Relatively Few Drugs Account for a Large Share of Medicare Prescription Drug Spending

Note: An updated analysis with more recent data is available here.

Policymakers are once again focusing attention on proposals to lower prescription drug costs. During the previous session of Congress, the House passed legislation (H.R. 3) to allow the federal government to negotiate drug prices for Medicare Part D, Medicare’s outpatient prescription drug benefit, and private insurers. Under H.R. 3, the HHS Secretary would negotiate prices for up to 250 brand-name drugs lacking generic or biosimilar competition with the highest net spending. In contrast, other drug price negotiation proposals placed no limit on the number of covered drugs subject to negotiation. In a similar vein, the Trump administration issued a final rule to establish a model through the CMS Innovation Center that would base Medicare’s payment for the 50 highest-spending Part B drugs (i.e., drugs administered by physicians in outpatient settings) on the lowest price paid by certain other similar countries. (In light of pending litigation, the Biden Administration has stated that it will not implement this model without further rulemaking.)

These drug pricing proposals raise the question of whether limiting the number of drugs subject to government price negotiation or international reference pricing might leave substantial savings on the table, even if this approach is more administratively feasible than subjecting all drugs to negotiation or reference pricing. This analysis provides context for this question by measuring the share of total Medicare Part D and Part B drug spending accounted for by top-selling drugs covered under each part. For this analyses, we ranked drugs by total spending in 2019, based on data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Medicare Part D and Part B drug spending dashboards. For Part D, we calculated estimates of net total spending, taking into account average rebates reported by the Congressional Budget Office. (See Data and Methods for details.)

Takeaways

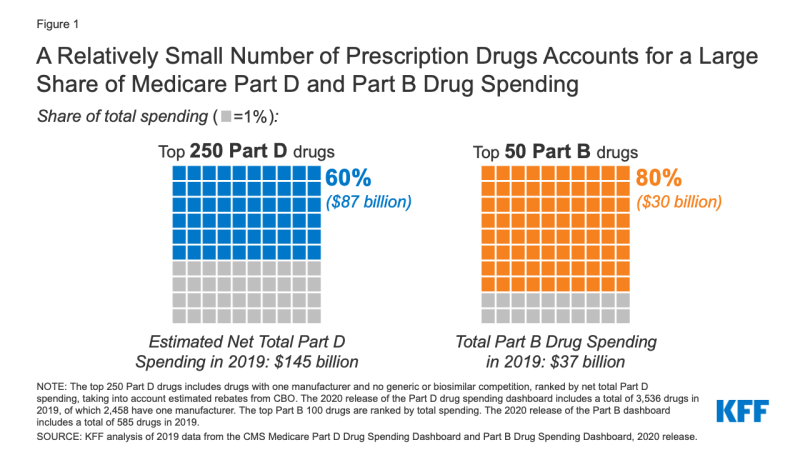

Our analysis finds that a relatively small number and share of drugs accounted for a disproportionate share of Medicare Part B and Part D prescription drug spending in 2019 (Figure 1).

- The 250 top-selling drugs in Medicare Part D with one manufacturer and no generic or biosimilar competition (7% of all Part D covered drugs) accounted for 60% of net total Part D spending.

- The top 50 drugs covered under Medicare Part B (8.5% of all Part B covered drugs) accounted for 80% of total Part B drug spending.

Medicare Part D

In 2019, Medicare Part D covered more than 3,500 prescription drug products, with total spending of $183 billion, not accounting for rebates. Because drug-specific rebate data are not publicly available, we applied average rebates from a CBO analysis of prices for top-selling brand-name drugs to derive an estimate of net Medicare Part D spending of $145 billion in 2019. For specialty drugs (which we identified as drugs with prices at or above $670 per claim, based on the amount of the Part D specialty tier threshold ]in 2019), we applied a rebate of 12%, and for non-specialty brand-name drugs, we applied a rebate of 47%. We assumed no rebate for lower-cost generic drugs.

Our analysis shows that Part D drug spending is concentrated among a relatively small number of drugs with only one manufacturer and no generic or biosimilar competition.

- The top-selling 250 drugs with one manufacturer and no generic or biosimilar competitors accounted for 60% of net total Part D spending in 2019 (Figure 1). In contrast, the remaining 2,208 drugs with one manufacturer accounted for 13% of net total Part D spending in 2019, and all other covered Part D drugs (1,078) accounted for 27% of net total spending.

- The average net cost per claim across the top 250 drugs with one manufacturer and no generic or biosimilar competitors was substantially higher than the average net cost per claim of other covered Part D drugs. For the top 250 drugs, the average net cost per claim was $5,750, more than twice as much as the average net cost per claim for the remaining 2,208 drugs with one manufacturer ($2,555), and more than 13 times greater than the average net cost per claim for all other covered Part D drugs ($422) (primarily generic drugs).

- The 10 top-selling Part D covered drugs with no generic or biosimilar competition in 2019 accounted for 0.3% of all covered products but 16% of net total Part D spending that year (Figure 2). These 10 top-selling drugs include three cancer medications, four diabetes medications, two anticoagulants, and one rheumatoid arthritis treatment (Table 1). Our estimate of net total spending on each of these drugs ranged from around $1 billion to $4 billion in 2019, based on average rebates for specialty and non-specialty brand drugs derived from CBO’s analysis.

Medicare Part B

Medicare Part B covers prescription drugs administered by physicians and other providers in outpatient settings. Part B covers a substantially smaller number of drugs than Part D – fewer than 600 drug products in 2019, with total spending of $37 billion – but many Part B covered drugs are relatively costly medications. As is the case under Part D, drug spending under Part B is highly concentrated among a handful of medications:

- The top 50 drugs ranked by total spending accounted for 80% of total Medicare Part B drug spending in 2019, while the top 100 drugs accounted for 93% of the total (Figure 3). In contrast, the remaining 485 covered Part B drugs accounted for only 7% of total Part B drug spending in 2019.

- The top 10 Part B covered drugs in 2019 accounted for 2% of all covered products but 43% of total Part B drug spending that year. The top 10 drugs include four cancer medications, two medications for macular degeneration, two rheumatoid arthritis treatments, one osteoporosis drug, and one bone marrow stimulant. Total spending on these drugs ranged from $2.9 billion for Eylea, a treatment for macular degeneration, to $0.9 billion for Remicade, a treatment for rheumatoid arthritis (Table 2)

Conclusion

Some recent proposals to lower prescription drug prices have limited the number of drugs subject to price negotiation and international reference pricing. This analysis shows that Medicare Part D and Part B spending is highly concentrated among a relatively small share of covered drugs, mainly those without generic or biosimilar competitors. Focusing drug price negotiation or reference pricing on a subset of drugs that account for a disproportionate share of spending would be an efficient use of administrative resources, though it would also leave some potential savings on the table. In considering whether to broaden these proposals to focus on all prescription drugs, policymakers may want to consider whether doing so would achieve sufficient savings to justify the added administrative burden and associated costs.

This work was supported in part by Arnold Ventures.

We value our funders. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.

| Methods |

| This analysis is based on 2019 data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Medicare Part B and Part D Drug Spending Dashboards. For Part B, the data includes spending for beneficiaries in traditional Medicare but not Medicare Advantage, because claims data are not available for beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage plans. For Part D, the data includes spending for beneficiaries in both traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage who are enrolled in Medicare Part D plans.

Drug spending metrics for Part B drugs presented in the dashboard represent the full value of the product, including the Medicare payment and beneficiary liability. Medicare reimbursement for most Part B drugs is 106% of the Average Sales Price (ASP) which is the average price to all non-federal purchasers in the United States and includes volume discounts, prompt pay discounts, cash discounts, free goods that are contingent on any purchase requirement, chargebacks (other than chargebacks for 340B discounts), and rebates (other than rebates under the Medicaid drug rebate program). For Part B covered drugs, beneficiaries are liable for 20% coinsurance. For this analysis, we sorted the list of drugs in the Part B dashboard in 2019 (n=585) by total spending, calculated the percent of total spending accounted for by each drug, and summed across the top 10, 25, 50, and 100 drugs ranked by total spending. Because Part B spending reported in the dashboard reflects the actual Medicare payment, no adjustment for rebates was necessary. Drug spending metrics for Part D drugs presented in the CMS dashboard are based on the gross drug cost, which represents total spending for the prescription claim, including Medicare, plan, and beneficiary payments. The Part D spending metrics do not reflect manufacturer rebates or other price concessions, because CMS is prohibited from publicly disclosing such information. In order to base our analysis on net drug spending, we incorporated average rebate estimates from an analysis of brand-name drug prices conducted by the Congressional Budget Office of Part D spending data. Based on CBO’s analysis of the difference between average retail and net prices for top-selling drugs, specialty drug rebates average 12% and non-specialty brand drug rebates average 47%. We applied the 12% rebate to gross drug spending amounts for drugs with average cost per claim above $670 (the threshold for inclusion of a drug on a Part D plan specialty tier in 2019), and the 47% rebate to gross drug spending amounts for all other drugs with one or two manufacturers where the brand name and generic name in the drug spending dashboard were not the same (which we interpreted as indicating a generic drug, along with multiple manufacturers). For drugs with three or more manufacturers, which generally corresponds to generic medications, we applied no rebate. Lack of publicly-available drug-specific rebate data limits our ability to further refine these estimates of net spending. While our estimates of net spending and the specific shares accounted for by different subsets of drugs would vary somewhat if we assumed different rebate amounts, the top-line finding – that a small number and share of drugs accounts for a large share of total spending – would not change. We then sorted the list of drugs in the Part D dashboard in 2019 (n=3,536) by net total spending (after adjusting for estimated rebates as described above) and number of manufacturers, sorting out drugs with one manufacturer that had no generic or biosimilar competitors, and calculated the percent of net total spending accounted for by each drug, summing across the top 10, 50, 100, and 250 drugs with one manufacturer and no generic or biosimilar competition ranked by net total spending. For the subsets of the top 250 drugs, all other drugs with one manufacturer, and all other covered Part D drugs, we also calculated the average net spending per claim based on the average spending per claim metric presented in the dashboard. |