Supplemental Security Income for People with Disabilities: Implications for Medicaid

Key Takeaways

The federal Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program provides a cash payment to serve as a minimum level of income for people who have low incomes and limited assets and are elderly or meet the Social Security Administration’s (SSA) strict rules that define disability. The maximum federal SSI benefit is less than the federal poverty level (FPL), $794 per month or about 74% FPL for an individual, in 2021. As a result of the SSA’s strict disability determination rules, not all people with disabilities qualify for SSI. States generally must provide Medicaid to people who receive SSI. This issue brief describes key characteristics of SSI enrollees, explains the SSI eligibility criteria and eligibility determination process, and considers the implications of changes in the SSI program for Medicaid, including the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting economic downturn and proposals supported by President Biden that Congress might consider. Key findings include the following:

- Working people with disabilities experience disproportionate job loss during economic downturns compared to workers without disabilities, and SSI applications generally increase when the unemployment rate increases.

- The COVID-19 pandemic has presented additional challenges not present during other economic downturns, such as the closure of SSA offices due to social distancing measures.

- People in households where someone experienced a job or income loss were more than three times as likely to have applied or attempted to apply for SSI during the pandemic, or plan to apply in the next 12 months, compared to those in households without job or income loss.

- Because SSI eligibility generally is a pathway for Medicaid eligibility, changes that affect the ability of people with disabilities to obtain or retain SSI also can affect the ability of people with disabilities to access Medicaid.

SSA expects disability claims (including SSI and SSDI) to increase by nearly 300,000 in the second half of FY 2021, and over 700,000 in FY 2022, compared to FY 2020. SSA received fewer applications than expected in FY 2020, due to office closures and other disruptions due to the pandemic. Additionally, the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) Medicaid expansion was not available during prior economic downturns, so the extent to which people might forgo an SSI application (as a means to access Medicaid) because they are eligible for Medicaid through the ACA expansion (in states that have chosen to expand) remains to be seen. Finally, the extent of chronic disabling illness experienced by people with “long COVID” is not yet fully understood but could result in a new population seeking SSI due to their inability to work.

Introduction

Congress created the federal SSI program in 1972, as a safety net program of “last resort,” providing a cash payment to serve as a minimum level of income for poor people who are elderly or disabled and meet strict federal rules.1 To be eligible for SSI, beneficiaries must have low incomes, limited assets, and either be age 65 or older or have an impaired ability to work at a substantial gainful level as a result of significant disability.2 SSI is a separate program from Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI), which provides cash payments to people who previously worked but are no longer able to work due to disability.3 Notably, states generally must provide Medicaid to people who receive SSI.4 By contrast, SSDI eligibility generally triggers Medicare eligibility after a 24-month waiting period; unlike SSDI and Medicare eligibility, there is no waiting period before an SSI enrollee is eligible for Medicaid.5 Box 1 explains other key differences between SSI and SSDI.

The maximum federal SSI benefit is less than the federal poverty level (FPL), $794 per month or about 74% FPL for an individual, in 2021.6 A couple in which both spouses are eligible for SSI receives a joint maximum federal payment of $1,191 per month, which is one and one-half times the individual benefit amount.7 Because SSI payments are reduced to account for any earned or unearned income as well as support that is deemed or received in-kind from other people, the average federal SSI payment is about $586 per month, as of April 2021.8 States have the option to make supplemental payments to SSI enrollees, which can vary based on income, living arrangement, and other factors.9 This issue brief describes key characteristics of SSI enrollees, explains the SSI eligibility criteria and eligibility determination process (with additional detail contained in the Appendix), and considers the implications of changes in the SSI program for Medicaid, including the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting economic downturn as well as proposals supported by President Biden that Congress might consider.

Box 1: What is the Difference Between SSI and SSDI?

SSI is a federal program administered by the Social Security Administration (SSA) that ensures a minimum level of income for poor people who are elderly or disabled. To qualify, SSI enrollees must have low income, limited assets, and either be age 65 or older or have an impaired ability to work at a substantial gainful level according to strict federal rules.10 Unlike SSDI (described below), SSI is available to people regardless of their work history. The maximum SSI benefit is set by Congress.11

SSA also administers Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI), a separate program from SSI.12 Unlike SSI, there are no income or asset limits for SSDI eligibility. Instead, to qualify for SSDI, enrollees must have a sufficient work history (generally, 40 quarters) and meet the strict federal disability rules.13 SSA uses the same rules to determine disability for both the SSI and the SSDI programs.14 In addition, some people with a disability can qualify for SSDI based on a relative’s work history. For example, people whose disability began before age 22, known as “disabled adult children,” can qualify for SSDI based on the work history of their parent who is retired, deceased, or disabled.15

The amount of SSDI benefits is based on the person’s earnings history.16 It is possible to receive both SSDI and SSI if a person’s SSDI benefit amount is less than the maximum SSI payment. In those cases, the person also can qualify for SSI to cover the difference between their SSDI benefit amount and the maximum SSI benefit.

Who receives SSI?

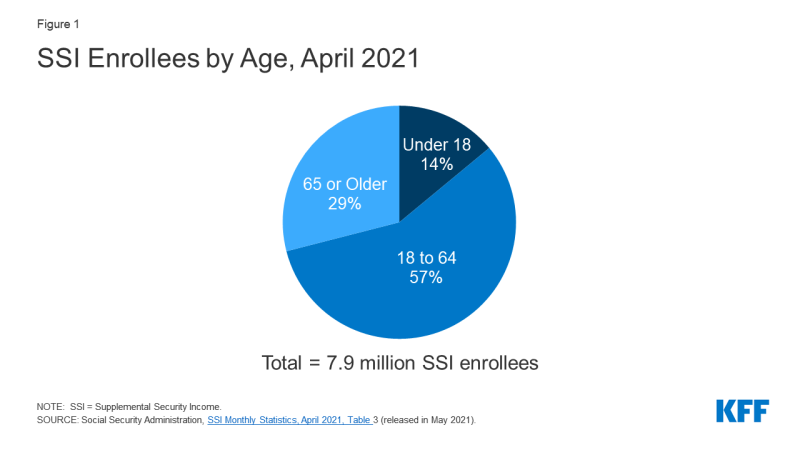

Nearly 8 million people receive SSI benefits as of April 2021 (Figure 1). The majority of SSI enrollees (57%) are nonelderly adults. Over one-quarter are seniors, and the remainder are children.

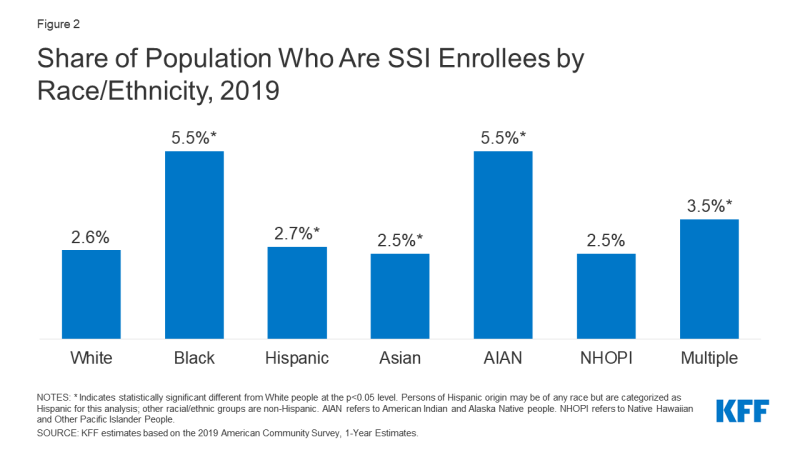

The rate of SSI receipt varies by racial/ethnic group (Figure 2). People who are Black or American Indian/Alaska Native are more than twice as likely to receive SSI compared to White people.

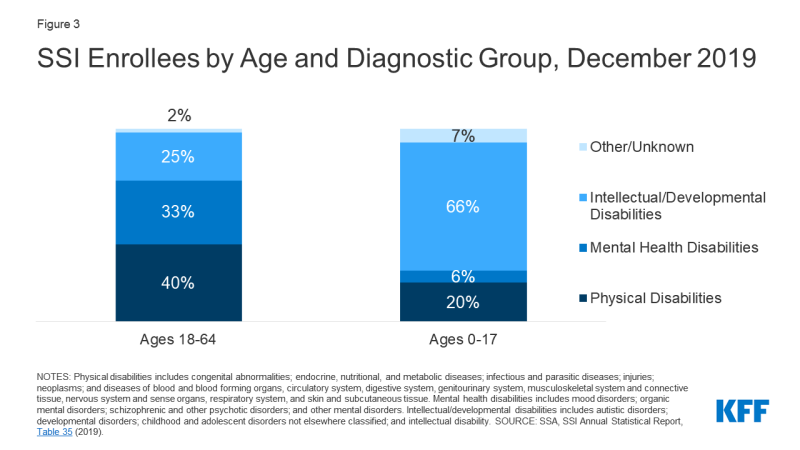

Grouped into broad categories, 40 percent of nonelderly adult SSI enrollees had a physical disability as of December 2019 (Figure 3). People age 65 and older are excluded as they can qualify for SSI based on their age rather than disability status. The most prevalent types of physical disabilities (using SSA’s terminology) were musculoskeletal disorders (generally involving impairment of one or both arms or legs, as well as soft tissue injuries), followed by neurological disorders (such as epilepsy, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), or muscular dystrophy) or loss of vision, speech or hearing; and circulatory disorders. One-third of nonelderly adult SSI enrollees qualified based on a mental health disability. The most prevalent types of mental health disabilities were schizophrenic and other psychotic disorders, followed by mood disorders (such as depression or bipolar disorder). One-quarter of nonelderly adult SSI enrollees have an intellectual or developmental disability (I/DD). Within this category, the most prevalent type was intellectual disability, followed by autism.

In contrast to adult SSI enrollees, two-thirds of child SSI enrollees have an I/DD as of December 2019 (Figure 3). The most prevalent type of disability within the broad I/DD category was developmental disability. One in five child SSI enrollees have a physical disability. The most prevalent types of physical disabilities among child SSI enrollees were neurological disorders or loss of vision, speech or hearing, followed by congenital disorders. Less than 10 percent of child SSI enrollees have a mental health disability. Within this category, the most prevalent disability types were mood disorders, followed by organic mental disorders.

How does a person qualify for SSI?

In addition to meeting the disability criteria (described below), an SSI enrollee must meet several non-medical criteria, including having a low income. SSA has complex rules for determining financial eligibility. In general, income is anything received in cash, earned or unearned, that can be used to meet a person’s need for food or shelter.17 Income is countable except for some limited amounts that are disregarded.18 Income also includes “in kind” support, such as any food or shelter provided or paid by another person. In kind support generally is valued at (and therefore reduces SSI payments by) one-third of the maximum federal benefit amount.19 SSA also deems a portion of income from a person’s spouse or parent/step-parent (for child applicants) as countable income.20 To financially qualify for SSI, a person’s countable income cannot exceed the maximum federal benefit rate ($794/month for an individual in 2021), and the amount of SSI that a person actually receives is the maximum federal rate reduced by the amount of their countable income.21 These rules apply to SSI enrollees of all ages.

Other non-medical criteria to qualify for SSI include having limited assets and a qualifying citizenship or immigration status. SSI eligibility requires that a person’s countable assets not exceed $2,000 for an individual and $3,000 for a couple in which both spouses are eligible for SSI.22 As with income, SSA deems a portion of assets from a person’s spouse or parent as countable.23 Examples of assets that are excluded from the limit include the individual’s home, household effects, and one automobile.24 SSI eligibility also generally is limited to U.S. citizens.25

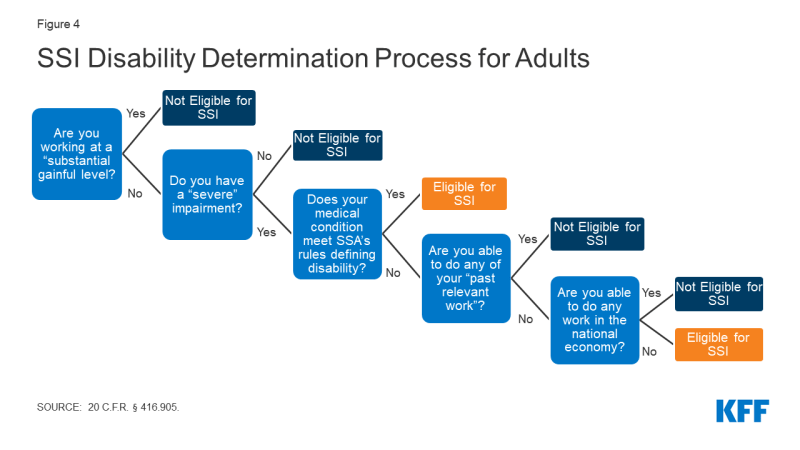

SSA uses a five-step process to determine whether a nonelderly adult qualifies as disabled for purposes of receiving SSI (Figure 4).26 By contrast, people age 65 and older can qualify for SSI based on their age. The first step in the disability determination process for nonelderly adults considers whether the person currently has earned income at or above the amount that SSA considers a “substantial gainful level.” The next question is whether the person has a “severe” impairment,” defined as a medically determinable impairment that lasts at least 12 months or results in death.27 The third step involves examining whether the person meets SSA’s strict rules that define whether the medical impairment meets the definition of disability. If a person does not meet SSA’s disability definition, the final two steps consider their ability to return to their past work or to do any work. SSA’s process to determine disability for purposes of SSI eligibility for children differs in some respects from the process used for adults to account for differences in functioning between the two populations.28 More detail is provided in the Appendix.

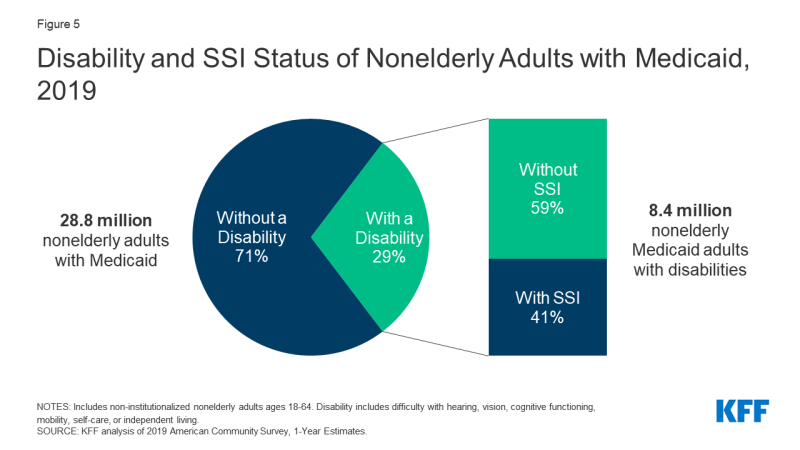

As a result of the strict SSA disability determination rules, not all people with disabilities qualify for SSI. For example, using one definition of functional disability, more than six in 10 nonelderly Medicaid adults who report a functional disability do not receive SSI (Figure 529). The definition of functional disability here includes people who report serious difficulty with hearing, vision, cognitive functioning (concentrating, remembering, or making decisions), mobility (walking or climbing stairs), self-care (dressing or bathing), or independent living (doing errands, such as visiting a doctor’s office or shopping, alone).30 Nonelderly adults with disabilities who do not receive SSI can qualify for Medicaid through other eligibility pathways including those based solely on their low income, such as the ACA’s Medicaid expansion or Section 1931 parents, or those based on disability, such as the state option to cover people with disabilities up to the federal poverty level or a home and community-based services waiver.31

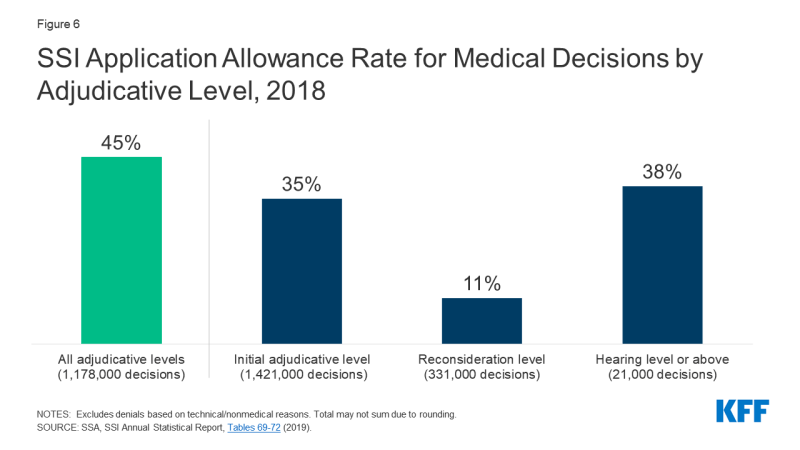

A notable share of initial decisions denying SSI eligibility are reversed on appeal (Figure 6). The overall “allowance rate,” awarding SSI benefits in cases involving medical determinations (excluding those denied for “technical” reasons such as such as income or assets) across all adjudicative levels in 2018, was 45 percent.32 However, the rate of SSI awards varies by adjudicative level. Thirty-five percent of applications involving medical determinations were approved at the initial application stage.33 Among cases involving medical determinations that were denied at the initial application and appealed, very few (11%) were awarded benefits at the first appeals level (reconsideration).34 However, nearly 40 percent of cases involving medical determinations that were denied at both the initial application and reconsideration levels and were appealed further ultimately had benefits awarded, at an administrative law judge (ALJ) hearing or higher appeals level.35 The appeals process can take a long time and can be difficult for individuals to navigate on their own without legal representation. For example, the average wait time between an ALJ hearing request (the second appeal level) and a hearing date ranged from five months to over 16 months, depending on the hearing office location, in March 2021.36

After the initial eligibility determination, SSI enrollees are subject to “continuing disability reviews.” The timeframes for these reviews are established based on whether and when SSA expects the person’s medical condition to improve. SSI eligibility also is reviewed for other reasons, such as a return to work, increased wages, or completion of vocational rehabilitation training.37 Additionally, child enrollees who turn 18 have their eligibility reviewed using the adult disability determination rules.38

How has the COVID-19 pandemic and associated economic downturn affected SSI and Medicaid?

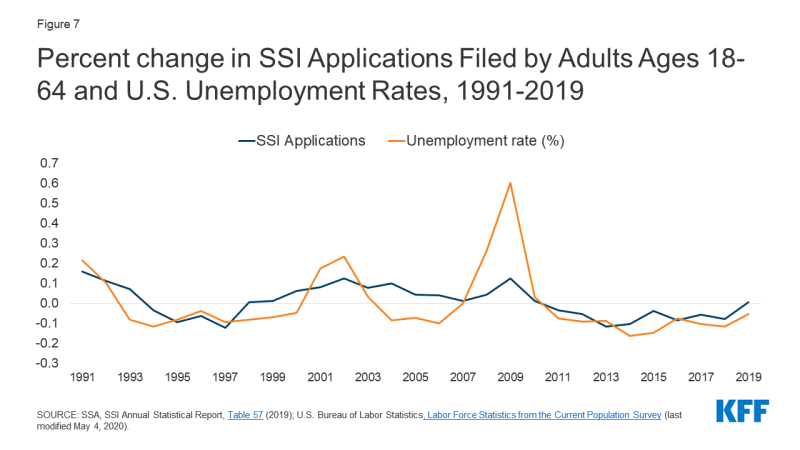

Working people with disabilities experience disproportionate job loss, compared to workers without disabilities, during economic downturns,39 and SSI applications generally increase when the unemployment rate increases (Figure 7). This trend held during the Great Recession and subsequent economic recovery.40 One exception to the general trend is the period from 2003 to 2007, when SSI applications continued to rise despite falling unemployment.41 Possible explanations for this anomaly include factors such as the lagged effect of federal welfare reform (passed in 1996) leading TANF enrollees to switch to SSI and “persistently high poverty rates.”42 The same study also found that the likelihood of applying for SSI significantly increases during extended periods of high unemployment.43

Figure 7: Percent change in SSI Applications Filed by Adults Ages 18-64 and U.S. Unemployment Rates, 1991-2019

SSA projects an increase in disability applications in the second half of FY 2021 and in FY 2022.44 Specifically, SSA expects to complete nearly 300,000 more claims in FY 2021, and over 700,000 more claims in FY 2022, compared FY 2020.45 While SSA received nearly 190,000 fewer disability applications than anticipated in FY 2020, the agency expects “many of these individuals to apply for benefits as we emerge from the pandemic” and notes that some people may have been unable to obtain the help they needed to apply earlier in the pandemic.46 (SSA does not separately discuss SSI vs. SSDI applications in these projections.) Additionally, the extent of chronic disabling illness experienced by people with “long COVID” is not yet fully understood but could result in a new population seeking SSI due to their inability to work.

The pandemic has presented additional challenges that have not been present during other economic downturns. For example, the need for social distancing measures has closed SSA offices to the public since mid-March 2020. In April 2021 testimony before the Senate Finance Committee, the SSA Deputy Commissioner for Operations acknowledged the importance of in-person services for many populations served by SSA, such as seniors, people with low incomes, those with limited English proficiency, those who are homeless, and those with mental illness, and described SSA’s outreach efforts to these groups.47 SSA explained that before the pandemic, most or all tasks could be completed at the first point of contact in the office, while collecting evidence and documentation by mail or phone has slowed the process down, often requiring multiple contacts.48 Additionally, SSA cited mail delays, people who no longer receive mail at their address of record because they were forced to move during the pandemic, and hesitancy in accepting phone calls due to phone scams as factors that have exacerbated challenges resulting from office closures.49 SSA also noted that “at least 30 percent of all disability applications require a consultative examination to determine disability,” and the pandemic has made it more difficult for people to schedule and access these appointments with medical providers and to obtain evidence from schools and social service agencies.50 SSA reported that these tasks are “taking almost twice as long now, up from 21 days before the pandemic to 37 days during the pandemic.”51 Consequently, SSA is facing a backlog of initial disability applications that “grew by approximately 115,000 cases” between September 2019 and April 2021.52

As of mid-March 2021, KFF analysis of Census survey data shows that 4.6 million people had applied or attempted to apply for SSI during the pandemic, or think they will apply in the next 12 months, with those in households that experienced job or income loss more likely to do so.53 People in households where someone experienced a job or income loss were more than three times as likely to have applied, attempted to apply, or plan to apply for SSI, compared to those in households without job or income loss.54 Among those who have applied, tried to apply, or plan to apply, one quarter said the pandemic led them to apply earlier than expected, while 15% said the pandemic led them not to apply or apply later than expected.55

SSI enrollment remained relatively stable in the early months of the pandemic but began to decrease as the pandemic continued.56 When the pandemic began, SSA “temporarily deferred” some work, such as continuing disability reviews and SSI redeterminations, “to protect beneficiaries’ income and healthcare during a critical time.”57 SSA “resumed processing adverse actions in September and October of 2020.”58 This likely has contributed to the decrease in the number of SSI enrollees from nearly 8.1 million in April 2020 to just under 7.9 million in April 2021.59 Historically, SSI enrollment increased annually from 2000 through 2013. Then, beginning in 2014, annual SSI enrollment has declined slightly each year. 2014 is the first year that the ACA’s Medicaid expansion went into effect, and the extent to which the availability of this new Medicaid pathway may have influenced SSI enrollment declines is unclear. The overall decrease in enrollment from April 2020 to April 2021 is consistent with the general recent trend of annual SSI enrollment declines since 2014.

Medicaid enrollment increased in every state during the COVID-19 pandemic.60 Medicaid enrollment grew by 11.8% (7.6 million enrollees) nationally from actual adjusted February to preliminary November 2020 data.61 While enrollment increased for both children and adults during this period, adult enrollment grew at a greater pace.62 This reflects changes in the economy (as more people lost income and jobs and became eligible for and enrolled in Medicaid) as well as provisions in the Families First Coronavirus Response Act that require states to ensure continuous coverage for current Medicaid enrollees through the end of the month in which the COVID-19 public health emergency ends, as a condition of receiving a temporary increase in the Medicaid federal matching rate.63

Implications for Medicaid

Because SSI eligibility generally is a pathway for Medicaid eligibility, changes that make it more difficult to obtain or retain SSI can affect the ability of people with disabilities to access Medicaid. For example, in January 2021, the Biden Administration withdrew a notice of proposed rule-making issued by the Trump Administration that would have increased the number and frequency of continuing disability reviews and was expected to result in some people losing SSI eligibility.64 Increasing the frequency of SSI continuing disability reviews could create administrative barriers that can result in eligible people losing not only SSI but also Medicaid.65 An increase in the number of people losing SSI also could increase state administrative costs because state Medicaid agencies must determine Medicaid eligibility on all other bases before terminating coverage if people lose eligibility through their current pathway.66

On the other hand, changes that seek to increase and stabilize access to SSI could have similar effects on the ability of people with disabilities to obtain and retain Medicaid coverage. For example, President Biden and a group of Congressional Democrats have proposed increasing the maximum SSI benefit to 100% FPL; eliminating the SSI “marriage penalty” (referring to the fact that two SSI enrollees who marry receive the couple rate, described above, which is less than twice the individual rate); eliminating rules that reduce SSI benefits by one-third based on “in-kind support and maintenance;” and raising the asset limits, which last increased in 1989.67 President Biden backed these policy changes during his campaign, and a group of Congressional Democrats supports including them in the American Family Plan.68

The availability of the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) Medicaid expansion as an alternative pathway to affordable health insurance coverage can affect decisions about whether to apply for SSI during the current economic downturn. The ACA expansion was not available during prior economic downturns, so the extent to which people might forgo an SSI application (as a means to access Medicaid) because they are eligible for Medicaid through the ACA expansion is not yet fully understood. Limited research indicates possible federal and state savings due to decreased SSI participation associated with the ACA Medicaid expansion.69 Although it is not often thought of in these terms, the ACA expansion provides a pathway to Medicaid eligibility for many people with disabilities, though without the limited cash benefits SSI provides and without the need to navigate SSI’s disability determination process. While it is true that disability status is not one of the eligibility criteria to qualify for the ACA expansion group, nonelderly adults with disabilities who do not receive SSI can qualify for Medicaid based solely on their income through the expansion group.70 Many people in the ACA expansion group were previously ineligible for Medicaid, and eligibility remains limited in the 12 states that have not adopted the Medicaid expansion to date, where eligibility limits for parents remain very low, and there is no eligibility pathway for childless adults, regardless of income (except in Wisconsin).71 Medicaid eligibility pathways based on disability other than SSI receipt, such as the pathway to cover seniors and people with disabilities up to 100% FPL, are offered at state option and therefore not universally available.72

Access to affordable health insurance, such as Medicaid, helps people with disabilities access services to meet daily self-care and independent living needs, such as bathing, dressing, and eating. Medicaid also supports working people with disabilities by covering the health and long-term care services they need to be able to work. For example, the optional Medicaid buy-in for working people with disabilities allows Medicaid eligibility to continue for people who lose SSI due to earned income, if losing Medicaid would “seriously inhibit [the person’s] ability to continue working” and earnings are insufficient to provide a “reasonable equivalent of benefits. . . which would be available” if not working.73 Together, SSI and Medicaid are key sources of support for low-income seniors, nonelderly adults, and children with disabilities.