CMS is responsible for calculating the Medicare spending growth rate and the target growth rates against which Medicare spending growth is measured, while the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) is required to submit recommendations to Congress if IPAB fails to do so by the date specified in the law, and is authorized to carry out the Board’s recommendations if Congress fails to act in the required timeframe, or an alternative that has been enacted (Kaiser Family Foundation 2011).

Alternatively, the response could be taken out of the hands of elected officials altogether, through such mechanisms as automatic sequestration or automatic revenue increases. However, there is nothing that can prevent Congress from stepping in at any time to revise any targets or caps or mitigate the potential effects of enforcement of a target or cap that has been exceeded.

For any of these approaches, other important questions are the time period over which Medicare spending and the target growth rate would be evaluated (e.g., using a five-year period over which an average annual rate of growth is calculated), and the entity (or entities) in charge of calculating the Medicare spending limit (OMB, CBO, or another independent authority).

Policy Options

Several options proposed recently incorporate some measure for limiting Medicare spending growth or triggering Medicare spending growth reductions. Three options are discussed.

OPTION 5.1

Reduce the long-term target growth rate for Independent Payment Advisory Board (IPAB) recommendations from GDP+1% to GDP+0.5%

President Obama’s Fiscal Year (FY) 2013 budget proposal included a provision to reduce the Medicare savings trigger in the IPAB process in 2020 and beyond from GDP+1% to GDP+0.5%, thereby setting a lower bar for measuring whether savings would be needed. (Some have also proposed lifting the restrictions on what IPAB can recommend and allowing the IPAB to make recommendations to reduce total Federal health spending, not just Medicare spending; for a more detailed discussion of these ideas, see Section Five, Governance and Management).

Budget effects

The President’s FY 2013 budget did not separately score any savings in the 10-year budget window for the proposal to revise the IPAB target growth rate for Medicare, and CBO did not separately score this proposal. However, CBO has projected, based on current projections, that IPAB will not be required to make savings recommendations in the coming decade because Medicare spending is not projected to exceed the GDP+1% target. Lowering the GDP growth rate target to GDP+0.5% could mean that IPAB would need to make Medicare savings recommendations sooner.

Discussion

The proposal to lower IPAB’s target growth rate and the IPAB process in general, are driven by a budgetary concern about growth in Medicare spending—in particular over the long term. One concern with this approach is identifying the “right” growth rate to strive for to constrain Medicare spending growth without falling too far below marketplace trends in payment and potentially jeopardizing beneficiary access to providers.

The way that the GDP growth rate is incorporated into the IPAB process may be a more measured approach toward the goal of setting some kind of limit on Medicare spending growth than “hard cap” options. In the IPAB process, the target growth rate of GDP+1% (or GDP+0.5% under this option) is not a fixed cap on Medicare spending. Instead, if Medicare spending growth exceeds the target growth rate, the Board’s recommendations must achieve savings totaling the lesser of either: 1) the amount by which projected spending exceeds the target (expressed as a percent of projected Medicare spending), or 2) total projected Medicare spending for the year multiplied by 0.5 percent in 2015, 1.0 percent in 2016, 1.25 percent in 2017, and 1.5 percent in 2018 and beyond. Therefore, regardless of the magnitude of the average annual growth rate of Medicare or how different from the GDP growth rate, any spending reduction triggered by IPAB can never exceed a maximum of 1.5 percent of projected Medicare spending after 2018.

The statutory limits on IPAB recommendations also limit its purview to spending reductions in payments to providers and plans (with some exceptions on the providers subject to reductions prior to 2020). It is uncertain whether IPAB may address other aspects of payment beyond plan and provider payment rates, and the law does not specify what other proposals IPAB could recommend to achieve savings beyond payment reductions. Some have expressed concern that deep provider spending reductions could have an indirect effect on beneficiaries’ access to care, but the current law is clear in prohibiting measures that would more directly target beneficiaries in terms of cutting benefits or increasing out-of-pocket spending to achieve the required savings. (For a discussion of additional issues related to the role, structure, and scope of IPAB, see Section Five, Governance and Management.)

OPTION 5.2

Introduce a hard cap on Medicare per capita spending growth tied to the GDP per capita growth rate

Some recent proposals would place a “hard” cap on the Medicare per capita spending growth rate at the rate of growth in GDP plus a specified percentage point (GDP+1% or GDP+0.5%). A similar approach is included in several premium support proposals, where a benchmark is used to set a fixed limit on the annual growth in the government’s premium support payment for Medicare beneficiaries, but proposals differ in terms of the specific growth rate that would be used, as well as along several other dimensions (Kaiser Family Foundation 2012a). For a discussion of premium support proposals, see Section Four, Premium Support.

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option. A hard cap could be calibrated to achieve whatever Federal savings were desired.

Discussion

Setting a fixed limit on annual Medicare per capita spending growth based on the GDP per capita growth rate would provide a predictable spending path and guarantee savings in years when Medicare per capita spending growth is projected to be higher. Setting a hard cap on per capita spending growth also could create an environment of predictable budgetary discipline that could help payers and providers get health care cost growth under control.

However, there may be acceptable and even desirable reasons to have a relatively higher Medicare per capita spending growth rate, such as to accommodate spending on important but costly advances in medical technology, breakthroughs in treatments, or unanticipated spending to treat pandemic disease outbreaks. In such cases, placing restrictions on the per capita growth rate could force spending reductions in ways that could negatively affect beneficiaries in terms of shifting costs and restricting access, discouraging provider participation in Medicare, and jeopardizing other important safety-net features of the program.

According to the Government Accountability Office (GAO), mandatory spending programs are not amenable to simple budget caps because such caps do not deal with the underlying structure of the program and hence would not address longer-term growth trends that may be a cause for concern (GAO 2011). Congress could, of course, override or revise the caps, but such action would increase spending under current budget rules. And in years when economic growth exceeds Medicare spending growth on a per capita basis, this option would call for no budget restraint, which could lessen the pressure to address flaws in the health care payment and delivery system that recent reforms are designed to address.

The implications of caps as part of a premium support system are unknown. If the bidding systems envisioned by the sponsors succeed in limiting cost growth below the level set by the caps, the caps would have little effect other than as a clear target and backup enforcement mechanism. If the result of bidding under premium support plans is that many plans (or traditional Medicare) are unable to limit their cost growth to the GDP+0.5% (or GDP+1%) cap, the result could be automatic payment reductions and/or premium increases in traditional Medicare and higher beneficiary premiums for private plans, benefit constraints, more limited access to providers through tighter networks, lower provider payments, or some combination of these changes (CBO 2011).

The experience with creating the SGR, a formula-based approach to setting Medicare payment levels for physician reimbursement, provides lessons about adopting a similar approach in order to place limits on overall Medicare spending growth. While the SGR is intended to control the growth in total Medicare spending for physician services, the formula has been widely criticized and never enforced. When spending has exceeded the target, it would trigger deep projected cuts in payment rates which the Congress has typically chosen to override and replace with small fee increases covering brief periods of time. Most times Congress has acted to override the SGR it has had to reduce Medicare spending in other areas. The result has been uncertainty for physicians and their patients, and a weakening of the original cost-containment goals of the SGR. However, while the physician payment updates have not been in line with the steep reductions called for under the SGR formula, the payment updates likely have not been as generous as they might otherwise have been had the formula not been in place.

OPTION 5.3

Introduce a hard cap on the total Federal health care spending per capita growth rate tied to the GDP per capita growth rate

While several recent proposals to impose fiscal discipline on Federal health spending primarily target only Medicare, another option would be to impose a cap on total Federal health care spending, including Medicare, Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program (FEHBP), TRICARE (for members of the military), health insurance exchange subsidies, and the tax subsidy for employer-sponsored health benefits. For instance, the Simpson-Bowles commission proposed that if total Federal health care costs exceeded the target growth rate of GDP+1%, the President and Congress would have to act to lower spending.

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option. As with Option 5.2, a hard cap could be calibrated to achieve whatever Federal savings were desired.

Discussion

According to the GAO, covering the full range of Federal programs and activities under a single budget cap could strengthen the effectiveness of controls and enforcement of budget limits (GAO 2011). Including all Federal health care spending within a budget limit would give the government greater control and certainty regarding a sizeable portion of the Federal budget. Moreover, if health care cost growth is a concern for the U.S. health system overall, then capping Medicare spending growth may raise concerns related to equity, access to care, and quality of care for Medicare beneficiaries. Targeting only Medicare spending could produce a growing disparity between Medicare and other public and private payer reimbursement rates, which could result in access problems among Medicare beneficiaries.

A downside to limiting total Federal health spending with a GDP-based cap is that it would include Medicaid, where program spending operates in a countercyclical manner, rising when the economy is faring poorly. Likewise, TRICARE spending can vary substantially as the nation increases and decreases its defense commitments in response to international events. Also, it is not clear how the limit on the employer tax exclusion would be administered—would it be applied retroactively, across all employers (and employees) equally, and in proportion to the tax subsidy each employer received? Moreover, a budget cap applied to all Federal health care spending could result in spending reductions in all areas even if spending was rising rapidly in only one or a few programs or areas.

References

Click to expand/collapse

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2011. Long-Term Analysis of a Budget Proposal by Chairman Ryan, April 5, 2011.

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2012. The 2012 Long-Term Budget Outlook, June 2012.

Government Accountability Office (GAO). 2011. Budget Process: Enforcing Fiscal Choices, May 4, 2011.

House Budget Committee. 2012. The Path to Prosperity, Fiscal Year 2013 Budget Resolution, March 2012.

Kaiser Family Foundation. 2011. The Independent Payment Advisory Board: A New Approach to Controlling Medicare Spending, April 2011.

Kaiser Family Foundation. 2012a. Comparison of Medicare Premium Support Proposals, March 2012.

Kaiser Family Foundation. 2012b. Medicare Spending and Financing Fact Sheet, October 2012.

Chapin White and Paul Ginsburg. 2012. “Slower Growth in Medicare Spending—Is This the New Normal?” New England Journal of Medicine, March 22, 2012.

Coverage Policy

Options Reviewed

This section discusses several policy options for improving Medicare coverage policy and the often related payment and service use that derives from coverage:

» Increase CMS’ authority to expand evidence-based decision-making

» Mandate coverage with evidence development

» Adopt least costly alternative (LCA) and reference pricing for certain covered services

» Implement prior authorization as a condition of coverage when appropriate

» Allow CMS to use cost considerations in making coverage determinations

While Medicare’s basic benefit package is spelled out in statute, including such broad categories as inpatient care, outpatient care, and physicians’ services, decisions about coverage of a specific treatment or technology are made by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the contractors who review, process, and adjudicate Medicare claims. According to the Medicare statute, Medicare will not pay for items or services that are “not reasonable and necessary for the diagnosis or treatment of illness or injury or to improve the functioning of a malformed body member.”

The process of making Medicare coverage determinations involves examining the available clinical evidence to decide which technologies, services, and treatments demonstrate added-value in medical care and should therefore be covered for payment and under what circumstances. Advances in medicine, whether in the form of new technology or new uses of established technology for diagnosis and treatment, are a leading reason for health care spending growth, both for Medicare and other public and private payers. Furthermore, even widely adopted and used technologies and services may not meet evidence-based tests of effectiveness. Medicare coverage determinations can act as a policy lever to influence both the appropriate use of medical technology and the creation of better evidence to support clinical and health policy decisions. It is a critical element of Medicare’s value-based purchasing philosophy in which the quality of health care services, not quantity, is the driving force (Tunis et al. 2011).

In the view of many, the current process for making Medicare coverage decisions falls short, with some decisions to cover and pay for services made despite a lack of evidence that they actually improve patient outcomes and sometimes resulting from pressure from suppliers and providers of the services (Gillick 2004; Redberg and Walsh 2008). The Medicare process for approving and paying for new services or modified application of existing covered services has been controversial, with some believing that CMS is missing many opportunities for making more accurate judgments about which services actually benefit patients, thereby reducing wasted and sometimes harmful care and spending. Others believe that some decisions of the coverage policy process result in care rationing by interfering with the primacy of patient-physician decision-making on what best serves the patient’s well-being.

Background

Most of the thousands of health care services covered under Medicare have not been subject to a coverage decision. When faced with a coverage decision for a particular service, Medicare has two options: (1) issue a National Coverage Decision (NCD); or (2) issue a Local Coverage Decision (LCD). Medicare now has thousands of LCDs and a growing body of NCDs (Foote and Town 2007); CMS issues about 10-15 NCDs a year. Coverage policies can grant or limit coverage of or exclude items and services from Medicare. Development of LCDs and NCDs requires adherence to structured rules for how they are to be produced, with specified opportunities for affected stakeholder and public input. The resulting coverage policies establish what is supposed to be evidence-based guidance on the appropriate use, if any, for technologies and medical procedures. Medicare Advantage plans are obligated to follow coverage policies that are established as part of traditional Medicare.

When paying for episodes of care, as with diagnosis-related groups for a hospital stay, the attending physicians and hospital generally determine the mix of services offered, including whether particular technologies and procedures will be used. As a result, operationally, coverage determinations generally are reserved for those services which are not part of a bundled payment, unless access to the new technology is a primary reason for the hospital admission, or which are likely to have a major impact on cost and/or quality and safety, whether provided in a bundled payment or not. While LCDs sometimes address requests for new technologies, most policies consider new uses for established technologies and establish utilization guidance for common services. Indeed, most of the coverage activity of Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs) involves establishing utilization guidelines for widely diffused technologies to try to prevent misuse or overuse.

CMS and the MACs often render more nuanced judgments on coverage that place restrictions based on clinical characteristics and setting of care. These so-called “conditions of coverage” have become the norm in NCDs. Yet, studies have suggested that clinicians’ actual practices do not adhere to the evidence-based conditions of coverage in many cases, leading to the likelihood that patients are receiving unapproved interventions that may not benefit them, but which come at a large cost, despite the intent of coverage policy to protect against this outcome (Foote and Town 2007). The MACs lack the resources to assure compliance with coverage conditions; moreover, until recently the Recovery Audit Contractors (RACs), which seek to identify and recover improper Medicare payments, were prohibited from considering coverage adherence in their activities. That prohibition has been lifted, and some expect the RACs to play an increasing role to assess compliance with conditions of coverage given the potentially large savings that could accrue.

While most national coverage decisions result in a positive decision, recent research indicates that many NCDs are based on “fair” or “poor” evidence (Neumann et al. 2008). The lack of high quality evidence for Medicare services means that the vast majority of technologies and services bypass systematic, evidence-based review.

Policy Options

OPTION 5.4

Increase the authority of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to expand evidence-based decision-making

As noted earlier, Medicare coverage policies are often made without strong or relevant evidence, often relying on a small number of studies that lack rigor. Many studies lack head-to-head comparisons with existing diagnosis and treatment options, as comparative effectiveness studies would produce, and many typically do not examine the benefits and harms of technologies for a Medicare-relevant population that includes seniors with multiple comorbidities and younger beneficiaries with disabilities. Moreover, the coverage process has rarely been used proactively to increase the availability and use of high-value services that have been underused, such as smoking cessation programs, or to reduce the use of services that are obsolete or harmful.

One option to address concerns about Medicare coverage policy would be to provide CMS with greater authority (and funding, if necessary) to incorporate high-quality evidence relevant to Medicare services in the coverage determination process. Relying more on the expert advice from the Medicare Evidence Development and Coverage Advisory Committee (MEDCAC), CMS could identify critical research priorities to improve the evidence base and provide these recommendations to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), and Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), as well as private sector research funders for consideration. As an alternative or in addition to this option, CMS could have its own research budget to support relevant research on specific questions related to Medicare coverage. For example, research has shown that some high-growth Medicare services, including sleep studies and spinal injections for back pain, lack a strong evidence base and exemplify substantial practice variation. Clinical experts suggest that these services are being provided inappropriately in many cases (Buntin et al. 2008). This option would transfer more responsibility for coverage decisions to CMS itself to produce evidence-based approaches to making uniform national coverage determinations, rather than relying on the MACs.

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option.

Discussion

An enhanced CMS role on coverage would permit the agency to engage more in establishing a comparative effectiveness agenda relevant to its unique considerations regarding topic selection. The MEDCAC could help CMS craft a more systematic approach to identifying topics for review as NCDs and to develop a research agenda for services for which additional comparative effectiveness research should receive priority. Opponents of expanding CMS’s centralized authority are concerned about the substitution of centralized authority for individual clinicians to determine what interventions best serve patients’ interests. An element of that concern is based on the argument that evidence from clinical studies may be relevant for an average population but perhaps not for an individual patient. Critics also suggest that centralizing CMS’s authority to make coverage policy could lead to varying interpretations of evidence if the agency were under financial pressure to reduce spending. More practically, it is possible that the process of obtaining high-quality evidence could slow down Medicare coverage decisions and, in some cases, could lead to a rejection of new items and services under Medicare, negatively affecting patient care and potentially becoming a disincentive to innovation.

OPTION 5.5

Mandate coverage with evidence development

Often a new technology has important potential for materially improving the health of Medicare beneficiaries although proof of effectiveness has not been produced. The potential health improvement is such that it may not be reasonable to wait until high-quality evidence is developed. In these cases, Medicare has adopted an approach called “coverage with evidence development” (CED), which permits beneficiaries to receive services in the absence of demonstrable evidence of effectiveness, while contributing to developing the needed evidence base. In some cases, the subsequent evidence would provide a basis for removing or limiting the coverage that had been granted. Under the current draft policy for CED, this process links coverage with a requirement that patients receiving the service are enrolled in a clinical trial. This approach permits automatic review of high-quality evidence and a formal determination about coverage in an NCD.

Medicare has applied CED in more than a dozen NCDs in the past 15 years, yet data from the required studies have been used to set coverage policy in only two cases: for lung reduction surgery to treat late-stage emphysema in 2003, with the subsequent NCD based on the results of a randomized clinical trial conducted by NIH, and the use of positron emission tomography (PET) for cancer in 2009 based on oncologists’ reports to the National Oncology PET Registry (the registry approach was previously permitted as part of the CED policy). In both cases, Medicare made positive coverage policies that were likely more permissive than was justified by the available evidence prior to the studies (Buntin et al. 2008). In many other cases that would appear to be candidates for CER, appropriate trials or registries were never designed, funded, or implemented.

Although CMS has issued guidance attempting to clarify current the authority for CED, each application has involved internal legal debate at CMS (Tunis et al. 2011). Without a clear legal mandate to pursue CED, CMS’s efforts have been ad hoc, with no formal process for selecting topics, limited learning from one initiative to the next, and supported by limited resources and staff. To address this issue, one option would be to provide a specific legislative mandate to support the CED process within the Medicare coverage determination process.

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option.

Discussion

Without a clearer legal mandate to pursue CED and additional resources to support data collection, the approach will likely languish. Clinical trials generally are considered the scientifically preferred approach for obtaining the requisite information on which to base a sound coverage determination. Opponents argue that CED inappropriately raises the threshold of evidence needed to obtain a positive coverage decision and slows access to medical advances. Furthermore, requiring entry into a formal clinical trial intentionally limits access for some beneficiaries, either because the trial is limited geographically, because they fail to meet the trial’s patient eligibility criteria, or because they are randomized into the control group.

OPTION 5.6

Adopt least costly alternative (LCA) and reference pricing for certain covered services

CMS generally does not attempt to factor relative effectiveness or cost compared to alternatives in setting payment rates for a covered service. At the same time, MACs have been selectively adjusting prices based on clinical effectiveness evidence for more than 15 years for certain items, including durable medical equipment and a few Part B drugs. Examples include manual wheelchairs, power mobility devices, seat lift mechanisms, supplies for tracheostomy care, and anti-androgen drugs for patients with advanced prostate cancer (MedPAC 2010). Through this approach, known as reference pricing, beneficiaries are allowed to obtain the more costly item if they pay the difference between the approved payment amount for the reference item and the amount for the more costly item.

A recent court decision (Hays v. Sebelius) overturned CMS’s use of the least-costly alternative (LCA), a form of reference pricing, for certain items. The court ruled that because Congress did not specifically authorize LCA approaches when enacting the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003, CMS could not use its broad “reasonable and necessary” authority to do so for pharmaceuticals. In response, Medicare has abandoned the approach in most circumstances.

This option would provide specific statutory authority for adopting LCA for functionally equivalent services in specified circumstances. Under this approach, beneficiaries could still choose the more costly service, but would be liable for the difference between the payment Medicare would make for the least costly alternative and the actual price for the higher-cost alternative.

Some, including MedPAC, have considered an even more robust use of LCA in Medicare, although MedPAC itself has not endorsed the approach (MedPAC 2010). In one version of this option, after a suitable time period needed to generate sufficient evidence, a service judged to be clinically equivalent to another covered alternative would be assigned a payment level equal to that lower-cost alternative (Pearson and Bach 2010). That is, rather than pay based on the actual cost as Medicare does now, services with equivalent clinical effectiveness would be paid the reference (least costly) price. This option goes further by considering a reference price for different interventions that available evidence suggests are clinically equivalent, even though they may be very different on a number of other parameters, such as their mode of administration, their biological mechanisms of action, and patient preferences. In this broader concept, clinical equivalence and LCA pricing then might be applied to interventions that use different treatment modalities, e.g., drugs, surgery, radiation, etc.

Budget effects

MedPAC estimated that the narrow approach to LCA would save $1 billion over 10 years (MedPAC 2011a). No cost estimate is available for the more expansive approach.

Discussion

A rationale for this option is that Medicare beneficiaries and taxpayers should not pay more for a service when a similar service can be used to treat the same condition and produce the same outcome at a lower cost. A more expansive use of LCA than has been applied in the past offers the potential for cost savings because the consideration of clinical equivalence is much broader than LCA’s historically limited use.

Of concern, however, is that this more expansive LCA places a particularly high burden on the strength of the evidence available to determine clinical equivalence, including whether results found in controlled, study environments are replicated when a medication or other intervention is used broadly outside of the research environment. For example, the evidence needed to determine functional equivalence might need to address whether a medication requiring more frequent administration produces the equivalent outcomes as another one with less frequent administration requirements. It often takes many years to produce high-quality evidence to demonstrate comparative effectiveness, yet the proposed approach provides a limited window before a product or service is considered equivalent. Indeed, in some circumstances, paying the lowest price would effectively make the more costly alternative prohibitively expensive, effectively freezing the development of additional evidence and removing the item from the market. The potentially negative impact of LCA on beneficiaries includes facing limited access and/or higher out-of-pocket costs because the item, service, or treatment modality they prefer is not the reference item.

In addition, the more expansive use of LCA might ignore important patient perspectives on equivalence. Although in clinical terms, interventions using different modalities, e.g., surgery vs. drug therapy, might produce comparable outcomes, different patients would likely have different preferences regarding these choices, raising questions about whether these interventions truly are functionally equivalent.

OPTION 5.7

Implement prior authorization as a condition of coverage when appropriate

While commercial health plans and self-funded employer plans have successfully implemented prior authorization for selected services, Medicare has rarely applied this utilization management approach. Recently, MedPAC recommended the use of prior authorization for practitioners who order substantially more advanced imaging services than other physicians treating comparable patients (MedPAC 2011b). According to a recent report by the Government Accountability Office (GAO), doctors who referred patients for tests involving advanced imaging machines that they or a family member owned cost Medicare more than $100 million in 2010 (GAO 2012). It was estimated that providers who self-referred patients for advanced imaging made about 400,000 more referrals than they would have had they not had a financial interest in the imaging equipment.

In addition, the ACA called for a three-year demonstration of prior authorization for motorized wheel chairs prescribed in selected states. The demonstration addresses fraudulent billing as well as inappropriately documented claims paperwork. Since 2009, CMS found it was billed a total of $2.9 billion in fraudulent claims for motorized wheelchairs and that nearly 93% of claims for motorized wheelchairs did not meet paperwork requirements for coverage.

An option could be to require CMS to contract with qualified contractors to perform prior authorization on selected high-cost, high-volume services when there is evidence to suggest that services are used inappropriately. Criteria for conducting prior authorization would be evidence-based and subject to public comment before adoption and would change based on emerging studies. Prior authorization could include exemptions for clinicians and facilities whose profiles demonstrate that their care patterns comply with applicable conditions of coverage and appropriateness criteria.

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option. There is extensive experience with the use of prior authorization by private plans with evidence of cost-effectiveness, suggesting that Medicare could achieve savings under this option.

Discussion

Prior authorization can be effective and reasonably non-intrusive if targeted to services with high unit costs and evidence or high likelihood of substantial inappropriate use; if objective information which may be easily transmitted to reviewers (such as imaging, lab data, and medical reports) are available; if applied in non-urgent or emergency circumstances where there is no patient risk from delays; and for clinical circumstances where there is strong evidence on which to base an objective determination of the appropriateness. Rather than conducting pre- or post-payment review to determine whether conditions of coverage are met, requiring prior authorization would be more effective in ensuring the requested service was in fact reasonable and necessary. Prior authorization would avoid the difficulty of denying payment after resources have already been committed, or trying to collect funds already paid out to providers for services inappropriately delivered.

However, there would be significant increased costs associated with contracting with clinically and organizationally qualified contractors to perform prior authorization. Some providers and patient advocates would likely oppose the introduction of prior authorization rules for Medicare, raising concerns about new administrative burdens and arbitrary denials of needed services. Similar concerns about the use of prior authorization by private health plans in the 1990s led to a significant managed care “backlash” that led many plans to back off such use.

OPTION 5.8

Allow CMS to use cost considerations in making coverage determinations

Accumulated evidence sometimes demonstrates that new, costly technologies offer little or no clinical benefit to patients compared with available alternative and less costly technologies. The Medicare statute does not explicitly address costs, thus leaving ambiguity about whether the “reasonable and necessary” language of the statute can accommodate cost considerations in coverage decisions. In 1989 and again in 2000, CMS sought public comment on proposed rules that would have allowed the agency to consider costs. In both instances, opposition from providers led CMS to withdraw the proposals.

In a recent example, the clinical trial of sipuleucel-T (Provenge) for use in hormone-refractory, metastatic prostate cancer demonstrated an improved survival of 4.1 months compared to a placebo. Priced at about $30,000 per treatment, with a usual course of three treatments, Medicare coverage came at a cost of nearly $100,000 per patient for this short-term average extension of life (Kantoff et al. 2010).

Yet, current interpretation of law would preclude CMS in any way from considering whether this cost represents a prudent use of funds. Both CBO and MedPAC have recently expressed the opinion that regardless of the legal interpretation of the current statute, CMS would require clear statutory authority to formally consider costs in determining whether to cover and pay for services (CBO 2007; MedPAC 2008). In the ACA, Congress expressly prohibited Medicare from considering costs in making coverage decisions. This option would give CMS legislative authority to use cost considerations in making coverage determinations.

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option.

Discussion

The basic reason to consider costs is to achieve higher value for Medicare spending. A concern is that in some cases, services provided at high cost do not improve patient well-being and sometimes even subject patients to potential harm. The aim of an option to establish a more disciplined process for considering costs, but falling short of basing coverage on the results of cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA), would be to achieve higher value. A number of methodological issues make reliance solely on CEA, and the common output of CEA, the calculation of cost per quality-adjusted life year, problematic (Gold et al. 2007). Many other countries do not use CEA formally to determine whether a new service should be covered and paid for, but they do use CEA results as information to be considered in coming to a decision on coverage (Neuman and Greenberg 2009; Garber and Sox 2010).

Opponents argue that any consideration of costs in making coverage determinations raises the specter of care rationing. As with the Least Costly Alternative option, actively considering costs, with the possibility of denying coverage for services that do not have a sufficiently high pay-off in terms of improved health outcomes, places a high burden on the strength of the evidence available to make such judgments. This concern could be ameliorated somewhat if CMS had access to more comparative effectiveness studies, particularly controlled clinical trials, on which to base judgments that include cost and quality trade-offs.

References

Click to expand/collapse

Melinda Buntin, Steve Zuckerman, Robert Berenson, et al. 2008. “Volume Growth in Medicare: An Investigation of Ten Physician Services,” RAND Health and The Urban Institute, Working Paper Prepared for the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2008.

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2007. Research on the Comparative Effectiveness of Medical Treatments, December 2007.

Susan Bartlett Foote and Robert J. Town. 2007. “Implementing Evidence-Based Medicine Through Medicare Coverage Decisions,” Health Affairs, November 2007.

Alan Garber and Harold Sox. 2010. “The Role of Costs in Comparative Effectiveness Research,” Health Affairs, October 2010.

Muriel Gillick. 2004. “Medicare Coverage for Technological Innovations: Time for New Criteria?” New England Journal of Medicine, May 20, 2004.

Marthe Gold, Shoshanna Sofaer, and Taryn Siegelberg. 2007. “Medicare and Cost-Effectiveness Analysis: Time to Ask the Taxpayers,” Health Affairs, September/October 2007.

Government Accountability Office (GAO). 2003. Medicare: Divided Authority for Policies on Coverage of Procedures and Devices Results in Inequities, 2003.

Government Accountability Office (GAO). 2012. Higher Use of Advanced Imaging Services by Providers Who Self-Refer Costing Medicare Millions, 2012.

Philip Kantoff, Celestia Higano, Neal Shore, et al. 2010. “Sipuleucel-T Immunotherapy for Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer,” New England Journal of Medicine, July 29, 2010.

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). 2003. Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy, March 2003.

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). 2008. Report to the Congress: Reforming the Delivery System, June 2008.

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). 2010. Report to the Congress: Enhancing Medicare’s Ability to Innovate, June 2010.

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). 2011a. “Moving Forward from the Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) System,” Letter to Chairmen and Ranking Members of Congressional Committees of Jurisdiction, October 14, 2011.

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). 2011b. Report to the Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System, June 2011.

Peter J. Neumann, Maki S. Kamae, and Jennifer A. Palmer. 2008. “Medicare’s National Coverage Decisions for Technology,” Health Affairs, November 2008.

Peter J. Neumann and Dan Greenberg. 2009. “Is the United States Ready for QALYs?” Health Affairs, September/October 2009.

Steven D. Pearson and Peter B. Bach. 2010. “How Medicare Could Use Comparative Effectiveness Research In Deciding On New Coverage And Reimbursement,” Health Affairs, October 2010.

Rita Redberg and Judith Walsh. 2008. “Pay Now, Benefits May Follow: The Case of Cardiac Computed Tomographic Angiography,” New England Journal of Medicine, November 27, 2008.

Sean R. Tunis, Robert A. Berenson, Steve E. Phurrough, and Penny E. Mohr. 2011. Improving the Quality and Efficiency of the Medicare Program Through Coverage Policy, The Urban Institute, August 2011.

Governance and Management

Options Reviewed

This section reviews options for changes to Medicare governance and management in three areas:

» Changes to IPAB and CMMI

» Revise CMS governance and oversight authority

» Enhance the administrative capacity of CMS

Medicare governance and management issues have been an element of reform discussions for many years. At issue is the degree of authority and autonomy the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), or others in the Executive Branch, should have in administering the Medicare program within statutory parameters. Congress ultimately is responsible for setting policy and funding levels for the Federal government, and the Executive Branch is responsible for implementing those laws within the funding constraints that are established. Concerns have arisen about the ability of Congress to deal with the often exceptionally detailed technical Medicare policy issues in a timely manner in what is often an intensely political environment. Some have expressed concern with Congress’ tendency to intervene when the agency makes a decision that key stakeholders find troublesome. There also are concerns about the ability of CMS to manage the current program while pursuing innovations needed in a changing marketplace. Finally, CMS has tight resource constraints.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) included two policies designed, in part, to address concerns about Medicare governance and management. It creates an Independent Payment Advisory Board (IPAB), and sets annual targets for the growth rate in total Medicare spending. If spending is not within those targets, the law requires IPAB to issue recommendations to bring spending in line with those targets. Those recommendations must be considered by Congress on a fast-track basis and, if the Congress fails to act, the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) must implement the recommendations, also on a fast-track basis.

The ACA also established a new Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) with $10 billion in funding over 10 years and a mandate to test a variety of models for payment and delivery system reform for Medicare and Medicaid. The law authorizes CMS to broadly disseminate those changes if certain cost and quality criteria are met.

Policy Options

Changes to IPAB and CMMI

Creation of IPAB, in particular, has generated concerns and led to conflicting proposals, ranging from efforts to repeal or strengthen it. Concerns about CMMI have also been a topic of debate.

OPTION 5.9

Revise authority of or eliminate the Independent Payment Advisory Board (IPAB)

IPAB is a 15-member board tasked with recommending Medicare spending reductions to Congress if projected spending growth exceeds target levels. Members are to be nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate. The law sets a target for the growth rate in Medicare spending per capita. For 2015 to 2019, the target is the average of general and medical inflation. For 2020 and beyond, the target is the increase in the gross domestic product (GDP) plus one percentage point. If Medicare spending exceeds the target, the law requires IPAB to make specific recommendations to bring spending in line with those targets in that year. IPAB cannot recommend reductions of more than 0.5 percent of Medicare spending in 2015, 1.0 percent in 2016, 1.25 percent in 2017, and 1.5 percent in 2018 and subsequent years. The board is prohibited from recommending changes in premiums, benefits, eligibility, taxes, or other changes that would result in rationing. If IPAB cannot agree on recommendations, the HHS Secretary is responsible for making recommendations to reach the statutory spending target. Recommendations by IPAB or the Secretary must be considered by Congress on a fast-track basis, and if the Congress fails to reject them or to come up with alternatives that reach the same level of savings, HHS must implement the recommendations, also on a fast-track basis.

There is no statutory timetable for the President to submit nominations to the board, and the concerns about IPAB raise a strong possibility of resistance to confirmation of nominees. The first year of potential activity by IPAB is 2013. In April of 2013, the CMS Actuary will make the first determination of whether spending is within the target for the initial effective year, 2015. If spending exceeds the target, IPAB would develop its recommendations during the remainder of 2013 and transmit them to Congress in January 2014. The Secretary would begin to implement the recommendations, in the absence of Congressional action, in August 2014, effective for 2015.

OPTION 5.9A

Broaden IPAB’s authority

Some have proposed giving IPAB more authority by allowing it to weigh in on a broader array of issues including those affecting different provider groups. For example, the Simpson-Bowles commission recommended broadening IPAB’s authority to include payment rates for all providers since some provider types are exempted from IPAB recommendations before 2020 under current law. The Obama Administration proposed extending its authority to include recommendations on value-based benefit design, as did the Domenici-Rivlin Debt Reduction Task Force.1 Others have suggested expanding IPAB’s authority to include private sector health payments.

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option.

Discussion

Advocates for broadening IPAB’s authority suggest that if an independent board is to be in place, its authority should not be limited to just some providers or to managing payment rates and ignoring new or innovative ways to address broader concerns over health care cost growth system-wide. Instead, such a board could advance more substantial reforms affecting other aspects of Medicare that may be difficult to consider in a political environment. Some also would extend its authority to include private sector changes as well so as to address total costs and ensure that Medicare payments do not fall too much out of line with private payment rates. Concern about extending IPAB’s authority reflects the general concerns about IPAB: in particular, that this entity should not be empowered to make changes beyond Medicare payment rates in order to advance structural or benefit changes, with fast-track consideration, because such major policy decisions should rest with the Congress, not an appointed body.

OPTION 5.9B

Change to multi-year targets and savings

The spending targets and scoring of IPAB recommendations could be set over a multi-year period rather than for a single year as under current law. For example, rather than look just to the single “implementation year,” the test of projected Medicare spending, and IPAB’s required savings recommendations, could be on a multi-year basis.

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option.

Discussion

Under current law, IPAB recommendations are required to achieve savings in a single year (the “implementation year”). For example, in 2013, the CMS actuary is required to determine if projected spending in 2015 will exceed the target, and if so, IPAB would be required to develop recommendations to reduce spending by a certain amount in 2015. (The only longer-term requirement is that the recommendations cannot increase total Medicare spending over the baseline over a 10-year period.)

However, focusing on savings in only one year may lead to standard and easily scoreable short-term recommendations, such as payment update reductions, rather than long-term delivery system reforms and other approaches that could achieve savings over a multiple-year period but might not produce the requisite savings in any single year. Long-term reforms may require several years to implement before scoreable savings accrue, so could not be used by IPAB or by Congress to reach the one-year target for spending reductions. Yet these approaches may be the type of reforms that are more likely to put Medicare on a sustainable long-term path than provider payment cuts alone. A concern with this option is that it is harder to score some of these long-term reforms, and savings are less certain to be achieved. It would be important to ensure that moving to a longer timeframe for achieving savings would not mean that the required level of savings was less likely to be achieved.

OPTION 5.9C

Repeal or revise the authority of IPAB

Proposals have been made to repeal IPAB (its targets and its enforcement). During the 112th Congress, the House of Representatives voted for such a repeal but the Senate did not act on the legislation. Congress did, however, reduce IPAB’s mandatory appropriation for Fiscal Year 2012 funded through the ACA from $15 million to $5 million.

Budget effects

When the ACA was enacted in 2010, CBO estimated that IPAB would save $15.5 billion between 2015 and 2018. Based on the current projections, CBO indicates that Medicare spending will be below the targets and therefore the IPAB process will not be triggered. However, CBO estimates that repeal of IPAB would cost about $3.1 billion over 10 years (2013–2022), based on the assumption that there is a probability that its Medicare spending projections may be wrong (CBO 2012b).

Discussion

Those who propose repealing IPAB say it is unwise to empower a group of unelected officials to make decisions about Medicare policy and that those decisions should be made by Congress through the traditional legislative process. Those favoring retaining IPAB argue that a “back-up” mechanism is needed in the event per-capita Medicare spending accelerates. They also believe independent experts would be more immune to political pressures and lobbying than either the Congress or the Administration.

OPTION 5.10

Revise or eliminate the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI)

CMMI has authority to test a wide range of innovations and broadly disseminate those that CMS determines meet tests of costs and quality. CMMI has in its first two years implemented a wide range of programs, such as tests of Pioneer Accountable Care Organizations, a multi-payer Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative, and State Innovation models. The ACA also provides CMMI with mandatory appropriations totaling $10 billion over 10 years. CBO estimated that the savings generated by innovations would offset the spending, with a net savings estimate of $1.3 billion over 10 years. While the debate over CMMI is not as heated as the debate over IPAB, similar options could be considered—either repeal or restrain CMMI’s authority, or enhance CMMI’s authority.

Budget effects

No cost estimates are available for these options.

Discussion

Arguments to repeal CMMI or constrain its authority focus on several issues. There are concerns about the initial mandatory 10-year funding rather than subjecting CMMI activities to the year-by-year appropriations process that most Federal programs are subject to. There are questions about how CMMI uses the breadth of its demonstration authority in both Medicare and Medicaid without Congressional review, and concerns about particular demonstration programs. Finally, the ability of CMS to broadly disseminate models that it tests raises questions about the balance between Executive branch and Congressional responsibilities for deciding about nationwide programmatic changes.

Advocates for more rapid innovation in Medicare see CMMI as a needed accelerator of that agenda, which has been constrained for years by a lack of funding for innovation and constraints on the authority of CMS both to test models and to more broadly disseminate models that appear to be successful. At a minimum, advocates of CMMI suggest that the center be given an opportunity to test its value in pursuing innovations that achieve its mission of lowering spending while increasing, or at least not reducing, the quality of care.

OPTION 5.11

Provide more independent administration of CMS

Organizations including the National Academy of Social Insurance (NASI), the National Academy of Public Administration, and the Bipartisan Commission on the Future of Medicare, and other independent policy experts have examined Medicare’s governance and administration and offered an array of alternative administrative models. These include making CMS an independent agency or creating an independent board to oversee Medicare and perhaps health care more broadly, based on models such as the Securities and Exchange Commission or the Federal Reserve Board.

Under the independent agency approach, CMS would be removed from the Department of Health and Human Services and made an independent agency, bringing its current funding and staff as well as appropriate allocations of funding and staff from other HHS offices that focus in part on CMS issues. The CMS Administrator would continue to be appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate, but would have a fixed-term appointment spanning two presidential terms, and there would be an independent board providing him or her advice and oversight (NASI 2002).2

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option.

Discussion

There are tradeoffs involved in such a shift. The CMS administrator would be accountable to the President, with the standing that accompanies that position, and would no longer be subject to HHS oversight, direction, or interference. But the agency would lose the substantive input and political buffer of a Cabinet Secretary overseeing and protecting the agency. It is unclear whether Congress would be more or less likely to intervene in agency decisions, and whether having a separate independent advisory board would provide a balanced combination of substantive advice and protection from political interference. The fixed term for the administrator would be designed to span presidential terms, providing leadership continuity. However, that would result in a key agency with substantial impact on the Federal budget being led in some years by someone who may or may not be in agreement with the priorities of the incumbent President.

A key question in such a design would be whether the CMS Administrator and the agency would have powers in administering payment policy, such as authority to test and implement payment reform models of the type under consideration at CMMI. Becoming an independent agency would not lessen the difficulties inherent in defining and separating out those policy decisions that appropriately belong in the political arena, due to the magnitude of Medicare’s programmatic and economic impact on health care and the economy, from those that may best be left to administrative discretion.

OPTION 5.12

Establish oversight structure for premium support model

The premium support model (see Section Four, Premium Support) typically is accompanied with new mechanisms for oversight of the program, including:

» a new structure to oversee competition among health plans, and

» a new approach for administering Medicare on a regional basis as one of the competing plans.

One approach would have a board or other mechanism oversee and manage competition among private health insurers and traditional Medicare (Butler and Moffit 1995; National Bipartisan Commission on the Future of Medicare 1999; Antos et al. 2012). Advocates compare this model to the current oversight by the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) of the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program (FEHBP), as well as to the new Health Insurance Exchanges established under the Affordable Care Act. Depending on the premium support design, this entity could have responsibilities ranging from approval of benefit plans to setting and managing the annual and periodic open enrollment periods, as well as overseeing the plans that are serving the program.

The premium support model also requires attention to how to administer traditional Medicare as a competing plan. Under one scenario, traditional Medicare would be run nationally and bid locally. An alternative approach that has been advanced would have traditional Medicare run by regional administrators with a degree of autonomy over payment and possibly even elements of benefit design.

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option.

Discussion

Proponents cite the experience of OPM in overseeing FEHBP as a model. Premium support advocates believe that CMS should not be in a position to manage one competitor (traditional Medicare) and at the same time fairly oversee a competitive market that includes private plans competing with that traditional program.

Critics worry that Medicare, with its vulnerable beneficiaries, is more complex than FEHBP. The combination of an OPM-like oversight structure with CMS administering the traditional program could present a problem of dual accountability for Medicare and could leave skeptics asking: Who ultimately is responsible for Medicare?

Administering Medicare on a regional basis would allow traditional Medicare to compete against private insurers in regional markets in a premium support model, thereby remaining a viable option for beneficiaries. This could, however, lead to a greater degree of variability in Medicare around the nation. There are questions about oversight and the capacity of regional officials to make these decisions and still achieve a degree of national autonomy for the program.

Enhance CMS Administrative Capacity

OPTION 5.13

Enhance CMS administrative capacities through contractors

Medicare operates largely through Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs), private sector entities (typically related to or affiliated with insurers) that contract with CMS to administer the program and pay claims. CMS could turn to such entities, or other contractors, to more actively manage the program in a manner analogous to the way that large employers use third-party administrators to manage employer-sponsored health benefits.

The options can range along a spectrum from management of a particular service to a broader model that provides a range of care management functions. One option for a particular service is to contract with radiology benefit managers to administer prior authorization for advanced imaging services. Such administrators already have experience with this function in the private sector, approving payments for specific advanced imaging services ordered by physicians based on recommended guidelines for clinical practice. (For a discussion of the more general use of prior authorization, see Section Five, Coverage Policy.)

Medicare could contract for a more aggressive set of care management tools. These could range from high-cost case management and chronic care management approaches to network management and consumer engagement (UnitedHealth Center for Health Reform & Modernization 2013).

Budget effects

CBO has estimated that prior authorization for advanced imaging services under Medicare would produce net savings of $1 billion over 10 years (2010–2019) (CBO 2008). However, in 2012, CBO estimated that a proposal in President Obama’s Fiscal Year (FY) 2013 Budget to require prior authorization for advanced imaging would not produce budget savings over the 10-year budget window (2013–2022) (CBO 2012a). No cost estimate is available for the broader approach to contracting for care management.

Discussion

These approaches seek to make management of Medicare more analogous to the care management approaches used in private sector health plans. In particular, they attempt to focus on more appropriate utilization, which entails more attention to preventive measures and adherence to prescription medicine and other care recommendations, as well as attention to high-cost case management and clinical guidelines for interventions whose benefit may be less clear.

At the same time, there is a need for clear evidence of both clinical relevance and sustained cost containment. Introducing such approaches into traditional Medicare would be a major change for providers and patients, and would require a degree of acceptance in order to be sustainable. Some have suggested providing such approaches as an option for beneficiaries, who could choose between such a more managed Medicare program or the more traditional approach, presumably with some shared savings if the managed approach lowers spending. Finally, any such approach would require processes for appropriate adjudication of appeals.

OPTION 5.14

Increase CMS resources

CMS’s operating capacity has been constrained as its responsibilities have increased but its staffing and administrative funding have not. While Medicare’s programmatic dollars are funded as entitlements, the administrative budget must compete for annual appropriations. Today, CMS operates with about 4,500 full-time employees while overseeing more than $835 billion in annual spending, including $550 billion in Medicare spending. In 1977, CMS had a staff of 4,000 and annual spending of about $30 billion. Concerns about CMS resources are long-standing. In 1999, 14 national health care leaders (including former CMS Administrators from both parties) published an open letter attributing the agency’s management difficulties to an unwillingness to “provide the resources and flexibility necessary to carry out its mammoth assignment” (Open Letter to Congress and Executive 1999). One option would be to fund the CMS administrative budget fully out of the Medicare Part A trust fund so that the funding is not competing for annual appropriations.

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option. The budget effects can be calibrated to specific levels of increased spending. For example, if Medicare’s spending for administration was 2 percent of program spending instead of the current 1.5 percent, administrative spending would increase by about $2.6 billion.

Discussion

The argument for an increase in funding is the need to not only administer the current program effectively for beneficiaries and taxpayers, but also to implement the types of changes identified in this report. However, given Federal budget constraints, action to increase spending would compete with other policy needs and funding priorities.

References

Click to expand/collapse

Joseph R. Antos, Mark V. Pauly and Gail Wilensky. 2012. “Bending the Cost Curve through Market-Based Incentives,” New England Journal of Medicine, August 1, 2012.

Stuart M. Butler and Robert E. Moffit. 1995. “The FEHBP as a Model for a New Medicare Program,” Health Affairs, Winter 1995.

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2008. Budget Options, Volume 1: Health Care, December 2008.

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2012a. Analysis of the President’s FY 2013 Budget, March 2012.

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2012b. Cost Estimate, H.R. 452: Medicare Decisions Accountability Act of 2011, March 2012.

Lynn Etheredge. 1997. “Promarket Regulation: An SEC-FASB Model,” Health Affairs, November/December 1997.

National Academy of Social Insurance (NASI). 2002. Improving Medicare’s Governance and Management, July 2002.

National Academy of Social Insurance and National Academy of Public Administration. 2009. Designing Administrative Organizations for Health Reform, 2009.

National Bipartisan Commission on the Future of Medicare. 1999. Building a Better Medicare for Today and Tomorrow, March 1999.

Open Letter to Congress and the Executive. 1999. “Crisis Facing HCFA & Millions of Americans,” Health Affairs, January/February 1999.

Hoangmai H. Pham, Paul B. Ginsburg, and James M. Verdier. 2009. “Medicare Governance and Payment Policy,” Health Affairs, September/October, 2009.

UnitedHealth Center for Health Reform & Modernization. 2013. Medicare and Medicaid: Savings Opportunities from Health Care Modernization, Working Paper 9, January 2013.

Program Integrity

Options Reviewed

This section discusses options to reduce fraud and abuse in Medicare, organized in the following categories:

» Raise the requirements that certain high-risk provider groups must meet in order to enroll and stay enrolled in Medicare

» Institute new pre-payment screens for high-risk providers

» Increase post-payment review of suspicious claims

» Expand enforcement sanctions and penalties

» Improve Medicare administration through better contractor oversight, data sharing, and funding levels that maximize return on investment

» Increase efforts to identify fraud and abuse in Medicare Part C (Medicare Advantage) and Part D (the prescription drug program)

» Revisit physician ownership rules to mitigate over-utilization

Finding ways to reduce fraud and abuse is essential for reducing health care costs and protecting Medicare beneficiaries. The sheer size of the Medicare program is, perhaps, one of the biggest challenges in fighting Medicare fraud and abuse. On each business day, Medicare’s contractors process about 4.5 million claims from 1.5 million providers. Each month, Medicare contractors review 30,000 enrollment applications from health care providers and medical equipment suppliers. Adding to this complexity, Medicare is designed to enroll “any willing provider,” and must pay most claims within 30 days. This leaves relatively few resources to review claims to ensure that they are accurate and complete and submitted by legitimate providers.

The scope of fraud and abuse in Medicare, while substantial, has not been fully documented. By its very nature, fraud is difficult to detect, as those involved are engaged in intentional deception. For example, fraud may involve providers submitting a claim with false documentation for services not provided, while the claim on its face may appear valid. Fraud also can involve efforts to hide ownership of companies or kickbacks to obtain beneficiary information or provide services to beneficiaries. In 2011, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) estimated that improper payments in Medicare—which include fraud, abuse, and erroneous payments—accounted for almost $48 billion in Fiscal Year 2010 (GAO 2011b). Efforts to find and fight fraud and abuse in Medicare have made considerable progress in recent years.

Background