Navigating the Maze: A Look at Health Insurance Complexities and Consumer Protections

The U.S. health insurance system has become a “complex labyrinth” for consumers to understand and navigate. Whether public or private coverage, the information needed and the hoops the average health care consumer must go through to use their health coverage effectively is itself a public policy concern, exacerbating continued access and affordability challenges. The KFF 2023 Survey of Consumer Experiences with Health Insurance found that half of insured adults have some difficulty understanding at least some aspects of their insurance. This is the first of two Issue Briefs exploring specific survey findings about gaps in understanding health coverage, highlighting problems and federal consumer protections in place today designed to bridge the gap.

This brief discusses how consumers understand what their insurance covers, what to do when coverage for care is denied, and what protections exist to ensure that information is available and coverage determinations are fair, accurate, and timely. The second brief will discuss survey findings of consumer understanding of the cost of their coverage, existing consumer protections designed to assist with understanding how much they will have to pay for a covered service, and balanced billing and other federal consumer health insurance protections.

The Labyrinth

What does a consumer need to know in order to use their health coverage effectively? The U.S. insurance system of managed care networks, utilization review, and changing coverage options can result in a complicated maze for a patient to navigate on their own. Federal and state policymakers have developed a series of incremental reforms to address understanding and transparency for consumers, but these can differ considerably based on the type of coverage, the plan the consumer chooses (if they have a choice), and sometimes, the state where they live. For private coverage in particular, the current regulatory framework is a complicated system of overlapping state and federal standards, sometimes leaving consumers to sort through a barrage of questions in order to get the care they thought was covered by their insurance.

KFF Consumer Survey Findings

The KFF 2023 Survey of Consumer Experiences with Health Insurance (“Consumer Survey”) included a nationally representative sample of 3,605 U.S. adults ages 18 and older with health insurance. The survey asked consumers about their experiences with their health insurance, including questions regarding how well enrollees understood what was covered, insurance problems that arose when enrollees tried to use their insurance, and where they sought help when they experienced insurance problems.

Understanding What is Covered

According to the 2023 KFF Consumer Survey, more than one-third (36%) of all insured adults said it was somewhat or very difficult for them to understand what their insurance will and will not cover. These shares vary by insurance type, with larger shares of those with Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplace plans (46%) and employer-sponsored plans (40%) reporting greater difficulty than those with Medicaid (28%) or Medicare (24%) (Figure 1). There were also differences in understanding certain aspects of insurance by demographic characteristics. Hispanic (36%) and White (36%) insured adults were more likely than insured Black adults (26%) to say it is somewhat or very difficult to understand what their insurance will and will not cover. Among insured adults, Hispanic adults (37%) were more likely than their Black (24%) and White (29%) counterparts to say it is at least somewhat difficult to understand their Explanation of Benefits (EOB). (An EOB is a written statement from a health insurance plan explaining what costs it will cover for medical care an enrollee has received and what the enrollee must pay, though it is not a bill). While the precise explanation for these demographic differences is not clear from the survey data, these trends are similar to those found in other research that noted health insurance literacy challenges across consumers generally, but found racial and ethnic disparities. Additionally, about three in ten insured adults ages 18-29 (30%) and 30-49 (28%) found it somewhat or very difficult to understand how to find information about which doctors, hospitals, and other providers are covered in their plan’s network, compared to 13% of insured adults ages 65 and older. (For the full list of consumer items asked about in this question, see the survey toplines.)

Educational attainment does not necessarily explain lack of understanding. The KFF Consumer Survey found that a slightly higher share of college graduates (58%) had difficulty understanding some aspect of their health insurance coverage than those without a college degree (46%). College graduates (43%) were more likely to report that it was somewhat or very difficult to understand what their health insurance will or will not cover compared to those without a college degree (31%). It is not entirely clear why education does not seem to increase understanding of insurance, though one possible explanation is that those with higher educational attainment are more likely to have private insurance (employer-sponsored insurance or Marketplace), with variable and changing insurance designs that may be more difficult to understand generally.

Areas where consumers note trouble with understanding insurance are often consistent with the top problems that consumers face with insurance. About six in ten (58%) insured adults reported experiencing a problem with their health insurance in the past year. This share is even higher (78%) among high utilizers of health care – those who had more than ten visits with a health care provider in the past year. While having a problem with health insurance does not necessarily indicate that a consumer had trouble understanding their insurance, determining what services are covered and what providers are in-network are items that cut across both topics. Several survey respondents reported problems related to using insurance that involved services or providers not covered by their plan. For example, 18% of insured adults indicated that their health insurance did not pay for a service that they thought was covered. Those with employer-sponsored (21%) and Marketplace (20%) coverage were more likely to report having this problem than those with Medicaid (12%) or Medicare (10%) (Figure 2). A somewhat larger share of insured Black (17%) and Hispanic (16%) adults reported that a doctor or hospital they needed was not covered by their insurance in the past 12 months compared to White adults (12%). Marketplace (20%) and Medicaid (19%) enrollees were more likely to encounter this problem than those with Medicare (9%) or employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) (13%). One in five (20%) insured adults ages 30-64 reported their health insurance denied or delayed a prior approval request in the past 12 months, relative to 11% of those ages 18-29 (11%) and 9% of those age 65 and older. (For the full list of consumer problems asked about in this question, see the survey toplines.)

Knowing Where To Go For Help

What actions, if any, consumers take when they encounter a problem with their health insurance might be instructive in addressing barriers to understanding coverage or best practices to assist consumers in navigating coverage questions.

Among the nearly six in ten insured adults who reported experiencing problems with their health insurance in the past 12 months, more than half (53%) said they contacted their health insurance company to resolve the problem(s) (Figure 3). A similar share (49%) said that they referred to their health insurance website or documents. Fewer said they asked a Navigator or broker for help (11%) or contacted their state Consumer Assistance Program or Ombudsman (3%).

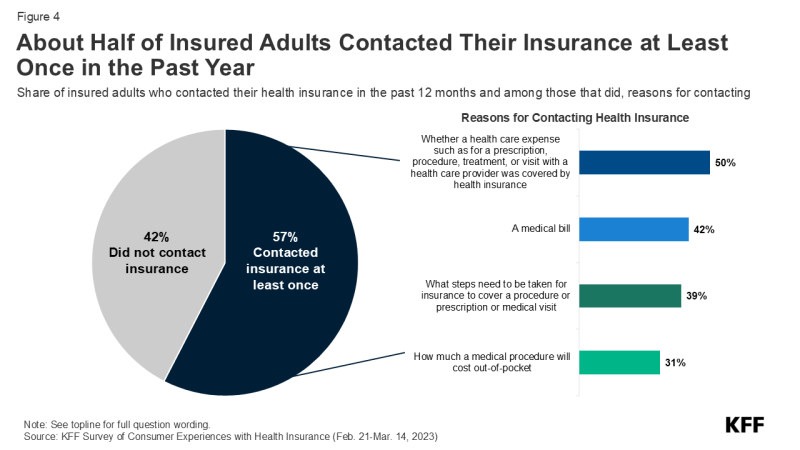

Nearly three in five (57%) of all insured adults reported contacting their insurance at least once in the past 12 months, either by phone, online, in-person, or in writing (Figure 4). Forty-two percent of insured adults did not contact their insurance company at all. Among those who did reach out to their insurance at least once, half (50%) inquired whether a health care expense (such as a prescription, procedure, treatment, or visit with a health care provider) was covered by their health insurance, making it the most common reason for contacting their insurance. Receiving a medical bill (42%) was another reason insured adults contacted their insurance, followed closely by finding out what steps needed to be taken for their insurance to cover a prescription, procedure, or medical visit (39%). Fewer (31%) contacted their insurance at least once in the past year to find out how much a medical procedure would cost out-of-pocket.

Most insured adults are unaware that they have the legal right to appeal to a government agency or independent medical expert if their health insurance refuses to cover needed medical services (Figure 5). Those with public insurance are more likely than those with private insurance to be aware of this right. Just one-third (34%) of those with ESI or Marketplace coverage know they have this right, compared to 58% of Medicare beneficiaries and 45% of those with Medicaid. Further, just one in ten (10%) insured adults who experienced a problem with their health insurance in the past year filed a complaint with their health insurance company (data not shown). This share is similar across all four coverage types.

Three-quarters (76%) of adults with insurance reported not knowing what government agency they would call for help if they wanted to. Adults with ESI (83%) or Marketplace (81%) coverage were more likely to report that they did not know which government agency to contact compared to Medicare (61%) and Medicaid (70%) enrollees. Among insured adults with ESI or Marketplace coverage who reported that they did know which government agency they would contact, 15% of those with ESI and 6% of those with Marketplace coverage reported that they would reach out to their state insurance department/commission(er), the lead agency that is responsible for regulating non-group health coverage and insured group coverage. No one reported that they would contact the Department of Labor (DOL), the government agency that regulates health plans sponsored by private employers, including self-insured employer health plans.

Federal Consumer Protections Seek to Address Barriers to Understanding Coverage

Many federal reforms have focused on providing consumers with better information about their plan, standardizing and simplifying information, and making sure notice is provided of key design features and reforms. While public programs such as Medicare and Medicaid also provide consumer protections, this section focuses primarily on federal protections for those with private health insurance coverage (individual and employer-sponsored).

Understanding What is Covered

The ability to access accurate and easy-to-understand written information has long been a core consumer protection. Below is the landscape of written materials a consumer can access to get information to understand their coverage. Figure 6 is a snapshot of some key consumer protections for those with private insurance.

Coverage documents and summaries: All forms of coverage, whether Medicare, Medicaid, or private insurance available through an employer or a health insurance Marketplace, are required as a form of consumer protection to provide information about benefits and coverage, with varying content requirements, formats, and frequency of updates. Although there are fewer required standardized information formats across private coverage than in public programs such as Medicare, the ACA ushered in a standardized template across most private insurance through the Summary of Benefits and Coverage (SBC), with information on key coverage items and exclusions, cost-sharing, and rules for accessing care. All ACA-compliant plans in the individual and group insurance market and all employer-sponsored plans must provide consumers with an SBC.

More detailed coverage documents can extend to one hundred written pages or more; however, electronic formats and machine-readable files may make it easier to access information for those with the technology and ability to research this information. Examples in the private insurance market include state-regulated insurance documents (including Marketplace plans) sometimes called Certificates of Coverage, or plan documents and Summary Plan Descriptions that set out benefits for those in employer group health plans covered by ERISA.

Provider directories and formularies: Provider directories and formularies allow consumers to see what providers and medications are covered by their insurance. While these items might be easy to access online, several research studies have found that provider directories are often inaccurate. Federal consumer protections across public and private coverage include various features designed to ensure that plans maintain more accurate and up-to-date information. In some cases, these protections also require plans to meet minimum network adequacy standards and test that accuracy through “secret shopper” compliance programs.

Private coverage protections include the No Surprises Act (NSA) requirements, which apply to all private insurance (including employer coverage) and set standards for both plans and in-network providers to ensure accurate provider directory information. Consumers must be reimbursed for cost sharing in excess of in-network amounts when they rely on inaccurate directory information indicating that a provider was in-network. Plans must also continue to cover care from certain providers for a limited period of time after they leave an insurance network.

There is little research on prescription drug formulary accuracy and how consumers determine what medications are covered, but some public programs have model formulary templates to make it easier for consumers to review. There are no federal standards for private employer plans for formulary format, accuracy, and usability.

Consumer notice of rights, disclaimers, and marketing restrictions: Nearly every new consumer protection includes a requirement on an employer or insurance plan and/or provider to notify patients that the protection exists. For example, the NSA requires providers and facilities, as well as plans, to provide patients with information about the NSA’s balanced billing protections. Other federal reforms are meant to alert consumers about aspects of their coverage that might easily be misunderstood with a clear warning or disclaimer. For instance, federal rules for short-term limited duration coverage require a prominent statement that this coverage is “NOT COMPREHENSIVE COVERAGE.” This federally required warning on plan materials, as well as one for fixed indemnity plans, has been the subject of recent litigation questioning the need for and validity of these disclaimers. Another federal agency, the Federal Trade Commission, enforces protections against unfair or deceptive marketing or advertising to consumers that, for example, misrepresents certain limited coverage arrangements as comprehensive health insurance. Several recent investigations have been in collaboration with the federal health insurance agency Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

Information about coverage determinations and appeals: Even if a consumer has located written information that an item, service, or provider visit is covered by their insurance, they could still face a denial of coverage (e.g., because the plan does not deem the care “medically necessary”), which can create frustrating hurdles for consumers. Medicare and Medicaid have longstanding processes for claims review and appeals. Private coverage also includes certain protections including:

- Processes for reviewing claims: All private insurers and employer plans must ensure a “full and fair” review of enrollee claims. In addition, the ACA includes a “transparency in coverage” provision that requires all non-grandfathered private health plans to provide information and statistics about plan practices to the public and to federal and state agencies, including data on claims payment policies and procedures and the number of claims denied.

- Prior authorization: The longstanding practice of health plans requiring patients to obtain approval for a health care service or medication before the care is provided has received renewed scrutiny in recent years. New federal protections issued in 2024 and effective in 2027 streamline the process and require aggregate reporting of the number of claims denials for federal Marketplace plans as well as Medicare Advantage and Medicaid managed care organizations.

- Information about why a claim was denied: Health insurers and employer plans must clearly disclose to consumers the reason(s) their claim was denied, provide information on their right to appeal the decision, and include the name of any Consumer Assistance Program (CAP) in their state. Consumers can also request more specific information from their plan about the decision (e.g., policy provisions related to the denied claim, names of experts consulted for decision).

- Internal appeal to the plan: If a consumer disagrees with a denied claim from their health plan, they can file an internal appeal with their plan. Plans are required to inform consumers of their appeal decision within 30 days for a service not yet received, within 60 days for a service that was already administered, and within 72 hours in urgent medical cases (sometimes less depending on the situation).

- External independent review: Consumers whose claims denial is upheld at internal appeal may have the right to an external review by an entity independent of the plan for certain types of claims.

Language assistance and information in alternative formats: Requirements to provide some form of language assistance and auxiliary aids to help with understanding coverage exist across most forms of coverage. Private employer plans have long been required to offer assistance in a non-English language where the plan covers a specific percentage of participants in the plan who are “only literate” in the same non-English language. The ACA requires that the SBC and certain claims and appeal notices be provided in a “culturally and linguistically appropriate manner” by individual and group insurers and self-insured employer plans. This could include items such as oral language services and a notice in a certain non-English language provided to enrollees upon request if they live in a county where 10% or more of the population is literate only in the same non-English language.

Separate language access standards apply to recipients of federal financial assistance, programs that HHS administers, and entities established under the ACA, such as health insurance Marketplaces. As a result, most private insurers participating in public and private insurance programs (including some who also provide insurance or administrative services to employer-sponsored coverage) must comply.

Effective communication for individuals with disabilities is also required under the ACA. Current regulations likely extend to information about health insurance coverage through the use of “auxiliary aids” for individuals with disabilities, such as sign language interpreters onsite or by video. Electronic information technology used to provide information about health coverage to enrollees must also be accessible for individuals with disabilities unless doing so creates an undue burden or fundamentally alters the program. Similar access standards for persons with disabilities might also apply to those who sponsor coverage and are also subject to the Americans with Disabilities Act or the Rehabilitation Act.

Direct Assistance

Some consumers may seek one-on-one communication to understand technical details in an insurance coverage document, to get more information about plan or provider policies and procedures, or to navigate the claims appeal process. The 2023 KFF Consumer Survey indicates that more insured adults reach out to their insurance company when encountering a problem than look to written plan material for resolution. Ensuring that consumers have access to effective and impartial one-on-one help has been the subject of federal consumer protection requirements. Figure 7 is a snapshot of key channels for direct consumer assistance.

Customer service options: Private insurers generally make certain customer services available to enrollees. Customer service provided by health plans is commonly offered via call centers, electronic messaging platforms, and increasingly, virtual chatbots. States may have specific customer service requirements for insurers selling state-regulated plans, such as call center wait time standards or staffing a minimum number of customer service representatives.

Health insurance marketplaces are required to provide consumer tools. Healthcare.gov operates a toll-free call center 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, for consumers with questions related to the federal health insurance Marketplace. The ACA also requires all state-based marketplaces to provide a live call center during their hours of operation. Call center representatives must assist consumers with inquiries related to qualified health plans, enrollment, cost-sharing reductions, and advanced premium tax credits (APTCs). Beyond relying just on insurers to provide this information, Congress also created the Navigator grant program to give enrollees access to an additional source of information from organizations other than health insurers to help navigate Marketplace coverage.

For those with private employer-sponsored coverage, there is no specific requirement under federal law to provide direct assistance to help covered employees and their families. Human resources staff sometimes perform this role if a consumer is unable to get answers from customer service personnel available from their insurer or third-party administrator. Some firms contract with third-party vendors to provide patient navigation or “concierge” services that help enrollees navigate plan services and advocate for enrollees as patients, among other services. According to the KFF Employer Health Benefits Survey, in 2024, 29% of firms with 200 or more employees that offered health benefits contracted with a vendor to provide “concierge” services to their enrollees. Separately, the DOL’s Employee Benefits Security Administration (EBSA) operates a toll-free phone number and an online message platform for consumers with questions or concerns related to federal legal requirements, obtaining health plan documents, and assistance getting claims paid.

Funding to state and other entities providing direct assistance: Before the ACA, some states had already established their own Consumer Assistance Programs (CAPs) or health insurance ombudsman programs to help all consumers explore coverage options or assist in resolving problems with their health insurance. Federal CAP grants as part of the ACA allowed for the improvement of existing programs and the creation of new CAPs in other states. In addition to assisting with consumer education and enrollment, the ACA listed one of the duties of CAPs as “assisting with the filing of complaints and appeals… of group health plans…and providing information about the external appeal process.” However, CAPs still operating today have not been supported by federal grant funding since 2012, effectively eliminating the only federally-funded assistance program available to consumers with employer coverage. Several have ceased operations due to lack of funding.

As referenced above, in addition to CAPs, Navigators were established under the ACA as a program to provide direct assistance to consumers in both HealthCare.gov states and in states that operate their own marketplace. Navigators offer support by conducting public education and outreach, helping consumers apply for financial assistance, assisting with enrollment and post-enrollment issues, and providing fair and impartial information about health plan options. Navigators cannot be insurers, nor can they receive any direct or indirect payment from an insurer. These programs in HealthCare.gov states are funded by federal grants, the amounts of which have fluctuated over the years depending on which political party is in power. In February 2025, the Trump administration announced it would cut funding for the Navigator program from its current $100 million to $10 million for 2026.

Standards for health insurance agents and brokers: Agents and (web)brokers play a large role in selling coverage in the individual and group insurance markets and can assist consumers in understanding their health insurance options and costs. While most agents and brokers are certified and regulated at the state level, federal requirements for those agents and brokers involved with Marketplace plans are meant to protect consumers from fraudulent activity and misleading information from agents and brokers, and to make sure consumers are aware of how they are paid and the possibility of conflicts of interest in steering consumers to certain products that financially benefit the agent/broker/web broker. Federal law also requires agents, brokers, and other service providers that work with private employer plans to disclose to employers how they are paid.

Looking forward

KFF 2023 Consumer Survey findings about how consumers understand and navigate the health insurance system reveal frustrating hurdles to determine what items and services and what providers are covered by their insurance. It presents the question of whether we have a system that is impossible for a consumer to navigate alone, leaving consumers vulnerable to exploitation and confusion as they are caught in the middle of health plan and provider interests and arbitrary boundaries of authority between state and federal agencies. Coming out of an election widely viewed to have turned on concerns about the economy, including health care costs, and following public outrage against insurers following the killing of the United Healthcare CEO at the end of 2024, expect that health care consumer issues will not go away, but perhaps will shift focus to include:

Use of digital technology such as artificial intelligence (AI) to assist consumers: Though imperfect and with some pitfalls, digital technology, including AI, can help consumers navigate the complexities of health insurance. These tools are increasingly being promoted to both companies and individuals and in 2024, nearly two-thirds (64%) of adults say they have used or interacted with AI. AI tools can be appealing to consumers looking for answers to health insurance-related questions without the need to make a phone call, wait on hold, or read through plan documents, and are often available 24/7. From guiding consumers through the insurance claims process, including filing appeals, to helping determine whether a plan that applies coinsurance or copayments for their prescription drugs will meet their needs, and identifying in-network doctors near a patient’s home, these tools have the potential to transform the ways in which people seek health information.

However, AI has also been in the spotlight following investigations and litigation in recent years related to health plans’ use of these tools in making coverage determinations, such as for prior authorization requests and in the claims review process. Much of the existing research and criticisms related to the use of AI in health care more broadly, such as clinical decision-making and claims processing, feature overarching concerns related to their accuracy, reliability, confidentiality, and accessibility that could also apply to consumers using AI and other digital technology to navigate their health insurance.

Patient input in coverage practices: Broader and different mechanisms to gather information about consumer experiences in real time could assist in determining the most pressing concerns for patients and engage more consumers in policy discussions about what structural changes and protections are most needed and impactful for them. One of the largest health insurers recently announced changes aimed at improving the patient experience in using their coverage, expanding consumer support, and improving transparency. Employers are making changes to better oversee and understand their benefit programs and provide consumer input and navigation services as plan sponsors face real scrutiny for the first time under longstanding federal fiduciary requirements.

For the federal government, while deregulation across health care, as well as federal agency upheaval, is likely to be the focus in the coming years, the Trump administration will be tasked with implementing key provisions of the No Surprises Act, which he signed into law, that requires upfront information about what services cost and more accurate provider directories. The Trump administration has already issued an Executive Order for agencies to “rapidly implement” price transparency regulations.

Promoting other forms of coverage: A reaction to the health insurance labyrinth has some promoting mechanisms to move away from traditional insurance to direct payment alternatives such as direct primary care arrangements and account-based arrangements where consumers use dollars available in a health savings account or other type of account to purchase care. The pros and cons of these arrangements will be up for debate, as well as whether consumers—especially those with lower incomes and/or chronic illnesses—are well served by the financial and coverage limitations that may be part of these arrangements, including existing problems with the price transparency data available to them and the rising cost of care due to provider consolidation. Patients might be faced with a different set of understanding challenges under these arrangements.

Understanding how health coverage works, what services are covered and by whom, and what rights consumers have is one piece of the health insurance labyrinth. The second brief in this series on consumer understanding will focus on the cost-related aspects and challenges of health insurance and health care.

This work was supported in part by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The views and analysis contained here do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism.