Modifying Medicare's Benefit Design: What's the Impact on Beneficiaries and Spending?

Proposals to modify the benefit design of traditional Medicare have been frequently raised in federal budget and Medicare reform discussions, including in the June 2016 House Republican health plan as part of a broader set of proposed changes to Medicare.1 Typically, benefit design proposals include a single deductible for Medicare Part A and B services, modified cost-sharing requirements, and a new annual cost-sharing limit, combined with restrictions on “first-dollar” Medigap coverage. Some proposals also include additional financial protections for low-income beneficiaries. Objectives of these proposals may include reducing federal spending, simplifying Medicare cost sharing, providing people in traditional Medicare with protection against catastrophic medical costs, providing low-income beneficiaries with additional financial protections, and reducing the need for beneficiaries to buy supplemental coverage.

This report examines the expected effects of four options to modify Medicare’s benefit design and restrict Medigap coverage, drawing on policy parameters put forth in recent years by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), and other organizations. For each option, we model the expected effects on out-of-pocket spending for beneficiaries in traditional Medicare, and assess how each option is expected to affect spending by the federal government, states, employers and other payers, assuming full implementation in 2018. The model is calibrated to CBO’s traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage 2018 enrollment projections. Details on data and methods are provided in the Appendix.

Option 1 would establish a single $650 deductible for Medicare Part A and Part B services, modify cost-sharing requirements, add an annual $6,700 cost-sharing limit to traditional Medicare, and limit the extent to which Medigap plans could cover the deductible. Option 2 aims to reduce the spending burden on beneficiaries relative to Option 1 by reducing the deductible to $400 and the cost-sharing limit to $4,000. Option 3 aims to provide additional financial protection to some low-income beneficiaries by providing them with full Medicare cost-sharing subsidies under the modified benefit design. Option 4 aims to make the modified benefit resign more progressive by income-relating the deductible and cost-sharing limit.

Key Findings

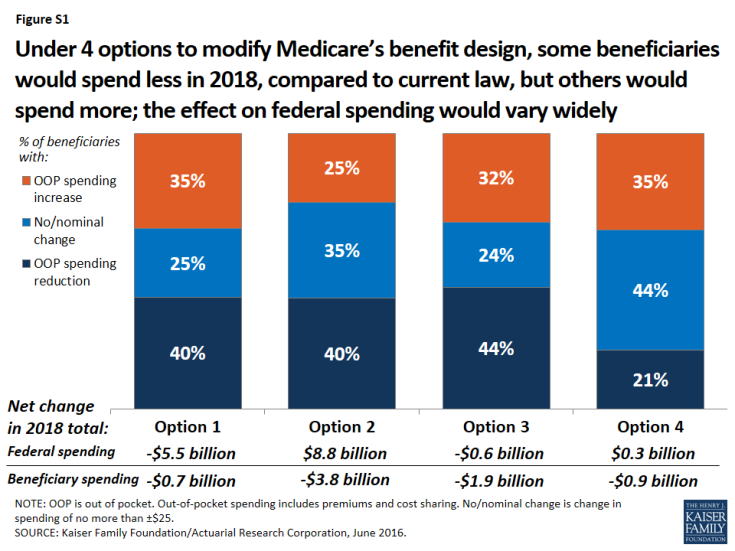

Proposals to modify the benefit design of traditional Medicare have the potential to decrease—or increase—federal spending and beneficiaries’ out-of-pocket spending, depending upon the specific features of each option (Figure S1). These options can be designed to maximize federal savings, limit the financial exposure of beneficiaries, or target relief to beneficiaries with low-incomes, but not simultaneously. Among the four options modeled, Option 1 is expected to produce the greatest federal savings (-$5.5 billion) but minimal aggregate savings for beneficiaries (-$0.7 billion), while exposing more than three million low-income beneficiaries to higher out-of-pocket costs, compared to current law. Conversely, Option 2 would provide greater financial protections and savings for beneficiaries, but result in a substantial increase in federal spending. And under each of the four options, some beneficiaries would be better off relative to current law, while others would not fare as well.

Figure S1: Under 4 options to modify Medicare’s benefit design, some beneficiaries would spend less in 2018, compared to current law, but others would spend more; the effect on federal spending would vary widely

- Modifying Medicare’s benefit design, with a single $650 Part A/B deductible, a new $6,700 cost-sharing limit, varying cost-sharing amounts, and restrictions on first-dollar Medigap coverage (Option 1) would reduce net federal spending by an estimated $5.5 billion and state Medicaid spending by $2.1 billion, with a more modest reduction of $0.7 billion in beneficiary spending in 2018. Just over one-third (35%) of beneficiaries would face higher costs under the modified benefit design, including 3.4 million beneficiaries with incomes below 150% of poverty,2 while 40% of beneficiaries in traditional Medicare would see savings.

- A similar approach, but with a lower deductible ($400) and cost-sharing limit ($4,000) (Option 2) would produce higher net savings for beneficiaries (-$3.8 billion) and for state Medicaid programs (-$3.8 billion) than Option 1, but would substantially increase net federal spending by an estimated $8.8 billion in 2018. A smaller share of beneficiaries would face spending increases compared to Option 1 (from 35% down to 25%).

- Fully subsidizing Medicare cost sharing for a subset of low-income beneficiaries (Option 3) would provide valuable financial help to some (but not all) low-income beneficiaries, but would eliminate nearly all the federal savings associated with the modified benefit design under Option 1. Compared to Option 1, a smaller share of low-income beneficiaries with incomes below 150% poverty would face higher out-of-pocket costs (from 36% down to 23%) and a larger share would face lower costs (from 25% up to 40%). This option would result in larger aggregate savings for beneficiaries than Option 1 (-$1.9 billion), but lower net federal savings (-$0.6 billion) and similar state Medicaid savings (-$2.0 billion) in 2018. As modeled, eligibility for subsidies under this option is narrowly defined (see page 3 for details) and only modestly improves upon existing subsidy programs for some low-income beneficiaries; expanding eligibility would help more low-income beneficiaries, but would also increase federal spending.

- Income-relating the deductible and cost-sharing limit (Option 4) would increase the progressivity of the modified benefit design, providing greater financial protection to beneficiaries with lower incomes and less financial protection to those with higher incomes. The lowest deductible and cost-sharing limit ($325 and $3,350, respectively) would apply to all traditional Medicare beneficiaries with incomes less than 150% of poverty, regardless of assets or supplemental coverage status, which results in a larger number of low-income beneficiaries receiving financial subsidies than under Option 3. Compared to Option 1, a smaller share of beneficiaries in traditional Medicare would see lower out-of-pocket costs in 2018 (from 40% down to 21%), even though more low-income beneficiaries would be helped. This option would reduce total beneficiary spending by an estimated $0.9 billion, while modestly increasing net federal spending by $0.3 billion in 2018 and reducing state Medicaid spending by $4.4 billion.

Conclusion

Our analysis shows that options to modify the benefit design of traditional Medicare combined with restrictions on first-dollar supplemental coverage vary widely in their impact on spending by the federal government, beneficiaries, and other payers. Aggregate changes in spending depend on the specific features of each option, including the level of the deductible and cost-sharing limit and whether additional financial protection is provided to low-income beneficiaries.

Some beneficiaries in traditional Medicare would be better off under each option than under current law, but others would not fare as well in a given year. The impact on beneficiaries’ out-of-pocket spending for premiums and cost sharing would depend on a number of factors, including beneficiaries’ use of services, whether or not they have supplemental coverage, and their incomes.

In general, adding a cost-sharing limit would provide valuable financial protection to a relatively small share of the Medicare population that incurs catastrophic expenses in any given year, although a larger share of beneficiaries would be helped by this provision over multiple years.3 Some beneficiaries could see savings due to lower premiums for Medicare and Medigap, but those without supplemental coverage may be more likely to incur higher spending because of cost-sharing increases.

Options designed to reduce the impact on out-of-pocket spending, whether for all beneficiaries in traditional Medicare or only for those with low incomes, can be expected to produce lower federal savings or could actually increase federal spending relative to current law. An income-related benefit design would be more progressive than if the same amounts applied to all beneficiaries regardless of income, and could be structured in a way to achieve aggregate savings for beneficiaries or the federal government, but at the same time, it would most certainly increase the complexity of the program for beneficiaries and program administrators.

Proposals to modify Medicare’s benefit design have the potential to produce federal savings, reduce aggregate beneficiary spending, and reduce spending by other payers, including spending by states on behalf of beneficiaries who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, and by employers who provide supplemental coverage to retirees. Such proposals could also simplify the program, provide beneficiaries with valuable protection against catastrophic expenses, add additional financial protections for low-income beneficiaries, and reduce the need for beneficiaries to purchase supplemental insurance. As this analysis demonstrates, however, it will be difficult for policymakers to achieve all of these ends simultaneously.