Both Remote and On-Site Workers are Grappling with Serious Mental Health Consequences of COVID-19

Rabah Kamal, Nirmita Panchal, and Rachel Garfield

Published:

While millions have recently lost their jobs or income and face new stresses, many who have been working during the pandemic also face new pressures. Almost overnight, the COVID-19 pandemic presented many workers with a whole host of concurrent risk factors for poor mental health and substance use problems, including generally high levels of uncertainty and fear, an overload of news and information, changes to workplace processes and demands, changes in household dynamics, financial and job security concerns, potential worsening of existing health conditions, and difficulties linked to caregiving. People working during the pandemic face unique threats to mental health and well being depending on which sector they work in and their potential exposure to the coronavirus. Generally speaking, surveys conducted during the pandemic have found that many workers have been experiencing burnout (which results from chronic workplace stress and can impact an individual’s motivation and productivity) and adverse mental health outcomes.

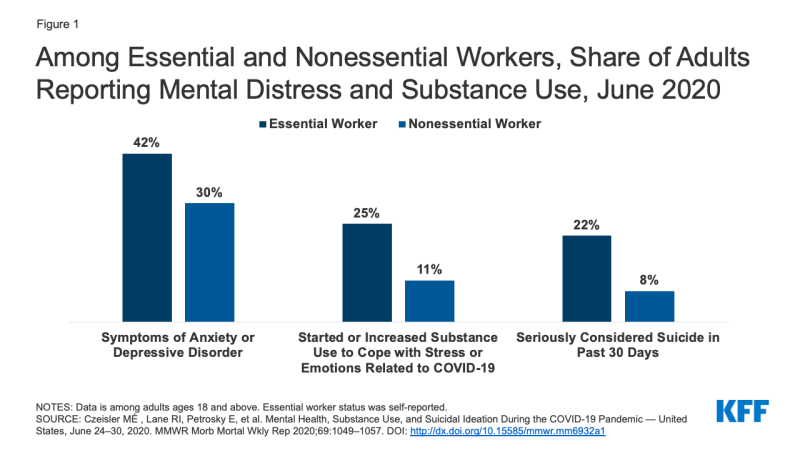

As the pandemic persists, frontline and other essential workers face particular risk of burnout and poor mental health outcomes. Roughly a third of U.S. adults report being essential workers during the pandemic, meaning they are still required to work outside their home during the pandemic, and they are more likely to be Black and low-income than non-essential workers who can work from home. Surveys conducted in June 2020 found that although a substantial share of all adult workers reported symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorder, essential workers reported these adverse effects more often than non-essential workers (42% vs 30%, as shown in Figure 1). Essential workers, compared to non-essential workers, also reported higher rates of substance use (25% vs 11%) and suicidal thoughts (22% vs 8%).

Figure 1: Among Essential and Nonessential Workers, Share of Adults Reporting Mental Distress and Substance Use, June 2020

Research has found that during pandemics, frontline health care providers are at higher risk of adverse psychological outcomes such as post-traumatic stress, insomnia, and suicidal ideation. During the COVID-19 pandemic, resource and staffing shortages and disrupted work-life balance have contributed to poor mental health outcomes for health care providers. Caregivers face unique risk of burnout and other adverse mental health outcomes as well, including those working in long-term care facilities and those who are unpaid and caring for family members or other loved ones needing support during the pandemic. Surveys from June 2020 found that 31% of unpaid caregivers for adults seriously considered suicide in the past 30 days.

High rates of burnout and adverse mental health impacts are reported among people working remotely during the pandemic. Many workers with the ability to work from home have been doing so during the pandemic. Combined with the closure of schools, daycares, and public spaces, this has left many workers not only newly working from home but also facing new stresses, additional responsibilities at home, and a fading work-life balance. Still many others who live alone shifted to working from home while also socially distancing in isolation, which is linked to poor mental health. Non–probability surveys conducted in summer 2020 found that many people working from home reported experiencing burnout, and nearly half of adults working from home experienced stress, anxiety, or depression. Many of these adults reported that these experiences began or worsened after they started working from home.

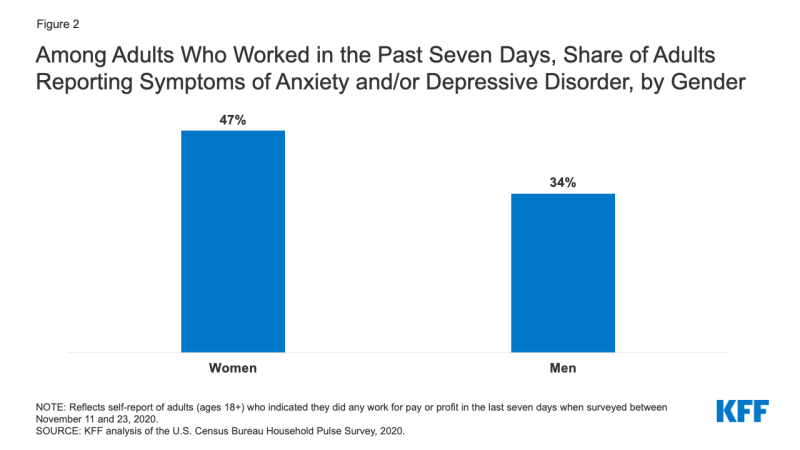

The pandemic has been disproportionately wearing on women in the workforce and has likely exacerbated existing gender disparities in career and financial opportunities and stability. Data from the Household Pulse Survey have consistently indicated that among adults who worked in the past seven days, a greater share of women than men reported symptoms of anxiety and/or depressive disorder (Figure 2). Other research shows that respondents who are women are more often experiencing adverse mental and physical health effects of the pandemic and that women in the workplace are more likely than men to report not feeling supported by leadership. Additionally, among parents who work full-time and have partners, mothers more often than fathers are likely to feel overwhelmed and unable to handle their workload. These disparate experiences could have significant long-term consequences for women in the workplace. A McKinsey and LeanIn.org analysis during the pandemic found that one in four women say they may either leave their job or cut down on their work, noting that working mothers, Black women, and women in leadership roles are uniquely at risk of leaving their jobs or cutting back on work.

Figure 2: Among Adults Who Worked in the Past Seven Days, Share of Adults Reporting Symptoms of Anxiety and/or Depressive Disorder, by Gender

Poor mental health among workers can have serious implications for both worker well being and economic outcomes. Importantly, the pandemic’s disparate impact on the mental health and well being of workers of color and working women highlights yet another vulnerability of groups already disproportionately impacted by the pandemic in numerous other ways. Both the human and fiscal impact of the pandemic’s toll on worker mental health will be important for employers and legislators to consider in determining the needs of the workforce through the remainder of the pandemic and beyond.

This work was supported in part by Well Being Trust. We value our funders. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.