Addressing Racial Equity in Vaccine Distribution

Introduction

With the possibility of a COVID-19 vaccine growing closer, increasing attention is focused on how it may be distributed, a responsibility that will largely fall to state, territorial, and local governments. States remain in varying stages of preparation, although all have submitted initial vaccine distribution plans to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Recent KFF analysis of these plans identified common themes and concerns across several key areas. However, one overarching issue to consider is how to provide equitable access to a vaccine, particularly for people of color, who are bearing the disproportionate burden of the virus and have faced longstanding disparities in health. National recommendations regarding vaccine distribution have emphasized the importance of ensuring equitable access, particularly for disproportionately affected groups, including people of color.

Preventing racial disparities in uptake of a COVID-19 vaccine will be important for helping to mitigate the disproportionate impacts of the virus for people of color and preventing widening racial health disparities going forward. Moreover, reaching high vaccination rates across individuals and communities will be key for achieving broader population immunity through a vaccine. This brief provides an overview of barriers to vaccination that disproportionately affect people of color and discusses how current national recommendations and state vaccine allocation plans address racial equity.

Barriers to Vaccination

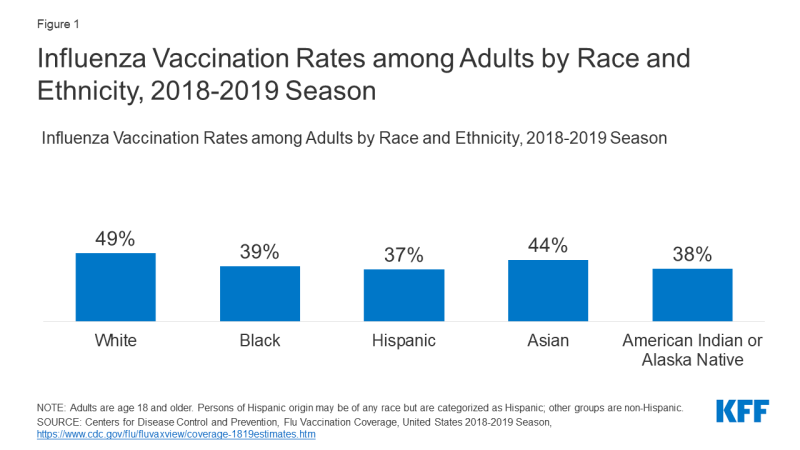

Data for existing vaccinations show people of color are less likely to be vaccinated compared to their White counterparts. For example, analysis shows that flu vaccination rates remain below the target level of 70% across racial and ethnic groups and that less than four in ten Black, Hispanic, and American Indian or Alaska Native adults were vaccinated compared to nearly half of White adults (Figure 1). Additional analyses show that this pattern persists across states and among older adults.

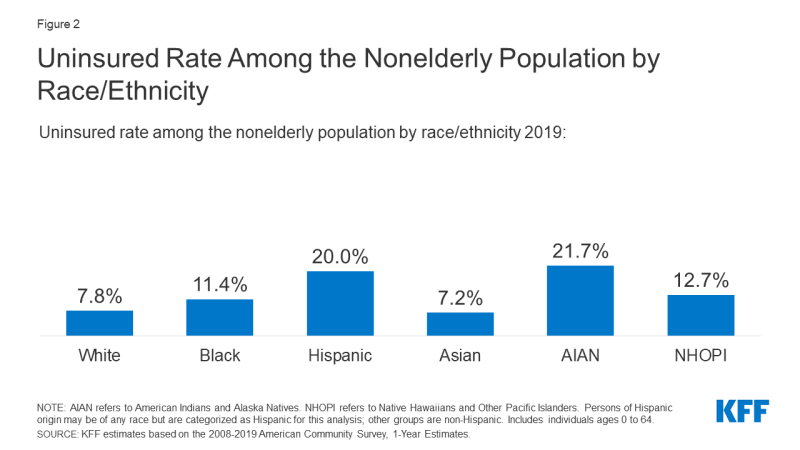

There are a range of barriers to vaccination that disproportionately affect people of color. These include access-related challenges, such as higher uninsured rates (Figure 2) and other barriers to care. Research shows that people who are uninsured have worse access to care than people who are uninsured, and many go without needed care due to cost. Although the government has indicated that the COVID-19 vaccine will be made available at no cost, it will be important for people to know how they can access it for free in order to reduce potential cost concerns as a barrier, particularly for people who are uninsured.

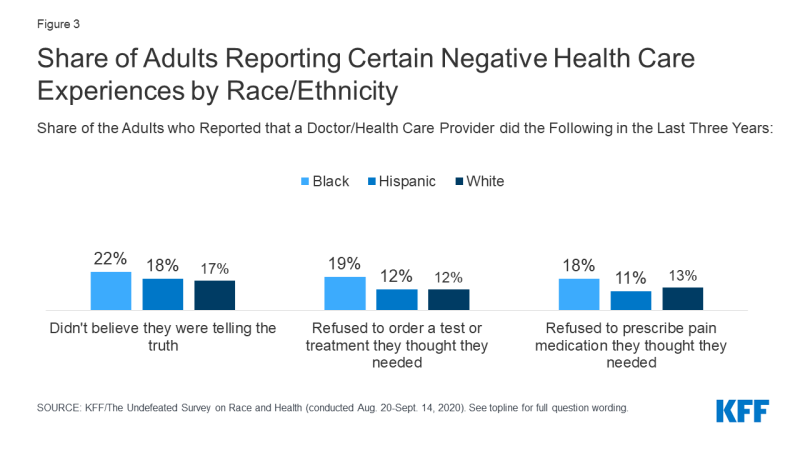

Historic and ongoing racism and discrimination also create barriers to vaccination among people of color. A recent KFF/The Undefeated survey found that Black adults are less likely than other groups to say they would get a coronavirus vaccine if it was free and determined safe by scientists, with most citing safety concerns or distrust of the health care system as reasons why they would not get the vaccine. These findings likely reflect the medical system’s historic abuse and mistreatment of people of color, particularly Black Americans, as well as ongoing experiences with racism and discrimination in health care today. For example, the survey showed that seven in ten Black adults believe race-based discrimination in health care happens very or somewhat often, and Black adults were more likely than White adults to report certain negative experience with health care providers, including feeling that a provider didn’t believe they were telling the truth, being refused a test or treatment they thought they needed, and being refused pain medication (Figure 3).

National Recommendations and State Distribution Plans

National recommendations emphasize the importance of equitable allocation of a COVID-19 vaccine for mitigating health disparities and prioritize some groups for initial access to a vaccine. The National Academies of Medicine (NAM) issued a framework for equitable allocation of a coronavirus vaccine, which identified mitigating health inequities as an underlying ethical principle. It recommended prioritizing allocation to areas identified as vulnerable through the CDC’s Social Vulnerability Index (SVI), which determines an area’s social vulnerability based on 15 social factors, including racial/ethnic distribution. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) will make final recommendations for vaccine allocation. Its ethical principles for developing recommendations include promoting justice and mitigating health inequities. ACIP has proposed prioritizing certain groups to receive initial access to the vaccine, including health care workers, long-term care facility residents, other essential workers, and older adults and adults with high-risk medical conditions. On December 1, 2020, ACIP recommended that vaccination, once authorized or approved by the FDA, initially be offered to health care workers and residents of long-term care facilities; additional recommendations are expected to follow. In contrast to the NAM and ACIP allocation approaches, HHS announced that initial allocations of the vaccine will be made to states based on their total number of adults and that states could make their own prioritization decisions within the amount allocated to them.

Prioritization of certain groups may help address disparities, but it will also be important to address equitable allocation within priority groups. Prioritization of certain groups may help to address racial disparities since people of color are disproportionately likely to be essential workers and to have high-risk underlying health conditions. However, ensuring equitable access within priority groups also will be important since racial disparities persist within them. For example, analysis shows that people of color account for the majority of COVID-19 cases and/or deaths known among health care workers, and nursing homes with relatively high shares of Black and Hispanic residents were more likely to report COVID-19 cases and deaths.

Recent KFF analysis of state vaccine distribution plans found that states vary in the in the extent to which they focus on racial equity. Just over half of the states with publicly available plans (25 of 47, or 53%) have at least one mention of incorporating racial equity into their considerations for targeting of priority populations. Some states expect to explicitly prioritize people of color, while others report using broader measures, such as the SVI (as recommended by the NAM) and/or a health equity team or framework to guide prioritization decisions. Only a subset (12 of 47, or 26%) of plans specifically mention or consider efforts to include providers that will be needed to reach diverse populations. About half of plans (23 of 47, or 49%) mention targeted efforts to reach diverse communities or underserved populations as part of their communications plans. Some states have made equity a primary guiding principle and central focus of their vaccine distribution plans. For example, states like Maine, California, Louisiana, Oregon, and Washington are embedding workgroups, task forces, or teams focused on health equity into the organizational structures designing and leading distribution plans. These states have also articulated plans to directly engage communities into their planning processes and to develop tailored communication materials that are linguistically and culturally appropriate for different populations. Prioritizing racial equity in vaccination efforts may help reduce disparities in vaccination uptake and the burden of the virus on people of color, but some have suggested that there are potential legal and ethical questions associated with any allocation plan that explicitly uses race as a criterion.

As distribution plans continue to develop, addressing access challenges and conducting effective outreach and communication can help reduce barriers to vaccination among people of color. Making the vaccine available in places and that can be easily accessed through multiple modes (e.g., car or walk-up) during hours that accommodate different work schedules and ensuring people know how to obtain the vaccine at no cost may reduce access-related barriers, particularly for people who are uninsured and may not have an established relationship with a health care provider. Moreover, prior experience with outreach and communications efforts to enroll people in coverage under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) illustrated that utilizing trusted messengers who have shared backgrounds and experiences with the people they are trying to reach and utilizing linguistically and culturally appropriate materials can be effective methods to reach diverse populations. The data and research also suggest that it will be important for providers, officials, and institutions to proactively work to earn trust with individuals and communities and directly address safety and other concerns, recognizing historic and ongoing racism and discrimination within the health care system and that some people may not want to be prioritized to receive the vaccine when it initially becomes available.

Conclusion

In sum, plans to roll out a vaccination once one becomes available are still under development and will likely continue to evolve over time. As these plans develop, it will be important to consider their implications for equitable access to the vaccine, particularly for people of color. Reducing access-related challenges and utilizing targeted and culturally appropriate and respectful outreach and communications may help reduce barriers to vaccination for people of color. Providing equitable access to a vaccine will be important for reducing the disproportionate effects of the virus for people of color, preventing widening health disparities going forward, and achieving population immunity through a vaccine.