COVID-19 Risks and Vaccine Access for Individuals Experiencing Homelessness: Key Issues to Consider

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, people experiencing homelessness have faced a unique set of challenges in protecting themselves and their families from the virus. People experiencing homelessness are already at higher risk for COVID-19 due to underlying health risks and other factors, while homelessness itself creates barriers to meeting social distancing guidelines and accessing testing and treatment. As with other congregate settings, shelters are at high risk for COVID-19 spread. Individuals who are unsheltered face additional risks from the cold weather and lack of access to hygiene and sanitation facilities. This brief explores issues related to risks related to COVID-19, vaccine priority in state plans, and other policy options that affect access to vaccines for people experiencing homelessness.

COVID-19 Risks for People Experiencing Homelessness

As of January 2020 (the latest comprehensive data available, but prior to the pandemic), approximately 580,000 people in the U.S. were experiencing homelessness – about 18 out of every 10,000 people on a given night (Appendix Table 1). The majority are individuals, but 30% are people in families. Nearly one in five (21%) are chronically homeless. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) considers an individual to be homeless if he or she lives in an emergency shelter, transitional housing program (including safe havens), or a place not meant for human habitation, such as a car, abandoned building, or on the streets. According to point-in-time data on homelessness from HUD, homelessness increased by 2.2% in 2020, marking the fourth year of national increases after long-term downward trends in homelessness since 2007. Data show there were higher rates of homelessness among people of color, specifically among Black or African American people, American Indian and Alaska Native people, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander people, and Hispanic or Latino people. For example, African Americans account for approximately 12 percent of the general population but 39 percent of people experiencing homelessness. Fifty-four percent of people experiencing homelessness are in four states (California, New York, Florida, and Texas) and over a quarter (28%) are in California alone.

Because many people who are homeless have underlying medical conditions, they may also be at higher risk for severe illness from COVID-19. Data and research show that people who are homeless have a range of health conditions ranging from physical and mental health problems to substance use conditions and tri-morbidity (co-occurring physical health, mental health, and substance use disorder challenges). These challenges present at higher rates for the unsheltered homeless populations. In particular, people experiencing homelessness are more likely to suffer from diabetes, heart disease, and HIV compared to the general population. People with these conditions face (or may face) a greater risk of developing severe illness from COVID-19 or of dying from COVID-19.

Homelessness services are often provided in congregate settings that can lead to rapid spread of infection. As of January 2020, more than six in ten (61% or 354,386) people experiencing homelessness were sheltered, meaning they used an emergency shelter, safe haven, or transitional housing program. While similar data for 2020 are not available, data show that in 2018, 1,446,000 people experienced sheltered homelessness at some time during the year, four times the number that were counted as sheltered homeless in January 2018. Early in the pandemic, a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) study of residents and staff members from five homeless shelters in Massachusetts, California, and Washington found that high proportions of residents and staff members had positive test results for COVID-19. Updated guidance from CDC on responding to COVID-19 for homeless populations calls for communication and coordination among community partners and identifies strategies to reduce transmission at homeless shelters, such as reconfiguring the layout to maintain social distancing among residents and staff, identifying overflow sites to reduce crowding, developing policies and locations for isolating people with COVID-19, ensuring staff who have contact with residents with COVID-19 wear personal protective equipment (PPE), and improving ventilation systems.

Unsheltered people experiencing homelessness are also at high risk from COVID-19. As of January 2020, approximately 226,000 people (or 39% of the total homeless population) were unsheltered, meaning these individuals sleep outside and in other locations not meant for human habitation. According to the CDC, while outdoor settings may allow people to increase physical distance between themselves and others, sleeping outdoors often does not provide protection from the environment, adequate access to hygiene and sanitation facilities, or connection to services and health care. CDC provides specific guidance to respond to COVID-19 for unsheltered homeless populations that includes strategies for training outreach staff on how to help prevent people from becoming sick and on how to link those with symptoms to medical care. The guidance also includes considerations for unsheltered homeless in encampments such as allowing for space between sleeping quarters or tents and working to improve sanitation.

National data related to testing, cases and deaths for those experiencing homelessness are not available. One website has compiled overall deaths from people experiencing homelessness and has added available data for 18 cities or counties reporting data on COVID-19 deaths among people experiencing homelessness. While the data are not official counts and are likely undercounts of actual deaths due to COVID-19 among this population, they provide some information specific to this population. For example, as of the end of October, the New York City Department of Homeless Services reported that 104 homeless people had died from COVID-19, including 95 sheltered individuals. While the overall counts appear to be small, analysis of the NYC data deaths for sheltered homeless per 100,000 were 75% higher than the overall rate for New York City. In Los Angeles County, as of March 8, 2021, there were 7,015 cases and 190 confirmed deaths for people experiencing homelessness out of an estimated population of 66,000. DC reported that as of March 9, 2021, there have been 521 reported positive cases of COVID-19 among people in homeless shelters and 25 individuals in the Homeless Services System have died from COVID-19. Los Angeles, Orange County, CA and Phoenix, AZ reported a surge in deaths among people experiencing homelessness in 2020; however few deaths were directly attributed to COVID-19 in these localities. The Los Angeles report showed a 25% increase in deaths from January to July 2020 compared to the same months in the prior year, but also found that a sharp increase in drug overdoses accounted for most of the increase and COVID-19 was the fifth leading cause of death among people experiencing homelessness. Some news reports indicate that the pandemic may have significantly limited access to facilities and services that may have prevented these deaths. One advocate noted that people who are homeless do not receive autopsies and another researcher noted that housing status is not listed on most death certificates or hospital records so deaths attributable to COVID-19 among people who are homeless are likely undercounted.

Data from health centers that primarily treat patients who are homeless show rates of positive tests and vaccines similar to overall health centers. Health care for the homeless (HCH) grantees are community health centers that receive funding to treat patients who are homeless. Some HCH grantees receive funding to treat only people experiencing homelessness while other HCH grantees treat both housed and unhoused patients. Cumulative data through January on COVID-19 testing and vaccinations show that HCH clinics have a similar share of individuals who test positive for COVID-19 relative to all health centers (12% compared to 13%) and a similar share of those receiving both COVID-19 vaccine doses was lower (27.7% compared to 29.5%). Additionally, the National Health Care for the Homeless Council has partnered with CDC to collect and report data from universal testing events at shelter or encampment-based service sites during the pandemic. There were 557 total testing events that participated and submitted data as of March 2021 showing a 6.1% positivity rate for clients, presumably lower than the rate at health centers because these were universal testing events.

Vaccine Prioritization, Access and Coverage Issues for Those Experiencing Homelessness

While federal guidance on COVID-19 vaccine allocation does not explicitly include people experiencing homelessness among the priority populations, it acknowledges higher transmission rates in congregate settings. In December 2020, the CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended that states prioritize certain at-risk populations for initial vaccine allocations, including health care workers and long-term care residents in phase 1a, people ages 75 and older and frontline workers in phase 1b, and people ages 65-74 and younger adults with high-risk medical conditions in phase 1c. Other ACIP guidance notes that states may choose to include people who reside in congregate living facilities, such as correctional or detention facilities and homeless shelters, along with priority groups in phases 1b and 1c due to “their shared increase risk of disease.”

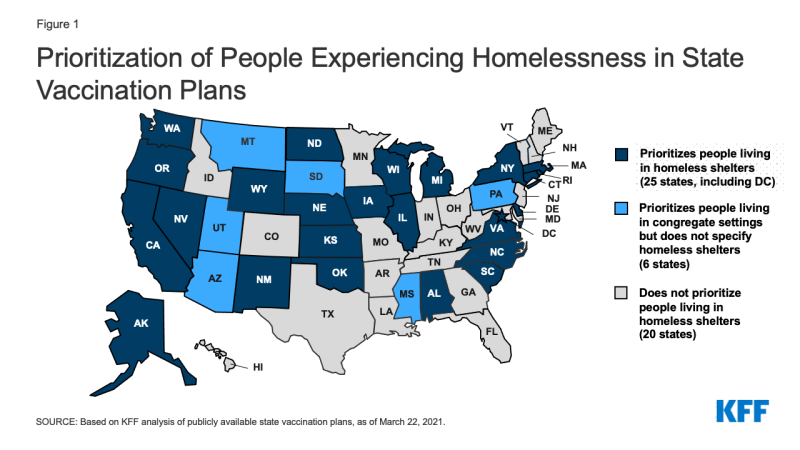

About half of states include people experiencing homelessness in their state vaccination plans. Although people in congregate settings face increased risk of contracting COVID-19, only 25 states explicitly prioritize residents in homeless in shelters for COVID-19 vaccine allocation while another six states prioritize people living in congregate settings, but do not specify homeless shelters (Figure 1). Only Massachusetts and Oregon include people in homeless shelters in their phase 1a group. The remaining states include people in homeless shelters in phase 1b or 1c. Oregon also includes people experiencing homelessness (those who are unsheltered) in phase 1b and Nevada includes people experiencing homelessness, both sheltered and unsheltered, in phase 1c. With supplies of the COVID-19 vaccine still limited, states are phasing in eligibility for the vaccine, and different groups become eligible for the vaccine at different times. As of March 22, 2021, people living in homeless shelters were eligible for the vaccine in 21 states.

Outreach and incentives can help to encourage take-up of vaccines. As noted above, how states prioritize groups for the COVID-19 vaccine will have implications for access for people experiencing homelessness. State plans have been evolving over time and more states are including individuals in homeless shelters as a priority. In addition, CDC has stated that the newly approved, 1-dose Johnson & Johnson vaccine may be desirable for people experiencing homelessness for whom scheduling a second dose would be difficult and because the vaccine is easier to transport and store. Specific outreach strategies that account for a high prevalence of mental health issues and potential mistrust of the health care system will help to ensure access to and take-up of vaccines. Advocates for people experiencing homelessness also have said incentives such as gift cards, socks, or other basics could be used to help encourage take-up of vaccines. Massachusetts received a $25 million grant from CDC for an effort to reduce barriers to vaccination in hard-hit areas; of that amount $3 million will be used to fund organizations to administer vaccines to groups “not effectively reached by other outreach efforts,” including homeless people living on the streets or in encampments.

An initiative to provide direct allocation of COVID-19 vaccine to health centers will help reach vulnerable populations, including people experiencing homelessness. As part of an effort to increase equity in vaccine distribution, the Biden administration recently launched the Health Center COVID-19 Vaccine Program, which provides designated health centers direct allocation of COVID-19 vaccines. The initial phase of the program allocated 1 million doses to 250 health centers across the country that serve a significant number of particularly vulnerable populations, including people experiencing homelessness, Of the initial 250 health centers, more than one-third (35%) are HCH grantees. With vaccine supplies increasing, an additional 700 health centers were invited to participate in the program on March 11, 2021.

A number cities are also using mobile teams to conduct outreach and administer vaccines for people experiencing homelessness. For example, in Enid, OK, Gainesville, FL, Berkeley, CA, Louisville, KY, Honolulu, HI and Sacramento, CA mobile teams with staff from health departments, fire rescue and other public health groups are going to shelters, places where people who are homeless get food and areas where unsheltered homeless individuals live to administer vaccines. In DC, the Department of Human Services is partnering with the entity that is the main provider of medical care to the homeless to administer vaccines in homeless shelters. These efforts recognize people who are experiencing homelessness are not able to sign up with a computer for a vaccine appointment and then get to that appointment.

Medicaid can provide coverage and access to care (including COVID-19 testing and treatment) for homeless populations, particularly in states that have adopted the expansion. Broader coverage exists for people experiencing homelessness in states that have adopted the ACA Medicaid expansion. Based on data from HCH programs in 2018, the overall rate of uninsured was 34%; however, in states that adopted the expansion, the rate of uninsured patients was 23% compared to 66% in non-expansion states; however, even in expansion states the rate of uninsured at HCH programs range because all those who are eligible for Medicaid may not be enrolled. In focus groups following the implementation of the ACA, providers serving people experiencing homelessness reported that the coverage gains from expanding Medicaid enabled patients to access many services that they could not obtain while uninsured, including some life-saving or life-changing surgeries or treatments. For people experiencing homelessness who are uninsured, The American Rescue Plan provides a new state option for coverage of COVID-19 treatment services, without cost-sharing. The COVID-19 uninsured testing group was created by the FFCRA and is available at state option, with 100% federal matching funds, during the PHE, the American Rescue Plan adds COVID-19 treatment services to this group.

Medicaid can also provide some services and supports to help people experiencing or at risk of experiencing homelessness in responding to COVID-19. For example, while Medicaid cannot pay directly for housing, Medicaid can pay for community transition costs to facilitate individuals transitioning from an institutional or other congregate living arrangement (such as a homeless shelter) to a community-based living arrangement. Medicaid coverage of community transition as well as respite care may be helpful in addressing temporary housing needs for individuals during the pandemic.

States can also address the health needs of people experiencing homelessness by requesting temporary disaster relief authorities in Medicaid/CHIP. As of January 2020, 44 states have received authority through an approved 1135 waiver to allow provision of services in alternative settings, such as homeless shelters or mobile units. Authority for these waivers is tied to the duration of the national emergency and the public health emergency declarations. Additionally, Rhode Island received approval from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) for a disaster relief SPA that added an emergency case management benefit for Medicaid beneficiaries experiencing homelessness.

Looking Ahead

While issues related to health care access for people experiencing homelessness are not new, the pandemic has exacerbated many challenges faced by this population and the total numbers of people experiencing homelessness has likely increased. People experiencing homelessness, particularly those receiving services in homeless shelters, are at greater risk of severe illness or death from COVID-19; however, national data about cases and deaths for this population are not known. Looking ahead, ensuring access to and take-up of the COVID-19 vaccine will be an important step in mitigating the health effects of COVID-19 for people experiencing homelessness. The approval of the 1-dose Johnson & Johnson vaccine along with distribution to clinics serving people experiencing homelessness and targeted outreach will help to ensure access to and take-up of vaccines. Finally, as the economic effects of the pandemic continue, recent polling shows that 16% of adults report they have fallen behind on their rent or mortgage and other data show that 7% of adults have no confidence that their ability to make next month’s housing payment. To help address problems of housing insecurity and homelessness, the American Rescue Plan provides $5 billion for housing vouchers for those at high risk of becoming homeless, $5 billion for homelessness assistance and supportive services and more than $20 billion in funding for low-income renters at risk of losing housing.