Options to Support Medicaid Providers in Response to COVID-19

As with other payers, the coronavirus pandemic has resulted in financial strain for Medicaid providers. Some providers are dealing with both increased utilization and costs related to testing and treatment of COVID-19, while others are facing substantial losses in revenue as utilization has declined for non-urgent care. Medicaid providers include those that serve a high share of Medicaid enrollees and/or deliver services primarily financed by Medicaid, such as behavioral health or long-term care. These providers may face disproportionate risks to their continued financial viability as they may already have lower reimbursement levels relative to costs and lower operating margins. Within broad federal rules, states determine how Medicaid services are delivered and set reimbursement rates (or capitation payments for managed care).

In light of the pandemic, CMS has provided some guidance about options under current Medicaid rules that states can use to provide financial support for some providers. In addition, Congress has authorized $175 billion in new provider relief grants in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act and the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act to help bolster providers; however, the Administration’s plans to allocate those funds may not adequately address issues for providers that serve a disproportionate share of Medicaid enrollees. This brief provides an overview of how states currently reimburse providers and the challenges for Medicaid providers that have emerged from the pandemic and state budget issues. It presents new data on state actions to date to help bolster Medicaid providers dealing with the effects of COVID-19 and discusses support available for Medicaid providers from the federal provider relief fund.

What Challenges are Providers Facing Due to COVID-19?

Many Medicaid providers may be under fiscal strain as a result of the pandemic. Some providers are dealing with both increased utilization and costs related to testing and treatment of COVID-19, while others are facing substantial losses in revenue as utilization has declined for non-urgent care. For providers in states that rely heavily on managed care, states have made payments to the plans, but those funds may not be flowing to providers where utilization has decreased.

Medicaid providers may have been more fiscally vulnerable prior to the pandemic. Community health centers are a key source of primary care, and safety-net hospitals, including public hospitals and academic medical centers, provide a lot of emergency and inpatient hospital care for Medicaid enrollees. Safety-net hospitals and clinics as well as other providers that rely on Medicaid funding, including behavioral health providers, substance use disorder treatment providers, home and community-based service providers, children’s hospitals, pediatricians, and maternal health providers, may operate with lower operating margins and are vulnerable to fiscal stress from the pandemic. For example, recent data show that significant numbers of community health centers are closing, and federal fiscal relief from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act (CARES) and Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act may not be sufficient to address financial and workforce issues that have been exacerbated by the pandemic.

How Does Medicaid Reimburse Providers Now?

Within broad federal rules, states have considerable flexibility in how they deliver and pay for services for Medicaid enrollees. States have latitude to determine provider payments so long as the payments are consistent with efficiency, economy, quality and access and safeguard against unnecessary utilization. Within these broad guidelines, provider payments must be sufficient to ensure Medicaid beneficiaries with access to care that is equal to others in the same geographic area. Over the years, beneficiaries and providers used this legal requirement, known as the “equal access provision,” to ensure that states use Medicaid provider payment rate setting methodologies that provide equal access. In 2015, however, the Supreme Court ruled in Armstrong v. Exceptional Child that providers could not bring lawsuits to enforce the equal access provision in federal court. Following the case, HHS issued regulations requiring states to measure access in fee-for-service delivery systems. Under the Trump Administration, HHS has proposed to rescind the regulations that require states to document access to care and service payment rates and include input from Medicaid providers, beneficiaries, and other stakeholders about the impact on access to care when proposing to reduce or restructure payment rates. That proposal is still pending at CMS.

Under current law, states can pay certain types of fee-for-service providers up to what Medicare would have paid in aggregate across the type and class of provider. States often use these upper payment limit (UPL) arrangements to direct supplemental payments to certain Medicaid providers to offer additional financial support. The use of UPL arrangements was under intense scrutiny at CMS prior to the pandemic, and the future of some of these arrangements is in question depending on the fate of the proposed Medicaid Fiscal Accountability Rule (MFAR) that is pending at CMS. If finalized as proposed, that rule would limit states’ ability to use supplemental payments and restrict what funds states can use for their state share of Medicaid spending. MFAR could affect existing Medicaid financing arrangements in most states, and there were over 4,000 comments on the proposed rule. The Health and Economic Recovery Omnibus Emergency Solutions Act (HEROES Act) passed by the House on May 15, prohibits the Secretary from taking any action to finalize or implement the proposed rule through the end of the public health emergency; that bill has not been taken up by the Senate to date.

Payments to Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) must be actuarially sound. Actuarial soundness means that “the capitation rates are projected to provide for all reasonable, appropriate, and attainable costs that are required under the terms of the contract and for the operation of the managed care plan for the time period and the population covered under the terms of the contract.” Unlike fee-for-service, capitation provides upfront fixed payments to plans for expected utilization of covered services, administrative costs, and profit. States generally pay the plans a capitation payment, but then the plans determine how to pay the providers in their network. Information is limited regarding the rates paid by plans to providers in managed care.

Under current MCO rules, states are prohibited from directing how a managed care plan pays its providers except for certain payment methodologies that have been approved and reviewed by CMS. States may require MCOs to adopt minimum or maximum provider payment fee schedules or provide uniform dollar or percentage increases for network providers that provide a particular service under the contract, as approved by CMS. States also can seek CMS approval to require MCOs to implement value-based purchasing models for provider reimbursement (e.g., pay for performance, bundled payments) or participate in multi-payer or Medicaid-specific delivery system reform or performance improvement initiatives. State directed payments must be based on utilization and delivery of services covered under the managed care plan contract. The proposed MCO rule pending at CMS would make some changes to minimum fee schedule arrangements for directed payments. The 2016 final rule phases out state supplemental pass-through provider payments in the capitation rates paid to managed care plans because these payments are not tied to the provision of services covered under plan contracts and therefore conflict with the actuarial soundness requirement. Specifically, the 2016 rule phases out pass-through payments to hospitals from 2017- 2027, and to physicians and nursing facilities from 2017-2022. The proposed rule would allow states to make new supplemental provider pass-through payments during a time-limited period when states are transitioning populations or services from fee-for-service to managed care.

What Are State Options Under Current Medicaid Rules to Support Providers?

To address current fiscal challenges faced by providers, states have various options to support providers directly or by directing plans to do so. CMS has described some of these options in its COVID-19 frequently asked questions and an informational bulletin on Medicaid managed care options for responding to COVID-19.

State Options to Financially Support Providers

COVID-Related Rate Increases and Payment Methodology Adjustments. States can increase provider rates to account for increased costs or decreased service utilization as a result of the public health emergency. For example, states could increase payments to providers that are seeing an influx of Medicaid patients due to the emergency, incurring additional costs related to COVID-19 like personal protective equipment (PPE) or additional staff, or experiencing decreased utilization but an increased cost per unit due to allocation of fixed costs or increase in patient acuity. States also could increase payments for services delivered via telehealth. Payment increases can be in the form of dollar or percentage increases in base payment rates or fee schedule amounts, rate add-ons, or supplemental payments. Depending on the Medicaid authority that states are using for the covered service, states are using Home and Community Based Services Waiver (HCBS) Appendix K, Disaster-Relief State Plan Amendments (SPAs) and Section 1115 demonstration waivers to adopt COVID-related rate increases for providers.

Payment Increases through Upper Payment Limit (UPL) Adjustments. States may be able to make adjustments within the bounds of the UPL ceiling to direct supplemental payments to providers during the emergency or potentially make changes to UPL demonstrations already submitted to CMS to support UPL estimates for the fiscal year. With regard to proposed increases to nursing facility rates, CMS guidance related to UPL demonstrations recognizes that states can use either a cost-based approach or a payment-based approach to comply with the UPL ceiling. Under a cost-based approach, an increase in nursing facility costs due to the emergency can be accounted for in the UPL ceiling. Under a payment-based approach, states can adjust the UPL ceiling to the extent that Medicare payment equivalents have increased. CMS guidance says that it will work with states if they are concerned about UPL calculations, but the guidance also notes that states cannot use Medicaid Disaster Relief SPAs to waive applicable UPLs, and payments still must meet all applicable legal requirements.

Advance and Interim Payments. CMS has said in recent guidance that under state plan authority, states can make periodic interim advance payments to providers to help providers remain viable during the emergency so that they are available when the emergency period is over. The interim payment methodology must describe how states will compute interim payment amounts for providers (e.g., based on the provider’s prior claims payment experience), and subsequently reconcile the interim payments with final payments for which providers are eligible based on billed claims. CMS has said that it will consider such requests on an expedited basis.

Retainer Payments. States can request authority to make retainer payments to certain habilitation and personal care providers to maintain capacity during the emergency. Unlike interim payments, which are made before services are provided and subsequently reconciled so that providers are paid only for services actually rendered, retainer payments allow providers to continue to bill and be paid for certain services that are authorized in person-centered service plans to enable providers to maintain capacity when circumstances prevent enrollees from actually receiving those services. For example, during the current pandemic, enrollees may not be able to receive in-person services due to self-quarantine rules. Such retainer payments are limited to personal care or attendant service providers while the enrollee is hospitalized or absent from their home. CMS has permitted states to make retainer payments since 2000, in Olmstead guidance, to equalize treatment of personal assistance services and nursing facility services, for which bed hold payments are permitted. In the Olmstead decision, the U.S. Supreme Court found that states have community integration obligations under the Americans with Disabilities Act. The 2000 guidance applies to personal assistance services provided through HCBS waivers, and CMS’s Section 1115 COVID-19 demonstration waiver template allows states to request authority for retainer payments to habilitation and personal care providers such as adult day health centers that have closed due to social distancing orders and could go out of business and be unavailable to provide services after the pandemic. The National Association of Medicaid Directors has requested additional flexibility from CMS to enable states to make retainer payments to a broader set of providers using Section 1115 waiver authority.

Directed Payment Through MCOs. States can direct that managed care plans make payments to their network providers using methodologies approved by CMS to further state goals and priorities, including COVID-19 response. This strategy can address the scenario in which states are making capitation payments to plans, but providers are not receiving reimbursement from plans due to decreased service utilization while social distancing measures are in place and non-urgent services are suspended. For example, states could require plans to adopt a uniform temporary increase in per-service provider payment amounts for services covered under the managed care contract, or states could combine different state directed payments to temporarily increase provider payments, according to recent CMS guidance.

CMS explains that state directed increased payments for actual utilization of services can preserve the availability of covered services for enrollees during a time when providers may be experiencing dramatic utilization declines or incurring additional costs due to the public health emergency. The guidance also says that states may use directed payments to address increased use of telehealth or other approaches to maintain access to care for all enrollees or specific subgroups with specialized needs during the emergency. States can direct payments to a class of providers, such as dental, behavioral health, home health and personal care, pediatric, federally-qualified health centers, or safety-net hospitals, to support providers that may serve a high proportion of Medicaid enrollees and may be disproportionately affected by the public health emergency. Directed payments must be appropriate and reasonable compared to the total payments the provider would have received in the absence of the public health emergency. For states that have approved directed payment proposals, CMS guidance says that states wishing to make changes to such arrangements in light of COVID-19 can submit an amended directed payment preprint and/or contract and rate certification amendments to CMS.

Section 1115 Waiver Disaster Relief Funds. In prior emergencies, states have used Section 1115 waivers to create disaster relief funds to support Medicaid providers experiencing high levels of uncompensated care or fiscal instability. For example, disaster waivers approved in response to Hurricane Katrina included uncompensated care funds for affected states. During the COVID-19 emergency, CMS told Washington that it would continue to review the state’s request to use Section 1115 authority to create a Disaster Relief Fund to cover costs associated with the treatment of uninsured individuals with COVID-19, housing, nutrition supports and other COVID related expenditures. During state stakeholder calls, CMS has said it will consider other available federal funds before approving state requests for Section 1115 authority for certain activities. For example, CMS pointed to relief funds available through CARES as rationale for not approving Washington’s request to cover treatment costs for the uninsured through Medicaid. However, the amount and allocation of those funds is still a question.

State Adoption of Provider Payment Policies During COVID-19

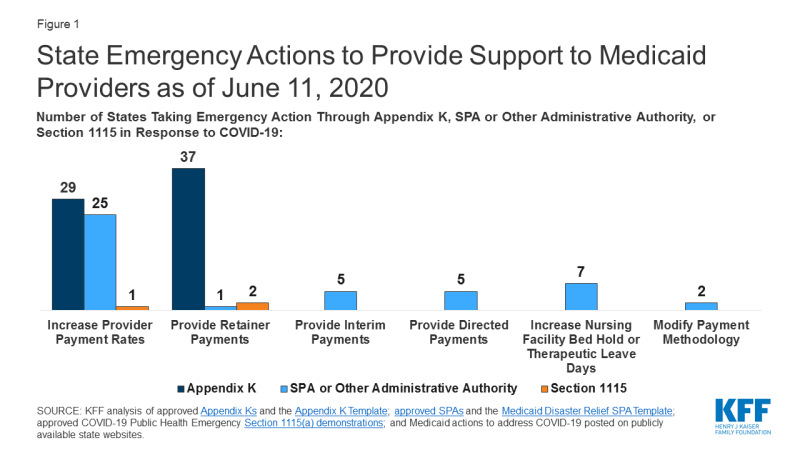

States have taken a number of actions to provide support to Medicaid providers in response to COVID-19 through Disaster-Relief State Plan Amendments (SPAs) and other administrative authorities, HCBS waiver Appendix K, and Section 1115 demonstration waivers. The Disaster-Relief SPA allows states to make temporary changes to their Medicaid state plans to address access and coverage issues during the COVID-19 emergency. States can also make changes through traditional SPAs (though no state to date has changed provider payment policies in response to COVID-19 using a traditional SPA) and can implement other changes under existing administrative authority that do not require SPA approval. Most Medicaid home and community-based services (HCBS) are provided through Section 1915 (c) waivers. Other states use Section 1115 to authorize HCBS that could have been provided under Section 1915 (c). States can use Section 1915 (c) waiver Appendix K to amend either of these HCBS waivers to respond to an emergency. CMS also developed a COVID-19 Section 1115 demonstration waiver template that identifies options for states to address the pandemic. The section below highlights the most common actions that states are taking regarding provider payment under these authorities (Figure 1).

The most common policy adopted by states to support providers across service type and authority is increasing payment rates. As of June 11, 2020, twenty-five states have taken action to increase provider payment rates for state plan services through Disaster-Relief SPA or other administrative authority, 29 states have done so for HCBS waiver services using Appendix K, and one state is using a Section 1115 waiver to increase rates for HCBS.

States adopting temporary provider payment rate increases for state plan services using Disaster-Relief SPA or other administrative authority are most frequently targeting nursing facility services. Some states limit the additional payments to nursing facilities or patients with a COVID-19 diagnosis, while others apply them to all nursing facilities to account for increased costs related to staffing, equipment and cleaning as a result of the emergency. For example, some states are increasing facility per diem payments by a flat dollar amount or percentage (AL, CA, CO, KS, KY, LA, MT, NC, NM, OH, SC, WA, VA). Alabama also is providing an additional add-on cleaning fee. Arkansas adopted temporary supplemental payments that increase weekly pay of direct care workers in nursing facilities, intermediate care facilities, and psychiatric treatment centers; the payments include a base supplemental payment according to number of hours worked and an additional tiered acuity payment for those working in facilities with COVID-19 positive patients. Michigan is providing a $5,000 per bed supplemental payment in the first month for COVID-19 regional hub nursing facilities to address immediate infrastructure and staffing needs and a $200 per diem rate increase in subsequent months to account for the higher costs of caring for COVID-19 patients. Four states (CO, IL, MT, WV) are increasing payment rates for other institutional settings, such as ICF/IDDs, in light of COVID-19, using Disaster-Relief SPA or other administrative authority.

A couple of states have adopted temporary payment rate increases that apply to a range of providers. In March, Arizona passed legislation to increase payment rates for Medicaid physicians and dental providers, funded through a hospital assessment. Massachusetts has set up an $800 million dollar fund for Medicaid providers impacted by COVID-19, including hospitals, nursing facilities, physicians, community health centers, HCBS, and community behavioral health providers. For example, as part of this initiative, Massachusetts is increasing hospital rates by 20% for COVID-19 care and 7.5% for other hospital care. In addition, Tennessee is seeking federal approval to distribute $5 million in targeted payments to behavioral health providers to preserve the community mental health and substance use disorder provider network for Medicaid beneficiaries.

Among the 29 states using Appendix K to temporarily increase provider payment rates for HCBS waiver services, the types of services commonly targeted for increases are residential habilitation, home health, respite, personal care, and nursing. Five of these states (KY, LA, NE, WA, WY) have broad approval to increase rates for any services in some or all of their HCBS waivers, up to a cap; the approved caps range from 15% to 50% of current rates. Some states are increasing HCBS payment rates only or particularly in case where waiver enrollees are COVID-19 positive; an example is Wyoming. In addition, six states (AK, AR, DC, MI, NC, OK) have increased payments for state plan HCBS using Disaster-Relief SPA authority, and Washington has done so using Section 1115 demonstration waiver authority. State plan HCBS rate increases include targeted case management (AK), day habilitation (AR), skilled and/or private duty nursing (DC, OK), and home health and adult care homes (NC). Arkansas’s temporary supplemental payments for direct care workers in nursing facilities, described above, also apply to direct care workers in assisted living facilities and those providing home health and personal care services in the community. Michigan is adding a supplemental payment for providers of personal care and behavioral health treatment technician in-person services. Washington’s Section 1115 demonstration waiver allows the state to increase rates for Community First Choice attendant care services by up to 50 percent to maintain provider capacity during the public health emergency.

Many states are adopting retainer payments for HCBS (the only services for which they are available). Thirty-seven states have established retainer payments through Appendix K to support HCBS waiver service providers and address emergency-related issues. Two states (WA and NH) have an approved Section 1115 waiver that authorizes retainer payments for personal care and habilitation services provided under state plan authority. Vermont is only state providing temporary retainer payments to a broader set of Medicaid providers through existing authority to set provider payments under its Section 1115 waver. Vermont has a unique managed care-like delivery system in which the state Medicaid agency contracts with another state entity that operates as a non-risk prepaid health inpatient plan. Vermont’s temporary payment model gives providers the option to combine fee-for-service reimbursement with prospective monthly payments that are intended to reimburse providers for the difference between their long-term average monthly Medicaid fee-for-service revenues and the actual amount of Medicaid fee-for-service claims payments issued to them for services they continue to provide. After the state of emergency ends, up to 10% of prospective payments may be subject to recoupment based on the provider’s performance on access to care and financial impact metrics, except that providers that have been ordered to close as a result of the emergency and cannot provide remote services will not be subject to recoupment.

Few states are using interim or advance payments to support providers. Five states (AZ, CA, GA, NC, OK) have received approval through a Disaster-Relief SPA to make interim payments to providers. In North Carolina, any Medicaid-enrolled provider may request that their reimbursement be converted to an interim payment methodology. Arizona is providing interim payments to Medicaid-enrolled hospitals, while Oklahoma is providing interim payments to rural/ independent Medicaid-enrolled hospitals. Georgia is making interim payments to skilled nursing facilities. California is providing interim payments for non-narcotic treatment program and specialty metal health services.

A small number of states are using directed payments through MCOs or are working with MCOs to increase funding to providers during the emergency. Arizona’s March legislation includes directed payments to hospitals, funded through a hospital assessment. New Hampshire directed its MCOs to provide temporary add-on payments to safety net providers including federally qualified health centers, rural health centers, critical access hospitals, and providers of residential substance use disorder treatment, home health, personal care, and private duty nursing services. Tennessee has adopted temporary payment rate increases for community-based residential, personal care, attendant care, personal assistance and intensive behavioral treatment stabilization and treatment services and a temporary per diem add-on to community-based residential and personal care payment rates to account for direct support staff hazard pay, overtime, and PPE costs using its existing directed payment authority; these services are provided under a Section 1115 HCBS waiver. Washington is identifying behavioral health providers at financial risk and directing its MCOs to reach out and offer support, such as advance payments, adjustments to capitated contracts, or other relief on a case-by-case basis, such as release of provider enhancement funds or budget-based contracts. Colorado is encouraging its managed care entities to use alternative funding strategies to support community mental health centers, such as sub-capitated arrangements. Rhode Island is seeking Section 1115 approval to make pass-through payments to MCOs during the public health emergency to effectuate rate increases to hospitals and HCBS providers and retainer payments to personal care, habilitation, rehabilitation, and adult day HCBS providers, to the extent those payments are approved by CMS.

A limited number of states are using nursing facility bed hold increases and other payment methodology adjustments. Seven states have received approval through a Disaster-Relief SPA to increase the number of days they will provide payment to nursing facilities to reserve the bed of a beneficiary that is hospitalized or otherwise temporarily absent. Three states (HI, KY, OH) have received SPA approval to increase the number of nursing facility bed hold days, and three states (LA, OK, PA) have received approval to increase the number of therapeutic leave days. Utah is increasing both bed hold and therapeutic leave days. Two states are making other payment methodology changes in response to COVID-19. Kentucky has received approval through a Disaster-Relief SPA to temporarily avoid applying per diem rate sanctions to nursing facilities that are unable to meet medical record review thresholds to validate assignment of patients to reimbursement groups based on acuity during the public health emergency. To aid drive-through testing facilities, Washington received approval through a Disaster-Relief SPA to unbundle payments and instead set a flat rate for the handling and/or conveyance of specimens for transfer from the patient (other than in an office) to a laboratory.

How are Provider Relief Funds Supporting Medicaid Providers?

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act and the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act provide $175 billion in provider relief funds to reimburse eligible health care providers for health care related expenses or lost revenues that are attributable to coronavirus. The funds are available to reimburse providers for health care related expenses or lost revenues that are attributable to coronavirus. Specifically, funds are available for building or constructing temporary structures, leasing properties, medical supplies & equipment including PPE and testing supplies, increased workforce and trainings, emergency operation centers, retrofitting facilities, and surge capacity.

To date, $112.4 billion of these funds have been allocated to specific sets of providers. The $112.4 billion consists of $50 billion that HHS allocated in April to Medicare fee-for-service providers based on each provider’s share of total 2018 net patient revenue from all sources, plus $22 billion in two rounds of funding to hospitals that treated a high number of COVID-19 patients; $10 billion to rural providers (including hospitals, health clinics, and health centers); $4.9 billion for skilled nursing facilities; $500 million to Indian Health Service programs; $10 billion to safety net hospitals; and $15 billion to Medicaid/CHIP providers who did not receive funds in the distribution to Medicare fee-for-service providers.

Prior to the new $15 billion allocation, there had been concern that Medicaid providers were disadvantaged in the funding distribution to date, both in the amount of funding received and delays in allocations. HHS estimates that about 62% of all Medicaid/CHIP participating providers received funds as part of the $50B general allocation to Medicare fee-for-service providers based on net patient revenue from all sources distributed in April. An analysis of those funds shows that the distribution disadvantaged providers less reliant on private insurance payments (and therefore likely more reliant on Medicaid). This resulted because private insurance reimburses at a higher rate than public payers. Provider relief funds specifically allocated to Medicaid providers were not announced until June 2020. HHS notes that some of the earlier targeted funding allocations, including base payments to rural health clinics and rural community health centers, accounted for providers with no reported Medicare claims. To help allocate funds to Medicaid providers, CMS asked states to provide data on Medicaid provider revenues. Due to data reporting challenges, CMS instructed states to not include data for self-directed direct care providers (HCBS) and PACE organizations, making it unclear whether those provider types were sufficiently reflected in the funding allocation.

HHS estimates that close to one million Medicaid/CHIP providers are eligible for grants from the new $15 billion allocation for those who did not receive funds in the distribution to Medicare fee-for-service providers. According to HHS, payments to each provider will be at least 2% of reported gross revenue from patient care. While this is the same level provided to Medicare fee-for-service providers in the April distribution, Medicaid providers may have more narrow operating margins than providers that rely more heavily on private insurance and Medicare so it is unclear if the allocation will be adequate. The final amount will be determined after providers submit data, including the number of Medicaid patients served. The submission deadline is July 20. HHS anticipates that provider types potentially eligible for this funding include pediatricians, OB-GYNs, dentists, opioid treatment and behavioral health providers, assisted living facilities, and other HCBS providers. However, Medicaid providers who received any amount of funding, no matter how small, from the April distribution to providers who participate in Medicare fee-for-service cannot receive additional funds from the new Medicaid provider allocation. This could disadvantage providers highly reliant upon Medicaid, such as community health centers. Funding will be distributed directly to providers and will not flow through state Medicaid agencies.

The remaining $62.6 billion from the provider relief fund may not be sufficient for the other purposes identified by HHS, including paying for COVID-19 treatment costs for the uninsured and supporting other targeted provider groups affected by COVID-19. HHS has allocated an unspecified amount of the provider relief fund to reimburse providers for the cost of providing COVID-19 treatment to uninsured people at Medicare rates, until funding is exhausted. KFF has estimated that hospital costs alone could run between $13.9 billion to $41.8 billion – not taking into account costs incurred for services provided in other settings. The decision to use a portion of the limited pool of provider relief funds to cover COVID-19 treatment costs for the uninsured (instead of through new or expanded insurance coverage options) means that less funding will be available for other purposes identified by Congress and for direct support for Medicaid providers.

HHS’s website refers to “future provider relief funding, and HHS has stated that it is working on an additional allocation for dentists. It is unclear whether there will be further, separate allocations for other provider groups. The HEROES Act passed by the House would allocate additional money to the provider relief fund, specify a reimbursement formula that weights Medicaid reimbursement at 200% when determining net patient revenue, and require that not more than $10 billion of the provider relief fund be used to reimburse uncompensated care costs.

What is the Outlook?

While states have some have taken some action under existing Medicaid authority to help bolster providers using increased payment rates, retainer payments, interim payments, directed payments, and some other methods, these actions have been largely directed to nursing facilities and some targeted community based long-term services and supports providers. Fiscal relief provided through the CARES Act to temporarily increase the Medicaid match rate by 6.2 percentage points may help states make such payment adjustments in the short term. However, as the economic crisis continues, more individuals are likely to enroll in Medicaid while state revenues are expected to decline significantly. States that had projections available in late April were already anticipating Medicaid budget shortfalls in the next fiscal year. In prior economic downturns, states have turned to provider rate cuts, so it may be difficult in the current economic realities for states to continue to maintain or increase provider rates. At the same time, Congress has enacted legislation with $175 billion in provider relief grants. While these grants were designed to serve many purposes, the initial allocation of funds was disadvantageous to Medicaid providers. HHS recently announced that $15 billion has been set aside to more directly support Medicaid providers, and an unspecified amount has been allocated to reimburse providers for COVID-19 treatment costs for the uninsured. However, it is not clear if the current provider relief fund allocations will be sufficient to meet providers’ needs resulting from the pandemic. Congress will likely continue to debate additional funding for states through Medicaid and for providers. Without additional fiscal relief, states may be limited in their ability to support Medicaid providers and provider relief grants may not be adequate.