Medicaid and the Opioid Epidemic: Enrollment, Spending, and the Implications of Proposed Policy Changes

The United States is facing an unprecedented opioid epidemic. In 2015, over 2 million people had a prescription opioid addiction and 591,000 had a heroin addiction.1 The epidemic has resulted in increased health care services utilization and a surge in opioid overdose deaths throughout the country, particularly in Appalachia and New England.

Medicaid plays an important role in addressing the epidemic, covering 3 in 10 people with opioid addiction in 2015. Medicaid facilitates access to a number of addiction treatment services, including medications delivered as part of medication-assisted treatment, and it allows many people with opioid addiction to obtain treatment for other health conditions. As of July 2017, 32 states have expanded Medicaid, with enhanced federal funding, to cover adults up to 138% of the federal poverty level ($16,643/year for an individual in 2017). This expanded Medicaid coverage has enabled many states to provide addiction treatment and other health services to low-income adults with opioid addiction who were previously ineligible for coverage.

However, the GOP’s Better Care Reconciliation Act (BCRA) proposes to restructure the Medicaid program through a per capita cap or block grant, to phase out the enhanced federal funding for the Medicaid expansion population, and to remove the requirement that Medicaid expansion plans cover addiction treatment. The BCRA also appropriates $4.972 billion each year over 9 years for state grants for substance use disorder and mental health treatment and recovery support services. However, even with the additional grant funding, the reduced federal funding for Medicaid could lead to reductions in Medicaid eligibility and coverage of services, affecting state efforts to address the opioid epidemic.

This issue brief provides information on the number of Medicaid enrollees with opioid addiction, Medicaid spending on these enrollees, and the implications of the BCRA as states work to combat this public health crisis. Drawing on state-level data available for FY 2013, this brief provides insight into Medicaid’s role, but from a time predating the expansion and current focus on the opioid epidemic. Thus effects shown here will undoubtedly understate Medicaid’s role today, but provide insight into the scope of Medicaid’s impact on the opioid addiction challenge.

How many Medicaid enrollees have opioid addiction?

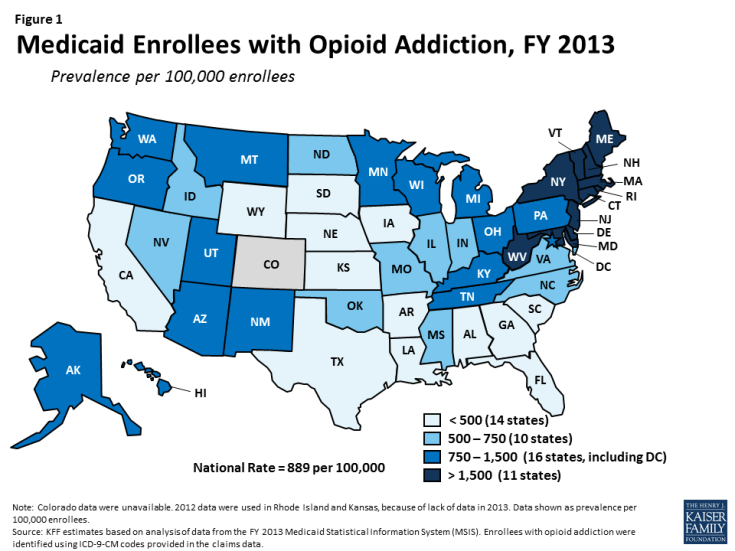

In FY 2013, there were 636,000 people enrolled in Medicaid with opioid addiction2, amounting to a prevalence of 889 per 100,000 (Table 1 and Figure 1). The number of Medicaid enrollees with opioid addiction ranged from a low in South Dakota of under 300 people to a high in New York of over 114,000 people. The prevalence of opioid addiction within the Medicaid population also varied across states, ranging from fewer than 300 per 100,000 enrollees in Arkansas, South Dakota, Texas, Nebraska, and California to over 3,000 per 100,000 enrollees in Vermont, Connecticut, Maine, and Massachusetts (Table 1). However, these counts are from before Medicaid expansion took effect; since the expansion likely extended coverage to many people with opioid addiction, a larger number of people with this problem are likely now covered by Medicaid in states that expanded their programs.

How much does Medicaid spend on enrollees with opioid addiction?

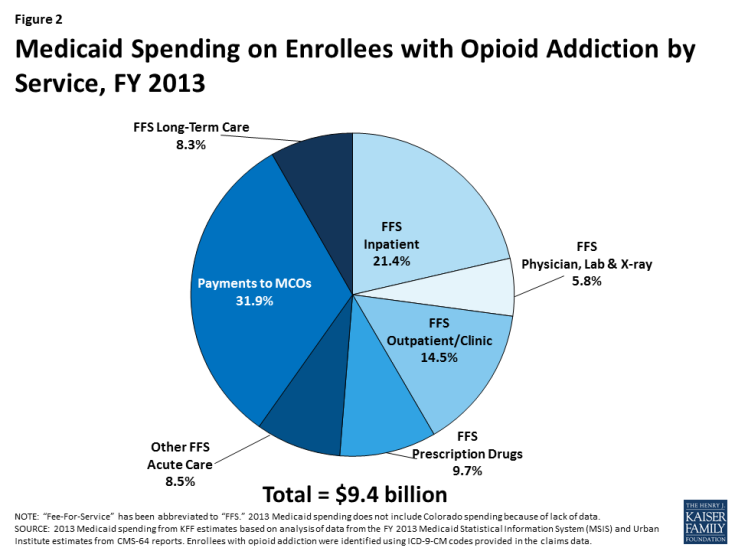

Medicaid covers a broad range of services for people with opioid addiction, spending $9.4 billion on their care in FY 2013. Medicaid provides both addiction treatment services, such as inpatient detoxification, intensive outpatient treatment, and medication-assisted treatment, as well as other services for health conditions either associated with or independent from opioid addiction.3 Many of these services are complex and often expensive. Approximately one-third (31.9%) of this spending was for payments to Medicaid managed care organizations. The remaining spending was through fee-for-service (FFS) arrangements and included inpatient treatment (21.4%); outpatient treatment (14.5%); prescription drugs (9.7%); long-term care (8.3%); physician, laboratory, and x-ray services (5.8%); and other FFS acute care services (8.5%) (Figure 2). Because these data are also from before the Medicaid expansion, total Medicaid spending on enrollees with opioid addiction has likely increased since 2013 as more people with the problem gained coverage in recent years.

How would the BCRA affect states’ ability to address the opioid epidemic?

Medicaid remains on the front lines for treatment of opioid addiction providing $9.4 billion in spending for enrollees with opioid addiction in 2013 and undoubtedly more today as the epidemic increases and coverage of the expansion population boosts Medicaid’s role. On July 13th 2017, the Senate released a revised discussion draft of the BCRA, which would change the structure of the Medicaid program substantially. Currently, the federal government matches state Medicaid spending with no pre-set limit. The BCRA would significantly reduce federal spending provided to states for the Medicaid program through a per capita cap, or at the state option, a block grant for expansion adults and other non-elderly non-disabled adults.4 It would also phase out enhanced federal financing for the Medicaid expansion population and remove the requirement that all Medicaid expansion plans cover addiction treatment. These changes will likely lead to decreases in eligibility, coverage, provider payments, and access to care.

In 2015, 1 out of 5 people with opioid addiction were uninsured, in part because many of these people lived in states that had not expanded Medicaid.5 Ending the federal enhanced support for the expansion and imposing a per capita cap on Medicaid will not facilitate expanding coverage to the uninsured. The Senate proposed $4.972 billion appropriation per year for 9 years will likely not fill this hole.

In addition to the Medicaid provisions, the BCRA also appropriates $4.972 billion each year from FY 2018 through FY 2026 to provide grants to states for substance use disorder treatment and recovery support services for individuals with substance use disorder or mental illness.6 The $4.972 billion per year for 9 years is an increase from $2 billion for state grants for FY 2018 alone, as proposed in the original draft of the BCRA released in June 2017. Several senators from states more heavily hit by the opioid epidemic had taken issue with the $2 billion appropriation in the BCRA, saying that it would not meet the amount needed to adequately address this public health crisis.7 These funds would increase capacity to address the epidemic but will likely fall short of the financing that accompanies increased coverage through Medicaid or other means.

People with opioid addiction often have health issues that abetted in, have been borne from, or are independent from their substance use and misuse. These include heart conditions, hypertension, asthma, hepatitis, sexually transmitted infections, and mental illnesses, such as depression.8 The $9.4 billion that Medicaid spent in FY 2013 was for a broad range of services, not solely for addiction treatment, reflecting the complex health profile of a person with opioid addiction. However, state grants from the appropriation are intended only for addressing substance use disorder treatment services and recovery support services for substance use disorders and mental illness, and would most likely be awarded to providers that are unable to address other health issues.

Of particular note, the $9.4 billion that Medicaid spent on enrollees with opioid addiction in FY 2013 does not include any of the very expensive drugs that effectively cure hepatitis C, such as Sovaldi, Harvoni, and Viekira Pak, as these drugs launched after FY 2013. Because these drugs cost tens of thousands of dollars per treatment per person and because the disease is prevalent among those addicted to opioids,9 spending on people with opioid addiction is very likely higher in FY 2014 than in FY 2013, even before taking into account the increase in the number of people with opioid addiction during this period. Hepatitis C is a blood borne virus, most frequently now spread through shared intravenous needles.10 Although drugs are now on the market that effectively cure hepatitis C, a person can contract the virus again if reintroduced, allowing the virus to continue to spread.11 As a result, addressing hepatitis C without addressing the opioid epidemic will allow the virus to live on, not only allowing for unfavorable health outcomes, but adding avoidable costs to the entire health care system.

Looking Ahead

The opioid epidemic has led to substantial health complications, increased health care services utilization, and considerable societal costs. Medicaid has played a critical role in addressing the epidemic by facilitating access to addiction treatment services, including medication-assisted treatment. Medicaid has also facilitated access to other health services for enrollees with opioid addiction, many of whom have complex health and psychosocial needs.

However, proposed changes to the Medicaid program in the BCRA could significantly affect states’ ability to combat this issue. In response to decreases to federal Medicaid financing, states may limit Medicaid eligibility, trim benefit packages and remove optional services, or decrease provider payment rates, all of which may limit access to medical, mental health, and addiction treatment services for individuals with opioid addiction. Although the BCRA allots additional funding for addiction treatment and recovery support services, this funding may not adequately compensate for the decreases in Medicaid spending proposed in the bill. As a result, there may be substantial unmet need for treatment among individuals with opioid addiction, further exacerbating this public health crisis.

| Methodology |

| This analysis is based on KFF estimates from the 2013 Medicaid Statistical Information System (MSIS) and Urban Institute estimates from CMS-64 reports. We adjusted MSIS spending to CMS-64 spending to account for MSIS undercounts of spending. Due to differences in the way CMS-64 and MSIS handle spending for managed long-term services and supports (MLTSS) and increased use of MLTSS in Medicaid, we have revised our methodology of adjusting MSIS to CMS-64. As a result, spending in this note are not comparable to previously published KFF analysis of Medicaid spending amounts from the MSIS.

Because FY 2013 MSIS data were unavailable for Rhode Island, and only one quarter was available for Kansas, we used 2012 MSIS for both of these states, aligned to 2013 CMS-64 spending. Data for Colorado were unavailable. We used the following ICD-9-CM codes in the non-prescription drug claims data to identify beneficiaries diagnosed with opioid addiction: 304.0X (opioid type dependence), 304.7X (combination of opioid type drug with any other drug dependence), 305.5X (nondependent opioid abuse), and 965.0X (poisoning by opiates and related narcotics). Because ICD-9-CM codes identify diagnosed health problems, it is possible that we are undercounting the true number of beneficiaries with opioid addictions. Additionally, although it is possible that we are including beneficiaries with serious opioid use problems who may not be addicted, we included them in this analysis, because we are interested with Medicaid’s interaction with the opioid epidemic overall. |

| Table 1: Medicaid Enrollees with Opioid Addiction, FY 2013 | ||

| State | Medicaid Enrollees with Opioid Addiction (Count rounded to nearest 100) | Medicaid Enrollees with Opioid Addiction (Prevalence Per 100,000) |

| Expanded Medicaid | ||

| Alaska | 1,200 | 881 |

| Arizona | 14,900 | 894 |

| Arkansas | 1,100 | 159 |

| California | 35,700 | 292 |

| Colorado | N/A | N/A |

| Connecticut | 27,600 | 3,255 |

| Delaware | 7,200 | 2,781 |

| District of Columbia | 2,500 | 984 |

| Hawaii | 2,700 | 872 |

| Illinois | 18,500 | 604 |

| Indiana | 9,300 | 718 |

| Iowa | 2,100 | 321 |

| Kentucky | 9,500 | 1,007 |

| Louisiana | 6,500 | 488 |

| Maryland | 33,400 | 2,834 |

| Massachusetts | 55,900 | 3,553 |

| Michigan | 20,500 | 889 |

| Minnesota | 15,900 | 1,379 |

| Montana | 1,100 | 777 |

| Nevada | 2,700 | 651 |

| New Hampshire | 3,200 | 1,867 |

| New Jersey | 19,300 | 1,549 |

| New Mexico | 6,700 | 993 |

| New York | 114,200 | 1,886 |

| North Dakota | 500 | 607 |

| Ohio | 34,300 | 1,261 |

| Oregon | 10,100 | 1,320 |

| Pennsylvania | 23,100 | 901 |

| Rhode Island | 3,300 | 1,696 |

| Vermont | 6,400 | 3,094 |

| Washington | 10,700 | 753 |

| West Virginia | 7,500 | 1,723 |

| Did Not Expand Medicaid | ||

| Alabama | 5,200 | 463 |

| Florida | 18,700 | 433 |

| Georgia | 6,900 | 347 |

| Idaho | 1,600 | 530 |

| Kansas | 1,700 | 392 |

| Maine | 12,700 | 3,396 |

| Mississippi | 3,900 | 501 |

| Missouri | 7,600 | 668 |

| Nebraska | 700 | 249 |

| North Carolina | 13,300 | 707 |

| Oklahoma | 6,600 | 665 |

| South Carolina | 3,500 | 319 |

| South Dakota | 300 | 200 |

| Tennessee | 13,500 | 864 |

| Texas | 10,500 | 202 |

| Utah | 3,200 | 823 |

| Virginia | 6,000 | 524 |

| Wisconsin | 12,200 | 957 |

| Wyoming | 300 | 390 |

| SOURCE: KFF estimates based on analysis of data from the FY 2013 Medicaid Statistical Information System (MSIS). Colorado data were unavailable. 2012 data used for Rhode Island and Kansas. See Methodology for details. | ||