Profile of Medicare Beneficiaries by Race and Ethnicity: A Chartpack

Published:

Issue Brief

Introduction

Medicare provides health insurance coverage for 55 million people ages 65 and over and younger adults with permanent disabilities. As the number of black and Hispanic beneficiaries has grown over time, the program has played an increasingly vital role as a source of coverage for people of color. Before the enactment of Medicare in 1965, health coverage and care was not easily accessible or affordable for many seniors, and perhaps least so for black seniors, who were often unable to receive treatment in the same facilities as whites because hospitals were segregated. The establishment of Medicare, in conjunction with the Civil Rights Act of 1964, was transformative in desegregating the nation’s health care system for patients and providers and in improving access to care.1,2,3

Medicare has helped to mitigate disparities in treatment and health outcomes across racial and ethnic groups, but gaps remain.4 For example, life expectancy at age 65 has improved over the past several decades, but nonetheless is lower for blacks than whites.5 Prior research has documented racial and ethnic disparities in the use of certain preventive services and diagnostic screenings, such as flu shots and prostate cancer screenings,6,7 in wait times for treatment, such as kidney transplants and cancer treatment,8,9 and in rates of hospital readmissions.10,11

Studies have also shown that among beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage plans, black and Hispanic enrollees are less likely than white enrollees to have their blood pressure, cholesterol, and glucose levels under control, though disparities in these clinical outcomes have lessened over time.12,13,14 Health disparities among Medicare beneficiaries of different racial and ethnic groups are related to a number of factors associated with broad social determinants of health, such as housing, income, and education,15,16 which affect health status and health outcomes long before the Medicare eligibility age is reached. Racial and ethnic disparities in care also have been attributed to variations in clinical treatment practices,17 differences in access to potentially higher-quality providers and facilities,18,19,20 and geographic variation.21 In addition, disparities in care among Hispanic beneficiaries have been attributed to cultural and language barriers.22,23,24

This chartpack draws on data and analysis from a variety of sources to profile the Medicare population through the lens of race and ethnicity, describing life expectancy, demographic characteristics, income and savings, health status and chronic conditions, supplemental coverage, selected measures of access to care, and service utilization (see “Data Sources” textbox below). In most cases, data are presented for the overall Medicare beneficiary population, and separately for white non-Hispanic, black non-Hispanic, and Hispanic Medicare beneficiaries. Sample size limitations generally preclude subgroup analysis of Asian, American Indian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander beneficiaries.

Key Findings

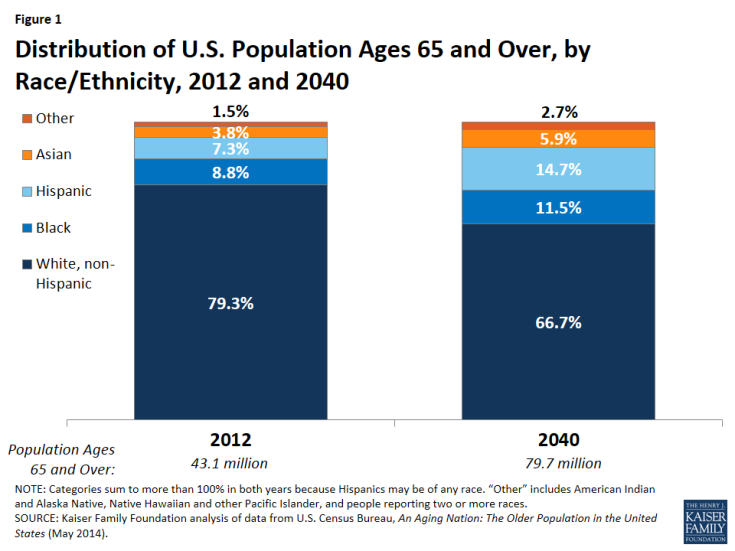

- People of color accounted for about one-fifth of adults ages 65 and over in 2012—including 9 percent black, 7 percent Hispanic, 4 percent Asian, and 1 percent other races—while non-white Hispanics were 79 percent of the 65 and over population. By 2040, people of color will comprise about one-third of the U.S. population ages 65 and over.

- The distribution of Medicare beneficiaries by race and ethnicity varies considerably in states across the country. In 7 states (Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, and South Carolina), at least 20 percent of all Medicare beneficiaries are black—at least twice the national average—while in Washington, D.C., 68 percent of beneficiaries are black. The 5 states with the highest share of Hispanic beneficiaries are California, Florida, New Mexico, New York, and Texas.

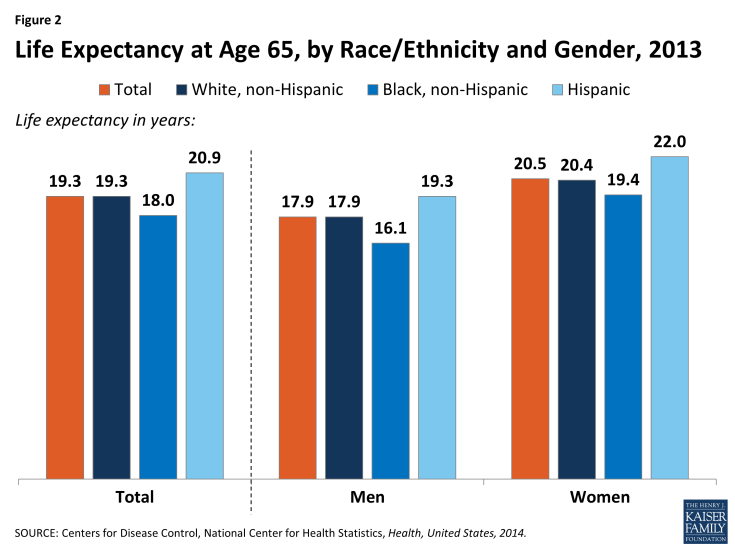

- Life expectancy at age 65 has improved over the past several decades, but continues to vary by race and ethnicity. Life expectancy at 65 is lower for blacks than whites (18 years versus 19 years), but higher for Hispanics at age 65 (21 years) than for whites and blacks.

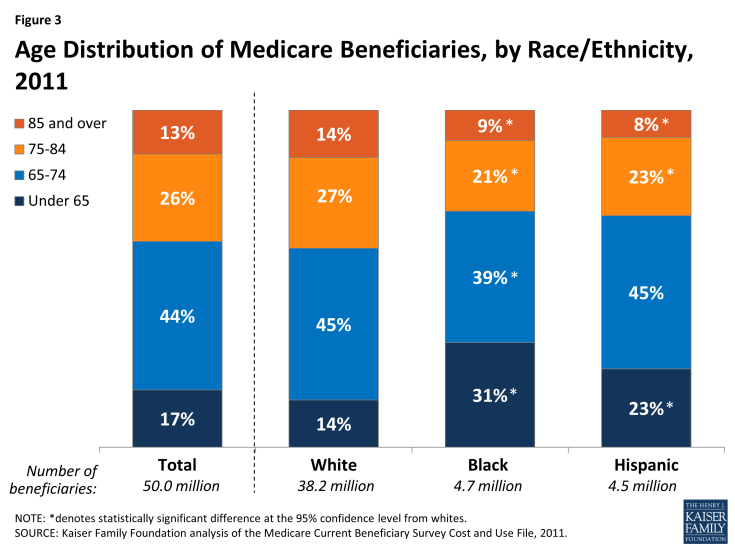

- Compared to white beneficiaries, black and Hispanic Medicare beneficiaries are more likely to be under the age of 65, have more limited financial resources, and report poorer health status.

- The majority (83%) of Medicare beneficiaries are ages 65 and older, while 17 percent are under age 65 and qualify for Medicare because of a permanent disability. However, a much larger share of black (31%) and Hispanic beneficiaries (23%) than white beneficiaries (14%) are under age 65 and living with disabilities.

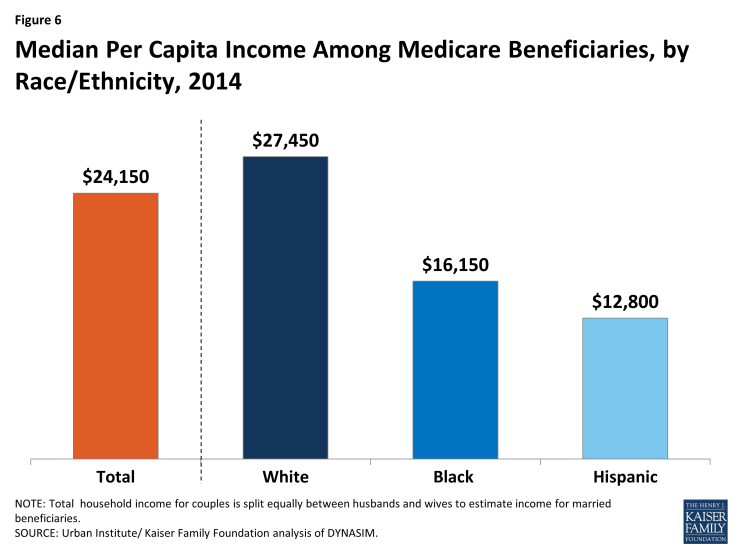

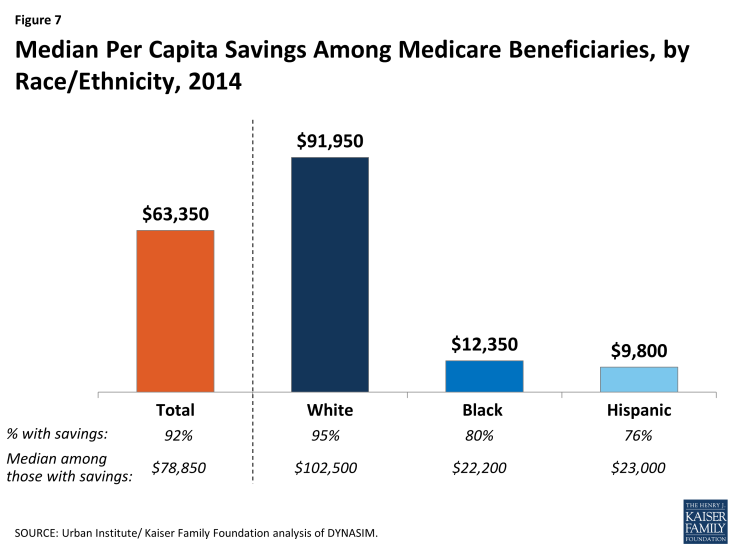

- Median per person income in 2014 for black and Hispanic Medicare beneficiaries ($16,150 and $12,800, respectively) was considerably lower than for white Medicare beneficiaries ($27,450). In 2014, half of all Medicare beneficiaries had less than $63,350 in savings, but the amount of savings was seven times greater for white beneficiaries ($91,950) than black ($12,350) or Hispanic ($9,800) beneficiaries.

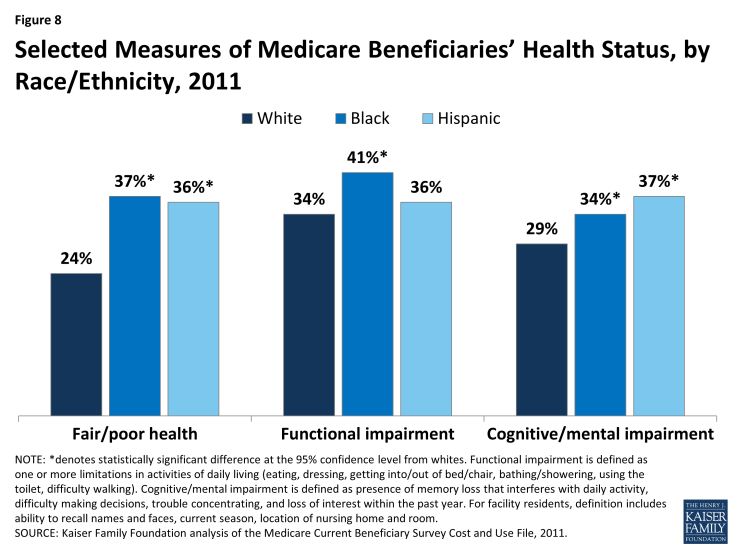

- A larger share of black (37%) and Hispanic (36%) Medicare beneficiaries than white beneficiaries (24%) report fair or poor health status.

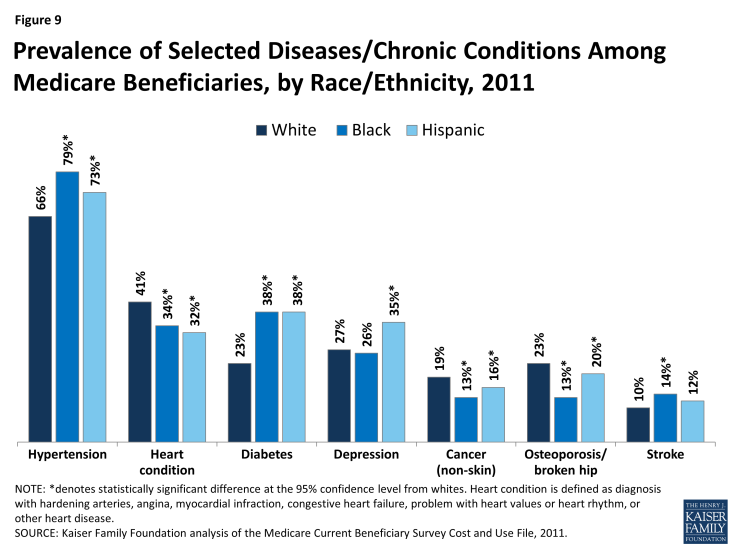

- The prevalence of chronic conditions among Medicare beneficiaries varies widely by racial and ethnic groups. For example, a larger share of black (79%) and Hispanic (73%) beneficiaries have hypertension than white beneficiaries (66%), while heart conditions are more common among white beneficiaries.

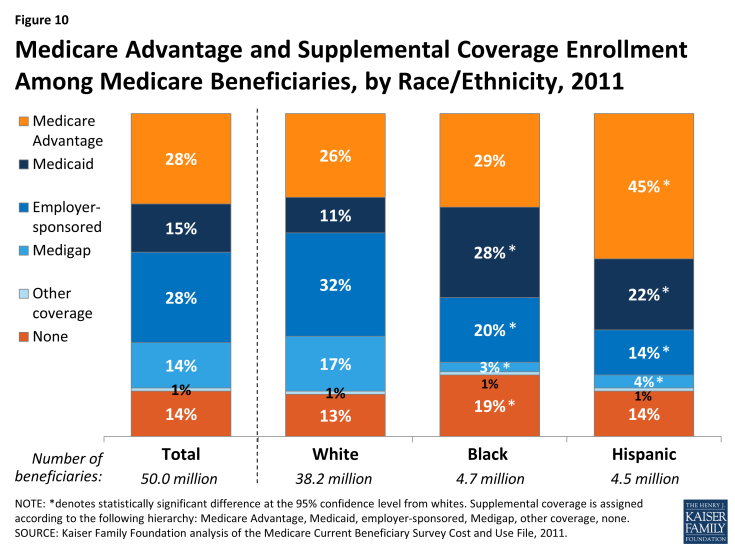

- Close to half (45%) of all Hispanic beneficiaries were enrolled in Medicare Advantage in 2011, a far higher share than among black (29%) or white (26%) beneficiaries.

- Sources of supplemental insurance coverage vary by race and ethnicity, with a significantly smaller share of black (20%) and Hispanic (14%) beneficiaries having coverage from an employer-sponsored plan compared to white beneficiaries (32%) in 2011. Additionally, a larger share of black (28%) and Hispanic (22%) beneficiaries than white beneficiaries (11%) rely on Medicaid to supplement Medicare, based primarily on lower incomes among blacks and Hispanics. Nearly one in five (19%) black beneficiaries had no source of supplemental insurance in 2011, a larger share than among white beneficiaries (13%).

- Measures of access to care and utilization of services vary by race/ethnicity:

- Overall, Medicare beneficiaries have broad access to physicians, hospitals, and other health care providers, and only a small share overall report problems with access to care. While only a small share of beneficiaries overall report access to care problems, a slightly larger share of black and Hispanic beneficiaries report trouble getting needed care (7% and 9%, respectively) than white beneficiaries (5%).

- A larger share of black beneficiaries than white beneficiaries had at least one emergency department visit during the year in 2011 (37% versus 28%). This variation is likely related to a larger share of black beneficiaries reporting fair or poor health status; nonetheless, even among beneficiaries self-reporting good health, a larger share of black beneficiaries than white beneficiaries had at least one visit to the emergency department during the year (30% versus 22%).

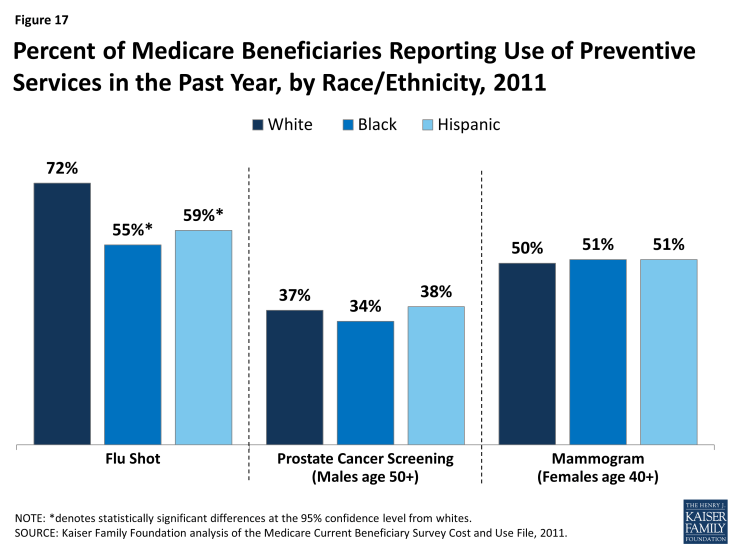

- In terms of preventive services, the share of beneficiaries receiving an influenza vaccination in 2011 was higher among white beneficiaries (72%) than among black (55%) and Hispanic beneficiaries (59%); there were no notable differences by race and ethnicity in receipt of other preventive services, such as mammograms and prostate cancer screenings, in 2011.

Discussion

It has now been three decades since Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Margaret Heckler issued a landmark report documenting “the sad and significant fact” of ongoing disparities in the burden of illness between non-Hispanic whites and people of color.25 Since then, a number of efforts have been launched to measure and minimize these gaps.26,27 Most recently, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has proposed a set of initiatives to reduce disparities in hospital readmissions rates and improve quality of care for racially and ethnically diverse beneficiaries.28,29,30,31 Such efforts may help to address observed health disparities among Medicare beneficiaries of different racial and ethnic groups. Ultimately, achieving health equity for all Medicare beneficiaries will involve not only improving coverage for adults prior to age 65, but also addressing the specific cultural, linguistic, and socioeconomic needs of racially and ethnically diverse groups at all ages.

| Data Sources Used in This Analysis |

|

This chartpack was prepared by Christa Fields, Juliette Cubanski, Cristina Boccuti, and Tricia Neuman of the Kaiser Family Foundation. Data programming and statistical analysis was conducted by Anthony Damico, an independent consultant.

Chartpack

Distribution of U.S. Population Ages 65 and Over by Race/Ethnicity, 2012 and 2040

In 2012, 79.3 percent of U.S. adults ages 65 and over were white non-Hispanic, 8.8 percent were black, 7.3 percent were Hispanic, 3.8 percent were Asian, and 1.5 percent were other races (Figure 1).1 The racial and ethnic profile of people ages 65 and over is expected to shift over time. By 2040, non-Hispanic whites are projected to comprise a smaller share (66.7%) of the population ages 65 and over, while the share of Hispanics is projected to double to 14.7 percent. The share of the U.S. population ages 65 and over who are black and Asian is also projected to increase.

The distribution of all Medicare beneficiaries, including seniors and people under age 65, by race and ethnicity varies considerably across the country (Table 1). In 7 states (Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, and South Carolina), at least 20 percent of all Medicare beneficiaries are black—at least twice the national average—while in Washington, D.C., 68 percent of beneficiaries are black. The 5 states with the highest share of Hispanic beneficiaries are California, Florida, New Mexico, New York, and Texas.

Life Expectancy at Age 65, by Race/Ethnicity and Gender, 2013

Adults in the U.S. who lived to age 65 in 2013 could expect to live another 19.3 years, on average (Figure 2). This reflects a five-year improvement in life expectancy since 1960, prior to the enactment of Medicare. Life expectancy at age 65 varies by race and ethnicity, and is lower for blacks at age 65 than for whites (18.0 years versus 19.3 years) and highest for Hispanic adults (20.9 years). This is the case despite the relatively low socioeconomic status of the Hispanic population, and has been attributed to low rates of smoking and other healthy behaviors among first-generation Hispanics.2,3 This life expectancy advantage among Hispanics is not expected to continue into the future, however, due to higher rates of smoking and obesity among second- and third- generation Hispanic adults.4 Among people in all three groups, life expectancy at age 65 is higher for women than men.

Age Distribution of Medicare Beneficiaries, by Race/Ethnicity, 2011

The majority (83%) of Medicare beneficiaries are ages 65 and older, and another 17 percent are younger than age 65 and qualify for Medicare because of a long-term disability (Figure 3, Table 2). A much larger share of black (31%) and Hispanic beneficiaries (23%) than white beneficiaries (14%) are under age 65 and living with a permanent disability. Conversely, a smaller share of black (9%) and Hispanic beneficiaries (8%) than white beneficiaries (14%) are ages 85 and over.

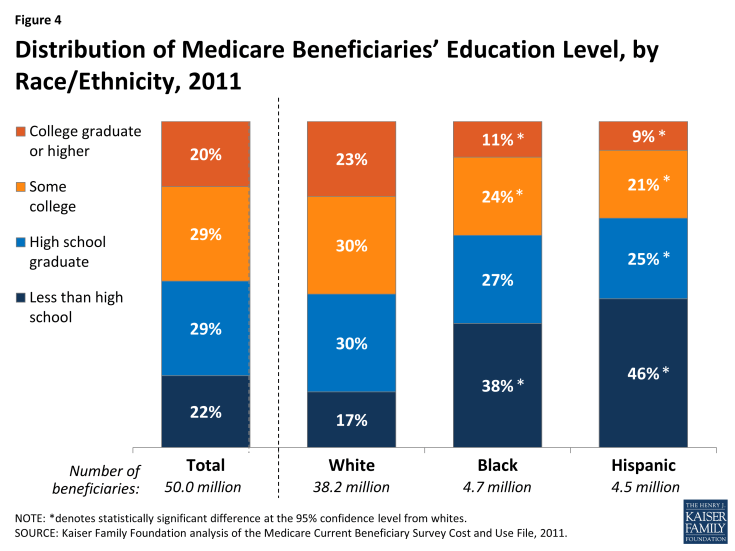

Distribution of Medicare Beneficiaries’ Education Level, by Race/Ethnicity, 2011

The education level of Medicare beneficiaries varies by race and ethnicity, with a significantly larger share of black and Hispanic beneficiaries than white beneficiaries having less than a high school education (38%, 46%, and 17%, respectively) (Figure 4, Table 2). Smaller shares of black and Hispanic beneficiaries than white beneficiaries have some college education (24%, 21%, and 30%, respectively) or a college degree (11%, 9%, and 23%, respectively).

Official and Supplemental Poverty Rates Among Adults Ages 65 and Over, by Race/Ethnicity, 2014

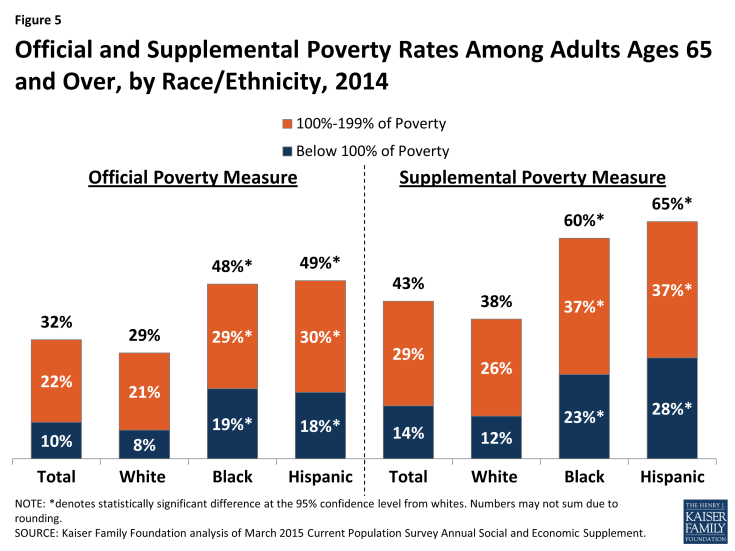

The rate of poverty is much higher among black and Hispanic adults ages 65 and over than among white older adults, whether measured by the official poverty measure or the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM) (Figure 5). The SPM differs from the official poverty measure in a number of ways, and takes into account available financial resources including liabilities (e.g., taxes), the value of in-kind benefits (e.g., food stamps), out-of-pocket medical spending (which is generally higher among older adults), geographic variation in housing expenses, and other factors.5 Under the official poverty measure, about one in five black (19%) and Hispanic (18%) seniors were living in poverty in 2014, compared to just 8 percent of white adults ages 65 and over. Rates of poverty for all three groups were higher under the SPM in 2014, with 28 percent of Hispanic seniors, 23 percent of black seniors, and 12 percent of white seniors living below the SPM poverty thresholds that year. A significantly larger share of Hispanic (65%) and black (60%) seniors than white seniors (38%) lived below 200 percent of poverty under the SPM.

Figure 5: Official and Supplemental Poverty Rates Among Adults Ages 65 and Over, by Race/Ethnicity, 2014

Median Per Capita Income Among Medicare Beneficiaries, by Race/Ethnicity, 2014

In 2014, half of all Medicare beneficiaries had incomes below $24,150 (Figure 6). Median per capita income was substantially lower for black and Hispanic Medicare beneficiaries ($16,150 and $12,800, respectively) than for white beneficiaries ($27,450).6

Median Per Capita Savings Among Medicare Beneficiaries, by Race/Ethnicity, 2014

In 2014, half of all Medicare beneficiaries had less than $63,350 in savings, but the amount of median per capita savings was seven times greater for white beneficiaries ($91,950) than black or Hispanic beneficiaries ($12,350 and $9,800, respectively) (Figure 7).7 Nearly all Medicare beneficiaries had some amount of savings (92%), but savings rates were higher among white beneficiaries (95%) than among black and Hispanic beneficiaries (80% and 76%, respectively). Among those with any savings, the median savings amount was roughly five times higher for white beneficiaries ($102,500) than for black and Hispanic beneficiaries ($22,200 and $23,000, respectively).

Selected Measures of Medicare Beneficiaries’ Health Status, by Race/Ethnicity, 2011

Measures of Medicare beneficiaries’ health status differ for beneficiaries of different racial and ethnic groups (Figure 8; Table 3). For example, more than one third of all black and Hispanic Medicare beneficiaries (37% and 36%, respectively) report being in fair or poor health, compared to roughly one fourth (24%) of white beneficiaries. About four in 10 black beneficiaries (41%) lives with a functional impairment, defined as having one or more limitations in activities of daily living (ADLs) such as eating or bathing, a larger share than Hispanic and white beneficiaries with functional impairments (36% and 34%, respectively). A larger share of Hispanic (37%) and black (34%) beneficiaries than white beneficiaries (29%) has a cognitive or mental impairment. Poorer health status among black and Hispanic beneficiaries may reflect the disproportionate share of beneficiaries under age 65 with permanent disabilities in these groups, as shown earlier (see Figure 3).

Prevalence of Selected Diseases/Chronic Conditions Among Medicare Beneficiaries, by Race/Ethnicity, 2011

The prevalence of chronic conditions among Medicare beneficiaries varies widely by racial and ethnic groups and by age (Figure 9; Table 3). Hypertension is common among all Medicare beneficiaries, but a larger share of black (79%) and Hispanic (73%) beneficiaries have hypertension than white beneficiaries (66%). Conversely, heart conditions, such as hardening of the arteries, angina, myocardial infarction, and congestive heart failure, are more common among white beneficiaries (41%) than among black or Hispanic beneficiaries (34% and 32%, respectively). A significantly larger share of black and Hispanic beneficiaries than white beneficiaries have diabetes (38%, 38%, and 23%, respectively), while the prevalence of depression is highest among Hispanic beneficiaries (35%) than among white or black beneficiaries. Cancer, osteoporosis, and stroke also show varying prevalence rates across different racial and ethnic groups, with rates of cancer and osteoporosis highest for white beneficiaries, and strokes affecting a larger share of black than white beneficiaries. Additionally, research has shown that the prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease increases with age, and among beneficiaries ages 85 and over, is highest among Hispanic (44%) and black (29%) beneficiaries than among white beneficiaries (22%).8

Figure 9: Prevalence of Selected Diseases/Chronic Conditions Among Medicare Beneficiaries, by Race/Ethnicity, 2011

Medicare Advantage and Sources of Supplemental Coverage Among Medicare Beneficiaries, by Race/Ethnicity, 2011

In 2011, about three in 10 (28%) Medicare beneficiaries overall were enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan, such as an HMO or PPO, but enrollment rates were significantly higher among Hispanic beneficiaries (45%) than among black (29%) or white (26%) beneficiaries (Figure 10).

Most Medicare beneficiaries had some form of supplemental insurance coverage to help cover Medicare’s cost-sharing requirements and fill in gaps in Medicare’s benefit package, but sources of coverage varied across racial and ethnic groups. Medicaid plays a key role in supplementing Medicare for low-income Medicare beneficiaries, covering a much larger share of black (28%) and Hispanic (22%) beneficiaries than white (11%) beneficiaries. In contrast, employer-sponsored coverage is the primary source of supplemental coverage for white beneficiaries (32%) and another 17 percent have Medigap policies; both supplemental insurance types cover smaller shares of black and Hispanic beneficiaries. While a relatively small share (14%) of beneficiaries overall lacked any source of supplemental coverage in 2011, nearly one in five (19%) black beneficiaries had no form of supplemental coverage in 2011, potentially exposing them to higher out-of-pocket costs.

Figure 10: Prevalence of Selected Diseases/Chronic Conditions Among Medicare Beneficiaries, by Race/Ethnicity, 2011

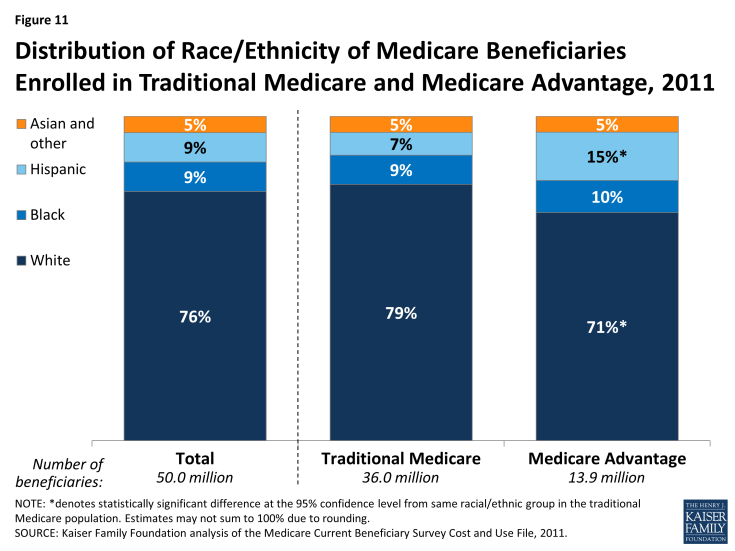

Distribution of Race/Ethnicity of Medicare Beneficiaries Enrolled in Traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage, 2011

Hispanic beneficiaries comprised 9 percent of the total Medicare population in 2011, but a disproportionate share (15%) of enrollees in Medicare Advantage plans (Figure 11). Relatively high Medicare Advantage enrollment among Hispanic beneficiaries is in part attributable to geography, with larger shares of Hispanic beneficiaries living in states with relatively high Medicare Advantage penetration (e.g., Florida and California).9 Black beneficiaries comprise about one in 10 Medicare beneficiaries in both traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage. A smaller share of white beneficiaries are enrolled in Medicare Advantage (71%) than in traditional Medicare (79%).

Figure 11: Distribution of Race/Ethnicity of Medicare Beneficiaries Enrolled in Traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage, 2011

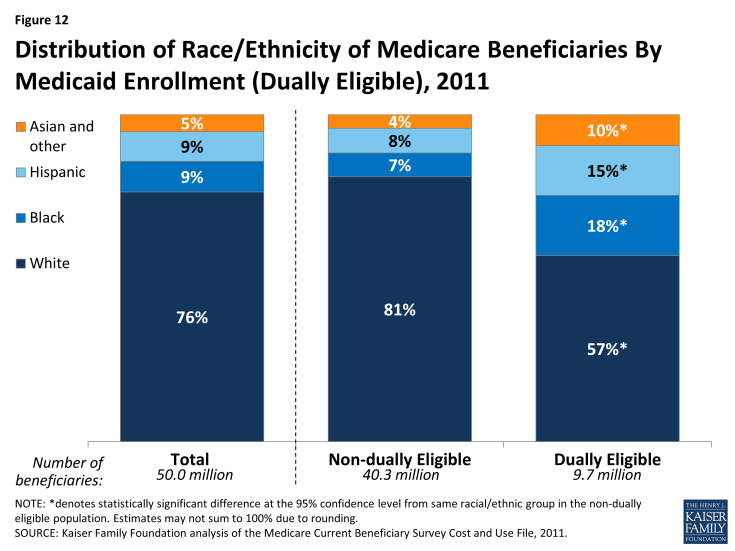

Distribution of Race/Ethnicity of Medicare Beneficiaries By Medicaid Enrollment (Dually Eligible), 2011

Nearly 10 million Medicare beneficiaries with low incomes and modest savings receive additional assistance from the Medicaid program, which includes premium assistance and may include cost-sharing assistance for Medicare-covered services along with extra benefits Medicare does not cover, such as dental and long-term services and supports (Figure 12). The dually eligible beneficiary population has a very different racial and ethnic composition than the non-dually eligible population. Black and Hispanic beneficiaries comprise 15 percent of non-dually eligible beneficiaries, but one third (33%) of beneficiaries who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, consistent with these groups having generally lower incomes and fewer resources than white beneficiaries.

Figure 12: Distribution of Race/Ethnicity of Medicare Beneficiaries By Medicaid Enrollment (Dually Eligible), 2011

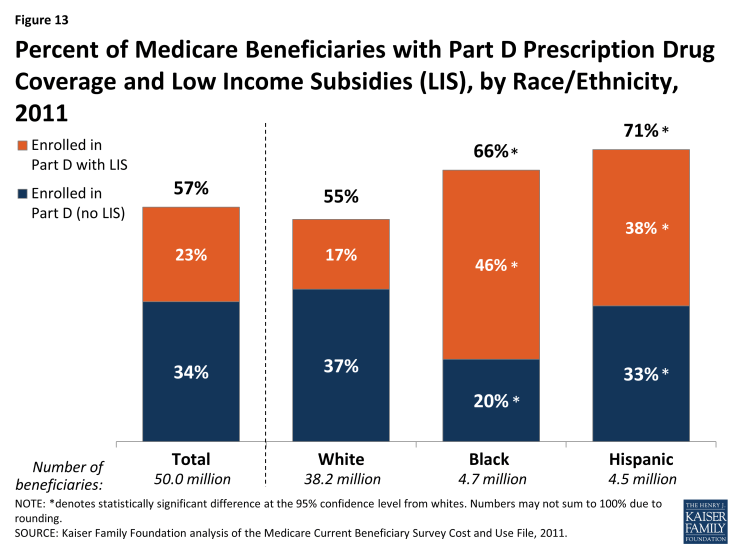

Percent of Medicare Beneficiaries with Part D Prescription Drug Coverage and Low Income Subsidies (LIS), 2011

The Medicare Part D prescription drug benefit is an important source of drug coverage for Medicare beneficiaries. More than half of all Medicare beneficiaries (57%) were enrolled in a Part D drug plan in 2011, but a larger share of black (66%) and Hispanic (71%) beneficiaries than white beneficiaries (55%) had Part D drug coverage (Figure 13). A smaller share of white beneficiaries may be enrolled in Part D than other beneficiaries because they are more likely to have drug coverage through an employer-sponsored plan (see Figure 10). Medicare beneficiaries with low income and modest assets may qualify for additional financial premium and cost-sharing assistance through the Part D low-income subsidy (LIS) program. Nearly half of all black beneficiaries (46%) and more than one third of all Hispanic beneficiaries (38%) receive LIS under Part D, larger than the share of white beneficiaries with LIS (17%), due to lower levels of income and assets among black and Hispanic beneficiaries.

Figure 13: Percent of Medicare Beneficiaries with Part D Prescription Drug Coverage and Low Income Subsidies (LIS), by Race/Ethnicity, 2011

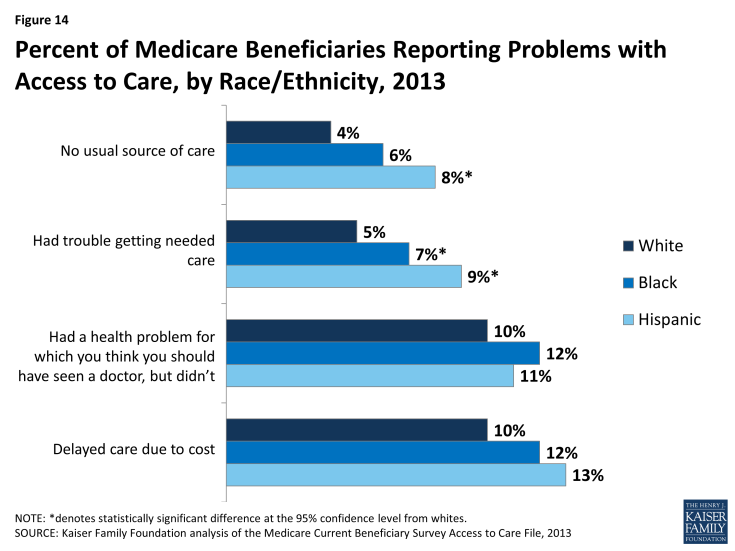

Percent of Medicare Beneficiaries Reporting Problems with Access to Care, by Race/Ethnicity, 2013

Overall, Medicare beneficiaries have broad access to physicians, hospitals, and other health care providers, and report generally low rates of problems across a number of access measures. Some variation is seen, however, by race and ethnicity (Figure 14; Table 4). A slightly larger share of Hispanic (8%) than white beneficiaries (4%) report not having a usual source of care to go to when they are sick or seeking medical advice, while a somewhat larger share of black and Hispanic beneficiaries (7% and 9%, respectively) report trouble getting needed care than whites (5%).

Figure 14: Percent of Medicare Beneficiaries Reporting Problems with Access to Care, by Race/Ethnicity, 2013

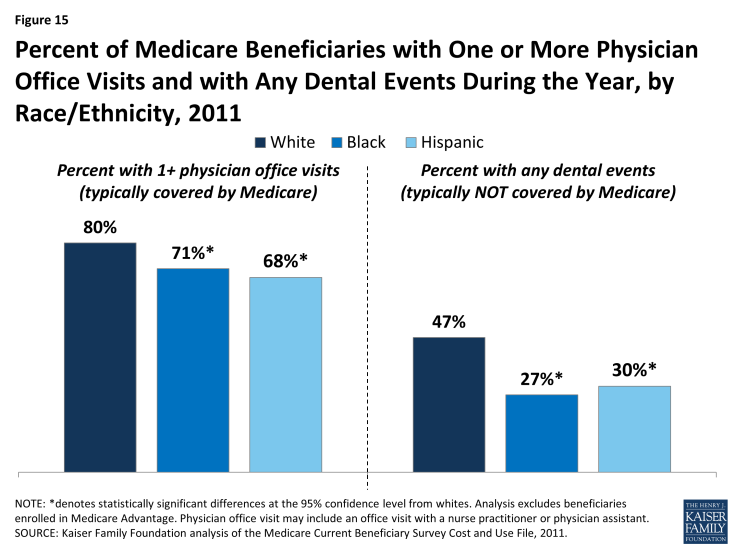

Percent of Medicare Beneficiaries with One or More Physician Office Visits and with Any Dental Events During the Year, by Race/Ethnicity, 2011

The majority of all beneficiaries in traditional Medicare saw a physician in 2011, with a somewhat larger share of white beneficiaries (80%) having a physician office visit than black or Hispanic beneficiaries (71% and 68%, respectively) (Figure 15; Table 5). In contrast, less than half of all beneficiaries in traditional Medicare had any dental events during the year, but larger differences by race and ethnicity are observed for using dental services. Nearly half of white beneficiaries (47%) had a dental event during the year, a significantly larger share than among black (27%) and Hispanic (30%) beneficiaries.10 The smaller share of beneficiaries seeing a dentist during the year than a physician is likely due to the lack of coverage under traditional Medicare for routine dental care (including checkups, fillings, dentures, and root canals) and the out-of-pocket costs associated with dental care.11

Figure 15: Percent of Medicare Beneficiaries with One or More Physician Office Visits and with Any Dental Events During the Year, by Race/Ethnicity, 2011

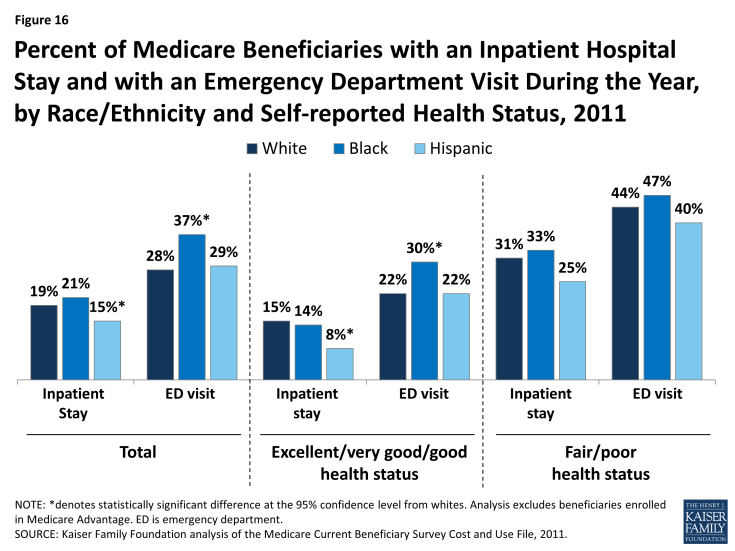

Percent of Medicare Beneficiaries with an Inpatient Hospital Stay and with an Emergency Department Visit During the Year, by Race/Ethnicity and Self-reported Health Status, 2011

Among beneficiaries enrolled in traditional Medicare, some differences by race and ethnicity are observed in the share of beneficiaries with one or more inpatient hospital stays and emergency department visits in the year (Figure 16; Table 5). For instance, a smaller share of Hispanic beneficiaries had an inpatient hospital stay in 2011 than white beneficiaries (15% versus 19%), and a larger share of black beneficiaries had one or more emergency department visits in the year compared with whites (37% versus 28%). This variation is likely related to overall differences in health status by race and ethnicity, as discussed earlier. That is, as health status worsens, higher rates of hospitalizations are to be expected. In fact, no statistically significant differences between whites and people of color are seen in the share of beneficiaries reporting fair or poor health who had at least one inpatient hospitalization or emergency department visit. In contrast, among beneficiaries in relatively better health (defined as excellent, very good, or good self-reported health status), a larger share of black beneficiaries (30%) had an emergency department visit compared to white beneficiaries (22%); and a smaller share of Hispanic beneficiaries had an inpatient hospital stay (8%) than white beneficiaries (15%).

Additionally, a larger share of black beneficiaries than white beneficiaries had two or more hospital stays during the year in 2011 (10% versus 6%) (Table 5)—a difference also observed among beneficiaries in fair or poor health (18% of black beneficiaries versus 13% of white beneficiaries). Hospital readmissions, which have been found to be higher among black beneficiaries, may be a factor in these results.12,13

Figure 16: Percent of Medicare Beneficiaries with an Inpatient Hospital Stay and with an Emergency Department Visit During the Year, by Race/Ethnicity and Self-reported Health Status, 2011

Percent of Medicare Beneficiaries Reporting Use of Preventive Services in the Past Year, by Race/Ethnicity, 2011

Medicare covers routine preventive services, such as annual wellness exams and immunizations. In 2011, the share of beneficiaries receiving an influenza vaccination in the past year was higher among white beneficiaries (72%) than among black (55%) and Hispanic beneficiaries (59%) (Figure 17). Overall, more than one-third (37%) of male beneficiaries ages 50 and older reported receiving a prostate cancer screening in 2011, with no statistically significant differences by race or ethnicity. And half (50%) of all female beneficiaries ages 40 and older reported receiving a mammogram in the past year, with no significant differences by race or ethnicity. Previous research has identified racial and ethnic disparities in receipt of mammograms, but more recent research suggests that this gap has narrowed, consistent with the findings presented here.14

Figure 17: Percent of Medicare Beneficiaries Reporting Use of Preventive Services in the Past Year, by Race/Ethnicity, 2011

Tables

| Table 1: Percent of State Medicare Beneficiary Populations, by Race/Ethnicity, 2014 | |||||

| State | Number of Beneficiaries | Percent White | Percent Black | Percent Hispanic | Percent Other Race/Ethnicity |

| United States Total | 50,546,000 | 76% | 10% | 8% | 5% |

| Alabama | 850,000 | 77% | 21% | N/A | N/A |

| Alaska | 71,000 | 71% | N/A | N/A | 24% |

| Arizona | 1,031,000 | 71% | 4% | N/A | N/A |

| Arkansas | 560,000 | 82% | 14% | N/A | N/A |

| California | 5,272,000 | 57% | 6% | 20% | 16% |

| Colorado | 772,000 | 85% | 4% | 8% | 3% |

| Connecticut | 521,000 | 82% | 8% | 7% | N/A |

| Delaware | 173,000 | 79% | 16% | N/A | N/A |

| District of Columbia | 77,000 | 25% | 68% | 5% | N/A |

| Florida | 3,804,000 | 71% | 9% | 17% | 2% |

| Georgia | 1,431,000 | 72% | 24% | N/A | 2% |

| Hawaii | 231,000 | 25% | N/A | 4% | 70% |

| Idaho | 212,000 | 93% | N/A | 4% | N/A |

| Illinois | 1,981,000 | 75% | 13% | 6% | 5% |

| Indiana | 1,135,000 | 92% | 6% | N/A | N/A |

| Iowa | 518,000 | 97% | 2% | N/A | N/A |

| Kansas | 444,000 | 86% | 4% | N/A | 6% |

| Kentucky | 843,000 | 94% | 5% | N/A | N/A |

| Louisiana | 635,000 | 68% | 26% | N/A | N/A |

| Maine | 273,000 | 96% | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Maryland | 865,000 | 64% | 25% | N/A | 7% |

| Massachusetts | 1,105,000 | 82% | 6% | 7% | 6% |

| Michigan | 1,743,000 | 84% | 12% | 2% | 2% |

| Minnesota | 848,000 | 92% | 1% | N/A | 5% |

| Mississippi | 495,000 | 66% | 31% | N/A | N/A |

| Missouri | 1,050,000 | 87% | 8% | N/A | 3% |

| Montana | 182,000 | 97% | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Nebraska | 306,000 | 95% | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Nevada | 423,000 | 69% | 7% | 10% | 13% |

| New Hampshire | 226,000 | 96% | N/A | N/A | 3% |

| New Jersey | 1,417,000 | 73% | 12% | 9% | 6% |

| New Mexico | 355,000 | 64% | N/A | 28% | N/A |

| New York | 3,148,000 | 71% | 11% | 11% | 8% |

| North Carolina | 1,641,000 | 74% | 20% | 2% | N/A |

| North Dakota | 105,000 | 95% | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Ohio | 2,181,000 | 86% | 11% | N/A | N/A |

| Oklahoma | 600,000 | 83% | 7% | N/A | 8% |

| Oregon | 764,000 | 90% | N/A | 3% | 6% |

| Pennsylvania | 2,375,000 | 85% | 9% | 3% | 2% |

| Rhode Island | 174,000 | 88% | 3% | 5% | N/A |

| South Carolina | 834,000 | 76% | 22% | N/A | N/A |

| South Dakota | 143,000 | 94% | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Tennessee | 1,141,000 | 85% | 13% | N/A | N/A |

| Texas | 3,384,000 | 63% | 11% | 22% | 4% |

| Utah | 337,000 | 93% | N/A | 4% | N/A |

| Vermont | 112,000 | 98% | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Virginia | 1,212,000 | 74% | 17% | 3% | 5% |

| Washington | 1,112,000 | 84% | 3% | 4% | 9% |

| West Virginia | 389,000 | 95% | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Wisconsin | 967,000 | 91% | 4% | 2% | N/A |

| Wyoming | 76,000 | 94% | N/A | 4% | N/A |

| NOTE: Persons of Hispanic origin may be of any race; all other racial/ethnic groups are non-Hispanic. “Other” category includes Asians, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders, American Indians, Aleutians, Eskimos and persons identifying two or more races. These groups have been combined due to their small populations in many states which prevent meaningful statistical analyses of the groups individually. N/A: estimates with relative standard errors greater than 30% are not provided and often correspond to low sample size.

SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the March 2015 Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement. |

|||||

| Table 2: Characteristics of Medicare Beneficiaries, by Race/Ethnicity, 2011 | ||||

| Measure | Total | White | Black | Hispanic |

| Number of beneficiaries1 | 50.0 million | 38.2 million | 4.7 million | 4.5 million |

| Share of beneficiaries | 100% | 76% | 9% | 9% |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 45% | 45% | 43% | 49% |

| Female | 55% | 55% | 57% | 51% |

| Age in years | ||||

| Under 65 | 17% | 14% | 31%* | 23%* |

| 65-74 | 44% | 45% | 39%* | 45% |

| 75-84 | 26% | 27% | 21%* | 23%* |

| 85+ | 13% | 14% | 9%* | 8%* |

| Education level | ||||

| Less than high school | 22% | 17% | 38%* | 46%* |

| High school graduate | 29% | 30% | 27% | 25%* |

| Some college or 2-year degree | 29% | 30% | 24%* | 21%* |

| College graduate or more | 20% | 23% | 11%* | 9%* |

| Metropolitan status | ||||

| Metro | 77% | 74% | 85%* | 92%* |

| Non-metro | 23% | 26% | 15%* | 8%* |

| Type of residence | ||||

| Community | 95% | 95% | 96% | 97%* |

| Facility | 5% | 5% | 4% | 3%* |

| Poverty level (2014)2 | ||||

| Less than 100% | 10% | 8% | 19%* | 18%* |

| 100-199% FPL | 22% | 21% | 29%* | 30%* |

| Supplemental coverage3 | ||||

| Medicare Advantage | 28% | 26% | 29% | 45%* |

| Medicaid | 15% | 11% | 28%* | 22%* |

| Employer-sponsored | 28% | 32% | 20% | 14%* |

| Medigap | 14% | 17% | 3%* | 4%* |

| Other | 1% | 1% | 1% | 1% |

| None | 14% | 13% | 19%* | 14% |

| Prescription drug coverage | ||||

| Enrolled in Part D | 57% | 55% | 66%* | 71%* |

| Enrolled in Part D with Low Income Subsidy (LIS) | 23% | 17% | 46%* | 38%* |

| NOTE: 1Sample includes all beneficiaries, including those who are enrolled for the entire year, those who become eligible during the year, and those who die during the year. 2Poverty estimates are for adults ages 65 and over during 2014. 3Supplemental coverage was assigned in the following order: 1) Medicare Advantage, 2) Medicaid, 3) employer-sponsored, 4) Medigap, 5) other public/private coverage, 6) no supplemental coverage. FPL is federal poverty level. *denotes statistically significant differences at the 95% confidence level from whites.

SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey Cost and Use File, 2011; 2014 poverty rates from March 2015 Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement. |

||||

| Table 3: Selected Measures of Health Status and Prevalence of Diseases/Chronic Conditions Among Medicare Beneficiaries, By Race/Ethnicity, 2011 | ||||

| Measure | Total | White | Black | Hispanic |

| Number of beneficiaries1 | 50 million | 38.2 million | 4.7 million | 4.5 million |

| Self-reported health status | ||||

| Excellent/very good/good | 73% | 76% | 63%* | 64%* |

| Fair/poor | 27% | 24% | 37%* | 36%* |

| Activities of daily living (ADLs)2 | ||||

| One or more | 35% | 34% | 41%* | 36% |

| Cognitive/mental impairment3 | 31% | 29% | 34% | 37%* |

| Number of chronic conditions4 | ||||

| Less than 3 | 34% | 34% | 37% | 35% |

| 3-4 | 39% | 39% | 39% | 40% |

| 5+ | 27% | 27% | 24%* | 25% |

| Diseases/chronic conditions | ||||

| Alzheimer’s disease | 7% | 7% | 8% | 9%* |

| Arthritis | 55% | 55% | 53% | 54% |

| Cancer (non-skin) | 18% | 19% | 13%* | 16%* |

| Depression | 28% | 27% | 26% | 35%* |

| Diabetes | 26% | 23% | 38%* | 38%* |

| Heart condition5 | 39% | 41% | 34%* | 32%* |

| Heart disease | 10% | 11% | 8%* | 9% |

| Heart failure | 8% | 8% | 9% | 6% |

| Hypertension | 68% | 66% | 79%* | 73%* |

| Mental condition6 | 31% | 30% | 31% | 38%* |

| Myocardial Infarction | 12% | 13% | 10%* | 11% |

| Osteoporosis/broken hip | 22% | 23% | 13%* | 20% |

| Parkinson’s disease | 1% | 2% | N/A | 1% |

| Pulmonary condition | 20% | 20% | 19% | 17% |

| Stroke | 11% | 10% | 14%* | 12% |

| NOTE: 1Sample includes all beneficiaries, including those who are enrolled for the entire year, those who become eligible during the year, and those who die during the year. 2Activities of daily living are eating, dressing, getting into and out of bed or chair, taking a bath or shower, using the toilet, and difficulty walking. 3Cognitive/mental impairment is defined as presence of memory loss that interferes with daily activity, difficulty making decisions, trouble concentrating, and loss of interest within the past year. 4The count for chronic conditions includes diagnosis with Alzheimer’s disease, arthritis, diabetes, emphysema, hypertension, osteoporosis, Parkinson’s disease, pulmonary disease, skin cancer, non-skin cancer, stroke, incontinence, broken hip, and/or angina, chronic heart disease and other mental conditions. 5Heart condition is defined as diagnosis with hardening of arteries, angina, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and/or problem with heart valves or heart rhythm or other heart disease. 6Mental condition is defined as presence of a mental disorder (excluding depression), mental retardation, depression, schizophrenia, and/or manic depression. *denotes statistically significant differences at the 95% confidence level from whites. N/A: estimates with relative standard errors greater than 30% are not provided and often correspond to low sample size.

SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey Cost and Use File, 2011. |

||||

| Table 4: Selected Measures of Access to Care Among Medicare Beneficiaries, by Race/Ethnicity, 2013 | ||||

| Measure | Total | White | Black | Hispanic |

| Number of beneficiaries1 | 48.9 million | 3606 million | 4.7 million | 4.6 million |

| Have a usual source of care | 95% | 96% | 94% | 92%* |

| No usual source of care | 5% | 4% | 6% | 8%* |

| Had trouble getting needed care | 6% | 5% | 7%* | 9%* |

| Had a health problem but did not see the doctor about it | 11% | 10% | 12% | 11% |

| Delayed care due to cost | 11% | 10% | 12% | 13% |

| Average doctor wait time (days) | 10.2 | 10.1 | 8.3 | 11.1 |

| Average ER wait time (mins) | 46 | 40 | 67* | 61* |

| Ease of getting to doctor | ||||

| Very satisfied | 39% | 42% | 30%* | 30%* |

| Satisfied | 54% | 52% | 64%* | 60%* |

| Dissatisfied | 4% | 4% | 4% | 6%* |

| Very dissatisfied | 1% | 1% | 1% | 2% |

| No experience | 2% | 2% | 2% | 2% |

| Satisfied with the quality of care received | ||||

| Very satisfied/satisfied | 94% | 95% | 93%* | 93%* |

| Dissatisfied/very dissatisfied | 3% | 3% | 5%* | 5%* |

| No experience | 2% | 2% | 2% | 3% |

| Ever been a resident/patient in a nursing home | 7% | 7% | 8% | 5%* |

| NOTE: 1Sample includes only those beneficiaries who are enrolled for the entire year. *denotes statistically significant differences at the 95% confidence level from whites.

SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey Access to Care File, 2013. |

||||

| Table 5: Selected Measures of Service Utilization by Traditional Medicare Beneficiaries, by Race/Ethnicity and Self-reported Health Status, 2011 | ||||||||||||

| Measure | Total | White | Black | Hispanic | ||||||||

| Number of beneficiaries1 | 36.1 million | 28.3 million | 3.3 million | 2.5 million | ||||||||

| Self-reported health status | Total | Exc./ Very good/ good |

Fair/ poor | Total | Exc./ Very good/ good |

Fair/ poor | Total | Exc./ Very good/ good |

Fair/ poor | Total | Exc./ Very good/ good |

Fair/ poor |

| 1+ inpatient stays | 19% | 14% | 30% | 19% | 15% | 31% | 21% | 14% | 33% | 15%* | 8%* | 25% |

| 2+ inpatient stays | 7% | 4% | 13% | 6% | 4% | 13% | 10%* | 5% | 18%* | 6% | N/A | 13% |

| Physician office visit | 78% | 77% | 79% | 80% | 80% | 81% | 71%* | 66%* | 77% | 68%* | 65%* | 74% |

| Any hospice days | 2% | 1% | 5% | 2% | 1% | 6% | 2% | N/A | N/A | 2% | N/A | N/A |

| 1+ SNF stays | 5% | 3% | 10% | 5% | 3% | 11% | 5% | N/A | 10% | 2%* | N/A | N/A |

| 1+ ED visits | 29% | 23% | 44% | 28% | 22% | 44% | 37%* | 30%* | 47% | 29% | 22% | 40% |

| 2+ ED visits | 12% | 8% | 23% | 12% | 8% | 23% | 19%* | 14%* | 26% | 11% | 7% | 19% |

| Any Rx events | 90% | 91% | 87% | 90% | 91% | 86% | 89% | 91% | 86% | 88% | 86% | 90% |

| Any dental events | 43% | 49% | 28% | 47% | 52% | 31% | 27%* | 30%* | 22%* | 30%* | 36%* | 22% |

| NOTE: 1 Sample includes all beneficiaries, including those who are enrolled for the entire year, those who become eligible during the year, and those who die during the year. Analysis excludes beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage. *denotes statistically significant differences at the 95% confidence level from whites. Excludes beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage. Exc. is excellent. SNF is skilled nursing facility. ED is emergency department. Rx is prescription drug. N/A: estimates with relative standard errors greater than 30% are not provided and often correspond to low sample size.

SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey Cost and Use File, 2011. |

||||||||||||

Endnotes

Issue Brief

Introduction

P. Reynolds, "The Federal Government's Use of Title VI and Medicare to Racially Integrate Hospitals in the United States, 1963 through 1967," American Journal of Public Health, 87(11):1850-1858, November 1997.

P. Lee, "Battling for the Right Health Policy, Then and Now," Generations, 39(2):15-20, Summer 2015.

Kaiser Family Foundation, "The Story of Medicare: A Timeline," May 2015, available at: https://www.kff.org/medicare/video/the-story-of-medicare-a-timeline/.

C. James, “Medicare and Minority Communities: Reflections on 50 Years of Progress and a Vision for the Future,” Generations, 29(2): 58-66, Summer 2015.

U.S. Centers for Disease Control, National Center for Health Statistics, Health, United States, 2014, Table 16: “Life expectancy at birth, age 65, and at age 75, by sex, race, and Hispanic origin: United States, selected years 1900-2013, available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus14.pdf#016.

R. Williams, “Medicare and Communities of Color,” National Academy of Social Insurance, No.11: November 2004.

M. Gornick, “A Decade of Research on Disparities in Medicare Utilization: Lessons for the Health and Health Care of Vulnerable Men,” The American Journal of Public Health, 98 (Suppl 1): S162-S168, September 2008.

S. Joshi et al, “Disparities among Blacks, Hispanics, and Whites in Time from Starting Dialysis to Kidney Transplant Waitlisting,” Transplantation, 95(2):309-18, January 2013.

M. Halpern, “Disparities in Timeliness of Care for U.S. Medicare Patients Diagnosed with Cancer,” Curr Oncol, 19(6):e404-e413, December 2012.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), “Medicare Hospital Readmission Among Minority Populations: 2007-2013 Trends and Disparities,” Winter 2015, available at: https://www.cms.gov/About-CMS/Agency-Information/OMH/Downloads/OMH_Dwnld-MedicareHospitalReadmissionsAmongMinorityPopulations.pdf.

K. Joynt et al, “Thirty-day Readmission Rates for Medicare Beneficiaries by Race and Site of Care,” JAMA, 305(7): 675-681, February 2011.

J. Ayanian, B. Landon, J. Newhouse, and A. Zaslavsky, “Racial and Ethnic Disparities among Enrollees in Medicare Advantage Plans,” The New England Journal of Medicine, 371(24): 2288-2297, December 2014.

A. Trivedi, A. Zaslavsky, E. Schneider, and J. Ayanian, “Trends in Quality of Care and Racial Disparities in Medicare Managed Care,” The New England Journal of Medicine, 353(7):692-700, August 2005.

E. Schneider, A. Zaslavsky, and A. Epstein, “Racial Disparities in the Quality of Care for Enrollees in Medicare Managed Care,” JAMA, 287(10):1228-1294, March 2002.

S. Wallace, “Equity and Social Determinants of Health Among Older Adults,” Generations, 38(4): 6-11, Winter 2014-2015.

G. Jacobson, J. Huang, T. Neuman, and K. Smith, “Wide Disparities in Income and Assets of People on Medicare by Race and Ethnicity,” Kaiser Family Foundation, September 2013, available at: https://www.kff.org/medicare/report/wide-disparities-in-the-income-and-assets-of-people-on-medicare-by-race-and-ethnicity-now-and-in-the-future/.

K. Schulman et al, “The Effect of Race and Sex on Physicians’ Recommendations for Cardiac Catheterization,” N Engl J Med, 340(8):618-626, February 1999.

P. Bach et al, “Primary Care Physicians Who Treat Blacks and Whites,” JAMA, 351(6):575-584, August 2004.

Y. Li et al, “Nursing Staffing Hours at Nursing Homes with High Concentrations of Minority Residents, 2001-2011,” Health Affairs, 34(12):2132-2134, December 2015.

A. Barnato et al, “Hospital-level Racial Disparities in Acute Myocardial Infarction Treatment and Outcomes,” Med Care: 43(4): 308–319, April 2005.

J. Skinner, “Racial, Ethnic, and Geographic Disparities in Rates of Knee Arthroplasty among Medicare Patients,” N Engl J Med, 349(14):1350-9, October 2003.

R. Weech-Maldonado et al, “Language and Regional Differences in Evaluations of Medicare Managed Care by Hispanics,” Health Services Research, 43(2):552-568, April 2008.

N. Ponce et al, “Language Barriers to Health Care Access among Medicare Beneficiaries,” Inquiry, 43(1):66-76, Spring 2006.

R. Valdez et al, A Profile of Hispanic Elders, Horizons Project: Nationwide Demographic Report, Health Care Financing Administration, May 2000, available at: http://latino.si.edu/virtualgallery/growingold/Nationwide%20Demographic.pdf.

M. Heckler, The Heckler Report: Report of the Secretary’s Task Force on Black and Minority Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Minority Health, 1985, available at: https://archive.org/details/reportofsecretar00usde.

Institute of Medicine, Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, National Academies Press, 2002.

National Academy of Social Insurance, “Strengthening Medicare’s Role in Reducing Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities,” Medicare Brief No. 16, October 2006, available at: https://www.nasi.org/usr_doc/Medicare_Brief_No_016.pdf.

CMS, The CMS Equity Plan for Improving Quality in Medicare, September 2015, available at: https://www.cms.gov/About-CMS/Agency-Information/OMH/OMH_Dwnld-CMS_EquityPlanforMedicare_090615.pdf.

CMS, Guide to Preventing Readmissions among Racially and Ethnically Diverse Medicare Beneficiaries, January 2016, available at: https://www.cms.gov/About-CMS/Agency-Information/OMH/Downloads/OMH_Readmissions_Guide.pdf.

M. Boutaugh et al, “Closing the Disparity Gap: The Work of the Administration on Aging,” Generations, 38(4):107-118, Winter 2014-2015.

C. James, “Medicare and Minority Communities: Reflections on 50 Years of Progress and a Vision for the Future.”

Chartpack

Categories sum to more than 100% because Hispanics may be of any race.

R. Hummer and M. Hayward, "Hispanic Older Adult Health and Longevity in the United States: Current Patterns and Concerns for the Future.” Daedalus, 144(2):20-30, Spring 2015.

J. Lariscy et al, “Hispanic Older Adult Mortality in the United States: New Estimates and an Assessment of Factors Shaping the Hispanic Paradox,” Demography, 52(1):1-14, February 2015.

M. Hayward et al, “Does the Hispanic Paradox in U.S. Adult Mortality Extend to Disability?” Population Research and Policy, 33(1):81-96, February 2014.

For additional information about the official poverty measure and the SPM, both developed by the U.S. Census Bureau, and poverty rates among seniors, see J. Cubanski, G. Casillas, and A. Damico, "Poverty Among Seniors: An Updated Analysis of National and State Level Poverty Rates Under the Official and Supplemental Poverty Measures," Kaiser Family Foundation, June 2015, available at: https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/poverty-among-seniors-an-updated-analysis-of-national-and-state-level-poverty-rates-under-the-official-and-supplemental-poverty-measures/.

Income takes into account Social Security, pensions, earnings, and other income sources; including income from assets, rental income, and retirement account (IRA) withdrawals. Income is presented on a per person basis; for married people income is divided equally between spouses to calculate per capita income. For additional information, see G. Jacobson, C. Swoope, T. Neuman, and K. Smith, "Income and Assets of Medicare Beneficiaries, 2014–2030," Kaiser Family Foundation, September 2015, available at: https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/income-and-assets-of-medicare-beneficiaries-2014-2030/.

Total savings includes retirement account holdings (such as IRAs or 401Ks) and other financial assets, including savings accounts, bonds and stocks. Savings are presented on a per person basis; for married people, savings are divided equally between spouses to calculate per capita savings. For additional information, see G. Jacobson et al, "Income and Assets of Medicare Beneficiaries, 2014–2030."

CMS, 2011 Health and Health Care of the Medicare Population, Table 2.4: "Self-Reported Health Conditions and Risk Factors of Medicare Beneficiaries, by Race/Ethnicity and Age, 2011."

T. Neuman, G. Casillas, and G. Jacobson, “Medicare Advantage and Traditional Medicare: Is the Balance Tipping?” Kaiser Family Foundation, October 2015, available at: https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-advantage-and-traditional-medicare-is-the-balance-tipping/

Similarly, the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) also finds lower shares of black and Hispanic beneficiaries reporting that they had seen or talked to a dentist in the past year compared with whites; see Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, Health, United States, 2014, Table 84: “Dental visits in the past year, by selected characteristics: United States, selected years 1997-2013,” available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus14.pdf.

Kaiser Family Foundation, “Oral Health and Medicare Beneficiaries: Coverage, Out-of-Pocket Spending, and Unmet Need," June 2012, available at: https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/oral-health-and-medicare-beneficiaries-coverage-out/.

CMS, “Medicare Hospital Readmission Among Minority Populations: 2007-2013 Trends and Disparities."

K. Joynt et al, “Thirty-day Readmission Rates for Medicare Beneficiaries by Race and Site of Care.”

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, Health, United States, 2014, Table 76: "Use of mammography among women aged 40 and over, by selected characteristics: United States, selected years 1987–2013," available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus14.pdf.