What is Medicaid's Impact on Access to Care, Health Outcomes, and Quality of Care? Setting the Record Straight on the Evidence

Julia Paradise and Rachel Garfield

Published:

Introduction

Medicaid, the nation’s main public health insurance program for low-income people, now covers over 65 million Americans – more than 1 in every 5 – at least some time during the year. The program’s beneficiaries include many of the most disadvantaged individuals and families in the U.S. in terms of poverty, poor health, and disability. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) provided for a broad expansion of Medicaid to cover millions of low-income uninsured adults whom the program has historically excluded. However, as a result of the Supreme Court’s decision on the ACA, the Medicaid expansion is, in effect, a state option. Almost half the states are moving forward with the Medicaid expansion. But the others, which are home to half the uninsured adults who could gain Medicaid coverage under the ACA, have decided not to expand Medicaid at this time or are still debating the issue.

Controversy about the Medicaid expansion has been stoked by an assertion that first appeared in a Wall Street Journal editorial a couple of years ago and has since resurfaced periodically, that “Medicaid is worse than no coverage at all.”1 2 3 4 5 6 This claim about Medicaid is sharply at odds with the authoritative findings of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) Committee on Consequences of Uninsurance, detailed in Care Without Coverage: Too Little, Too Late, the second of six reports the IOM issued on the subject in the early 2000’s.7 Based on a comprehensive review of the research examining the impact of health insurance on adults, the IOM charted the causal pathway from coverage to better health outcomes, concluding:

Health insurance coverage is associated with better health outcomes for adults. It is also associated with having a regular source of care and with greater and more appropriate use of health services. These factors, in turn, improve the likelihood of disease screening and early detection, the management of chronic illness, and effective treatment of acute conditions such as traumatic brain injury and heart attacks. The ultimate result is improved health outcomes.

In light of Medicaid’s large and growing coverage role, and the significant health care needs of its beneficiaries, an evidence-based assessment of the program’s impact on access to care, health outcomes, and quality of care is of major interest. Such an assessment would also be helpful given perennial concerns about insufficient physician participation in Medicaid, generally attributed to low fees paid by state Medicaid programs. Since Medicaid was established nearly 45 years ago, a large body of research on and analysis of the program has accumulated. After first reviewing the purpose of health insurance and the distinctive profile of the Medicaid population – both considerations that lend important context to the research findings – this brief takes a look at what the literature shows overall regarding the difference Medicaid makes.

Issue Brief

What is the purpose of health insurance?

The IOM articulated the purpose of health insurance in the first of its six reports: “For individuals and families, health insurance enhances access to health services and offers financial protection against high expenses that are relatively unlikely to be incurred as well as those that are more modest but are still not affordable to some.”1 Three points of elaboration help to explain the mechanisms of health insurance, and to highlight both its potential and its limits. First, health coverage helps to connect people with care, in many cases by linking them with a network of providers who participate in their health insurance plan. This is how managed care and preferred provider organizations work. Second, health insurance lowers financial barriers to access. It does this by reducing out-of-pocket costs for medical care, which disproportionately burden low-income people and people with extensive health care needs. Common measures of financial access to care (or lack thereof) include both delayed or forgone care or unmet needs due to cost, and medical cost burden, such as out-of-pocket expenses exceeding some threshold and rates of medical debt and medical bankruptcy.

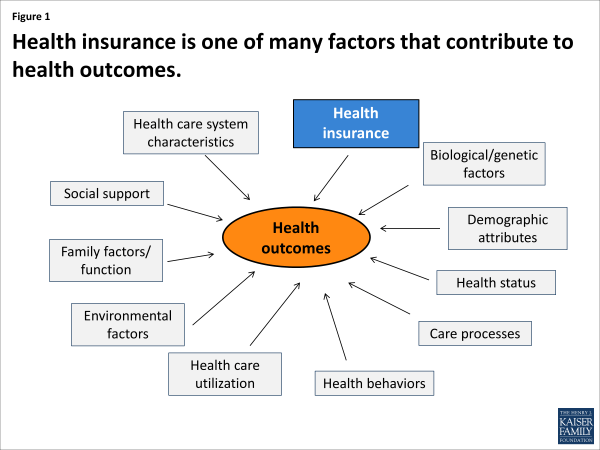

Finally, conceptual models of access and health have identified health insurance as one factor among many, including social, family, genetic, health care system factors and others, whose interaction determines how individuals and populations fare.2 Figure 1 provides a simplified illustration of just some of the variables at play. Given the complex influences involved in determining access, quality, and outcomes, expectations that health insurance alone can correct inadequacies in care or health disparities, are misplaced. Health insurance cannot overcome systemic barriers to access like health care workforce shortages in low-income communities, or the higher prevalence of chronic diseases in some populations. The impact of health insurance – whether public or private – needs to be considered in this broader context, and researchers and users of research must ask whether observed shortfalls in health care outcomes reflect failures of health insurance or the contribution of other factors that may call for different policy responses.

Who are Medicaid beneficiaries?

Medicaid was designed to provide health coverage for low-income children and families who lack access to private health insurance because of their limited finances, health status, and/or severe physical, mental health, intellectual, or developmental disabilities. Medicaid also assists low-income elderly and disabled Medicare beneficiaries with their Medicare premiums and cost-sharing and covers important benefits that Medicare does not cover, especially long-term care. Most states have expanded coverage for low-income children beyond federal minimum requirements so that children with family income up to at least 200% of the federal poverty level (FPL) are eligible for Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). [In 2013, 200%FPL was $47,100 for a family of four] However, state Medicaid eligibility standards for parents are far more restrictive and, in half the states, childless adults under age 65 – no matter how low their income – are ineligible for Medicaid unless they are disabled or pregnant. Thus, the adult populations studied in most Medicaid research are extremely poor.

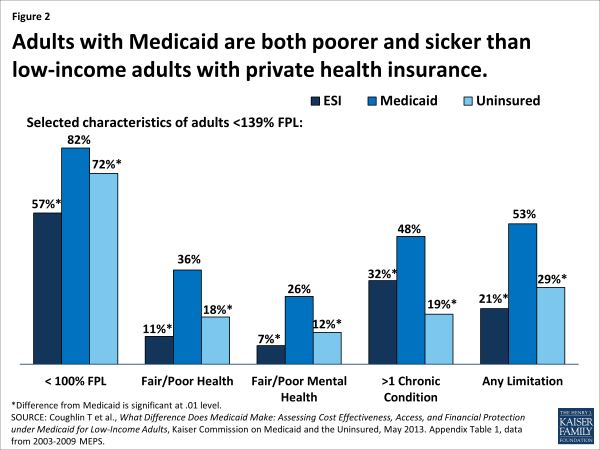

Because of Medicaid’s eligibility criteria and the strong correlation between poverty and poor health and disability, Medicaid beneficiaries are poorer and have a poorer health profile compared with both the privately insured and the uninsured. This is true even within the low-income population, as Figure 2 illustrates for adults. The distinctly higher rates of poverty, chronic illness, and disability in the Medicaid population are important to bear in mind when considering the evidence on Medicaid’s impact. These disadvantages make access and quality benchmarks that are based on the experience of the privately insured population more challenging to meet in Medicaid. Studies that control for observable differences between Medicaid and comparison populations provide a fairer assessment of the program’s impact on access and quality. Even so, researchers commonly cite as a limitation of their studies the possibility that they did not fully control for underlying population differences that might help to explain their findings. This limitation may be even more consequential in analyses that examine how health outcomes (as opposed to access or quality of care) compare between Medicaid beneficiaries and other populations, because a larger set of factors may attenuate the impact of health coverage on outcomes.

Finding #1: Having Medicaid is much better than being uninsured.

Consistently, research indicates that people with Medicaid coverage fare much better than their uninsured counterparts on diverse measures of access to care, utilization, and unmet need. A large body of evidence shows that, compared to low-income uninsured children, children enrolled in Medicaid are significantly more likely to have a usual source of care (USOC) and to receive well-child care, and significantly less likely to have unmet or delayed needs for medical care, dental care, and prescription drugs due to costs.3 4 5 6

The research findings on adults generally mirror the patterns for children. A synthesis of the literature on the impact of Medicaid expansions for pregnant women concluded, “…the weight of evidence is that expansions led to modest improvements in prenatal care use, in terms of either earlier prenatal care or more adequate prenatal care, at least in some states and for some groups affected by the expansions.”7 Mothers covered by Medicaid are much more likely than low-income uninsured mothers to have a USOC, a doctor visit, and a dental visit, and to receive cancer screening services.8 Nonelderly adults covered by Medicaid are more likely than uninsured adults to report health care visits overall and visits for specific types of services; they are also more likely to report timely care and less likely to delay or go without needed medical care because of costs.9 Projections from a recent analysis show that, if Medicaid beneficiaries were instead uninsured, they would be significantly less likely to have a USOC and much more likely to have unmet health care needs; except for emergency department care, their use of key types of services would also drop significantly. At the same time, their out-of-pocket spending would increase dramatically – almost four-fold on average.10 Other research provides evidence of increased access to care and health care utilization for previously uninsured low-income adults who gain Medicaid coverage under state expansions of eligibility.11

Recently, the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment has provided uniquely powerful evidence about the impact of Medicaid coverage on uninsured adults.12 13 14 The evidence is compelling because the study is a randomized controlled trial (RCT), the gold standard in research design. Taking advantage of a lottery held in Oregon in 2008 to allocate a limited number of new Medicaid “slots” for low-income, uninsured nonelderly adults, a team of researchers gathered data on access, utilization, and clinical health measures for both the adults who gained Medicaid through the lottery and the adults who did not. Two rounds of findings have been published in the New England Journal of Medicine, which can be summarized, in part, as follows:

- Medicaid increased access to care and health care use, and improved self-reported health. One year out from the lottery, the adults who gained Medicaid were 70% more likely to have a regular place of care and 55% more likely to have a regular doctor than the adults who did not gain coverage. Associated with more consistent primary care, Medicaid also increased the use of preventive care such as mammograms (by 60%) and cholesterol checks (by 20%), and the Medicaid adults had more outpatient visits and hospital admissions and used more prescription drugs. Finally, the researchers found that being covered by Medicaid increased self-reported health. Compared with the uninsured adults, the Medicaid adults were 25% more likely to report they were in good to excellent health (versus fair to poor health), 40% less likely to report health declines in the last six months, and 10% more likely to screen negative for depression. The findings two years out from the lottery confirmed that Medicaid coverage continued to be associated with increased access to care and health care use, and improved self-reported health.

- Medicaid improved adults’ mental health markedly; Medicaid’s impact on physical health remains inconclusive. Objective clinical data collected on both groups of adults two years after the lottery show that, relative to being uninsured, having Medicaid led to a 30% reduction in the rate of positive screens for depression. Gains in physical health were more limited: while Medicaid did increase the detection of diabetes and use of diabetes medication, it did not have a statistically significant effect on diabetes control, or on control of high blood pressure or high cholesterol. The researchers note that their study lacked sufficient statistical power to detect changes, and many of their point estimates are, in fact, within the range of clinically meaningful changes that would be expected if Medicaid were effective. The authors also identify multiple factors that may mitigate the impact of coverage on clinical outcomes, including unmeasured barriers to access, missed diagnoses, inappropriate medication, patient noncompliance, and ineffectiveness of treatments.

- Medicaid virtually eliminated catastrophic medical expenses. Catastrophic out-of-pocket spending (defined as costs exceeding 30% of income) was nearly eliminated among the adults who gained Medicaid coverage. Also, the likelihood of having medical debt was reduced by more than 20%, and having Medicaid had a significant impact on all self-reported measures of financial strain due to health care costs, including borrowing money or skipping other bills to pay medical bills and being refused treatment due to medical bills in the past six months.

Analyses that examine how Medicaid beneficiaries with serious chronic illnesses, such as diabetes, fare are of particular interest because of the prevalence of these conditions in the Medicaid population and the consequences if care is lacking. A recent series of studies focused specifically on low-income nonelderly adults with major chronic diseases shows statistically significant and clinically important differences between Medicaid beneficiaries and the uninsured on important measures of access and care. For example, adults with diabetes who are covered by Medicaid are less likely than those who lack insurance to report delaying or being unable to get needed care. They also have more office visits, fill more prescriptions, and are more likely to receive the key elements of recommended diabetes care.15 The two related studies on other major chronic illnesses show similar results.16

Continuity in Medicaid coverage makes a difference. Research has shown that interruptions in Medicaid coverage can lead to greater emergency department use as well as significant increases in hospitalization for conditions that can be managed on an ambulatory basis.17 18 19 Studies examining the short-term impacts of loss of Medicaid coverage provide additional evidence of Medicaid’s impact. Studies in California and Oregon of low-income adults who lost their Medicaid coverage found significant declines in basic measures of access, such as having a USOC, unmet health care and medication needs, and likelihood of a recent primary care visit, as well as significant declines in health status.20 21 In focus groups conducted with adult Medicaid beneficiaries in Massachusetts following the state’s elimination of adult dental benefits, nearly all the participants reported serious oral health problems that, for many, resulted in chronic and serious pain.22

Beyond showing improved access to care and use of recommended care for Medicaid beneficiaries relative to the uninsured, research also provides evidence that broader eligibility for Medicaid at the state level is associated with significant reductions in both child mortality23 and adult mortality.24 A study examining the relationship between broader state Medicaid coverage of adults and access to physician and preventive services found that higher levels of Medicaid coverage were associated with substantially improved access to care for all low-income adults in the state, and also that access gaps between low- and high-income adults were substantially larger in states with limited Medicaid coverage than in states with broader coverage.25

Finding #2: Medicaid beneficiaries and the privately insured have comparable access to preventive and primary care.

Given the benefits that cascade as health insurance lowers financial barriers and opens the door to the health care system, and, in contrast, the downstream deficits in care that the uninsured experience, measures of access to preventive and primary care, like having a USOC, receipt of a well-child visit, and cancer screening rates, can be seen not just as process measures or ends for their own sake, but as the anchors of high-quality care. Accordingly, how Medicaid beneficiaries do on these basic access measures is an important indicator of the quality of care in Medicaid. Many studies have used the experience of privately insured individuals as a benchmark for gauging Medicaid’s performance.

Children with Medicaid and privately insured children compare quite closely in their access to and use of preventive and primary care. Nationally, more than 95% of both groups of children have a USOC, and the very small percentage who report delaying or going without needed care due to cost in the past year is the same between the two groups, which is notable considering the lower income and greater health care needs of children covered by Medicaid.26 The most recent annual HHS report on the quality of care for children in Medicaid and CHIP concluded that children are similarly likely to have had a primary care visit in the past year whether they are publicly or privately insured.27 Younger children with public coverage appear to lag behind privately insured children on well-child visit rates and immunization rates, but adolescents with Medicaid or CHIP may fare as well as or better than adolescents with private coverage.

A recent report prepared for the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) reached similar findings when comparisons between publicly and privately insured children were adjusted for health, demographic, and socioeconomic differences between the two groups.28 It also found that children with public coverage are as likely as privately insured children to have had a specialist visit in the past year. At the same time, the report identified important measures of access on which Medicaid children fare slightly worse than those with private insurance. For example, they are less likely to have a USOC with night or weekend hours and are more likely to delay care for this reason. They are also more likely to lack transportation to the doctor’s office or clinic.

A companion study for MACPAC on adults enrolled Medicaid found that, when health, demographic, and socioeconomic differences were controlled for, Medicaid adults did as well as or better than privately insured adults on key measures, including USOC and receipt in the past year of a routine check-up, a general doctor visit, a specialist visit, a mammogram, and flu vaccination.29 The shares of Medicaid and privately insured adults reporting any unmet needs due to costs were comparable, but Medicaid adults were significantly less likely to report unmet needs for medical care, prescription drugs, and mental health care, compared with privately insured adults. These results are largely consistent with findings from other studies comparing Medicaid and privately insured adults’ access and utilization.30 31 32 A review of the literature on Medicaid’s impact on birth outcomes concluded that, when known risk factors for preterm birth and low birth weight are controlled for, birth outcomes are not different between women with Medicaid and privately insured women.33 Medicaid also provides greater financial protection than private health insurance.34,35 Research estimating how Medicaid beneficiaries would fare if they had private insurance instead projects that their out-of-pocket spending would increase more than three-fold on average, and that out-of-pocket burden would be heaviest for the subgroup of individuals with health limitations.36

Finding #3: Specialists are less willing to accept Medicaid patients than privately insured patients. However, studies comparing access to specialist care between Medicaid and private insurance have produced mixed findings – likely a reflection of the difficulty of adjusting for all the factors that may influence access.

As distinct from access to primary care, access to specialty care has emerged in some research as a weakness in Medicaid relative to private insurance. A review of the literature on children’s access to specialty care found that Medicaid children appear less likely than privately insured children to receive specialist care for various conditions and more likely to have trouble finding a physician willing to accept their insurance.37 Data included in the HHS report on Medicaid and CHIP children mentioned earlier show that fewer than half of parents with children enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP said it was always easy to get an appointment with a specialist, and the report cites access to specialty care as an area of particular concern. Consistent with those results, “secret shopper” and other studies have found specialist physicians and clinics far more likely to deny appointments to Medicaid and CHIP children than to privately insured children, and much longer wait times for appointments for publicly insured children.38 39 At the same time, the report for MACPAC, also mentioned earlier, found that observed gaps in access to specialty between publicly and privately insured children disappeared when demographic as well as health status differences between the two groups were controlled for.

In a nine-city audit study investigating adults’ access to specialist care, 64% of callers saying they were privately insured, but only 34% of those saying they had Medicaid, were able to secure an appointment for urgent follow-up care for three serious conditions, suggesting that Medicaid adults may lack adequate access to specialist care.40 However, the report for MACPAC on adults cited earlier determined that privately insured adults are no more or less likely than Medicaid adults to have a specialist visit. It showed that, when health status and demographic differences between the two groups are controlled for, the two groups are equally likely to have specialist visits overall, specialist visits excluding OB/GYN visits, and, for women, OB/GYN visits.41 This finding is at variance with the finding from another analysis, which projected that, if Medicaid adults were instead covered by private insurance, their use of specialists would be significantly higher.42

Finding #4: Studies examining the causes of higher emergency department (ED) use by Medicaid beneficiaries compared to the privately insured indicate that most of the difference is due to higher rates of symptoms determined by ED triage staff to need urgent attention. Barriers to access to care are also a factor.

Compared with both privately insured people and the uninsured, Medicaid beneficiaries have much higher rates of ED use.43 However, a substantial body of research investigating this disparity more closely indicates that poorer health and access challenges in Medicaid both play important roles in explaining Medicaid’s higher ED visit rates.

A study issued about a year ago showed that only a small portion of Medicaid patients’ higher ED use was explained by visits for non-urgent symptoms. Most of the Medicaid-private difference was attributable to more ED visits by Medicaid patients for symptoms that were judged by ED triage staff to need urgent or semi-urgent evaluation. Compared to nonelderly privately insured people, nonelderly Medicaid patients had almost double the rate of ED visits both for symptoms needing evaluation within an hour and for those needing evaluation within one to two hours.44 Also, compared with the privately insured adults with ED visits, the Medicaid adults were more likely to have a secondary diagnosis of a mental disorder, and their visits were more likely to involve more than one major chronic condition and more likely to involve a disability.

Other research provides evidence that increased ED utilization is associated with barriers to timely primary care, and that more accessible after-hours care is associated with lower rates of ED visits.45 46 A study examining the reasons for ED visits by nonelderly adults points in this direction; the results show that, compared with the privately insured with ED visits, Medicaid adults with ED visits were much more likely to report that they had no other place to go and that their doctor’s office or clinic was not open.47 A study probing factors associated with specialists’ willingness to accept children with public health insurance identified referral through hospital EDs as a common mechanism by which primary care physicians secure this care for their Medicaid and CHIP patients.48 The results from a recently published qualitative study seeking to identify the reasons that people of low socioeconomic status prefer hospital care to ambulatory care indicate that patients, too, see increased access to specialty care as one important advantage of seeking care in a hospital setting. Medicaid patients reported that while the direct costs of an ED visit and a physician office visit were similar, the overall cost associated with an office visit was greater because of the additional time and expense required for specialty visits or tests recommended by the primary care provider. Transportation also emerged as an issue. Finally, many patients reported that when they called physicians’ offices, they were advised to go to the ED.49

Finding #5: New evidence is emerging about the quality of care provided to Medicaid beneficiaries.

Research investigating the quality of care received by Medicaid beneficiaries is limited, but two new analyses, one focused on health center care and the other on hospital care, indicate that the care received by people with Medicaid coverage tracks closely with benchmarks for high quality.

Health center care

Health centers are a key source of preventive and primary care for medically underserved communities and populations, including millions of Medicaid beneficiaries. The ACA funded a major expansion of the health center program to help meet the expected increased demand for care as both Medicaid and private coverage expand. Given the role of health centers in providing care to Medicaid patients, evidence on the quality of care they deliver is important to an assessment of the Medicaid program itself. A recent study examined how health center performance on a set of three quality measures – diabetes control, blood pressure control, and receipt of a Pap test within the past three years – compares to the performance of Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs), which also serve a low-income population.50 The study defined the standard for “high performance” as the 75th percentile of Medicaid MCO quality scores, and the standard for “lower performance” as the mean Medicaid MCO quality score. Because all Medicaid MCO enrollees are insured but a large share of health center patients are uninsured, MCO performance is a demanding benchmark to use for health centers.

The study produced the following key findings:

- More than 1 in 10 health centers have consistently high performance relative to Medicaid MCOs. Of 1,200 health centers total, 130 outperformed three-quarters of Medicaid MCOs on all three measures of chronic and preventive care. Moreover, the average quality scores for these health centers exceeded the MCO high-performance benchmark by at least 10 percentage points on each measure. Many additional health centers were high-performing on individual measures, although not on all three – 80% met or exceeded the MCO high-performance standard for diabetes control, and over half did so for blood pressure control. Fewer than 4% of health centers were lower-performing on all three measures. However, in 70% of all health centers, Pap test rates trailed the average Medicaid MCO score, highlighting an important gap in the quality of preventive care for women.

- The consistently high-performing health centers were concentrated in certain states, as were consistently lower-performing health centers. A majority of states had at least one consistently high-performing health center, but one-third of such high-performers were in California, New York, and Massachusetts, where just 18% of all health centers are located. Similarly, one-third of the consistently lower-performing health centers were concentrated in three states – Louisiana, Texas, and Florida – that account for just over 10% of all health centers.

- Health centers with consistently lower performance are distinguished by extremely high uninsured and homeless rates. In the health centers that lagged behind average Medicaid MCO performance on all three quality measures, fully half the patients were uninsured, and well over one-third were homeless. The lower performance of these health centers probably says more about the profile of their patients and the limited resources available to health centers with high proportions of uninsured patients with complex health needs than about the quality of care provided to them. The higher rates of both private and Medicare coverage observed in the consistently high-performing health centers suggest that broader coverage as the ACA is implemented could help usher improvements in health center quality.

Hospital care

A team of Harvard researchers conducted a study to compare the quality of hospital care received by nonelderly adults covered by Medicaid and by private insurance, respectively, for three major conditions: heart attack, congestive heart failure, and pneumonia.51 Because the recommended processes of care for all these conditions are supported by strong scientific evidence, the researchers used “perfect care” – the receipt by an individual of all indicated processes of care – to gauge the quality of hospital care. Perfect-care scores for Medicaid patients and private-pay patients were calculated by aggregating the individual-level data by payer, both nationally and for each state.

The study found that:

- Medicaid and privately insured patients receive hospital care of very similar quality. The study found statistically significant but small differences at the national level between the shares of Medicaid and privately insured adults who received perfect care. Perfect-care scores were higher for privately insured patients, but the differences were between 1% and 3%. State-level differences in hospital quality between Medicaid and private-pay patients were also small – less than 3 percentage points on average. The largest Medicaid-private difference in a state was 14 percentage points for heart attack care, but fewer than 10 states had differences larger than 5 percentage points for any of the three conditions.

- State variation in the quality of hospital care Medicaid patients receive likely reflects geographic variation in how hospital care is delivered rather than state Medicaid policies. Notably, the researchers found significant variation in the quality of hospital care from state to state. However, quality tended to be higher for Medicaid patients where it was also higher for the privately insured, and lower for Medicaid patients where it was lower for the privately insured. The strong correlation in quality between Medicaid and privately insured patients suggests that the factors driving the quality of hospital care for Medicaid patients have more to do with how hospital care is delivered geographically, by state, than with factors related to state Medicaid policies.

Conclusion

In its totality, the research on Medicaid shows that the Medicaid program, while not perfect, is highly effective. A large body of studies over several decades provides consistent, strong evidence that Medicaid coverage lowers financial barriers to access for low-income uninsured people and increases their likelihood of having a usual source of care, translating into increased use of preventive, primary, and other care, and improvement in some measures of health. Furthermore, despite the poorer health and the socioeconomic disadvantages of the low-income population it serves, Medicaid has been shown to meet demanding benchmarks on important measures of access, utilization, and quality of care. This evidence provides a solid empirical foundation for the ACA expansion of Medicaid eligibility to millions of currently uninsured adults, and individuals and communities affected by the Medicaid expansion can be expected to benefit significantly. At the same time, the Medicaid program cannot overcome health care system-wide problems, like gaps in the supply and distribution of the health care workforce, or lack of access to transportation in low-income communities. Nor can Medicaid be expected to tackle many other barriers and issues that disproportionately affect low-income individuals and communities. These challenges require an additional set of policy responses beyond Medicaid’s ambit.

Still, Medicaid can be further strengthened by addressing recognized shortcomings in the current program. Securing adequate provider participation in Medicaid remains a key challenge. Improving continuity in Medicaid coverage is necessary to ensure that beneficiaries are able to obtain timely care and uninterrupted management of their chronic illnesses and disabilities. Rigorous oversight of the risk-based managed care arrangements in which more and more Medicaid beneficiaries receive their care is needed, especially as states expand managed care to people with more complex needs. New models of more coordinated and integrated care, and payment approaches that support them, are also needed. States are moving forward on all these fronts, often leading the way, and increased resources and flexibilities provided by the ACA continue to accelerate their progress. With stable and adequate federal and state investment in Medicaid, and state actions that leverage the purchasing power of the program to drive higher quality, Medicaid’s demonstrated potential to improve access and care for low-income people can be optimized.

Endnotes

Introduction

Gottlieb S, “Medicaid is Worse than No Coverage at All,” Wall Street Journal online, March 10, 2011. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704758904576188280858303612.html

The Path to Prosperity: A Responsible Balanced Budget. Fiscal Year 2014 Budget Resolution, House Budget Committee, March 2013. http://budget.house.gov/fy2014/

Senator Ted Cruz, PolitiFact.com, reported in Tampa Bay Times, April 1, 2013.

Dayaratna K, “Studies Show: Medicaid Patients Have Worse Access and Outcomes than the Privately Insured,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 2740, November 9, 2012.

Roy A, “Why Medicaid is a Humanitarian Catastrophe,” Forbes, March 2, 2011. http://www.forbes.com/sites/aroy/2011/03/02/why-medicaid-is-a-humanitarian-catastrophe/

Representative Bill Cassidy, C-Span interview, February 8, 2011. Accessed April 29, 2013 at http://thinkprogress.org/politics/2011/02/08/142979/cassidy-medicaid/

Care without Coverage: Too Little, Too Late, Committee on the Consequences of Uninsurance, Board on Health Care Services, Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press, 2002. (Page 6)

Issue Brief

Coverage Matters: Insurance and Health Care, Committee on the Consequences of Uninsurance, Board on Health Care Services, Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press, 2001. (Page 28)

Aday L and R Andersen, “A Framework for the Study of Access to Medical Care,” Health Services Research 9(3), Fall 1974.

Dubay L and G Kenney, “Health Care Access and Use among Low-Income Children: Who Fares Best?” Health Affairs 20(1), 2001.

Howell E and G Kenney, “The Impact of the Medicaid/CHIP Expansions on Children: A Synthesis of the Evidence,” Medical Care Research and Review 69(4), August 2012.

Selden T and J Hudson, “Access to Care and Utilization Among Children: Estimating the Effects of Public and Private Coverage,” Medical Care 44(5), 2006.

Kenney G and C Coyer, National Findings on Access to Health Care and Service Use for Children Enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP, MACPAC Contractor Report No. 1, March 2012.

Howell E, “The Impact of the Medicaid Expansions for Pregnant Women: A Synthesis of the Evidence,” Medical Care Research and Review 58(1), March 2001.

Long S et al., “How Well Does Medicaid Work in Improving Access to Care?” Health Services Research 40(1), February 2005.

Long S et al., National Findings on Access to Health Care and Service Use for Non-elderly Adults Enrolled in Medicaid. MACPAC Contractor Report No. 2, June 2012.

Coughlin T et al., “What Difference Does Medicaid Make? Assessing Cost Effectiveness, Access, and Financial Protection under Medicaid for Low-Income Adults,” Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, May 2013.

DeLeire T et al., “Wisconsin Experience Indicates that Expanding Public Insurance to Low-Income Childless Adults has Health Care Impacts,” Health Affairs 32(6), June 2013.

Baicker K and A Finkelstein, “The Effects of Medicaid Coverage – Learning from the Oregon Experiment,” The New England Journal of Medicine 365(8), August 25, 2011. (Also see Finkelstein et al., The Oregon Health Insurance Experiment: Evidence from the First Year, NBER Working Paper 17190, 2011. http://www.nber.org/papers/w17190)

Baicker K et al., “The Oregon Experiment – Effects of Medicaid on Clinical Outcomes,” The New England Journal of Medicine 368(18), May 2, 2013.

Kronick R and A Bindman, “Protecting Finances and Improving Access to Care in Medicaid,” The New England Journal of Medicine 368(18), May 2, 2013.

Garfield R and A Damico, “Medicaid Expansion under Health Reform May Increase Service Use and Improve Access for Low-Income Adults with Diabetes,” Health Affairs 31(1), January 2012.

The Role of Medicaid for Adults with Chronic Illnesses, Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, November 2012.

Ku L et al., Improving Medicaid’s Continuity of Coverage and Quality of Care, The George Washington University Department of Health Policy, July 2009.

Kasper J et al., “Gaining and Losing Health Insurance: Strengthening the Evidence for Effects on Access to Care and Health Outcomes,” Medical Care Research and Review 57(3), September 2000.

Cassedy A et al., “The Impact of Insurance Instability on Children's Access, Utilization, and Satisfaction with Health Care,” Ambulatory Pediatrics 8(5), September-October 2008.

Carlson M et al., “Short-Term Impacts of Coverage Loss in a Medicaid Population: Early Results from a Prospective Cohort Study of the Oregon Health Plan,” Annals of Family Medicine 4(5), September/October 2006.

Lurie N et al., “Termination from Medicaid: Does it Affect Health?” The New England Journal of Medicine 311(7), August 16, 1984.

Eliminating Adult Dental Coverage in Medicaid: An Analysis of the Massachusetts Experience, Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, August 2005.

Currie J and J Gruber, “Health Insurance Eligibility, Utilization of Medical Care, and Child Mortality,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 111(2), 1996.

Sommers B et al., “Mortality and Access to Care among Adults after State Medicaid Expansions,” The New England Journal of Medicine 367(11), July 25, 2012.

Weissman J et al., “State Medicaid Coverage and Access to Care for Low-Income Adults,” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 19(1), February 2008.

Health, United States, 2012, National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, May 2013.

2012 Annual Report on the Quality of Care for Children in Medicaid and CHIP, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, December 2012.

Kenney and Coyer, March 2012, Op. cit.

Long et al., June 2012, Op. cit.

Long et al., February 2005, Op.cit.

Coughlin T et al., “Assessing Access to Care under Medicaid: Evidence for the Nation and Thirteen States,” Health Affairs 24(4), July/August 2005.

Coughlin et al., May 2013, Op.cit.

Anum E et al., “Medicaid and Preterm Birth and Low Birth Weight: The Last Two Decades,” Journal of Women’s Health 19(3), 2010.

Kogan M et al., “State Variation in Underinsurance among Children with Special Health Care Needs in the United States,” Pediatrics 125(4), April 2010.

Magge H et al., “Prevalence and Predictors of Underinsurance aong Low-Income Adults,” Journal of General Internal Medicine, February 2013.

Coughlin et al., May 2013, Op.cit.

Skinner A and M Mayer, “Effects of Insurance Status on Children’s Access to Specialty Care: A Systematic Review of the Literature,” BMC Health Services Research 7(194), 2007.

Bisgaier J and K Rhodes, “Auditing Access to Specialty Care for Children with Public Insurance,” The New England Journal of Medicine 364(24), June 16, 2011.

Medicaid and CHIP: Most Physicians Serve Covered Children but Have Difficulty Referring them for Specialty Care, Government Accountability Office, June 2011.

Asplin B et al., “Insurance Status and Access to Urgent Ambulatory Care Follow-up Appointments,” Journal of the American Medical Association 294(10), September 2005.

Long et al., June 2012, Op.cit.

Coughlin et al., May 2013, Op. cit.

Garcia T et al., “Emergency Department Visitors and Visits: Who Used the Emergency Room in 2007?” NCHS Data Brief No. 38, May 2010.

Sommers A et al., “Dispelling Myths about Emergency Department Use: Majority of Medicaid Visits are for Urgent or More Serious Symptoms,” HSC Research Brief No. 23, July 2012.

Cheung P et al., “Changes in Barriers to Primary Care and Emergency Department Utilization,” Archives of Internal Medicine 171(15), August 2011.

O’Malley A, “After-Hours Access to Primary Care Practices Linked with Lower Emergency Department Use and Less Unmet Medical Need,” Health Affairs 32(7), December 2012.

Gindi R et al., Emergency Room Use among Adults Aged 18-64: Early Release of Estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, January–June 2011, National Center for Health Statistics, May 2012.

Rhodes K et al., “’Patients Who Can’t Get an Appointment Go to the ER’: Access to Specialty Care for Publicly Insured Children,” Annals of Emergency Medicine 61(4), April 2013.

Kangovi S et al., “Understanding Why Patients of Low Socioeconomic Status Prefer Hospitals over Ambulatory Care,” Health Affairs 32(7), July 2013.

Shin P et al., Quality of Care in Community Health Centers and Factors Associated with Performance, Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, June 2013.

Weissman J et al., “The Quality of Hospital Care for Medicaid and Private Pay Patients,” Medical Care 51(5), May 2013.