What We Do and Don’t Know About Recent Trends in Health Insurance Coverage in the US

Rachel Garfield and Jennifer Tolbert

Published:

The usually highly anticipated release of the Census Bureau’s annual health insurance estimates, which occurred this past Tuesday for 2019 data, felt a bit different this year. While researchers and policymakers are accustomed to dealing with somewhat outdated data from federal surveys, the unprecedented social and economic changes that have occurred since the data were collected amplified the time lag and made the estimates seem even older than in past years. Current data on insurance coverage in the US is needed to design an adequate response to the pandemic and economic crisis, but the 2019 estimates still provide a useful baseline for interpreting what’s happening during the pandemic.

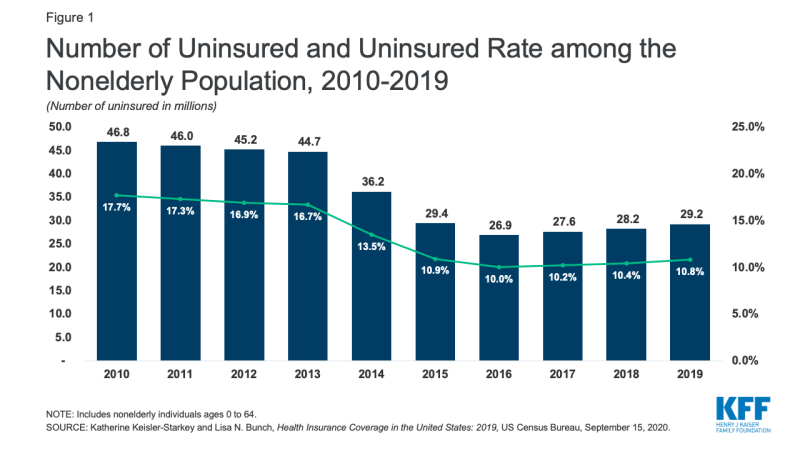

Prior to the pandemic, the uninsured rate had been increasing incrementally for several years despite an improving economy. After historic declines in the number of uninsured people and the uninsured rate following the adoption and implementation of the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA), resulting in nearly 20 million more people covered through 2016, the number and rate of nonelderly uninsured people began to increase in 2017. The uninsured count grew from 26.7 million (10.0%) in 2016 to 27.6 million (10.2%) in 2017, 28.2 million (10.4%) in 2018, and, as was announced this week, 29.2 million (10.8%) in 2019 (Figure 1).

The 2.3 million person growth in the number of uninsured occurred despite improvements in several household economic measures, including median household income, earnings, and poverty and despite small gains in employer-based coverage over this period, which were offset by declines in Medicaid and direct purchase coverage. This pattern likely reflects a combination of factors, including rollback of outreach and enrollment efforts for ACA coverage, changes to Medicaid renewal processes, public charge policies, and elimination of the individual mandate penalty for health coverage. Notably, recent declines in coverage have occurred among both adults and children.

Because most people in the US still get their health coverage as a fringe benefit of a job, the recent economic downturn may disrupt coverage for millions of people. The economic fallout of the coronavirus pandemic has led to historic levels of job loss, with over 50 million people filing for unemployment insurance benefits since March 21st. Prior to the pandemic, nearly six in ten nonelderly people in the US received their health coverage through their job or a family member’s job. Early KFF estimates of the implications of job loss found that nearly 27 million people were at risk of losing employer-sponsored health coverage due to job loss. Other modeled estimates similarly predict millions losing employer health coverage, though the scale varies somewhat. Many of these people may have retained their coverage, at least in the short term, under furlough agreements or employers continuing benefits after layoffs. Indeed, recent KFF analysis of enrollment in the fully-insured group market found that enrollment in that market declined by just 1.3% from March to June 2020. Employer-based insurance losses could mount if unemployment remains high.

The availability of health coverage through the Affordable Care Act during this economic downturn means people losing their coverage have other options, but policy actions to scale back the ACA may mean people are unaware of or have difficulty accessing that coverage. Expanded coverage through Medicaid in the 37 states that have implemented the Medicaid expansion along with the availability of subsidized and unsubsidized coverage through the Marketplaces will enable many people losing their job-based insurance to retain health coverage. Following enrollment declines in 2018 and 2019, recent data indicate Medicaid enrollment increased by 2.3 million or 3.2% from February 2020 to May 2020. Additionally, as of May 2020, enrollment data reveal nearly 500,000 people had gained Marketplace coverage through a special enrollment period (SEP), in most cases due to the loss of job-based coverage. The number of people gaining Marketplace coverage through a SEP in April 2020 was up 139% compared to April 2019 and up 43% in May 2020 compared to May 2019. While millions of people are gaining coverage through Medicaid and the Marketplaces, reductions in outreach and enrollment assistance have reduced the availability of on-the-ground assistance for consumers who have lost coverage meaning many others may not be enrolling because they are not aware this coverage is available or don’t know how to enroll.

The pandemic has disrupted not only people’s health coverage but also the ability of federal surveys to measure coverage. Understanding real-time changes in insurance coverage is a key input into policy actions to address the implications of the pandemic on people’s health and well-being. However, to date, limited data is available on this topic. Large national surveys—those typically used as the basis for such information—are lagged, with the most recent data reflecting the first quarter of 2020, just prior to the pandemic. Many real-time surveys have faced challenges of high rates of survey nonresponse (not responding to the survey at all) particularly among populations most likely affected by the economic downturn, or unusually high rates of item nonresponse (skipping particular survey questions). In the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, designed to provide quick turnaround data on issues related to the pandemic, most weeks had a larger number of responses of “don’t know” or “did not report” to the question about health coverage than the number of uninsured. These measurement challenges may reflect people’s confusion about their current coverage amidst layoffs and job uncertainty or operational challenges in administering surveys that ask about health coverage (e.g., inability to conduct in person surveys).

While current survey data is limited and administrative and claims data are showing only moderate shifts in coverage, it is likely that large shifts in health coverage in the US are underway or imminent given loss of employment in recent months. It is possible that many of the people in families experiencing job loss were already uninsured, but given that prior to the pandemic the uninsured population in a family with a full-time worker totaled 20.2 million, there are still people among the 50 million who filed for unemployment benefits that may lose their employer coverage if they do not regain their jobs. In the midst of a health and economic crisis, the gap in real-time data to assess changes in health coverage poses a challenge.