The Proliferation of State Actions Limiting Youth Access to Gender Affirming Care

Lindsey Dawson and Jennifer Kates

Published:

Just as LGBTQ identity is increasing in the U.S. and national support for same-sex marriage is holding at an all-time high, states are enacting a range of new laws and policies aimed at limiting LGBTQ people’s access to social institutions in domains such as school and health care. Transgender people’s rights, in particular, have become a divisive partisan issue that is already playing a role in discourse and debate in the 2024 election.

Gender Affirming Care (GAC)

Gender affirming care is a model of care which includes a spectrum of “medical, surgical, mental health, and non-medical services for transgender and nonbinary people” aimed at affirming and supporting an individual’s gender identity. Gender affirmation is highly individualized. Not all trans people seek the same types of gender affirming care or services and some people choose not to use medical services as a part of their transition.

One area that has received considerable attention is young people’s access to gender affirming care. Gender affirming care services are widely considered medically necessary best practices for those that need them, including for youth. Virtually all major U.S. medical associations support youth access to gender affirming care, including the American Medical Association, American Academy of Pediatrics, and the American Psychological Association, among others. In particular, these groups point to the evidence demonstrating that medically necessary gender affirming care enhances mental health outcomes for transgender youth, including by reducing suicidal ideation. Professional guidance for gender affirming care, including for young people, is provided by the Endocrine Society and the World Professional Association for Transgender Health, bodies that also support access to this treatment model. Despite the evidence around the role gender affirming care can play in promoting well-being and support from the medical community, those seeking to enact state restrictions to this care contend that such policies are necessary to “protect children” and that the potential medical risks linked to gender-affirming care outweigh any benefits. Notably, not all trans people choose to incorporate the medical services these policies prohibit as part of their transition and instead focus on social transition. Further, while the number of young trans people using puberty blockers or hormone therapy has increased modestly in recent years, overall number of those using these prescriptions remains fairly low and multiple studies have shown gender affirming surgery is rare among youth.

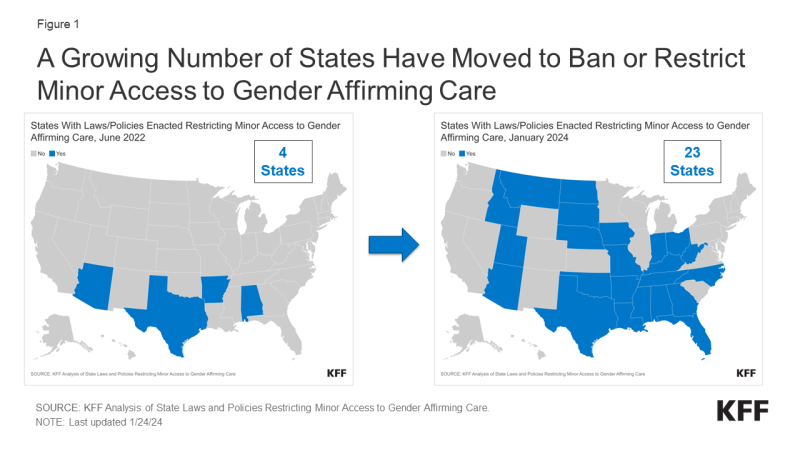

Over the past 18 months, there has been a rapid increase in the number of states that have enacted laws and other policies that prohibit or restrict minor access to gender affirming care. Our new tracker, provides a regularly updated overview of state policy developments aimed at restricting minor access to gender affirming care as well as the litigation challenging it. This policy watch summarizes findings as of January 30, 2024.

Current Status

- In less than two years, the number of states with laws or policies limiting minor access to gender affirming care has increased more than five-fold, climbing from just four states in June 2022 (AL, AR, TX, AZ) to 23 states by January 2024 (AL, AR, AZ, FL, GA, IA, ID, IN, KY, LA, MO, MS, MT, NC, ND, NE, OH, OK, SD, TN, TX, UT, WV).

Figure 1: A Growing Number of States Have Moved to Ban or Restrict Minor Access to Gender Affirming Care

- As the number of states enacting such policies increases so do the number of trans youth potentially impacted. The 23 states with laws and/or policies limiting youth access to gender affirming care are home to an estimated 38% of young trans people between the ages of 13-17.

- Of the 23 states with laws/policies restricting youth access to gender affirming care: 17 are currently in effect in full. Four are temporarily blocked in full or in part and one is permanently blocked in court, though an appeal is pending. The law in Ohio does not go into effect until April 2024. (See Litigation section for additional discussion of legal activity in this area.)

- While all of the laws/policies examined seek to limit or prohibit access to key gender affirming care services for young people, they range in their complexity. Some are comparatively limited (e.g. banning only surgical care, which is rare among youth), while others are more far reaching in terms of their scope of prohibitions, penalties, and individuals impacted.

Other Groups Impacted By State Laws/Policies

Although these laws/policies primarily center on restricting minor access to gender-affirming care, many also include provisions impacting other groups that are found to provide or otherwise support such youth access, as follows:

Medical Providers

- Nearly all states (21 of the 23) include specific provisions with penalties for providers (exceptions are AZ and WV).

- 20 states include either professional or civil penalties (AR, FL, GA, IA, ID, IN, KY, LA, MO, MS, MT, NC, ND, NE, OH, OK, SD, TN, TX, UT). Professional penalties may include a loss of a medical license or referral to medical licensing boards for further action.

- 5 states (AL, FL, ID, ND, OK) include felony penalties for providers.

- 8 states (AR, FL, IA, IN, MS, MT, OH, UT) include provisions prohibiting providers from offering minors referrals for or otherwise “aiding and abetting” access to gender affirming care.

Parents

- 4 states (FL, MS, OH, TX) include provisions directed at parents or guardians. For example, Florida’s law, which affects parents most directly, modifies state custody laws to permit the state to take physical custody (or modify another state’s custody determination) of the child, if a child present in the state is “at risk of or is being subject to” gender affirming care. A Texas directive defines certain gender affirming services as child abuse calling for investigation of and penalties for parents supporting access to care, which could include the removal of their children.

Teachers, counselors, and other officials

- 4 States (AL, MS, MT, TX) include laws/policies that impact school officials such as teachers and counselors, among others. The Alabama law prohibits nurses, counselors, teachers, principals, and other administrative school officials from “encouraging” or “coercing” minors from withholding that their gender identity is different from their sex assigned at birth from their parent/guardian. Because the Mississippi law prohibits “aiding and abetting” youth access to gender affirming care by any person, teachers and other school officials could be implicated. Montana prohibits any state official, such as a school counselor, from providing or “promoting” gender affirming care. As mentioned above, Texas’s definition of certain gender affirming services as child abuse implicates a range of professionals such as teachers who are mandated reporters.

Transgender Adults

- In addition to prohibiting minor access to gender affirming care, 7 states (AL, AR, FL, MO, MS, NC, NE) limit adult access in some way. These include provisions that would, for example, allow private health plans, Medicaid, and/or correctional facilities to exclude all gender affirming care coverage and/or prohibit them from providing such services; prohibit the use of federal funds for gender affirming care; require informed consent practices beyond those typical required in medical practice; and render gender affirming services non-tax deductible under state income tax law or due to some states definition of minors, those who are 18 years old.

Exceptions

- Six (6) states provide exceptions, allowing access to this care in certain circumstances (GA, FL, OH, NC, NE, ND), including some limiting access to minors who were receiving these services prior to the law’s enactment (e.g. NC, ND, OH). Nebraska has a broader process available but it includes strict requirements to qualify for exceptions for individuals, families, and providers. Another six states (LA, IN, KY, OK, SD, and TX) that allow for these exceptions do so with a requirement or expectation that the minor will taper their use and be “weaned” from treatment within a certain time frame.

- Notably,despite the prohibitions around gender affirming care for trans youth, all 23 states allow the same services prohibited under the law/policy to be used in other medical circumstances (e.g. when they are prescribed to address “precocious puberty” or chromosomal sex differences, among other “conditions”).

Litigation

- Just as the number of states enacting such policies has increased, so has the number of lawsuits challenging them. The majority of states with laws/policies in place (16 or 23) are facing legal challenges.

Looking Ahead

State policy making that limits youth access to gender affirming care can be viewed in a broader context of other actions states have taken to restrict young trans people’s access to social institutions. For example, states have enacted so called “bathroom bills,” “don’t say gay bills,” requirements that schools notify parents if minors use gender pronouns not reflective with their sex assigned at birth, and laws that limit transgender students’ access to sport. (The Movement Advancement Project tracks a range of these policy areas, including youth access to gender affirming care.) Conversely, other states have made efforts to secure trans people’s access to health care (including adults) by creating coverage requirements for private insurance and Medicaid and enacting shield laws to protect patients/providers seeking care when it is prohibited in their home state.

LGBTQ rights, especially those impacting young people, are shaping up to be a major issue in the 2024 election and are being debated heavily at the state and local level, as evidenced by the proliferation of laws and policies seeking to limit youth access to gender affirming care.

Looking ahead, it will be important to monitor whether states continue to enact these policies, how litigation takes shape, and whether the Supreme Court elects to take the cases that it has been petitioned to hear. These laws and policies have political implications, but importantly also have the potential to affect the wellbeing of young trans people and LGBTQ people more broadly, with implications as well for health care providers, parents, and teachers.