“What is CMMI?” and 11 other FAQs about the CMS Innovation Center

Q1: What is CMMI – the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation?

The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI), also known as the “Innovation Center,” was authorized under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and tasked with designing, implementing, and testing new health care payment models to address growing concerns about rising costs, quality of care, and inefficient spending. Congress specifically directed CMMI to focus on models that could potentially lower health care spending for Medicare, Medicaid, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) while maintaining or enhancing the quality of care furnished under these programs. CMMI is part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and is managed by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

Q2: How many new payment models has CMMI launched? How many patients and providers have been involved in CMMI models?

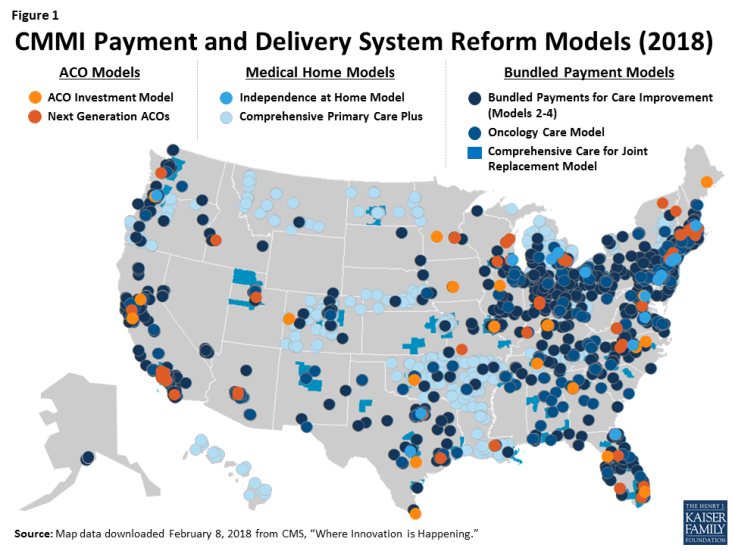

CMMI has launched over 40 new payment models, involving more than 18 million patients and 200,000 health care providers.1 Many of these models are in Medicare, including accountable care organizations (ACOs), bundled payment models, and medical homes models. Combined, these three types of models in Medicare are located in all 50 states and the District of Columbia (Figure 1). CMMI is also testing payment models in Medicaid and CHIP.2 Separately, CMMI awards grants to state agencies, researchers, and other organizations for projects to design and implement new payment models with the same goals of improving care and lowering costs. While the focus of CMMI is on Medicare, Medicaid, and CHIP programs, CMMI interventions also include multi-payer alignment models that affect patients with commercial insurance.

Q3: Is this type of work new for CMS?

No and yes. CMS has always had the authority to test payment models through demonstration programs. Through CMMI, however, the ACA granted the Secretary more tools and funding to design, adapt, and test models that could produce savings. Moreover, the Secretary now has broader authority to expand CMMI programs into Medicare, Medicaid, and CHIP if they meet savings and quality criteria, and terminate the models that fail. In prior years, Congressional action was necessary to expand successful demonstration programs into the full Medicare program, which often delayed or blocked their implementation. Additionally, CMS was often prevented from modifying or ending demonstration models based on early results (positive or negative), because the models were specified in law.

Q4: How (and how much) is CMMI funded?

The ACA funded CMMI $10 billion for the years 2011 through 2019, and allocated another $10 billion for CMMI each decade thereafter. These funds are not subject to annual appropriations. They are designated for the operation of CMMI and to test and evaluate health care payment models that have the specific goals of lowering program expenditures under Medicare, Medicaid, and CHIP while maintaining or enhancing the quality of care furnished under these programs.

Q5: Does CMMI cost or save federal dollars?

Both. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that in its initial years, CMMI had net spending due to start-up costs for launching new payment models, but in later years, CMMI will save the federal government an estimated $34 billion, on net, from 2017-2026. This savings projection takes into account about $12 billion in costs to implement the models and $45 billion in savings. CBO attributes a large part of CMMI savings to the Secretary’s ability to end payment models that fail to produce savings and expand CMMI models that do produce savings.

Q6: What is the evidence on Medicare savings and quality among CMMI models and other delivery system reforms?

To date, the evidence on Medicare payment and delivery system reforms is mixed. While some CMMI models are meeting and improving upon quality goals, overall net savings to Medicare has been relatively modest, with large variations in results between the major models as well as among the individual programs within each of them. Below are the latest available results for selected models.

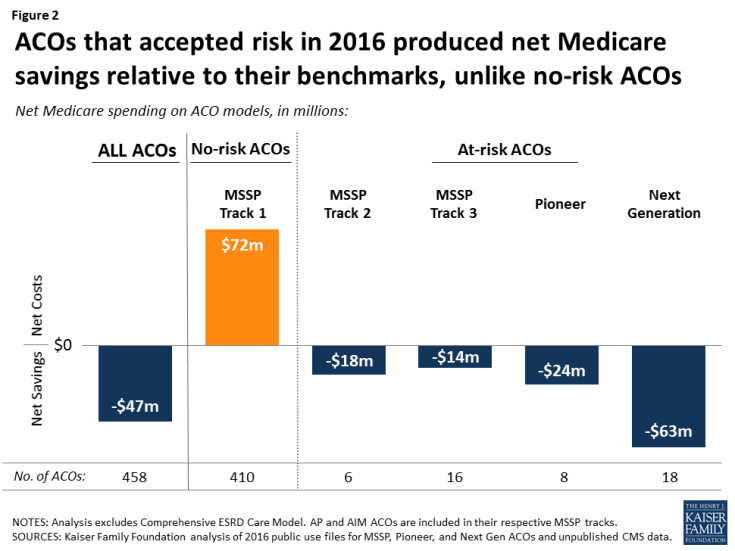

- Across accountable care organizations (ACOs)—including ACO programs that CMS runs either through CMMI or outside of CMMI—net savings to Medicare totaled $47 million in 2016 relative to CMS’s target (“benchmark”) levels, after accounting for shared savings and losses (Figure 2).3 Models that required ACOs to be at financial risk for their total spending achieved net Medicare savings, while in contrast, models with no-risk (“bonus only”) generated net Medicare costs. Despite the financial incentives for savings for ACOs, there have been no notable differences in quality between traditional Medicare and ACOs.4

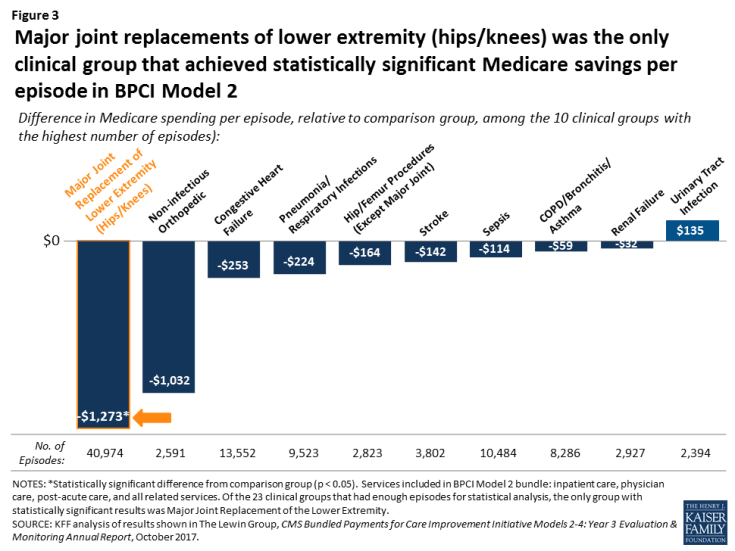

- Results from a voluntary bundled payment model show that the clinical episode with the most potential for Medicare savings has been hip/knee replacements, saving an average of $1,273 per episode in 2015, without notable quality differences from a comparison group (Figure 3).5 Spending results on later bundled payment models are unavailable.

- Most medical home models had lower Medicare spending on covered services, but incurred net costs to Medicare after accounting for care management fees. Overall, quality scores for medical homes were generally similar to matched comparison groups.6

For further details on these results, see the Kaiser Family Foundation Evidence Link—an online resource with interactive tools for comparing each model based on key features and available evidence on savings and quality.

Q7: Have any CMMI models been successful enough to be eligible to become a full part of Medicare?

Yes. Two CMMI models have met the statutory criteria to be eligible for expansion by reducing program spending while preserving or enhancing quality. These two models are the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) model and the Pioneer ACO model. The DPP was implemented in partnership with the YMCA with a focus on Medicare beneficiaries at high risk of developing type 2 diabetes. The model concentrated on patient engagement activities for losing weight and making positive dietary choices. Based on the DPP’s savings of $2,650 per person and its demonstration of quality improvements, the Secretary expanded this program to become a full preventive benefit in Medicare Part B (the “Medicare Diabetes Prevention Program”), effective April 2018.

The Secretary also certified the Pioneer ACO model for expansion into Medicare based on early savings and quality results. The model was extended an extra year, but to date, the Secretary has not made the Pioneer ACO model a part of the full Medicare program.7

Q8: Do people in Medicare know they are in a CMMI model? Can they opt-out or opt-in?

Sometimes, depending on the model. For most of the CMMI models, doctors and other providers are required to inform their Medicare patients if they are participating in a CMMI payment model, but it is not clear if their patients are typically aware of their attribution to one, or the implications for their care.

Most beneficiaries in CMMI models are in traditional Medicare and, therefore, retain their right to see any Medicare provider without financial penalty. Beneficiaries in CMMI models can also sign certain forms to prevent the sharing of their health information with other providers. To avoid being in a CMMI model altogether, Medicare beneficiaries would need to seek care from doctors and providers who are not participating in the model.8

In contrast, if beneficiaries want to be part of a specific ACO, they may submit information to CMS to indicate their preference, based on who they identify as their main doctor. CMMI is currently implementing this “voluntary alignment” method across ACOs, and Congress established it as a requirement in the recently passed Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018. This law also allows risk-bearing ACOs to pay their Medicare patients $20 per primary care service as an incentive for obtaining primary care in their ACO. This incentive could have the indirect effect of increasing Medicare beneficiaries’ awareness of their alignment with a particular ACO.

Q9: Do CMMI models include enrollees in Medicare Advantage plans?

While most of CMMI’s Medicare models apply only to traditional Medicare, the Value-Based Insurance Design (VBID) model was created specifically for beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage plans with certain chronic conditions. The VBID model allows Medicare Advantage plans to offer lower cost sharing and/or additional benefits to encourage their use of “high value” services and providers. CMMI is currently testing the model in 10 states, and plans to expand to 25 states in 2019. In the recently passed Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, Congress further expanded the CMMI VBID model to allow participation among Medicare Advantage plans in all states by 2020.

In addition to the VBID model, CMS noted in its recent Request for Information (RFI) that the agency is considering new CMMI models that would include Medicare Advantage plan participation. Additionally, starting in 2019, physicians may count their affiliation with qualifying Medicare Advantage plans towards their eligibility for 5-percent bonuses under the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA), described further in Question #11.

Q10: Are Medicare Advantage plans the same as ACOs?

Some observers have noted similarities between Medicare Advantage plans and ACOs, particularly CMMI’s Next Generation ACO model, which allows ACOs to take on “full risk” for their attributed Medicare beneficiaries. However, several differences between Medicare Advantage plans and ACOs exist. For example, beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage plans are “locked in” to their plans until they are able switch during the annual Medicare open enrollment period, and may face high cost sharing or no coverage if they seek care from out-of-network providers. In contrast, beneficiaries in ACOs do not have physician networks and can see any Medicare providers without higher cost sharing.9

Q11: Will CMMI play a role in the new way that Medicare will be paying doctors?

Yes. Based on a law passed in 2015—the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA)—physicians who participate in certain CMMI models will be eligible for automatic 5-percent bonuses on their Medicare payments, starting in 2019. The CMMI models that qualify physicians for these bonuses are called “advanced alternative payment models” (advanced APMs). They include certain types of ACOs, certain bundled payment modes, and the Comprehensive Primary Care Plus (CPC+) medical home model.10 CMS estimated that for 2017, between 70,000 and 120,000 providers (under 10% of all Medicare clinicians billing Part B) will be affiliated with advanced APMs, but more are anticipated in future years as the number of advanced APMs continues to increase.

Q12: What changes has CMMI instituted since the start of the Trump Administration?

In general, CMMI’s organizational structure, funding, and many of CMMI’s models have continued along the same lines as under the previous Administration. In some cases, however, CMMI has changed or canceled certain models—particularly ones that specify mandatory participation among hospital providers—and has announced the start of a new bundled payment model in the fall of 2018, and the official start of the Medicare Diabetes Prevention Program in Part B.

- Effective January 1, 2018, CMS pared back the mandatory hospital participation requirement for a bundled payment model for hip/knee replacements that started in 2016—the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CJR) This model was initially mandatory for all hospitals in 67 designated areas of the country, but CMS made CJR participation voluntary for hospitals in half of the areas, as well as for all small and/or rural hospitals. CMS estimated that paring back the number of hospitals required to participate would lower total savings by $108 million.11

- Also effective January 1, 2018, CMS canceled several other CMMI models that had not been started, including mandatory CMMI bundled payment models that were designed under the previous Administration for conditions such as cardiac care and surgical hip and femur fractures.12

- On January 9, 2018, CMMI announced a voluntary bundled payment model (Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Advanced) to start in October 2018, building on current models.

- On February 2, 2018, CMS canceled the second of CMMI’s voluntary decision support models designed to test ways to engage Medicare patients in clinical decision-making. CMS canceled a related model on November 13, 2017. Both models were designed in 2016, but neither became active.13

- On February 9, 2018, Congress enacted several changes to CMMI models in the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018. These include expanding telehealth coverage for Medicare beneficiaries in certain ACOs; allowing ACOs to pay Medicare patients direct incentives for primary care (up to $20 per visit); and directing CMS to establish procedures for self-alignment to ACOs. Additionally, the Act extended CMMI’s Independence at Home (IAH) model, which focuses on home-based team care for frail seniors and expanded CMMI’s Value-Based Insurance Design (VBID) model in Medicare Advantage as described in Question #9.

- Effective April 9, 2018, Medicare Part B will include the Medicare Diabetes Prevention Program, which stems from an earlier CMMI model that achieved savings, as described in Question #7.

Endnotes

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, CMS Innovation Center: Report to Congress, December 2016; Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services' FY 2018 performance budget for Congressional Justification. The count of models includes new models introduced since the 2016 Report to Congress was released.

See for example, Artiga, S., E. Hinton, and R. Rudowitz, “Current Flexibility in Medicaid: An Overview of Federal Standards and State Options,” Kaiser Family Foundation, January 2017.

Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of Accountable Care Organization Public Use Files: Shared Savings Program PUFs, 2013-2016 and Pioneer ACO PUFs, 2012-2016. Analysis includes MSSP ACOs that are managed outside of CMMI.

MedPAC, “Accountable Care Organization Payment Systems,” revised October 2016.

LewinGroup, CMS Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiative Models 2-4: Year 3 Evaluation & Monitoring Annual Report, October 2017.

Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of “Comprehensive Primary Care (CPC) Initiative 2016 Shared Savings & Quality Results,” September 2017;

RAND Corporation, Evaluation of CMS’s Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) Avanced Primary Care Practice (APCP) Demonstration: Final Report, September 2016;

RTI International, Evaluation of the Multi-Payer Advanced Primary Care Practice (MAPCP) Demonstration, June 2017;

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “Independence at Home Demonstration Corrected Performance Year 2 Results,” January 2017.

Although the Secretary has not made Pioneer ACOs a part of Medicare, other ACO models that similarly require participants to take on financial risk are now offered as part of the Medicare Shared Savings Program ACOs.

However, a beneficiary who is in a hospital in a mandatory area will not be able to find a hospital not participating – unless they can access a small or rural hospital.

In some cases, beneficiaries may receive “incentive payments” when they receive primary care services from providers in their ACO.

Models qualifying as Advanced APMs: MSSP Track 2 and Track 1+ ACOs, Next Generation ACOs, and future MSSP Track 1+ ACOs, CJR, BPCI Advanced, and CPC+ models.

Canceled models include Episode Payment Models (Acute Myocardial Infarction model, Coronary Artery Bypass Graft model, and Surgical Hip and Femur Fracture Treatment model) and the Cardiac Rehabilitation Incentive Payment model.

These two models were the Direct Decision Support (DDS) Model, canceled February 2, 2018 and the Shared Decision Making (SDM) Model, canceled November 13, 2017. The designs for both models were initiated in 2016.