2016 Survey of Americans on the U.S. Role in Global Health

Section 1: Views of U.S. Role in World Affairs and in Global Health Efforts

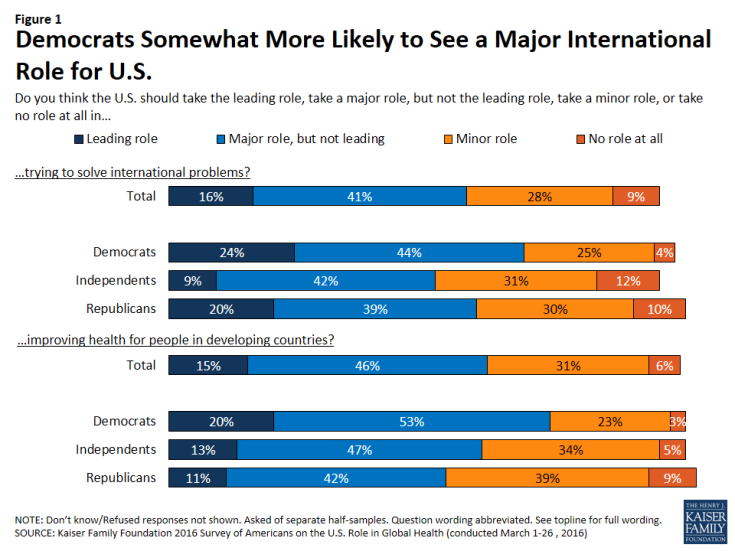

Most See a Major Role for U.S. in World Affairs Generally and in Global Health Specifically

Broadly, the public is largely supportive of the U.S. playing a significant role in trying to solve international problems. About six in ten Americans (57 percent) say the U.S. should play at least a major role in world affairs, including 16 percent who say the U.S. should take the leading role and 41 percent who say the U.S. should play a major role but not the leading one. This is a decline from December 2015, when 65 percent said the U.S. should play at least a major role in world affairs, but similar to results from 2012.

| Table 1: Majority Say U.S. Should Take Major or Leading Role in World Affairs | |||

| I would like you think about the role the U.S. should play in trying to solve international problems. Do you think the U.S. should take… |

2012 | 2015 | 2016 |

| …a leading role in world affairs | 17% | 18% | 16% |

| …a major role, but not the leading role | 43 | 47 | 41 |

| …a minor role | 26 | 24 | 28 |

| …no role at all in world affairs | 11 | 9 | 9 |

| Don’t know/Refused | 3 | 2 | 5 |

Similarly, six in ten Americans (61 percent) say the U.S. should play at least a major role in improving health for people in developing countries, including 15 percent who say we should take the “leading role” and 46 percent who say a “major role.” While majorities of Democrats, Republicans, and independents say the U.S. should take at least a major role in trying to solve international problems and improving health for people in developing countries, Democrats are somewhat more likely to support such a role.

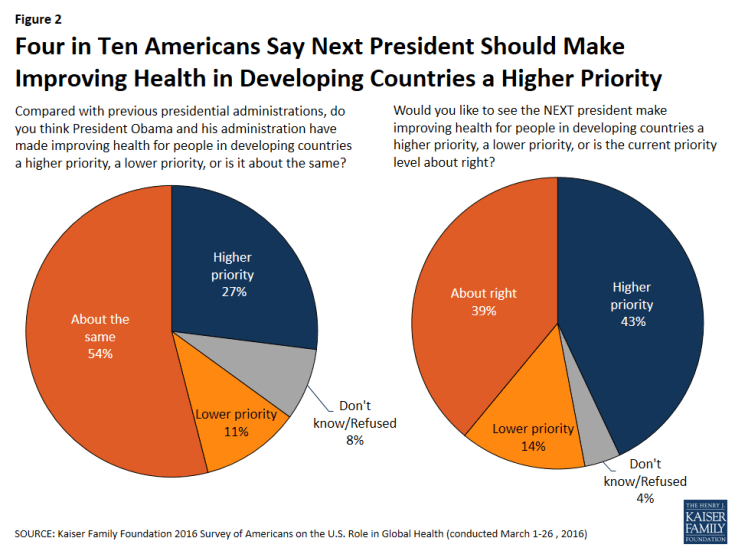

The majority of Americans think President Obama and his administration have made improving health for people in developing countries about the same level of a priority (54 percent) or a higher priority (27), compared to previous presidential administrations, with only about one in ten (11 percent) saying President Obama has made it a lower priority. Consistent with the overall sense that the U.S. should take a major role in this area, over four in ten (43 percent) say they would like the next president to make improving health for people in developing countries an even higher priority, while a similar share (39 percent) say the current priority level is about right and just 14 percent would like it to be a lower priority. Democrats are more likely to say that President Obama has made improving health a higher priority (38 percent) and are more likely to say they would like to see the next president make it a higher priority (53 percent) compared with independents (23 percent and 42 percent) or Republicans (21 percent and 31 percent).

Figure 2: Four in Ten Americans Say Next President Should Make Improving Health in Developing Countries a Higher Priority

Improving Health in Developing Countries Viewed as One of Many Important Priorities

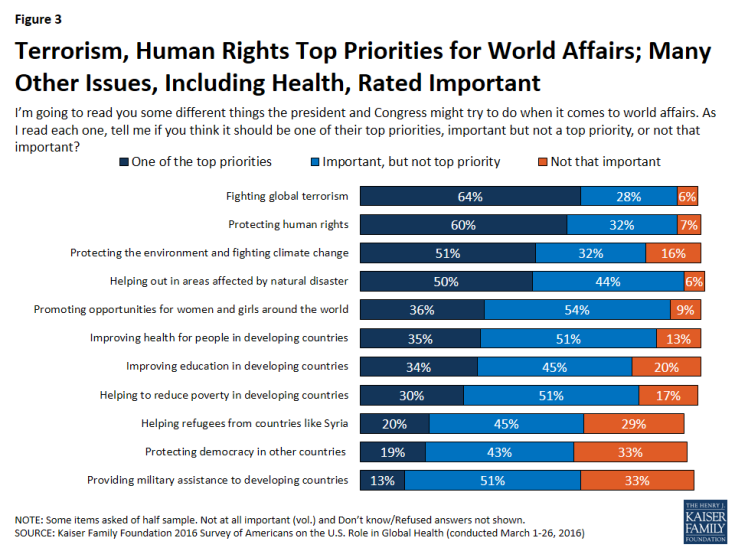

When it comes to different ways in which the U.S. might engage in world affairs, fighting global terrorism (64 percent) and protecting human rights (60 percent) top the public’s priority list. These are closely followed by protecting the environment and fighting climate change (51 percent) and helping out in areas affected by natural disaster (50 percent).

While improving health for people in developing countries does not top the list of priorities, more than one-third (35 percent) of Americans say it is one of the top priorities, and another 51 percent deem it an important priority. This is similar to the share that say promoting opportunities for women and girls around the world (36 percent) and improving education in developing countries (34 percent) are a top priority, and slightly more than the share who say helping to reduce poverty in developing countries (30 percent) is a top priority. Fewer prioritize helping refugees from countries like Syria (20 percent), promoting democracy in other countries (19 percent), and providing military assistance to developing countries (13 percent).

Figure 3: Terrorism, Human Rights Top Priorities for World Affairs; Many Other Issues, Including Health, Rated Important

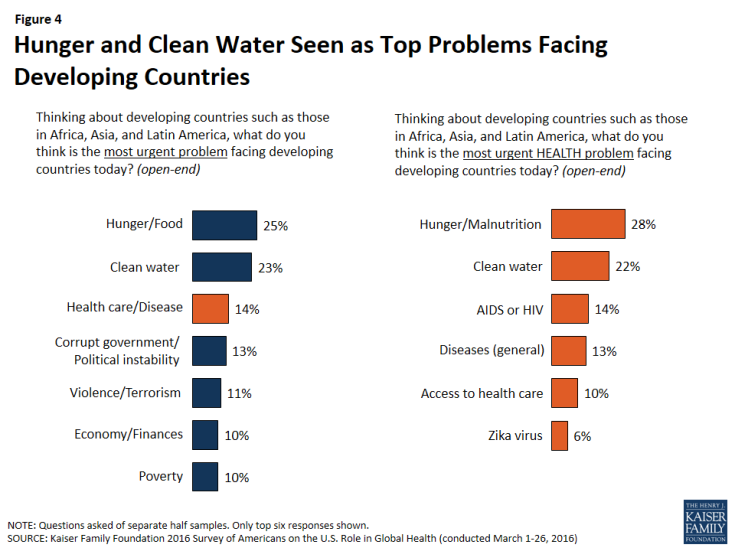

Despite the fact that improving health for people in developing countries does not top the public’s list of priorities for world affairs, two issues related to health – hunger and clean water – are named by the largest shares of Americans as the most urgent problems facing developing countries. In an open-ended question, one in four Americans name hunger or lack of food as the most urgent problem facing developing countries, followed closely by 23 percent who mention clean water. When the question is framed in terms of the most urgent health problem facing developing countries, the top two responses are similar: 28 percent name hunger or malnutrition and 22 percent say clean water.

The share of Americans who name clean water as an urgent problem in both these questions has increased significantly in the past four years. In 2012, only 7 percent of Americans said that clean water was one of the most urgent problems facing developing countries, and just 12 percent named it as the one of the most urgent health problems. The increased concern regarding access to clean water in developing countries may be due to recent media attention about water quality issues in the U.S., particularly surrounding the water crisis in Flint, Michigan.

| Table 2: Percent of Americans Who Say Clean Water is an Urgent Problem | |||

| 2012 | 2016 | Percent Change from 2012 to 2016 | |

| Clean water is an urgent problem | 7% | 23% | +16 percentage points |

| Clean water is an urgent HEALTH problem | 12 | 22 | +10 percentage points |

The focus on clean water and reducing hunger is also evident in opinions about priorities for U.S. efforts to improve health in developing countries. Topping the list, 69 percent of Americans say that improving access to clean water should be one of the top priorities. This is slightly more than the percent who say by combating global outbreaks of diseases like Ebola and Zika (62 percent), improving children’s health (61 percent), and reducing hunger and malnutrition (61 percent) are top health priorities. While others – including combatting specific diseases like HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, and polio as well as improving access to family planning – fall farther down the list, majorities of the public view each one of these areas as important, with fewer than a quarter saying each is “not that important.”

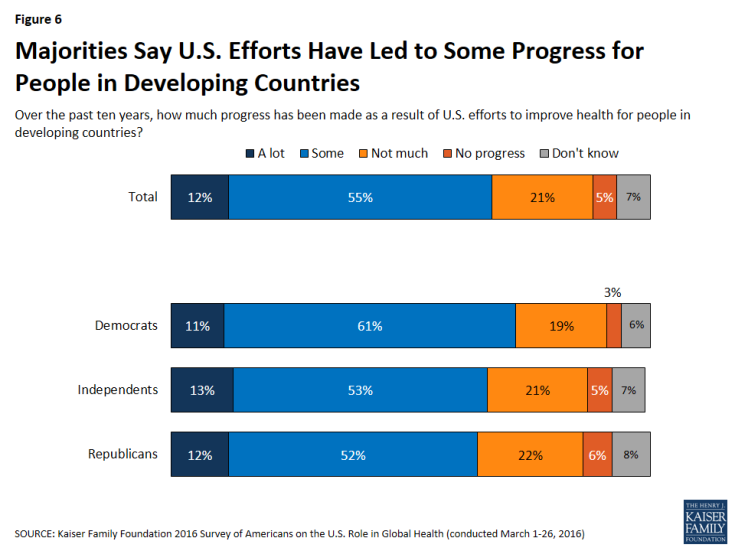

Mixed Attitudes on Whether U.S. Efforts Have Led To Progress

When asked about the success of U.S. global health efforts to date, the majority of the public, 67 percent, believes that over the past ten years, at least some progress has been made as a result of U.S. efforts to improve the health for people in developing countries, though relatively few (12 percent) feel that “a lot” of progress has been made. These views are shared across the political spectrum, with large shares of Democrats, independents, and Republicans all saying that at least some progress has been made.

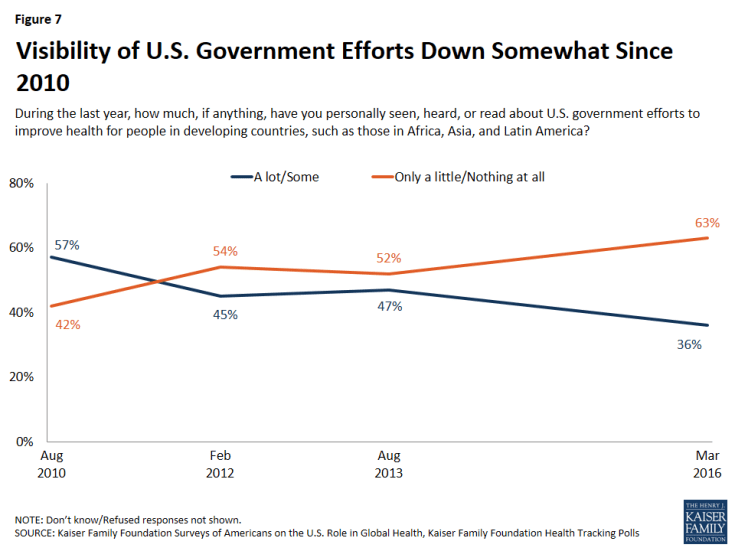

At the same time that most Americans believe progress has been made as a result of U.S. global health efforts, overall visibility of these efforts appears to have decreased. Just over a third (36 percent) of the public in the most recent survey say that in the past year they have heard “a lot” or “some” about U.S. government efforts to improve health for people in developing countries, down from nearly half in 2013 and 2012, and 57 percent in 2010.

More Support For Global Health Spending Than For Foreign Aid

Previous Kaiser surveys have found that the public vastly overestimates the amount of the federal budget that is actually spent on foreign aid. In December 2015, just 3 percent of Americans correctly stated that 1 percent or less of the federal budget is spent on foreign aid, and on average, Americans say spending on foreign aid makes up 31 percent of the federal budget.1 The 2016 survey finds that half of Americans say the U.S. is spending “too much” on foreign aid while only one in five say the U.S. is spending “too little” (19 percent) or the right amount (21 percent). Yet, after hearing the fact that foreign aid spending is about one percent of the federal budget, the percent of individuals who say spending is “too much” drops from 49 percent to 30 percent.

Figure 8: Half of Americans Say U.S. is Spending Too Much on Foreign Aid Until They Know Actual Spending Amount

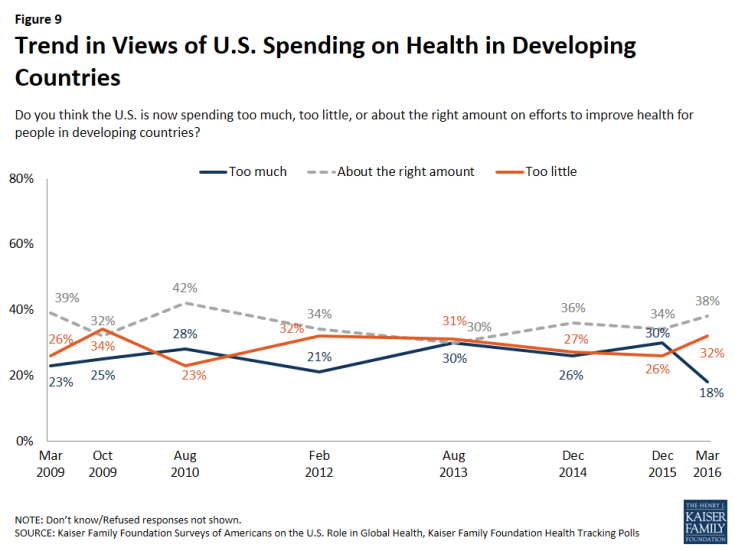

The public is more supportive of U.S. spending on global health than foreign aid more generally. When asked specifically about global health spending, seven in ten say the U.S. is now spending too little (32 percent) or about the right amount (38 percent) on efforts to improve health for people in developing countries, and fewer than one-fifth say the U.S. is spending too much (18 percent). Over time, opinions on U.S. spending on improving health in developing countries have remained fairly stable, but the most recent survey does record the lowest share (18 percent) of Americans saying that the U.S. is spending too much on health in developing countries. This share is down from 30 percent in December 2015, a decrease that was seen across partisan subgroups.

Partisan Differences In Views On U.S. Global Health Spending

Similar to partisan differences on the role of government and federal spending on domestic priorities found in other surveys, there are differences in views of U. S. spending on global health by political party identification. Democrats are more likely to say the country is spending “too little” than “too much” (49 percent vs. 9 percent), whereas Republicans are more likely to say the opposite, that the country is spending “too much” rather than “too little” (31 percent vs. 14 percent). Independents fall in the middle, with 32 percent saying the U.S. spends “too little” and 18 percent saying the U.S. spends “too much” on health in developing countries.

At the same time that the public generally supports maintaining or increasing government spending on health in developing countries, there is also doubt about the potential effectiveness of increased spending from the U.S. and other developed nations. More than half of Americans (57 percent) believe that spending more money will not make much of a difference in improving health for people in developing countries, while about four in ten (39 percent) say that more spending will lead to meaningful progress.

Republicans and independents are particularly skeptical, with majorities saying increased spending will not make much of a difference, 71 percent and 60 percent, respectively. This is compared to nearly six in ten Democrats (56 percent) who say increased spending will lead to meaningful progress and 42 percent who say increased spending will not make much of a difference.

These partisan differences have increased over time, from a margin of 13 percentage points separating the shares of Republicans and Democrats who believed spending more would lead to progress in 2009, compared to a difference of 32 percentage points today.

Americans see a variety of benefits, both at home and abroad, to U.S. spending to improve health in developing countries. About three-fourths (74 percent) say such spending helps protect the health of Americans by preventing the spread of diseases like Ebola and Zika, and nearly six in ten (59 percent) say it helps to improve the image of the U.S. throughout the world. Two-thirds (68 percent) also believe such spending helps make people and communities in developing countries more self-sufficient. Americans are more skeptical about the impact of such spending on U.S. national security and the U.S. economy, with about four in ten saying spending helps in these areas (41 percent each) and over half saying it doesn’t have much impact (56 percent each). Partisan differences exist here, too, with Democrats more likely than Republicans to say that spending on global health helps in each of these areas. Still, majorities of Republicans say spending helps protect Americans from disease (68 percent), helps make people and communities in developing countries more self-sufficient (59 percent), and helps to improve the U.S. image around the world (52 percent).

| Table 3: Democrats More Likely to Say Spending Money on Improving Health in Developing Countries Helps U.S. and Other Countries | ||||

| Percent who say spending money on improving health in developing countries helps… | Total | Democrats | Independents | Republicans |

| …protect the health of Americans by preventing the spread of diseases like Ebola and Zika | 74% | 79% | 74% | 68% |

| …make people and communities in developing countries more self-sufficient | 68 | 75 | 70 | 59 |

| …improve the U.S. image around the world | 59 | 66 | 61 | 52 |

| …U.S. national security by lessening the threat of terrorism originating in developing countries | 41 | 49 | 41 | 30 |

| …the U.S. economy by improving the circumstances of people who can buy more U.S. goods | 41 | 52 | 39 | 28 |

Determining How Global Health Spending Should Be Directed

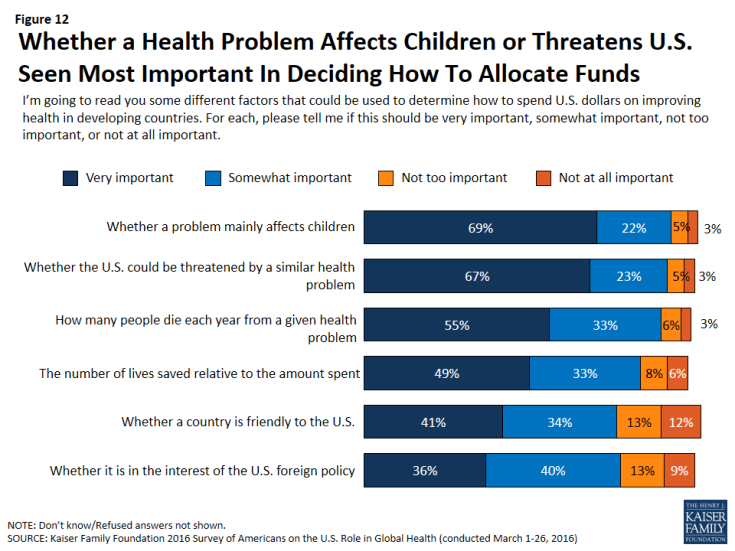

In terms of which criteria should be used to determine allocation of U.S. spending on health in developing countries, the public, regardless of party identification, ranks two factors at the top of the list: whether a problem mainly affects children, and whether the U.S. could be threatened by a similar health problem (nearly seven in ten say each of these should be “very important” in determining how U.S. dollars are spent). Roughly half also say “how many people die each year from a given health problem” (55 percent) and “the number of lives saved relative to the amount spent” (49 percent) should be very important criteria. U.S. foreign policy concerns rank lower on the list, with 41 percent placing great importance on whether a country is friendly to the U.S., and just over one-third (36 percent) saying the same about whether spending is in the interest of U.S. foreign policy.

Figure 12: Whether a Health Problem Affects Children or Threatens U.S. Seen Most Important In Deciding How To Allocate Funds

When asked how funds should be directed, a majority of the public thinks the U.S. should give money to international organizations like the Global Fund to Fight Aids, Tuberculosis and Malaria (77 percent), the United Nations and the World Health Organization (71 percent), or directly to U.S. based non-profits operating programs in developing countries (65 percent). Half of Americans also say the U.S. should give money directly to local non-profits based in developing countries. On the other side, majorities say the U.S. should not give money directly to religious or faith-based organizations (55 percent) or directly to governments in developing countries (65 percent).

Figure 13: Public Wants Funds to Go to International Organizations and U.S.-Based Non-Profits, Not Developing Country Governments

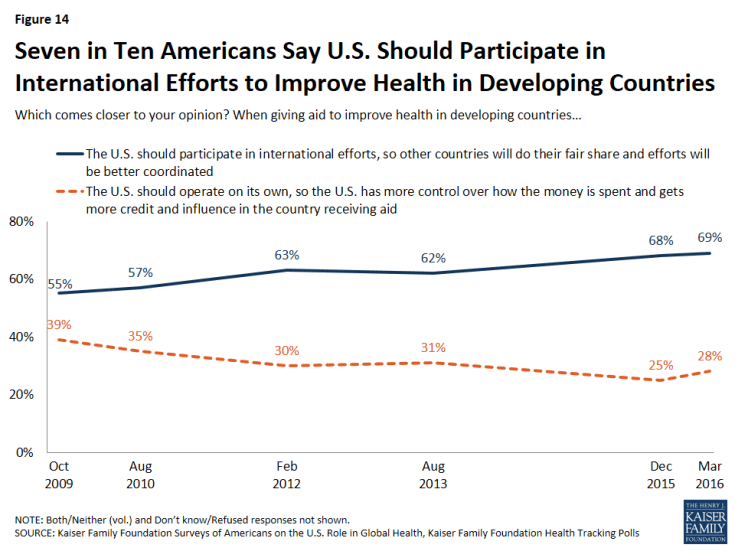

More broadly, seven in ten Americans (69 percent) want the U.S. to participate in international efforts when giving aid to improve health in developing countries, compared to 28 percent who want the U.S. to operate on its own so it has more control over how the money is spent and gets more credit and influence in the country receiving aid. The share who want the U.S. to participate in international efforts has increased steadily over the past seven years, from 55 percent in 2009 to 69 percent in 2016.

Figure 14: Seven in Ten Americans Say U.S. Should Participate in International Efforts to Improve Health in Developing Countries