COVID-19 Issues and Medicaid Policy Options for People Who Need Long-Term Services and Supports

| Key Takeaways |

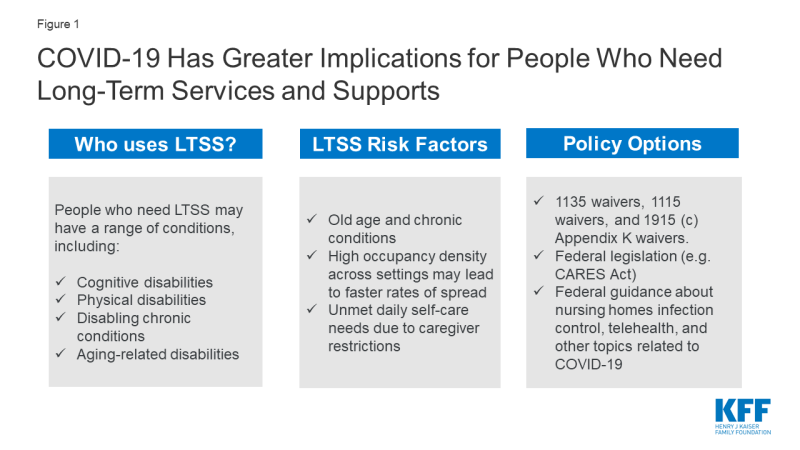

The COVID-19 pandemic has greater implications for people who utilize long-term supports and services (LTSS), including seniors and people with disabilities & chronic illnesses, compared to the general population. This issue brief presents state-level data on LTSS users, including the 2.5 million people who receive HCBS through waivers, 1.3 million people in nursing homes, and 800,000 people in assisted living facilities. This brief also explores key issues and potential state and federal policy responses for LTSS users in light of the COVID-19 pandemic and Medicaid’s role as the primary LTSS payer.

|

Introduction

While the COVID-19 pandemic is a global crisis, it may have greater implications for people who utilize long-term supports and services (LTSS), including seniors and people with disabilities & chronic illnesses. As the primary payer for LTSS for millions of low-income Americans, Medicaid is poised to play an important role in the nation’s COVID-19 response for vulnerable populations. There is limited coverage for LTSS under Medicare and few affordable options in the private insurance market. State Medicaid programs must cover LTSS in nursing homes, while most home and community-based services (HCBS) are optional and covered through waivers that may target specific populations. This issue brief presents state-level data and explores key issues and potential state and federal policy responses for Medicaid LTSS users in light of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Populations at Risk and Key Issues

People who need LTSS are in both institutional and home or other community-based settings and have a range of conditions and needs. LTSS needs arise from a range of conditions, such as cognitive disabilities, like dementia or Down syndrome; physical disabilities, like multiple sclerosis or spinal cord injury; mental health disabilities, like depression or schizophrenia; and disabling chronic conditions, like cancer or HIV/AIDS. While COVID-19 has been shown to primarily impact adults, some children with special health care needs can be at risk of severe infection should they contract the virus, given that many of them have conditions that make them susceptible to compromised immune systems. Children with special health care needs may have asthma, depression, cerebral palsy, cystic fibrosis, diabetes, muscular dystrophy, brain injury, heart conditions, and epilepsy. Appendix Table 1 shows the distribution of LTSS users across institutional and community based settings. In 2016, Medicaid spending on HCBS was 57% of total Medicaid LTSS expenditures, exemplifying states’ gradual shifts away from institutional care over the last two decades.

People receiving LTSS in institutions are at increased risk for adverse health outcomes if infected with coronavirus due to old age, chronic health conditions, and high rates of occupancy density. Institutional LTSS include care provided in nursing homes, intermediate care facilities for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD), and institutions for “metal disease.” As of April 10, nearly 2,500 long-term care facilities are battling coronavirus infections, a 522% increase from the 400 facilities reported by the CDC on March 30. There have also been reports of other types of institutions with COVID-19 outbreaks, including a facility in Texas that serves people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. The high rates of infection in these facilities can be attributed to a number of factors, including high rates of occupancy density, which is as high as 90% in some states.1

Nursing home residents may have high levels of need, ranging from respiratory issues to cognitive and behavioral health needs, which contribute to their increased risk due to coronavirus. Sixteen percent of nursing home residents underwent respiratory treatment in 2017, which can be provided through respirators/ventilators, oxygen, or inhalation therapy. Given the implications of this virus on respiratory systems, these residents could be at higher risk of severe outcomes if they were to become infected. Nursing homes’ capacity to care for high-need patients, such as those with coronavirus, varies. Residents in nursing facilities are also at risk of being diagnosed with psychiatric disorders, with nearly 40 percent having experienced symptoms of depression.2 Visitor restrictions in nursing facilities, which are currently being implemented to lower the risk of exposure, may have negative impacts on residents’ mental health and increase the incidence of depressive symptoms. These health problems may be further exacerbated by fear, worry, or social isolation due to COVID-19.

Individuals receiving HCBS may also be at increased risk for adverse health outcomes if infected with coronavirus. HCBS encompass many different types of care, such as home health services, personal care services, and private duty nursing. Some people receive HCBS at home, while others may receive services elsewhere in the community, such as assisted living facilities, adult day health centers, and Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) centers, which provide integrated care for people dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. HCBS programs serve a range of populations, all of whom have varying levels of need. These include people with I/DD; people with physical disabilities, such as cerebral palsy or multiple sclerosis; seniors with Alzheimer’s disease and physical functional limitations associated with the aging process; and people with chronic illness such as HIV/AIDS. People who receive HCBS in settings with others are at greater risk for coronavirus infection, as there have been reports of outbreaks in settings such as assisted living facilities. Given that some community-based settings share similar characteristics to institutions, including issues related to occupancy density, outbreaks may occur.

LTSS users receiving care in the home and/or community rely on caregivers to help with daily self-care and household activities. LTSS provide assistance with self-care tasks (such as eating, bathing, and dressing), and household activities (such as meal preparation, medication management, and housekeeping). These services are essential to meet LTSS beneficiaries’ daily needs, many of whom often have substantial medical needs as well. In the U.S., the majority of LTSS is provided by unpaid caregivers – relatives and friends – at home.

LTSS may be restricted as caregivers take precautions to limit coronavirus exposure to the individuals they serve. The spread of coronavirus presents three major issues with regards to the LTSS caregiver workforce. First, if LTSS caregivers begin to get ill and are unable to provide care, there may be a severe shortage of LTSS available for those who need it. Secondly, evidence is growing that some people may be unknowingly infected with coronavirus and capable of transmitting the disease to others, while asymptomatic. Therefore, screening of direct care workers, who often must be in close contact with their patients, is important to containing the spread of the virus. This is especially true, given that many people who receive LTSS have chronic conditions and compromised immune systems, placing them at high risk for severe outcomes if infected. The third major issue is that LTSS depend on medical supplies that are currently in short supply. Healthcare settings across the country are running low on critical medical supplies, and healthcare providers are resorting to reusing gloves, gowns, and masks. Those receiving and providing LTSS are at risk from interruptions in access to medical supplies, which can interfere with the ability to manage daily health needs as well as prevent coronavirus infections.

State Policy Options Under Existing Authorities

States can adopt a variety of policy options to increase and support access to Medicaid LTSS during public health emergencies such as COVID-19. Examples of options under the major authorities are described below, and a detailed list is provided in Appendix Table 2. The state examples below are not an exhaustive list, and additional state approvals are regularly updated in our Medicaid emergency authorities tracker.

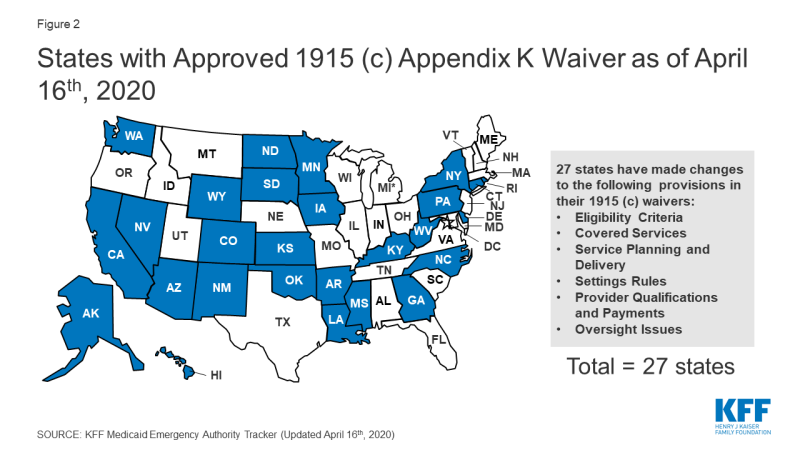

Section 1915 (c) waiver Appendix K enables states to modify policies to expand HCBS eligibility and services and support providers in emergencies (Figure 2). As noted above, most HCBS are provided through waivers. CMS has clarified that Appendix K also can be adopted by states with Section 1115 waivers that authorize HCBS, without an accompanying Section 1915 (c) waiver. Appendix K approvals can be retroactive to HHS’s January 2020 public health emergency declaration and effective for one year.

States can use Appendix K to expand waiver eligibility to a wider population and to offer additional services. For example, a waiver serving individuals with Alzheimer’s disease may be expanded to offer services to a broader aged population to forestall institutionalization in emergencies. States also are adjusting the amount, duration, or scope of regularly covered services to account for increased needs during an emergency.

States can use Appendix K to ensure uninterrupted access to HCBS during an emergency by extending waiver level of care renewals for up to 12 months, temporarily suspending prior authorization requirements, and extending medical necessity authorizations. States also can take steps to ensure that waiver enrollees continue to receive services if their usual setting is disrupted during an emergency. For example, states can temporarily modifying provider requirements to allow for day program services in individual homes if day centers are closed due to outbreak of contagious illness. States can temporarily allow payment for waiver services, such as communication supports and intensive personal care, for enrollees during an acute care hospital or short-term institutional stay.

States can address provider shortages during an emergency by allowing payment to family caregivers or legally responsible relatives and temporarily modifying minimum provider qualifications to allow neighbors or acquaintances to be service providers during the emergency. States also can support providers by temporarily increasing payment rates to attract more providers and/or to account for costs such as personal protective equipment (PPE) for home care workers and temporarily paying retainers to personal care assistants when enrollees are institutionalized up to 30 days.

Section 1135 and Section 1115 waivers may provide additional authorities to states in emergencies. Section 1135 authority is tailored to addressing emergency needs, such as sufficient health care items and services. For example, states can use Section 1135 waivers to expand access to HCBS in times of provider shortages caused by emergencies by temporarily suspending requirements for home health and hospice aide supervision by registered nurses or streamlining provider enrollment requirement for HCBS provided in the state plan benefit package. Section 1135 waivers also can allow states to waive fee-for-service prior authorization requirements and extend appeal deadlines for enrollees. On March 28, 2020, CMS issued blanket Section 1135 waivers, which apply throughout the U.S. healthcare system during the emergency that temporarily suspend some nursing facility certification requirements to provide additional surge capacity, free up inpatient hospital beds, and provide space for isolation and treatment of those with coronavirus. The blanket waivers also allow long-term care facilities to transfer residents to separate those with and without COVID-19 to provide care while limiting the spread of infection. Section 1115 waivers have been used in emergencies to expand eligibility for Medicaid LTSS by waiving the 30 day institutional stay requirement or asset transfer rules.

States also can adopt a variety of policies to respond to an emergency without the need for CMS approval. Existing Medicaid regulations allow states to streamline Medicaid enrollment, such as accepting self-attestation to establish spend down eligibility, and to extend renewal timeframes to preserve continuity of coverage. States also can use telehealth instead of in-person meetings for needs assessments for state plan HCBS, such as home health, personal care, or Community First Choice attendant services. States delivering services through MLTSS can use their authority to regulate health plans to ensure that enrollees have access to needed services during an emergency by directing plans to temporarily suspend out of network rules or expedite new prior authorization requests.

New Federal Policy Options and Guidance

Recently enacted federal legislation includes some provisions that can support state responses to the COVID-19 emergency. The Families First Coronavirus Response Act authorizes 6.2% enhanced federal Medicaid matching funds, provided that states meet certain requirements, such as maintaining eligibility standards and enrollment and covering coronavirus related testing and treatment without cost sharing. This enhanced federal funding may help states finance some of the policy options described above to expand HCBS eligibility and services during the emergency. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act allows certain providers other than physicians to certify the need for Medicaid home health services.3 The CARES Act also provides additional funding for Money Follows the Person demonstrations that support Medicaid beneficiaries moving from institutions to the community and extends the ACA requirement that states apply the institutional care spousal impoverishment rules when determining Medicaid HCBS eligibility through November 2020. The CARES Act also requires that at least $100,000,000 of a $200,000,000 appropriation to CMS be spent on nursing facility inspection programs, with priority for facilities in localities with community transmission of coronavirus.

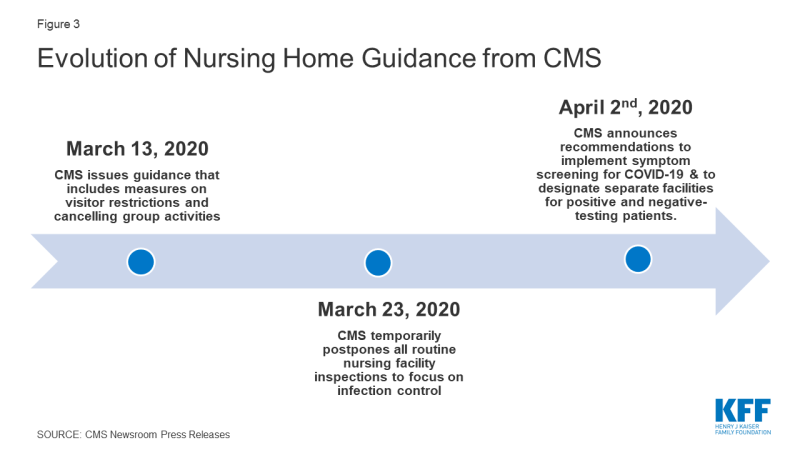

CMS has taken several actions to address the impact of COVID-19 in institutional LTSS facilities. On March 13, 2020, CMS issued a memo to State Survey Agency Directors that provided guidance on infection control and prevention of COVID-19 in nursing homes.4 This guidance included measures that restricted all visitors (with exceptions for compassionate care), volunteers and other nonessential personnel, and implemented active screening of residents and staff for fever and respiratory symptoms. On March 23, 2020, CMS announced that it is temporarily postponing all routine nursing facility inspections to focus solely on infection control and “Immediate Jeopardy” situations, which are situations in which a patient’s safety is placed in imminent danger. CMS also is recommending that 1) facilities administer their own self-assessments to determine whether they are prepared for an outbreak, and 2) residents and families ask facilities for results of the self-assessments. This guidance is based on CMS’s preliminary findings from its inspection of the Kirkland, Washington nursing home, the site of a COVID-19 outbreak affecting many residents and staff.5 CMS released further guidance on April 2nd, 2020 that includes recommendations to implement coronavirus symptom screening for all staff, residents, and visitors; use appropriate PPE when interacting with patients and residents, to the extent that it is available and used within the guidance of PPE conservation; and designate separate facilities for coronavirus negative residents from coronavirus positive residents and individuals with unknown coronavirus status.6 Notably, CMS has not provided guidance to nursing homes about reporting cases and deaths attributed to coronavirus in their facilities, which has led to a lack of reliable data and an inability to capture the extent of the issue.

Another high-risk population that the federal government has sought to address with new guidance are those in PACE programs. Nearly 50,000 people dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid receive integrated care through a PACE organization (Appendix Table 1), prompting CMS to issue guidance on March 17, 2020 that all PACE organizations establish, implement, and maintain a documented infection control plan, and personnel be given and trained on the use of personal protective equipment (PPE).7

CMS also has encouraged and expanded the use of telehealth instead of in-person visits. CMS guidance on how states can use their Medicaid programs to cover telehealth services highlights that states have significant flexibility to deliver covered services through telehealth and provides policy options for states to reimburse Medicaid providers that provide telehealth services.8 On March 13, 2020, CMS also expanded Medicare’s telehealth benefits under Section 1135 waiver authority and as required by the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act to allow beneficiaries to receive healthcare services without having to travel to a healthcare facility. The changes apply to those receiving skilled nursing facility services, home health, and hospice. This expansion of benefits will also allow Medicare beneficiaries to receive care for various services, including common office visits, mental health counseling, and preventive health screenings.9

Looking Ahead

State and federal policymakers are responding to a rapidly changing environment as the COVID-19 emergency progresses. Looking ahead, state budget pressures and a looming recession will present additional financial challenges and pressures for states. In the days and weeks ahead, nursing home capacity also will be challenged to care for patients discharged from hospitals, freeing acute care beds for subsequent patients in need of care while also striving to control the spread of infection. Ongoing challenges likely will result from COVID-19’s impact on direct care workers, which in turn may limit seniors and people with disabilities and chronic illnesses’ ability to receive services on which they depend to meet daily self-care and independent living needs. Greater access to coronavirus testing would allow for the identification of LTSS workers and others who may be asymptomatic but at risk of spreading the virus to vulnerable populations. Additionally, interruptions in access to medical supplies as a result of the COVID-19 emergency can interfere with people with disabilities’ ability to manage their daily health needs. As the pandemic continues, there will be a particular focus on people who need LTSS services — given their heightened risk and high rate of infection, severe illness, and mortality – and on policies to protect them and their caregivers.