Medigap Enrollment Among New Medicare Beneficiaries: How Many 65-Year Olds Enroll In Plans With First-Dollar Coverage?

Over the past several years, policymakers have considered a variety of proposals to discourage or prohibit people on Medicare from purchasing first-dollar supplemental insurance, often in the context of deficit and debt reduction efforts. 1 On March 26, 2015, the House of Representatives passed H.R. 2, the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015, which would replace the Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) formula, among other changes; the bill is currently pending in the U.S. Senate. H.R. 2 includes a provision that would prohibit Medicare supplemental insurance (Medigap) policies from covering the Part B deductible for people who become eligible for Medicare on or after January 1, 2020.2 This provision is designed to make future Medigap purchasers more price-sensitive when it comes to medical care, which could lead to a reduction in the use of health services and Medicare spending. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has estimated that the Medigap provision in H.R.2 would reduce federal spending by about $400 million between 2020 and 2025.3

To help cover Medicare’s cost-sharing requirements, most people on Medicare have some source of coverage that supplements Medicare, including Medigap policies (23%), employer or union-sponsored retiree health plans (35%), and Medicaid for individuals with low-incomes (19%).4 The two most popular Medigap policies are plans C and F, which are the only standard Medigap plans that cover the Part B deductible. In addition, a growing share of Medicare beneficiaries are covered under Medicare Advantage plans (about 30%), which often provide first-dollar coverage. H.R. 2 would restrict first-dollar coverage for Medigap policies, but not other sources of supplemental coverage, such as retiree health plans or Medicare Advantage.

This data note looks at the number and share of “new” Medicare beneficiaries who would be affected by the Medigap provision in H.R. 2, if it had been implemented in 2010, using the most current data sources available, and examines trends in Medigap enrollment among new beneficiaries since 2000.5

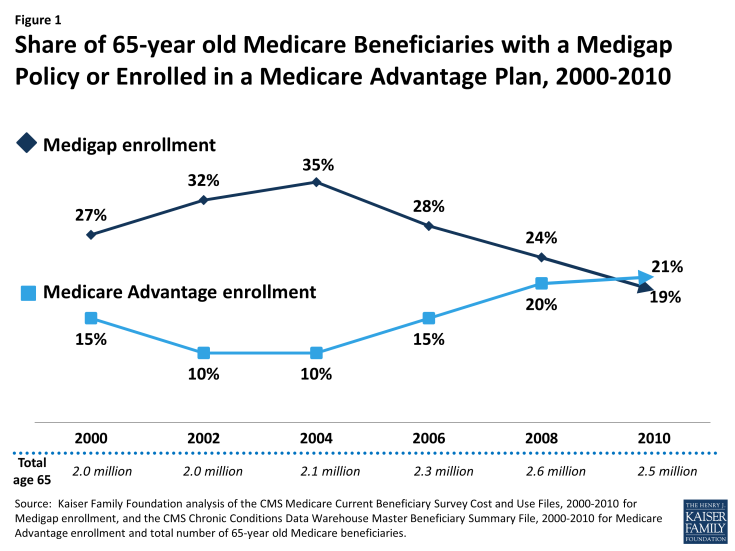

Figure 1: Share of 65-year old Medicare Beneficiaries with a Medigap Policy or Enrolled in a Medicare Advantage Plan, 2000-2010

Key Findings

- About one-fifth (19%) of 65-year old beneficiaries, or about 500,000 beneficiaries, purchased a Medigap policy in 2010 (Figure 1).

- In 2010, about half (53%) of all Medigap enrollees had plan C or plan F, which cover the Part B deductible.6 If this estimate were applied to the 65-year olds who purchased a Medigap policy in 2010, it would imply that approximately 10 percent of all 65-year old beneficiaries, or 250,000 beneficiaries, that year were enrolled in plan C or plan F. With each new cohort of 65-year old beneficiaries, more people would be affected by the provision, if seniors continued to purchase Medigap plans.

- Between 2004 and 2010, the number and share of 65-year old beneficiaries purchasing a Medigap policy steadily declined from 35 to 19 percent. If current trends continue, a smaller share of 65-year old beneficiaries in 2020 than in 2010 would be expected to purchase a Medigap policy (and would be potentially affected by the Medigap provision in H.R. 2).

- As Medigap enrollment declined between 2004 and 2010, Medicare Advantage enrollment increased among 65-year old beneficiaries, eclipsing Medigap enrollment by 2010.

- If the restriction on first dollar Part B coverage were applied to all Medigap policyholders with plan C or plan F (not limited to “new” beneficiaries as it is in H.R. 2), 12 percent of all Medicare beneficiaries, or about 4.9 million people would have been affected by this provision, if implemented in 2010.

Discussion

The Medigap provision in H.R. 2, as passed by the House of Representatives, would prohibit beneficiaries eligible for Medicare in 2020 or later years from purchasing a Medigap policy that covers the Part B deductible. If this policy had been implemented in 2010, it would have affected Medigap coverage for roughly 10 percent of all 65-year old Medicare beneficiaries. Based on declining Medigap enrollment trends among 65-year olds, a smaller share of new Medicare beneficiaries can be expected to be affected by this policy in the future.

Proposals that prohibit first-dollar Medigap coverage are projected to reduce Medicare spending, primarily because higher up-front costs are expected to result in beneficiaries using fewer services – both necessary and unnecessary services.7 Conversely, beneficiaries with supplemental coverage tend to use more Medicare-covered services and incur higher Medicare costs than beneficiaries without supplemental coverage, according to several studies.8

Restrictions on first-dollar supplemental coverage could make Medigap a more attractive option for beneficiaries if insurers reduce Medigap premiums because the plans cover a smaller share of claims.9 Another possibility is that the absence of first-dollar Part B coverage could make Medigap somewhat less attractive, and create an incentive for newly eligible beneficiaries to enroll in a Medicare Advantage plan instead. However, Medigap plans with restrictions on first-dollar coverage could remain an appealing option for other reasons. For example, Medigap insurers generally coordinate payments to providers and minimize the paperwork burden of medical claims for beneficiaries. Medigap policies also help to shield beneficiaries from sudden, out-of-pocket costs resulting from an unpredictable medical event and allow beneficiaries to more accurately budget their health care expenses.

During the period between 2004 and 2010, the share of new 65-year old beneficiaries choosing Medigap declined while the share opting for Medicare Advantage rose, suggesting that new beneficiaries may regard Medicare Advantage plans as a substitute for Medigap plans (coupled with traditional Medicare). New restrictions on Medigap coverage could potentially accelerate the growth in Medicare Advantage enrollment that has been occurring since 2004, particularly because relatively few beneficiaries change their source of coverage once they choose between traditional Medicare (with a supplement) and Medicare Advantage.10

The effects for Medicare beneficiaries who choose to purchase a Medigap policy without first-dollar Part B deductible could be expected to vary from one person to the next. For some, the Part B deductible (projected to be $185 in 2020)11 may not pose much of a barrier to care, but for others, particularly those with relatively low incomes, restrictions on first-dollar coverage could lead them to forgo both unnecessary and necessary services, potentially resulting in the use of more high-cost, acute care services down the road. If the Medigap provision in H.R. 2 becomes law, then tracking its effects on beneficiaries’ coverage decisions and use of services could provide insights into the possible effects of other policies that have been proposed to further restrict first-dollar coverage and raise cost-sharing requirements.

Gretchen Jacobson and Tricia Neuman are with the Kaiser Family Foundation; and Anthony Damico is an independent consultant.

Endnotes

For a summary of the Medicare provisions in the President’s budget for fiscal year 2016, including the proposal regarding Medigap, see Kaiser Family Foundation, “Summary of Medicare Provisions in the President’s Budget for Fiscal Year 2016,” February 2015. Available at: https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/summary-of-medicare-provisions-in-the-presidents-budget-for-fiscal-year-2016/ For a summary of other recent Medigap proposals and recommendations, see Kaiser Family Foundation, “Medigap Reform: Setting the Context for Understanding Recent Proposals,” January 2014. Available at: https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medigap-reform-setting-the-context/

Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015, H.R. 2, 114th Congress (2015).

Congressional Budget Office (CBO), “Cost Estimate and Supplemental Analyses for H.R. 2, as posted on the website of the House Committee on Rules on March 24, 2015,” March 25, 2015. The Office of the Actuary of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services estimated that the Medigap provision in H.R. 2 would reduce Part B spending by $600 million (or $450 million reduction in Part B spending net of premium offset) between 2020 and 2025. See Office of the Actuary of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “Estimated Financial Effects of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (H.R. 2),” April 9, 2015. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Research/ActuarialStudies/2015-HR2.html

See Kaiser Family Foundation, “Medigap Reform: Setting the Context for Understanding Recent Proposals,” January 2014. Available at: https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medigap-reform-setting-the-context/

This data note relies on data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) Cost and Use files for information about Medigap enrollment among 65-year old beneficiaries from 2000 to 2010. It uses data from the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) for information about the percent of Medigap enrollees in plans C or F. It also uses the CMS Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse Master Beneficiary Summary File including 5 percent of Medicare beneficiaries for information about the percent of 65-year old beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans from 2000 to 2010.

This estimate uses data from the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) for information about the percent of Medigap enrollees in plans C or F. For more information, see Kaiser Family Foundation, “Medigap Reform: Setting the Context for Understanding Recent Proposals,” January 2014. Available at: https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medigap-reform-setting-the-context/

For a review of the literature, see Swartz, K. December 2010. “Cost-sharing: Effects On Spending and Outcomes.” Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Research Synthesis Report No. 20. See also Lohr, K.N., R.H. Brook, C.J. Kamberg, et al. 1986. “Effect of Cost Sharing on Use of Medically Effective and Less Effective Care.” Medical Care 24(9, Supplement): S31-S38. See Capps C. and D. Dranove. “Intended and Unintended Consequences of a Prohibition on Medigap First-Dollar Benefits,” for America’s Health Insurance Plans, October 2011. Similarly, the NAIC has argued that focusing on Medigap as the driver of medical care use discourages the use of all care, in contrast to other reforms that would aim to incentivize the use of necessary and appropriate care. See National Association of Insurance Commissioners, Senior Issues Task Force, Medigap PPACA Subgroup, “Medicare Supplement Insurance First-Dollar Coverage and Cost Shares Discussion Paper,” October 31, 2011.

See, Hogan, C., “Exploring the Effects of Secondary Coverage on Medicare Spending for the Elderly.” Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, August 2014. Available at: http://medpac.gov/documents/contractor-reports/august2014_secondaryinsurance_contractor.pdf

See Merlis, M. “Medigap Reforms: Potential Effects of Benefit Restrictions on Medicare Spending and Beneficiary Costs,” Kaiser Family Foundation, July 2011. Available at: https://www.kff.org/medicare/report/potential-effects-of-medigap-reforms/

Jacobson G., Neuman P., and Damico A. 2015. “At Least Half of All Medicare Advantage Enrollees Had Switched From Traditional Medicare, 2006–11.” Health Affairs. 34(1): 48–55. Hoadley, J., Hargrave, E., Summer, L., et al. 2013. “To Switch or Not to Switch: Are Medicare Beneficiaries Switching Drug Plans to Save Money?” Kaiser Family Foundation, October 2013. Abaluck, J. and Gruber, J. 2013. “Evolving Choice Inconsistencies in Choice of Prescription Drug Insurance,” NBER Working Paper No. 19163, June 2013. Abaluck, J. and Gruber, J. 2011. “Choice Inconsistencies Among the Elderly: Evidence from Plan Choice in the Medicare Part D Program.” American Economic Review, 101(4): 1180-1210. Heiss, F., Leive, A., McFadden D., and Winter, J. 2012. “Plan Selection in Medicare Part D: Evidence from Administrative data,” NBER Working Paper No. 18166, June 2012. Zhou C. and Zhang, Y. 2012. “The Vast Majority of Medicare Part D Beneficiaries Still Don’t Choose the Cheapest Plans That Meet Their Medication Needs.” Health Affairs. 31(1): 2259-2265. Said, Q., King, A. J., Erickson, S. W., et al. 2015. “Self-Reported Plan Switching in Medicare Part D: 2006-2010.” American Journal of Pharmaceutical Benefits 6(6): e157-168. Ketcham, J. D., Lucarelli, C., and Powers, C. A. 2015. “Paying Attention Or Paying Too Much in Medicare Part D.” American Economic Review, 105(1): 204-33.

See Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Office of the Actuary, “2014 Annual Report of The Board of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medicare Insurance Trust Funds,” July 2014. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/ReportsTrustFunds/TrusteesReports.html