Access and Coverage for Mental Health Care: Findings from the 2022 KFF Women’s Health Survey

Key Takeaways

- A significantly higher share of women (50%) than men (35%) thought they needed mental health services in the past two years. Among those who thought they needed mental health care, about six in ten women and men sought care in the past two years.

- Nearly two-thirds of young women ages 18-25 report needing mental health care in the past two years compared to one-third of women ages 50-64.

- Among all women ages 18-64 who thought they needed mental health services in the past two years, just half tried and were able to get an appointment for mental health care, 10% tried but were unable to get an appointment, and 40% did not seek care.

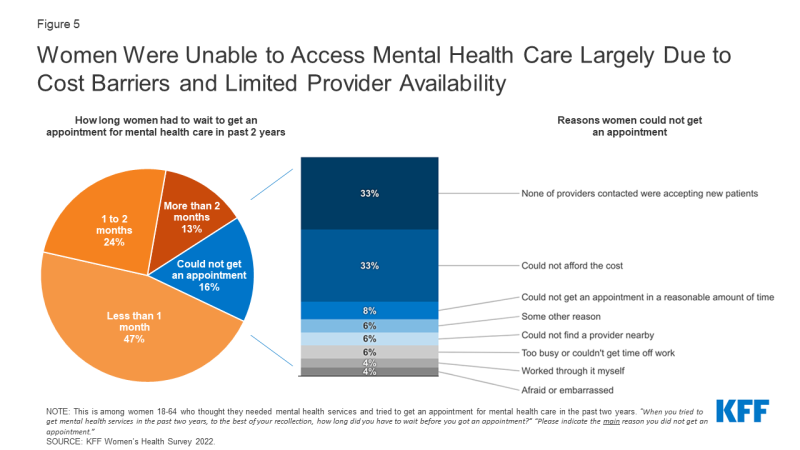

- Almost half of women who needed mental health services and tried to get care were able to get an appointment within a month, but more than one-third of women had to wait more than a month. Among those who could not get an appointment, women cite limited provider availability and cost as the main reasons they were unable to access mental health care.

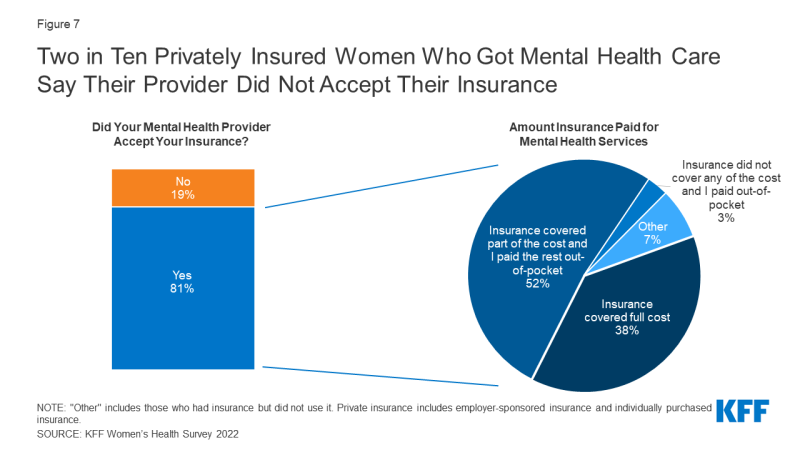

- Two in ten privately insured women with a mental health appointment in the past two years say their provider did not accept their insurance.

- Sixty percent of women had a telemedicine/telehealth visit in the past two years. Mental health care was the third most common reason women cited for accessing telehealth/telemedicine services, with 17% saying it was the primary purpose of their most recent telemedicine visit. The majority report that the quality of their telehealth visit was the same as an in-person visit.

Introduction

Mental health has emerged as a rapidly growing concern in recent years, with 90% of Americans saying there is a mental health crisis in a recent KFF-CNN poll. Women experience several mental health conditions more commonly than men, and some also experience mental health disorders that are unique to women, such as perinatal depression and premenstrual dysphoric disorders that may occur when hormone levels change. Data from the National Center for Health Statistics show that across all age groups, women were almost twice as likely to have depression and anxiety than men. The COVID-19 pandemic, the opioid epidemic, and racism are among commonly cited stressors that have exacerbated long-standing mental health issues and prompted growing demand for mental health services in the past two years, particularly among women.

This brief provides new data from the 2022 KFF Women’s Health Survey (WHS), a nationally representative survey of 5,145 women and 1,225 men ages 18-64 conducted primarily online from May 10, 2022, to June 7, 2022. In addition to several topics related to reproductive health and well-being, the survey asked respondents about their experiences accessing mental health services in the past two years. This issue brief presents KFF WHS data on mental health services access among self-identified women and men ages 18-64, and it also takes a closer look at mental health coverage among women. People of all genders, including non-binary people, were asked these questions; however, there are insufficient data to report on non-cisgendered people. See the Methodology section for details.

Utilization of Mental Health Services

Gender Differences

Half of women ages 18-64 (50%) thought they needed mental health services in the past two years (Figure 1) and a significantly smaller share of men report they needed mental health care (35%). Studies have long documented gender disparities in the rates and types of mental health conditions. Among those who thought they needed care, however, similar rates of women and men report seeking care. Sixty percent of women tried to make an appointment for mental health compared to 56% of men.

Need and Care Seeking

Nearly two thirds (64%) of women ages 18-25 thought they needed mental health services at some point in the past two years compared to just 35% of women ages 50-64 (Figure 2). Previous findings from the 2020 KFF WHS revealed that more than half of women (51%) said that worry or stress related to the coronavirus had affected their mental health. Other studies show that young adults, particularly women, experienced high incidence of depression and loneliness during the early stages of the pandemic.

More than half of women with low incomes (< 200% of the federal poverty level (FPL)) (55%) and women with Medicaid coverage (58%) thought they needed mental health care in the past two years compared to less than half (47%) of women with higher incomes (≥ 200% FPL) and those with private insurance (includes employer-sponsored insurance and individually purchased insurance) (47%). The FPL in 2022 for an individual is $13,590 (Figure 2).

Among those who thought they needed mental health care, larger shares of women ages 26-35 (63%) and women ages 36-49 (64%) sought care compared to 55% of women ages 50-64. Larger shares of women enrolled in Medicaid (67%) sought mental health services compared to women who have private insurance (58%) and women who are uninsured (50%) (Figure 3).

A significantly lower share of Asian/Pacific Islander women (40%) say they needed mental health services at some point in the past two years than their White counterparts (50%). Although not statistically significant, smaller shares of Asian/Pacific Islander women report seeking care compared to White women (50% vs. 62%). While the pandemic fueled violence against Asians and subsequently worsened anxiety and mental health for many, studies have shown that Asians reported greater cultural barriers to help-seeking such as family stigma and concerns about “losing face.” Cultural barriers may influence perceived need of care in addition to help-seeking behaviors.

Although the self-reported need for mental health care did not differ between Hispanic and White women (both 50%), smaller shares of Hispanic women (56%) sought care compared to White women (62%). Despite high rates of depression among Hispanic women, studies have shown that stigma and perceived discrimination in health care settings can contribute to underutilization of mental health services within Hispanic communities. Hispanic women also have the highest uninsured rate, which may limit their access to care.

Among the 50% of women who thought they needed mental health services, half (50%) were able to get an appointment, while another 40% did not try to get mental health services (Figure 4). One in ten (10%) who tried to get care were unable to make an appointment for mental health services. This suggests that the other half of women who report needing care may have unmet mental health needs.

Among all women who thought they needed mental health care and tried to get it in the past two years, nearly half (47%) had to wait less than a month for an appointment (Figure 5). One-quarter (24%) had to wait one to two months, and 13% had to wait more than two months to get care. The remaining 16% of those who sought mental health care could not get an appointment.

Among the 16% of women who needed care, sought care, and were unable to get an appointment for mental health services, the main reasons were limited provider availability and cost barriers. One-third of women who could not get an appointment say the main reasons were that they could not find a provider that was accepting new patients (33%) or that they could not afford the cost of mental health services (33%). Eight percent could not get an appointment in a reasonable amount of time and six percent say they could not find a provider nearby. Another 6% say they could not get an appointment for another reason, such as not wanting to go in-person due to COVID-19.

Our findings on provider availability are consistent with other studies on mental health access. A report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office found that many consumers with health insurance faced challenges finding in-network care. The country also faces a workforce shortage of behavioral health professionals in addition to other challenges with health care infrastructure that exacerbates issues with accessibility.

Figure 5: Women Were Unable to Access Mental Health Care Largely Due to Cost Barriers and Limited Provider Availability

Cost and Coverage for Mental Health Services

Among those who sought care but could not get an appointment, one-third (33%) say the main reason was that they could not afford it (Figure 5). Cost remains a barrier to mental health care access for some people with insurance and especially for those who lack coverage. Significantly larger shares of women who are uninsured (60%) say they could not get an appointment due to affordability reasons, compared to those who have health insurance either through private plans (33%) or Medicaid (30%) (Figure 6). There were no significant differences between women who have private insurance and women covered by Medicaid.

These findings on cost barriers are consistent with current literature, which has found that along with provider availability, affordability is one of the most prevalent barriers to mental health care.

While federal laws require special insurance protections such as parity for mental health care, gaps in coverage remain. All state Medicaid programs provide coverage for mental health services, and the Affordable Care Act (ACA) requires most private insurers to cover mental health care. However, the scope of coverage varies, provider networks are limited in many plans, and mental health providers may not accept all insurance plans. Some mental health practitioners do not accept insurance of any kind.

While most privately insured women who received mental health services in the past two years say their provider accepted their insurance for their most recent mental health visit (81%), two in ten (19%) say their provider did not. Among privately insured women who said their provider accepted their insurance, more than half report having out-of-pocket expenses for their most recent mental health visit. More than one-third (36%) say their insurance covered the full cost and 52% say their insurance covered some of the cost. Three percent say their insurance did not cover any of the cost. (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Two in Ten Privately Insured Women Who Got Mental Health Care Say Their Provider Did Not Accept Their Insurance

The Affordable Care Act requires that enrollees in most private health insurance plans have the right to appeal denied claims, though some evidence suggests that many are unfamiliar with appeals processes or are unaware of this protection. Among privately insured women whose insurance was not accepted by their mental health provider, 27% filed a claim with the health insurance plan to try to get reimbursed for some or all the cost (data not shown).

Telehealth

Social distancing during the pandemic contributed to a sharp increase in the provision of telehealth services, widening the access of counseling, therapy, prescribing, and other services via remote methods such as video and telephone. The rapid expansion of telemedicine/telehealth over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic has broadened access to health care for many, including access to mental health services. Mental health services provided via telehealth include speaking to a mental health provider over telephone or video, or through online apps such as Talkspace.

Sixty percent of women ages 18-64 had a telemedicine/telehealth visit in the past two years. Among these women, 17% say the primary purpose of their most recent visit was for mental health services (Figure 8). Accessing mental health care services was the third most common reason for telehealth visits, following annual check-ups (18%) and visits for minor illness or injury (18%). Three in ten women ages 18-25 (29%) say their most recent telehealth visit was for mental health services compared to 20% of women ages 26 to 35, 18% of women ages 36 to 49, and 10% of women ages 50 to 64 and older. A larger share of White women (21%) obtained mental health services at their most recent telehealth visit than Black women (13%), Hispanic women (14%), and Asian/Pacific Islander women (7%).

A larger share of women with Medicaid coverage (22%) report that their most recent telemedicine or telehealth visit was for mental health services than women who are privately insured (15%).

A similar share of women living in rural (23%) and urban/suburban (17%) areas report that the primary purpose of their most recent telehealth or telemedicine visit was for mental health services.

The majority (69%) of women who had a telehealth or telemedicine visit in the past two years for mental health care say the quality of care they received at their most recent visit was the same as an in-person visit for this type of care (Figure 9). One-in-five (19%) report receiving better quality of care during their telehealth visit, while 12% report experiencing worse quality than an in-person visit. These findings suggest the quality of mental health care is typically not diminished when accessing care via telehealth.

Conclusion

The demand for mental health care continues to surge as wait lists for professional help grow. Recent reports reveal that mental health providers across the nation are facing an overwhelming demand for services, leaving many individuals without care. Our survey finds that among the half of women who report that they thought they needed mental health services in the past two years, only half got an appointment for care. Unmet mental health needs are known to affect the overall well-being and productivity of individuals, families, and society, and studies have consistently shown that women are disproportionately affected by these unmet needs. Data from the 2022 KFF WHS underscore that addressing issues with provider availability and cost could improve access to mental health care for some. Our findings suggest that affordability barriers are a substantial obstacle for uninsured women.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic and other changes in the health policy environment, larger shares of employers began expanding coverage of mental health services by including more providers for in-person and telehealth care. Telehealth and telemedicine services have been recognized as an evolving strategy to increase access to care and address health needs, including care for mental health. We found that most women who received mental health services via telehealth say the quality of care they received was the same as in-person care. Telehealth has and likely will continue to play a role in addressing mental health access concerns for women.

Despite federal and state laws intended to expand and strengthen coverage for mental health care, gaps in coverage and problems with affordability continue to hinder access to mental health services even for those with private insurance and Medicaid. Our survey finds that in addition to challenges obtaining services, many women who have insurance faced at least some out-of-pocket costs for their visit. The findings from the 2022 KFF WHS suggest that future policies affecting telehealth, provider availability, health insurance coverage, and affordability will play a significant role in addressing the demand for mental health care.