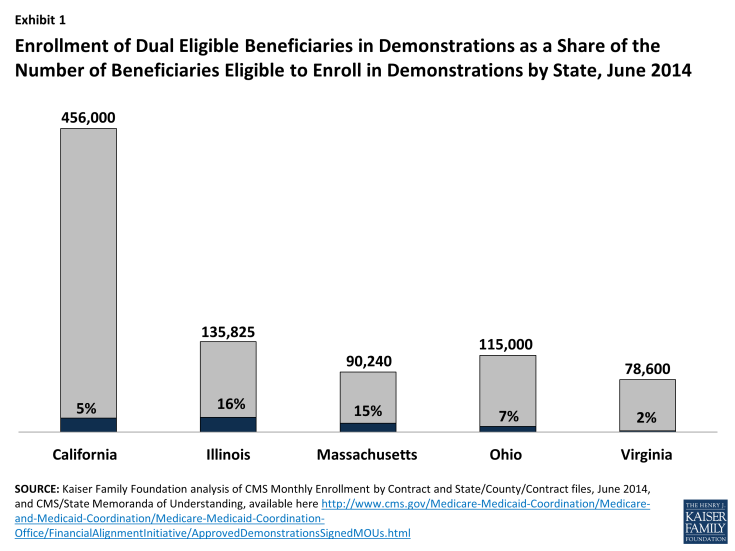

July 2014 marks a year since the first beneficiaries dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid began receiving services through one of the new financial alignment demonstrations. The demonstrations seek to maintain or decrease health care costs while maintaining or improving health outcomes for this vulnerable population of seniors and non-elderly people with significant disabilities. In 2011, CMS anticipated that the three year demonstrations would begin in 2012, and CMS has estimated that the demonstrations will serve no more than 2 million beneficiaries. To date, CMS has approved 13 demonstrations in which nearly 1.5 million beneficiaries in 12 states are eligible to enroll. As of June 2014, just over 66,000 beneficiaries were enrolled in a capitated demonstration health plan in California, Illinois, Massachusetts, Ohio, and Virginia (Exhibit 1), with enrollment to follow in other states through early 2015. At this early stage of implementation, some initial insights about the demonstrations are beginning to emerge:

Enrollment of Dual Eligible Beneficiaries in Demonstrations as a Share of the Number of Beneficiaries Eligible to Enroll in Demonstrations by State, June 2014

- Practical, On-the-Ground Considerations Merit Measured Approaches to Timeframes

Even though some time to design and plan the demonstrations was built into the implementation process, the work required before the demonstrations were ready to start enrolling and providing services to beneficiaries has taken longer than anticipated. Initial planning for the demonstrations began in earnest when CMS awarded state design contracts in 2011, and envisioned a target implementation date by the end of 2012. By the time that states submitted their demonstration proposals in June 2012, two states proposed implementing in 2012, while 13 were planning for 2013, and 11 anticipated 2014. Among the demonstrations approved to date, nearly every state has delayed enrollment to allow extra time for key tasks such as completing health plan readiness reviews, conducting outreach to beneficiaries and providers, establishing systems to “intelligently” assign beneficiaries to health plans in a way that preserves continuity of care during transitions, setting and risk adjusting payment rates, and building adequate provider networks. While not always a politically easy decision to make, delaying enrollment start dates has given CMS and states additional time needed to develop and implement the many policies and procedures needed to facilitate enrollment and deliver services through managed care arrangements. - New Partners, New Collaborations, New Metrics Present New Learning Curves

One opportunity presented by the demonstrations is the potential to better integrate and coordinate long-terms services and supports (LTSS) and behavioral health care with physical health care. The memoranda of understanding approving each state’s demonstration describe the care coordination that will occur both within the health plan care team through the person-centered planning process and between the health plan and other entities. For example, Ohio plans must contract with Area Agencies on Aging to coordinate home and community-based waiver service for beneficiaries over age 60, Michigan plans must contract with the prepaid inpatient health plans that provide behavioral health services, and California plans must coordinate with the county behavioral health agencies for specialty mental health services and with county social services agencies for in-home services and supports. Bringing these often siloed systems together will require change, learning, and the investment of resources on behalf of states, health plans, and providers. For example, demonstration health plan staff in Virginia recently observed that while they have case management experience, they are new to working in a managed care environment and experiencing a “steep. . . learning curve” with respect to administering LTSS. The development of quality measures for LTSS also remains an area where additional work is needed. The care coordination and service integration aspects of the demonstrations could have the potential to realize modest cost savings and improve beneficiary health outcomes, for example by reducing avoidable hospitalizations and emergency department visits and increasing the use of home and community-based services instead of institutional care. At the same time, delivery system change requires adequate planning and resource investment to ensure that necessary services are not disrupted, especially for beneficiaries who rely on LTSS to live independently in the community. - Each State’s Demonstration Is Unique, and It Will Be Some Time Before Evaluation Results Are Available

Analysis of the approved memoranda of understanding reveals that the demonstrations are diverse in many respects. Most states are testing capitated financial models through which services are delivered by private health plans, while others are testing managed fee-for-service models through which services are coordinated by entities such as Medicaid health homes (Washington) or accountable care organizations (Colorado). While Massachusetts targets non-elderly beneficiaries with disabilities, other states focus on both elderly and non-elderly beneficiaries or on specific sub-populations, such as people who use LTSS. Massachusetts’ demonstration also is unique in that it includes an independent living-LTSS coordinator as part of the beneficiary’s care team. Some states are including Medicaid home and community-based waiver services in their demonstrations, with various financial incentives to promote community-based care over institutionalization. The states’ demonstrations also are testing a range of methods of risk-adjusting the Medicaid portions of the capitated payment rates.�� Throughout the course of the demonstrations, state dissemination of information, through enrollment dashboards, early indicator, initial focus group, and monthly enrollment reports, and preliminary state-initiated evaluation findings, as well as CMS’s evaluation of the demonstrations (conducted by RTI International), will be important sources of information from which to derive and apply insights about how to improve care and control costs for these vulnerable beneficiaries. While CMS’s evaluation of the demonstrations calls for periodic reports, the first of which will be based on the initial six months of enrollment in each state, followed by quarterly, annual, and final reports, the evaluation plan does not specify which reports will be publicly available or in what timeframe. CMS’s evaluation plan also cautions that the analysis may be limited by the quality and timeliness of claims and encounter data. Consequently, complete information about the demonstrations’ impact is unlikely to be available in the near term.

The demonstrations will continue to develop over their three-year terms, during which additional insights will emerge. For example, it is still too early to determine the sources of program savings, whether the models will be financially viable over the long-term, or the demonstrations’ overall impact on access to and quality of care and health outcomes, all of which will be important elements in evaluating the demonstrations’ overall success. As additional states move toward implementation, they may be able to learn from earlier states’ implementation experiences. The Kaiser Family Foundation will continue to track these efforts and is conducting case studies in three early implementation states, Massachusetts, Ohio, and Virginia, to gather and disseminate additional early lessons from the demonstrations in the initial stages of implementation.