Mental Illnesses May Soon Be the Most Common Pre-Existing Conditions

Cynthia Cox

Published:

The coronavirus pandemic has claimed over 200,000 American lives, left millions unemployed, and led to widespread social isolation. The pandemic has also understandably taken a toll on the nation’s mental health. In a recent KFF poll, more than half of adults in the United States reported that their mental health had been negatively impacted due to worry and stress over the coronavirus.

Meanwhile, a case brought before the Supreme Court by Republican-led states and supported by President Trump threatens to overturn the Affordable Care Act (ACA). If the ACA is overturned, mental illness could become one of the most common pre-existing conditions.

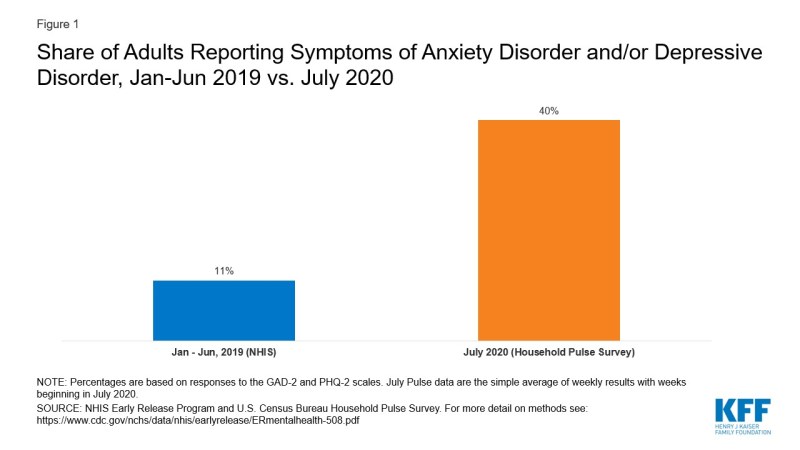

Before the pandemic began, in the first half of 2019, just over one in ten adults (11%) reported symptoms consistent with a diagnosable anxiety or depressive disorder. By July 2020, however, that number had skyrocketed to 40% (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Share of Adults Reporting Symptoms of Anxiety Disorder and/or Depressive Disorder, Jan-Jun 2019 vs. July 2020

With the sharp rise in people reporting symptoms of an anxiety and/or depressive disorder, mental illness now rivals obesity in prevalence among adults.

Before the ACA, the definition of a pre-existing condition in the individual insurance market was largely up to insurers to decide. There were some conditions that would almost always be declinable, meaning insurers wouldn’t offer coverage unless they were required to. Examples of declinable conditions include heart failure, recent cancers, and diabetes, to name a few.

Other conditions, like depression, might have led to a denial in some cases or an offer with higher premiums and/or exclusions in other cases. For example, according to a pre-ACA Humana underwriting manual, a person suffering from major depression that involved a hospitalization would be denied coverage, whereas a person with depression receiving counseling and no medication would be charged a 10-20% higher premium. For other insurers, recent use of some medications that treat mental illness, like Abilify, Lithium, and Clozapine, was another reason to deny individuals coverage before the ACA. If a person, perhaps because of stigma, failed to report a mental illness or medication during their application process, an insurer discovering this could later rescind the individual’s coverage.

Some people suffering from symptoms of anxiety or depression during the pandemic may not meet the criteria for a diagnosis, or have yet to receive a diagnosis or treatment. Regardless of whether a diagnosis was pre-existing, though, many individual market plans did not cover mental health care and substance abuse disorder services or medications for any enrollees, prior to the ACA’s requirement to cover Essential Health Benefits like mental health care.

Providers are encouraged to offer routine screening for depression for adults and adolescents, which could help many receive needed treatment, but may also leave them with a diagnosis on their medical record. With the ACA prohibiting insurers from discriminating against those with pre-existing conditions, people experiencing new symptoms of mental illness and other conditions no longer have to fear what an underwriter may discover in their medical records. That is, assuming the ACA’s broad protections for people with pre-existing conditions remain law.

Despite his administration arguing in court for pre-existing condition protections to be overturned with the rest of the ACA, President Trump has promised to still provide protections, but he has not released a replacement plan to do so. The Republican “Repeal and Replace” plans supported by President Trump in 2017 would have required insurers to enroll people with pre-existing conditions into their plan, but in an attempt to lower premiums, states were permitted to relax the ACA’s Essential Health Benefits, like mental health care. That could mean insurers offering coverage to people with mental illness, but not paying for their mental health care.

President Trump has also supported the expansion of so-called short-term plans (which can now be extended for up to three years). These plans offer a glimpse into what coverage would look like post-ACA if insurers are no longer required to offer the ACA’s Essential Health Benefits. In an analysis of these plans, we found that more than half of short-term plans didn’t offer coverage for mental illness at all, meaning even if a person with a mental illness was offered coverage, their plan wouldn’t pay for mental health treatment. Over a third of these plans would not pay for substance use treatment. Because short-term plans can deny coverage to people with pre-existing conditions, even insurers that do cover mental health care may not offer coverage to people with severe mental illness in the first place. In a post-ACA scenario where a hypothetical replacement plan prohibits insurers from denying coverage, but also does not require them to offer Essential Health Benefits, covered benefits could be even skimpier.

Protections for people with pre-existing conditions in the ACA go much further than prohibiting insurers from denying coverage. Not only do insurers have to offer coverage to people with common pre-existing conditions, like depression or anxiety, plans also have to cover treatment.