Medicaid Beneficiaries Who Need Home and Community-Based Services: Supporting Independent Living and Community Integration

Introduction

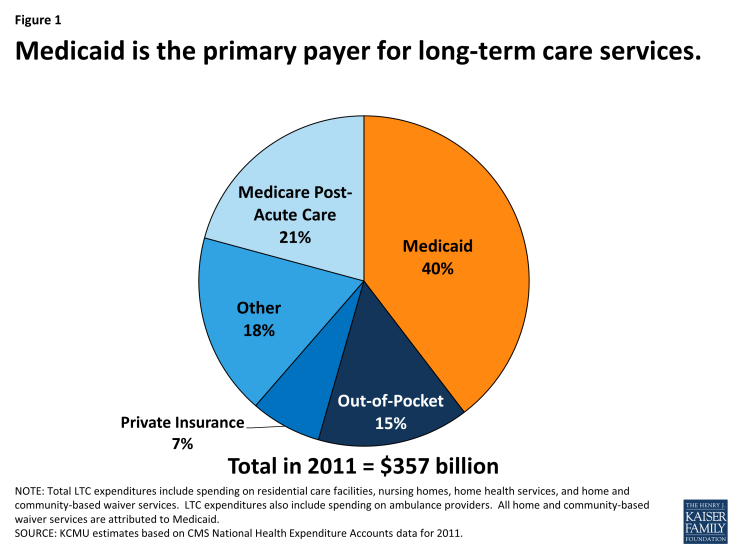

Medicaid is an important source of health insurance for seniors and people with disabilities. In addition to covering a variety of medical care, such as doctor visits, behavioral health services, and prescription drugs, Medicaid also is the primary payer for long-term services and supports (LTSS), including nursing facility care and home and community-based services (HCBS) (Figure 1).1 HCBS provide assistance with activities of daily living (such as eating, bathing, and dressing) and instrumental activities of daily living (such as preparing meals and housecleaning) for people with physical or cognitive functional limitations that result from age or disability. HCBS include a range of benefits, such as residential services, adult day health care programs, home health aide services, personal care services, and case management services, among others.2 HCBS may be delivered through a self-directed service model in which beneficiaries select, train, and dismiss their providers and/or control the allocation of funds among particular services in their individual budgets.3

To provide insight into the unique experiences of Medicaid beneficiaries who need HCBS, this report profiles nine seniors and people with disabilities residing in Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Louisiana, North Carolina, and Tennessee.4 They include people with a range of developmental disabilities, such as autism and intellectual disabilities; physical disabilities, such as cerebral palsy and multiple sclerosis; multiple chronic health conditions; Alzheimer’s disease and aging-related dementia, and physical functional limitations associated with the aging process. Based on a series of telephone interviews conducted in 2013 by the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, these profiles illustrate how beneficiaries’ finances, employment status, relationships, well-being, independence, and ability to interact with the communities in which they live – in addition to their health care – are affected by their Medicaid coverage and the essential role of HCBS in their daily lives. We extend our appreciation to the beneficiaries and their families who so generously took the time to share their stories.

Background

Nearly 3.2 million people received Medicaid HCBS in 2010, with expenditures totaling $52.7 billion.5 Historically, the Medicaid program has had a structural bias toward institutional care because state Medicaid programs must cover nursing facility services, whereas most HCBS are provided at state option.6 While states can choose to offer HCBS as Medicaid state plan benefits, the majority of HCBS are provided through waivers.7 Unlike Medicaid state plan benefits, which must be available to all beneficiaries as medically necessary, waiver enrollment can be capped, resulting in waiting lists when the number of people seeking services exceeds the amount of available funding. In 2012, nearly 524,000 people were on HCBS wavier waiting lists nationally, with the average waiting time exceeding two years; waiting lists vary both across states and within states among waiver target populations.8

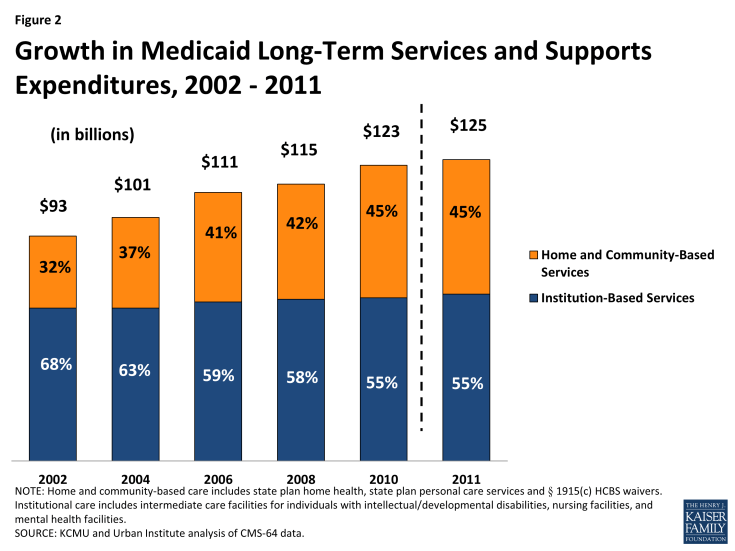

Over the last several decades, states have been working to rebalance their long-term care systems by devoting a greater proportion of spending to HCBS instead of institutional care. These efforts are driven by beneficiary preferences for HCBS, the increased population of seniors and people with disabilities who need HCBS, and the fact that HCBS typically are less expensive than comparable institutional care. The U.S. Supreme Court’s 1999 Olmstead decision, finding that the unjustified institutionalization of people with disabilities violates the Americans with Disabilities Act, also has heightened the state and federal focus on community integration efforts.9 While the majority of Medicaid LTSS spending still goes toward institutional care, the proportion of Medicaid LTSS spending on HCBS continues to increase relative to spending on institutional services. In FY 2011, HCBS accounted for 45 percent of total Medicaid LTSS spending nationally, up from 32 percent in FY 2002 (Figure 2).

Key Themes

The nine Medicaid beneficiaries profiled in this report illustrate the diversity of medical conditions, personal circumstances, and needs for services and supports among seniors and people with disabilities who rely on HCBS. At the same time, their stories suggest some common themes underlying the important role of Medicaid HCBS in their lives:

- Medicaid HCBS increase independent living and community integration opportunities for seniors and people with disabilities. The beneficiaries profiled in this report uniformly express their desire to increase or maintain their independence to the maximum extent possible and emphasize the vital role of Medicaid HCBS in enabling them to do so. Mary B., a senior with dementia, was able to move from a facility to an apartment where Medicaid provides the home health aide services and medical supplies necessary to support her safely at home while her daughter is at work. Margot, a woman with cerebral palsy, and Mary A., a senior with physical functional limitations, both valued the increased independence they experienced when they were able to have their aides accompany them in the community to assist with grocery shopping and errands. Beneficiaries who have spent time waiting for services describe the transformative impact that receiving HCBS has had on their quality of life. Curtis, a young man with developmental disabilities, is now improving his independent living skills and participating in the community in an age-appropriate manner with the support of Medicaid attendant care services. Nicholas, an adult with multiple sclerosis, hopes to receive a car attachment to transport his power wheelchair as a Medicaid home and community-based waiver service, which will decrease the barriers he faces in physically accessing the community.

- Medicaid HCBS support people with disabilities who work. Several of the beneficiaries profiled in this report are working or are able and want to be employed, and Medicaid HCBS play an important role in supporting these efforts by ensuring that beneficiaries’ daily self-care and functional needs are met. Mark, a man with autism, is proud of his job as a grocery store courtesy clerk, a position that he has held for a dozen years; a group home placement would ensure that he will continue to have the necessary self-care supports that he needs to continue working as his aging parents become less able to provide for his daily needs. Margot, a woman with a master’s degree in social work, wants to be employed and could do so with sufficient home health aide hours to manage her daily physical needs as a result of functional limitations due to cerebral palsy. Aubrey, a teenager with autism, improved his social interaction and independent living skills with the help of Medicaid HCBS to the extent that he now is enrolled in college and majoring in mechanical drafting.

- Medicaid HCBS fill needs of seniors and people with disabilities that would otherwise go unmet due to beneficiaries’ limited financial resources. The profiles relate the struggles of people with low incomes trying to pay out-of-pocket for costly services while facing the competing demands of paying for housing, food, and other necessities. Patricia, a woman with multiple chronic conditions, and Mary A., a senior with physical functional limitations, both need assistance with cooking, cleaning, and grocery shopping so that they can continue to live independently in their homes. Patricia worries about her susceptibility to falling, and Mary A. needs help with bathing and dressing. At various points, both women have tried to pay out-of-pocket for services but have been unable to do so on a sustained basis on budgets limited to Social Security benefits and food stamps.

- Medicaid HCBS play a vital role in ensuring a safe stable source of care because beneficiaries’ needs often outstrip the assistance that family and friends can provide. The beneficiaries profiled in this report receive a range of informal assistance from relatives and friends, which may not be a sustainable solution for people who need long-term HCBS or those with intense care needs. Families often provide a great deal of care, and beneficiaries and their caregivers report stress in meeting on-going or deteriorating needs for services and supports. Irene’s daughter moved cross-country to provide full-time care, but as Irene’s Alzheimer’s disease progresses, her needs are becoming too great for her daughter to handle alone. Curtis and Mark are adults with developmental disabilities whose need for constant supervision and supports is likely to outlast their parents’ ability to provide that care.

- Medicaid HCBS are cost-effective as a less expensive alternative to institutional care and as preventive care to avoid more expensive deteriorations in health status. Beneficiaries emphasize their preference to live in the community instead of a nursing home not only because they feel that community living improves their quality of life and independence but also as a cost-saving measure. They also cite examples of the role of HCBS in avoiding more costly inpatient hospitalizations and emergency room visits. Nicholas, who required emergency room treatment for injuries sustained during a fall while transferring from his wheelchair to the bathroom, hopes that a Medicaid HCBS waiver will provide home modifications to make his apartment physically accessible so that he can remain living there safely. Margot believes that some of her inpatient hospitalizations were potentially avoidable if she received additional home health aide services to address functional and self-care limitations resulting from cerebral palsy.

The stories presented in this report illustrate the time, energy, dedication, and patience required to obtain and coordinate the services necessary to ensure independent safe community living for seniors and people with disabilities. As a result of their experiences accessing HCBS, these individuals offer concrete ideas about how the system can be improved for others, such as:

- Simplifying the application process, which beneficiaries can find confusing and at times difficult to navigate. Specifically, beneficiaries envision a streamlined system through which seniors and people with disabilities can learn about and sign up at once for all of the various services that may be needed, including Medicaid HCBS, self-directed service options, subsidized housing, and transportation.

- Minimizing the number of times that applicants must “tell their story” and provide the same information again when seeking services.

- Providing easily accessible, accurate, timely updates about beneficiaries’ status, such as through a website, while waiting for services.

- Offering additional supports to beneficiaries who move inter-state to help navigate delays and additional barriers in arranging for the medically necessary care they need to transition to their new communities.

Despite some challenges, these stories confirm the essential role of Medicaid HCBS in improving beneficiaries’ daily lives by providing the physical and social functional supports necessary to access and benefit from community living. As these profiles make clear, seniors and people with disabilities have unique contributions to offer the communities in which they live, and Medicaid HCBS facilitate their integration into community life. For the beneficiaries profiled in this report and the many others who receive HCBS, Medicaid is a true safety net as it is often the only available source of these essential services to support community living.