Seniors and Income Inequality: How Things Get Worse With Age

This was published as a Wall Street Journal Think Tank column on June 11, 2015.

Income inequality has been rising on the political agenda, yet one group has been left out of the discussion: seniors.

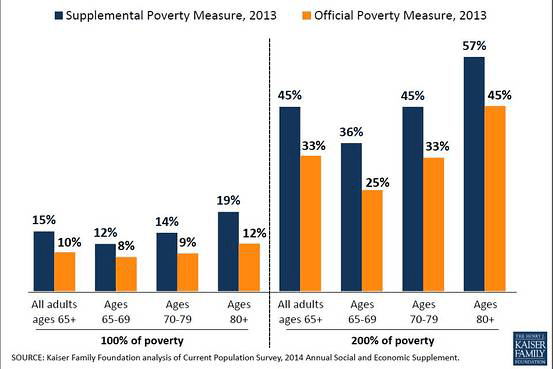

Older adults are somewhat less likely than working-age adults to be poor by the government’s traditional poverty measure, developed in the 1960s. But this official measure may understate the extent to which seniors live in poverty. Under a newer, alternative scale developed by the government in 2011, known as Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM), the rate of poverty among seniors is considerably higher. The SPM generally paints a fuller and more accurate picture, taking into account benefits that are ignored by the traditional measure, such as food stamps, as well as expenses such as tax liabilities or out-of-pocket health-care spending, in addition to geographic differences in the cost of living. And people on Medicare generally face higher health-care costs than younger adults.

The Kaiser Family Foundation’s latest research on SPM data, shown in the chart above, found that 15% of seniors live below the poverty line but 45% are living at two times the poverty level. And poverty among seniors increases as they age. Measured by the SPM, 36% of seniors ages 65 to 69 are at two times the poverty level but at age 80 or older the share rises to 57%. By contrast, the traditional, narrower government measure of poverty finds that 10% of seniors live under the poverty line, with still a third at two times the poverty level. Poverty rates for black and Hispanic seniors are substantially higher than for older white Americans, and the share of older women in poverty is higher than older men.

Income inequality at younger ages is carried into old age, when it is often too late to significantly alter earning power. But the high poverty rate for older seniors has implications for fine-tuning any future proposals to increase Medicare cost-sharing or to alter Social Security inflation adjustments. It would seem obvious that such plans would need to protect lower-income seniors. Many seniors may need more assistance, not less. As it stands, too many can barely scrape by.