How State Medicaid Programs are Managing Prescription Drug Costs: Results from a State Medicaid Pharmacy Survey for State Fiscal Years 2019 and 2020

Medicaid provides health coverage for millions of Americans, including many with substantial health needs who rely on Medicaid drug coverage for both acute problems and for managing ongoing chronic or disabling conditions. Though the pharmacy benefit is a state option, all states provide pharmacy benefit coverage. States administer the benefit in different ways but within federal guidelines regarding, for example, pricing, utilization management, and rebates. Due to federally required rebates, Medicaid pays substantially lower net prices for drugs than Medicare or private insurers. After a sharp spike in 2014 due to specialty drug costs and coverage expansion under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), Medicaid drug spending growth has slowed, similar to the overall US pattern; however, state policymakers remain concerned about Medicaid prescription drug spending as spending is expected to grow in future years. Due to Medicaid’s role in financing coverage for high-need populations, it pays for a disproportionate share of some high-cost specialty drugs. In addition, Medicaid is required to cover the “blockbuster” drugs increasingly entering the market as a result of the structure of the pharmacy benefit. Policymakers’ actions to control drug spending have implications for beneficiaries’ access to needed prescription drugs.

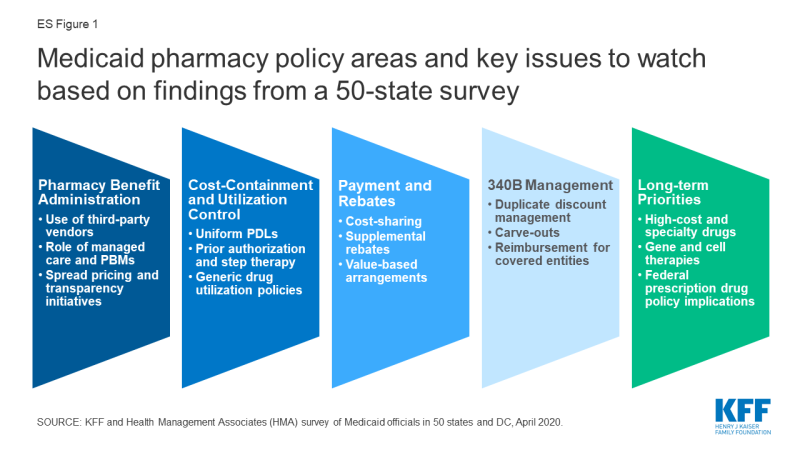

To better understand how the Medicaid pharmacy benefit is administered across the states, KFF and Health Management Associates conducted a survey of all 50 states and the District of Columbia (DC) in 2019. Highlights from the full survey are below (ES Figure 1).

Figure ES-1: Medicaid pharmacy policy areas and key issues to watch based on findings from a 50-state survey

What entities play a role in administering Medicaid pharmacy benefits?

States may administer the Medicaid pharmacy benefit on their own or may contract out one or more functions to other parties. The administration of the pharmacy benefit has evolved over time to include delivery through managed care organizations (MCOs) and increased reliance on pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs). In addition, drug utilization review (DUR) boards and pharmacy and therapeutics (P&T) committees play oversight and administrative roles in Medicaid pharmacy benefits.

All but one state reported outsourcing some or all functions to one or more vendors as of July 1, 2019. The most commonly outsourced functions reported were claims payment, utilization management, and drug utilization review. Of the 44 states that reported outsourcing the claims payment function, 23 reported that their fiscal intermediary processes pharmacy claims.

States are exploring pharmacy policy reforms to adapt to the growth in managed care and the growing role of pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs). States reported enacting or considering policy changes such as drug carve-outs, PBM pass-through pricing, and transparency reporting requirements. While most states that contract with MCOs reported that the pharmacy benefit was carved in to managed care coverage, two states reported plans to carve out the pharmacy benefit in FY 2020, one state has announced that a carve-out would be effective in FY 2021, and other states reported carve-outs were under consideration. Fifteen states also reported carving out one or more drugs or drug classes, often as part of a fiscal risk mitigation strategy.

States are taking action to prevent or monitor spread pricing within MCO-PBM contracts. State use of external vendors for administering the pharmacy benefit, particularly the use of pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), has generated considerable policy debate about costs and prices in Medicaid, particularly as it relates to oversight and regulation. Spread pricing refers to the difference between the payment the PBM receives from the MCO and the reimbursement amount it pays to the pharmacy. In the absence of oversight, some PBMs have been able to keep this “spread” as profit. As of July 1, 2019, 11 MCO states prohibited PBM spread pricing and five states reported plans to eliminate spread pricing in FY 2020. One state also reported that a spread pricing prohibition would take effect in January 2021. Twenty-six MCO states also reported they will have transparency reporting requirements in place in FY 2020.

How are states managing use and cost in their programs?

Managing the Medicaid prescription drug benefit and pharmacy expenditures remains a policy priority for state Medicaid programs, and state policymakers remain concerned about Medicaid prescription drug spending growth. Because state Medicaid programs are required to cover all drugs from manufacturers that have entered into a federal rebate agreement (in both managed care and FFS settings), states cannot limit the scope of covered drugs to control drug costs. Instead, states use an array of payment strategies and utilization controls to manage pharmacy expenditures.

Most states (46 of 50 reporting states) reported having a preferred drug list (PDL) in place for fee-for-service (FFS) prescriptions as of July 1, 2019. PDLs allow states to drive the use of lower cost drugs and offers incentives for providers to prescribe preferred drugs. In recent years, a growing number of MCO states have adopted uniform PDLs requiring all MCOs to cover the same drugs as the state. Sixteen MCO states reported having a uniform PDL for some or all classes and eight states plans to establish or expand a uniform PDL in FY 2020.

Most states reported that prior authorization (PA) was always (16 states) or sometimes (30 states) imposed on new drugs. Over two-thirds of the responding states (35) report reviewing comparative effectiveness studies when determining coverage criteria, and the vast majority of responding states (45 of 50) require biosimilar drugs to undergo the same review process as other drugs. While states often impose PA on high-cost specialty or non-preferred drugs, a number of states have legislation protecting drug classes or categories from the use of these tools in some or all circumstances.

How are states addressing payment for prescription drugs?

Medicaid payments for prescription drugs are determined by a complex set of policies at both the federal and state levels that draw on price benchmarks to set both ingredient costs and determine rebates under the federal Medicaid drug rebate program (MDRP). States set policies on dispensing fees paid to pharmacies and beneficiary cost-sharing within federal guidelines, while federal regulations guide payment levels for ingredient costs. The final cost to Medicaid is then offset by any rebates received under the federal MDRP. In addition, states or managed care plans may negotiate with manufacturers for supplemental rebates on prescription drugs or form multi-state purchasing pools when negotiating supplemental Medicaid rebates to increase their negotiating power.

Forty-six states report negotiating for supplemental rebates in addition to federal statutory rebates. Approximately two-thirds of these states (30 states) have entered into a multi-state purchasing pool to enhance their negotiating leverage and collections.

A small, but growing number of states are employing alternative payment methods to increase supplemental rebates through value-based arrangements (VBAs) negotiated with individual pharmaceutical manufacturers. States are pursuing these alternative payment methods as a response to high-cost, breakthrough therapies. Two states reported having a VBA in place as of July 1, 2019 and an additional eight states reported plans to submit a VBA State Plan Amendment to CMS or implement a VBA in FY 2020.

States reported a variety of strategies to avoid receiving duplicate discounts on 340B drugs dispensed by safety net providers. The 340B program offers discounted drugs to certain safety net providers that serve vulnerable or underserved populations, including Medicaid beneficiaries. States cannot receive Medicaid rebates for drugs acquired through the 340B program. Strategies to avoid duplicate discounts include relying on the Medicaid exclusion file, prohibiting contract pharmacies and using claims indicators.

States reported continued challenges related to new, expensive breakthrough drugs, particularly those approved on an accelerated pathway. More than two-thirds of the responding states reported that developing policies and strategies related to new high-cost therapies was a top priority. Because of the structure of the MDRP, states are required to cover all drugs approved by the FDA, even if the drug demonstrates limited clinical efficacy.

Looking ahead

States’ management of the pharmacy benefit in FYs 2019 and 2020 reflects efforts to respond to an increasingly changing prescription drug landscape within the flexibility of federal guidelines. Drug pricing has been prominent in national policy debates and lawmakers at both the state and federal levels continue to show interest in efforts to control costs that may have implications for the Medicaid program.

Federal prescription drug policy changes have implications for states. States reported concerns related to enacted legislation such as the SUPPORT and 21st Century Cures Acts as well as monitoring proposed federal statutory and regulatory efforts related to drug pricing, drug reimportation, gene and cell therapies, and PBM contracting reforms. Some federal efforts propose policy changes to Medicaid while others focus on Medicare and commercial insurance but may have implications for Medicaid.

States continue to explore MCO pharmacy policy reforms and view them as a high priority. State priorities include a focus on increasing oversight, implementing uniform PDLs and improving data collection related to managed care.

States remain concerned about prescription drug spending growth and continue to explore policies to ensure fiscal sustainability. States reported developing PA policies for gene and cell therapies, exploring value-based arrangements, and carving out high-cost drugs from managed care.