Tennessee & Other Medicaid 1115 Waiver Activity: Implications for the Biden Administration

Section 1115 waiver activity has been a key area of interest in the final weeks of the Trump Administration. Section 1115 authority allows the HHS Secretary to waive certain provisions of federal law in state Medicaid programs to test policies that are likely to promote program objectives. These waivers generally reflect administration priorities, although the Secretary’s discretion is not unlimited. The incoming Biden Administration could rescind existing waiver guidance (such as guidance related to work requirements and capped financing) and/or issue new guidance. It could also review provisions in currently approved waivers and renewal requests and move to withdraw or not renew waivers that do not promote program objectives. Although CMS generally reserves the right to withdraw approved waiver and/or expenditure authorities at any time, precedent for withdrawing approved waivers is limited.

In its final days, the Trump Administration has approved controversial waivers that had been pending (most recently for Tennessee), extended other waivers more than a year before expiration, and took steps to try to prolong the process for withdrawing or amending approved waivers. This issue brief takes a closer look at this recent activity to understand implications for the Biden Administration.

Tennessee Approval

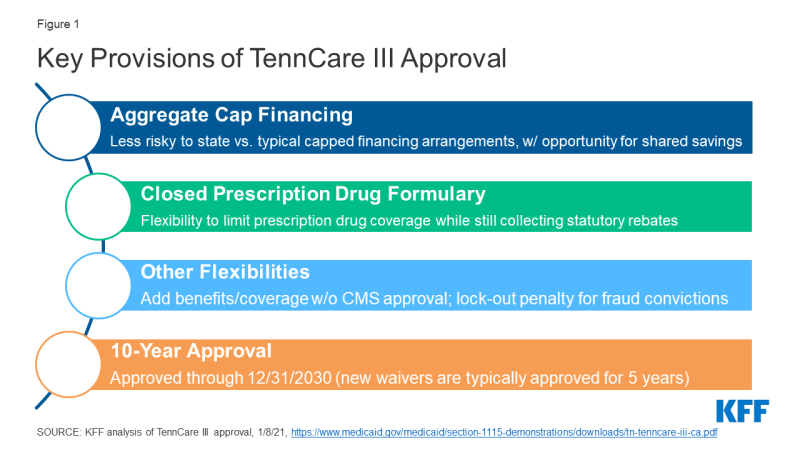

On January 8, 2021, CMS approved a waiver request from Tennessee that would transition nearly all of the state’s Medicaid program currently covered by its long-standing TennCare II waiver into a new TennCare III program. This waiver includes most TennCare enrollees, including children, parents, and pregnant women as well as many seniors and people with disabilities. This complex approval is particularly significant nationally due to provisions related to financing, drug coverage, and the duration of the waiver (Figure 1). These factors make Tennessee’s waiver a prime candidate for review by the Biden Administration.

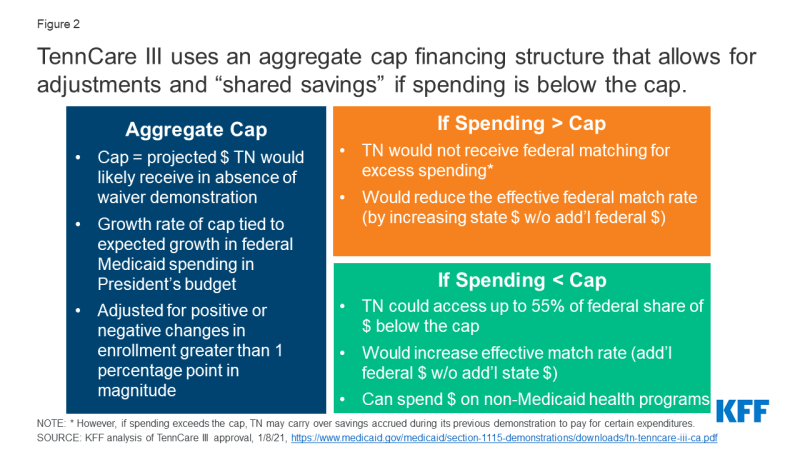

Financing: The TennCare III waiver sets an aggregate cap on federal spending and provides an opportunity for the state to keep a portion of any federal savings (Figure 2). Both of these features differ from the way Medicaid financing works under current law where costs and savings are shared by the states and the federal government due to the formula that guarantees federal matching dollars at a rate set in statute without a pre-set limit. While Section 1115 waivers must be budget neutral to the federal government, that budget neutrality is typically determined on a per enrollee basis rather than an aggregate basis. In the past, capped demonstrations have been approved in Rhode Island, Vermont, and Virginia (for a limited population), but they are no longer in place in these states. CMS is explicit that its approval of Tennessee’s waiver is not a part of the Trump Administration’s Healthy Adult Opportunity (HAO) initiative, which allows for capped financing. The match rate is an area of Medicaid that may not be changed under Section 1115 waiver authority. Key financing elements of TennCare III include:

- Setting the Cap. The aggregate cap would be adjusted each year to reflect the expected growth in federal Medicaid spending in the President’s budget and adjusted for positive or negative changes in enrollment that are greater than one percentage point in magnitude.

- Spending Above the Cap. Typically, capped financing would pose fiscal risks to states and could lower a state’s effective match rate because any state spending above the cap would not receive federal matching funds, as is the case with capped financing for Puerto Rico and the other Territories. However, adjustments to Tennessee’s cap tied to the growth rate for Medicaid in the President’s budget (which has historically been higher than inflation and higher than the Tennessee’s historic growth) and to increased enrollment mitigate the risk of this capped financing model to Tennessee. If Tennessee’s expenditures do exceed the cap, the state may carry over savings accrued during the final five years of TennCare II to pay for certain expenditures. While Tennessee must submit an amendment to reduce the level of benefits or covered populations below what was in place at the end of 2020, the TennCare III approval does not prohibit such changes.

- Spending Below the Cap. If expenditures are below the cap in a given demonstration year, Tennessee may access up to 55% of the federal share of savings to reinvest in state health programs (including those not eligible for Medicaid funding) if the state meets certain quality metrics (to be determined by Tennessee and CMS in the coming months), in addition to retaining 100% of the savings the state would normally get under Medicaid matching formula. Under this provision, Tennessee could see a higher effective match rate than statutory levels since this opportunity for shared savings allows the state to receive additional federal Medicaid dollars without additional state spending. Prior CMS guidance related to the use of federal Medicaid funds for non-Medicaid state programs has been mixed. Guidance from 2017 noted that CMS would no longer allow federal matching funds for designated state health programs (DSHP); however, in its approval of TennCare III CMS explained that it would allow for federal funds for non-Medicaid state health programs in line with policy principles established in its Health Adult Opportunity (HAO) guidance.

Closed Formulary: Under federal rules, in exchange for significant rebates on prescription drugs, state Medicaid programs must cover nearly all drugs approved by the FDA, essentially requiring an “open formulary” (unlike private insurers, who can enter into negotiations with manufacturers about whether or not to include drugs on the insurers’ formularies). The TennCare III approval would allow Tennessee to instead cover the greater of either one drug per therapeutic class or the same number of drugs per class as a selected Essential Health Benefits benchmark plan in the Affordable Care Act exchange, with an exceptions process for coverage of non-formulary drugs. Tennessee could still collect statutory rebates for covered drugs. CMS previously rejected a similar proposal in Massachusetts.

10-Year Approval: In November 2017 guidance, CMS indicated it would consider approving “routine, successful, non-complex” Section 1115 extension requests for up to 10 years. Since then, CMS has approved 10-year waiver extensions for three non-family planning demonstrations (WI, ME, and IN). CMS approved TennCare III for 10 years even though it does not appear to meet the conditions in the 2017 guidance: it was approved as a new waiver (not an extension), received 6,186 comments (of which “the vast majority” opposed the waiver), and contains complex financing and provisions.

Other Key Waiver Issues to Watch

Other recent activity under the Trump Administration may hamper the Biden Administration’s efforts to review certain waivers.

Expedited and Early Approval of Waivers. On January 15, 2021 CMS approved a ten-year extension for the Texas Healthcare Transformation and Quality Improvement Program (THTQIP) waiver following a “fast track” extension process which allowed the state to waive public notice and comment requirements (citing the immediacy of the COVID-19 public health emergency). The THTQIP waiver had been set to expire on September 30, 2022. On the same day, CMS renewed Florida’s Managed Medical Assistance waiver (which had been set to expire in June 2022) through June 2030. These renewals include provisions that the Biden Administration may review, including uncompensated care pools which provide funding for people who could be covered through the Medicaid expansion. Early approvals of these requests under the Trump Administration may make it more difficult for the Biden Administration to modify or withdraw these provisions subsequently.

Process to Withdraw Waiver Authorities. Outgoing CMS Administrator Seema Verma has encouraged states to sign a “letter of agreement” that specifies that any future CMS determination suspending, terminating, or withdrawing a waiver must have an effective date no sooner than nine months after the initial determination. The letter also specifies timelines for hearings and a briefing schedule for states to challenge these determinations. These agreements could make it more difficult for the Biden Administration to amend or withdraw waivers that it determines to be inconsistent with Medicaid program objectives, depending upon how they are construed. Congressional Democrats have noted that these “letters of agreement” conflict with existing regulations that require CMS to establish such a process as part of each waiver’s terms and conditions and requested that CMS rescind them immediately.

Pending Litigation. The Supreme Court is reviewing appeals court decisions setting aside work requirement waivers in Arkansas and New Hampshire, with the opening briefs filed by the Trump Administration and states on January 19, 2021. Although the Biden Administration is likely to rescind guidance related to Medicaid work requirements and could move to withdraw other currently approved work requirement waivers, a Supreme Court ruling in favor of the HHS Secretary’s authority to approve work requirements could still leave these waivers open to future administrations.