Stay-At-Home Orders to Fight COVID-19 in the United States: The Risks of a Scattershot Approach

Jennifer Kates, Josh Michaud, and Jennifer Tolbert

Published:

By late-February, it became increasingly clear that sustained community transmission of coronavirus had taken hold in parts of the United States, particularly on the West Coast and, soon after, the New York City region. With little testing available and no significant federal response beyond instituting international travel restrictions at the time (the President downplayed the threat of COVID-19 well into March), some jurisdictions took matters into their own hands and began implementing social distancing measures.

On March 4, King County officials in Washington State first recommended that certain vulnerable groups (including people over 60 years old and those with underlying health conditions) stay home, businesses allow more telecommuting options, and the cancellation or postponement of large public events; school closures began in parts of the state within a couple of days. On March 6, San Francisco similarly warned vulnerable residents to avoid outings and larger groups, businesses to suspend non-essential travel and consider telecommuting, and cancelation of all non-essential large events, and the city began restricting event size a few days later. By March 16, six Bay Area counties became the first in the nation to announce shelter-in-place orders and on March 19, the State of California became the first to mandate a state-wide order.

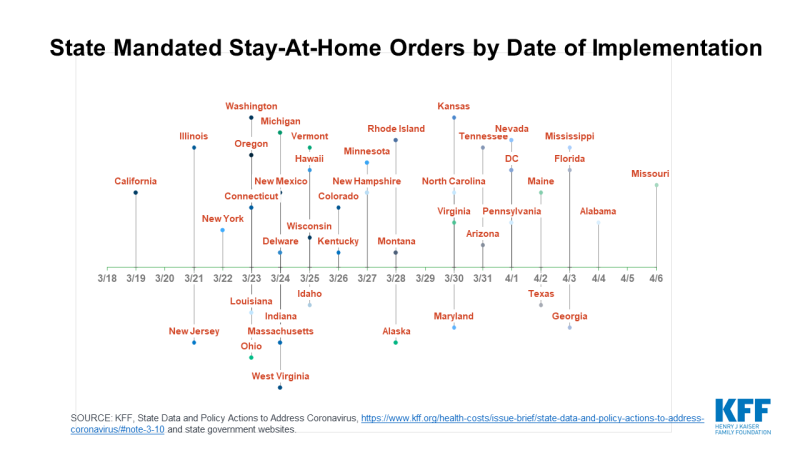

Since then, additional states and communities across the country began implementing mandatory stay-at-home orders (and other social distancing measures, including school closures, many of which began state-wide on March 16, and closing non-essential businesses). But, with conflicting messages from the federal government and a lack of clear guidelines, states have not been on the same page, and implementation has been scattershot at best. In some cases, contiguous states have had different policies (such as South Carolina, which has no mandate and North Carolina which does). Moreover, in some states (including those with rapidly rising caseloads), Governors resisted issuing state-wide orders, leaving decisions up to local jurisdictions, creating confusion and concern and prompting calls from local officials and public health experts for state-wide action. This was the case, for example, in Florida, Georgia, and Texas until recently and remains so in a handful of other states. It’s hard to see how a highly infectious virus is going to pay very close attention to different policies across states, let alone within them. Indeed, new data shows that there was more travel in counties without such orders.

There have been some exceptions to this. In recognition of regional commuter and other patterns, Washington DC, Virginia and Maryland have operated much more in lockstep (although there have been some differences). All three implemented similar voluntary state-at-home orders during the third week of March and a coordinated mandatory one announced on March 30. In the Mayor of DC’s voicemail message to residents, she specifically said, “pandemics don’t care about borders. That’s why we are all doing the same thing and we are telling everyone in the Capital Region – DC, Maryland, and Virginia – please stay home.”

Still, by March 25, when there were more than 12,000 cases reported in the U.S., only 19 states had mandatory stay-at-home orders in effect. An additional 11 instituted orders taking effect by March 30. The recent announcement by the White House that federal social distancing guidelines would be extended through at least April 30, an acknowledgment that the outbreak is significantly worse than it had previously suggested, is likely to lead to more uniformity across states. Already, since the announcement, several additional states have announced their intention to implement stay-at-home orders. Many states have gone well beyond the White House guidance, which is a recommendation, not a requirement. At the time of this writing, 9 states had not yet issued state-wide orders.

It is still too early to know whether those states that implemented such measures earlier will see better outcomes (although data from both Seattle and San Francisco suggest that they are working) or whether differential implementation across the country and within states will affect the success of all communities, as the virus may continue to spread across geographic borders it doesn’t recognize. At the very least, this scattershot approach can result in ongoing transmission in one state or community, even as transmission is interrupted in a neighboring area. This could extend the period of spread for the U.S. overall and prolong the need for social distancing in much of the country. We are engaged in a “natural experiment” of differing approaches to the epidemic on a massive scale, and we are likely to see over the coming weeks what the consequences of that will be.

| Statewide Stay-at-Home Orders | ||

| State | Date Announced | Effective Date |

| Alabama | April 3 | April 4 |

| Alaska | March 27 | March 28 |

| Arizona | March 30 | March 31 |

| Arkansas | – | – |

| California | March 19 | March 19 |

| Colorado | March 26 | March 26 |

| Connecticut | March 20 | March 23 |

| Delaware | March 22 | March 24 |

| District of Columbia | March 30 | April 1 |

| Florida | April 1 | April 3 |

| Georgia | April 2 | April 3 |

| Hawaii | March 23 | March 25 |

| Idaho | March 25 | March 25 |

| Illinois | March 20 | March 21 |

| Indiana | March 23 | March 24 |

| Iowa | – | – |

| Kansas | March 28 | March 30 |

| Kentucky | March 22 | March 26 |

| Louisiana | March 22 | March 23 |

| Maine | March 31 | April 2 |

| Maryland | March 30 | March 30 |

| Massachusetts | March 23 | March 24 |

| Michigan | March 23 | March 24 |

| Minnesota | March 25 | March 27 |

| Mississippi | March 31 | April 3 |

| Missouri | April 3 | April 6 |

| Montana | March 26 | March 28 |

| Nebraska | – | – |

| Nevada | April 1 | April 1 |

| New Hampshire | March 26 | March 27 |

| New Jersey | March 20 | March 21 |

| New Mexico | March 23 | March 24 |

| New York | March 20 | March 22 |

| North Carolina | March 27 | March 30 |

| North Dakota | – | – |

| Ohio | March 22 | March 23 |

| Oklahoma | – | – |

| Oregon | March 23 | March 23 |

| Pennsylvania | March 23 | April 1 |

| Rhode Island | March 28 | March 28 |

| South Carolina | – | – |

| South Dakota | – | – |

| Tennessee | March 30 | March 31 |

| Texas | March 31 | April 2 |

| Utah | – | – |

| Vermont | March 24 | March 24 |

| Virginia | March 30 | March 30 |

| Washington | March 23 | March 23 |

| West Virginia | March 23 | March 24 |

| Wisconsin | March 24 | March 25 |

| Wyoming | – | – |

|

NOTE: The Governor of Pennsylvania began ordering stay-at-home orders for some counties on March 23, before implementing a state-wide order effective April 1.

SOURCE: KFF analysis of state government websites.

|

||

Click here to download table (.xls)