5 Key Questions: Medicaid Block Grants & Per Capita Caps

Medicaid provides health and long-term care coverage to more than 70 million low-income children, pregnant women, adults, seniors, and people with disabilities in the United States. The program represents $1 out of every $6 spent on health care in the US and is the major source of financing for states to provide coverage to meet the health and long-term needs of their low-income residents. Medicaid is administered by states within broad federal rules and jointly funded by states and the federal government. President Trump and other GOP leaders have called for fundamental changes in the structure and financing of Medicaid. The basics of Medicaid financing as well as core program requirements and flexibility are discussed in these companion briefs. This brief outlines five key questions to consider as the debate moves forward as well as some potential implications of these changes for states, beneficiaries and providers.

1. What Medicaid Financing Changes are currently being considered?

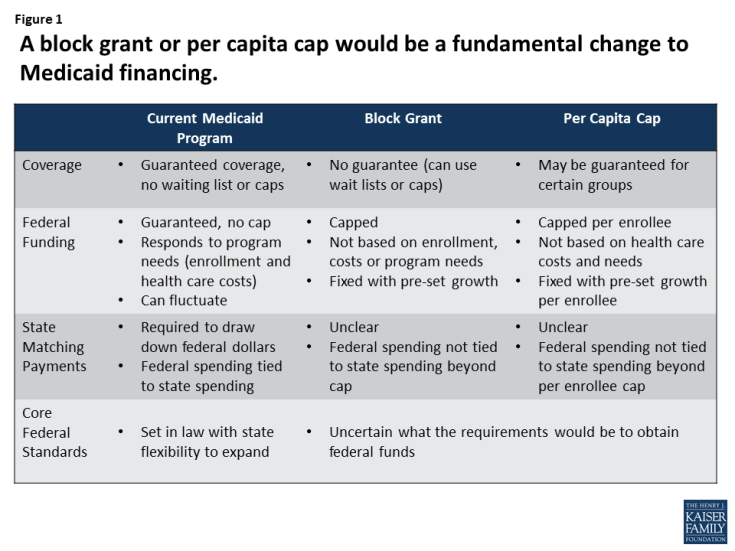

President Trump and other GOP leaders have called for fundamental changes in Medicaid financing that could limit federal financing for Medicaid through a block grant or a per capita cap. Unlike current law where eligible individuals have an entitlement to coverage and states are guaranteed federal matching dollars with no pre-set limit, the proposals under consideration could eliminate both the entitlement and the guaranteed match to achieve budget savings and to make federal funding more predictable. To achieve budget savings, federal funding limits would be set at levels below expected levels if current law were to stay in place. In exchange for these federal caps, proposals could allow states to eliminate the entitlement to coverage and impose enrollment caps or waiting lists or reduce eligibility levels or offer states other increased flexibility to design and administer their programs. Many proposals do not specify the rules for state matching payments or what core federal eligibility and coverage standards would be changed. (Figure 1)

2. How would a block grant work?

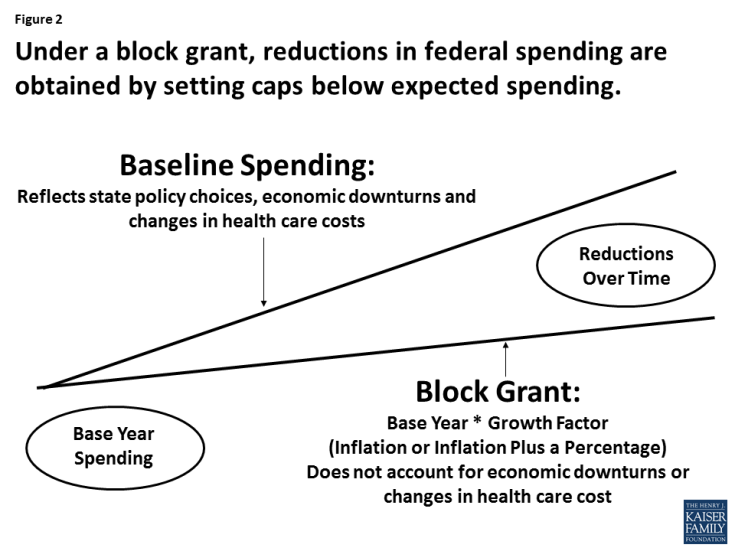

Under a block grant, states would receive a pre-set amount of funding for Medicaid. Typically, a base year of Medicaid spending would be established and then the cap would increase by a specified amount each year, typically tied to inflation or inflation plus some percentage. To generate federal savings, the total amount of federal spending would be less than what is expected under current law. Under current law, federal Medicaid spending matches states spending for eligible beneficiaries and services without a pre-set limit. If state spending increases due to increased enrollment or program costs, then federal spending increases as well. Under a block grant, if program costs exceed the federal spending cap due to increased enrollment during a recession or rise in health costs for example, states would have to increase state spending or reduce enrollment or services. (Figure 2)

Figure 2: Under a block grant, reductions in federal spending are obtained by setting caps below expected spending.

3. How would a per capita cap work?

Under a per capita cap, federal funding per enrollee would be capped. A base year of per enrollee spending would be determined and then that amount would increase over time by a pre-set amount (i.e. inflation or inflation plus a percentage). These per enrollee caps could be determined for all enrollees or separate caps could be calculated based on broad Medicaid coverage groups (children, adults, elderly and people with disabilities). States would receive the sum of the per enrollee amounts multiplied by the number of enrollees in each group. To achieve federal savings, per enrollee spending would be set to increase slower than expected under current law. Although this approach adjusts for enrollment it would still not address increases in health costs or changes in technology that increase per enrollee spending. (Figure 3)

Figure 3: Under a per capita cap, reductions in federal spending are obtained by setting caps below expected spending.

4. What Details Do You Need to Know to Understand these proposals?

What happens with the ACA Medicaid expansion? Proposals to change Medicaid financing are occurring at the same time as policy makers are also considering options to repeal and potentially replace the ACA. For states that have adopted the Medicaid expansion, Medicaid coverage and financing are at risk with repeal. From January 2014 through September 2015 states have claimed $93 billion in federal dollars tied expansion group enrollees that in the first quarter of 2016 covered 14.4 million adults of which 11.2 million were newly eligible. Enhanced federal dollars and gains in coverage are at risk with repeal. The magnitude of the effects will largely depend on what may replace the ACA and if any savings from repeal can be maintained by the state. For states that have not adopted the expansion the question is whether they are locked into that decision thereby resulting in a lower spending base than expansion states.

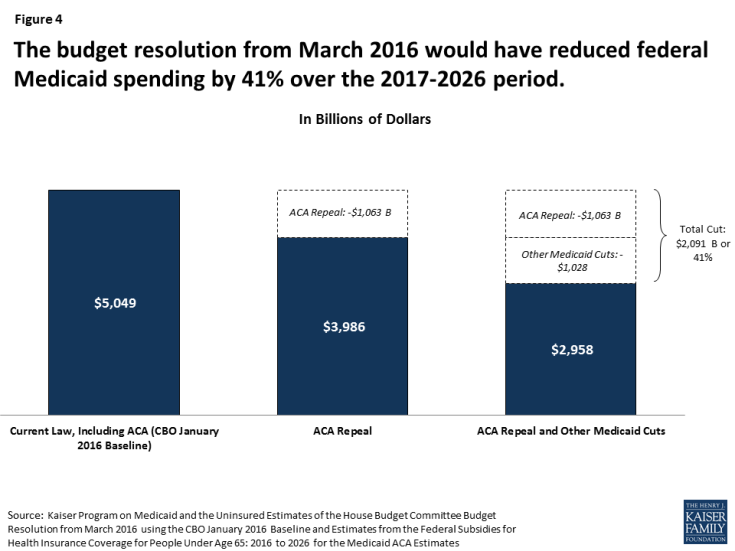

What are the federal savings targets? One key issue for either a block grant or per capita cap approach is understanding how much in federal savings are anticipated from the proposal. While states may gain additional flexibility to administer their programs, these new options are not likely to make up for significant cuts in federal spending and maintain coverage. Medicaid accounts for over half of all federal funds spent by states. Some proposals dating back to the House Budgets in 2011 and 2012 and the House Budget from 2016 included cuts of about 40% (including the ACA repeal and Medicaid caps in federal spending) over a ten year period (Figure 4). Analysis of the 2011 and 2012 proposals showed federal cuts of this magnitude could result in enrollment cuts of 25% to 35% due to just the Medicaid caps and up to 50% including the repeal of the ACA if states did not offset the federal reductions. The Congressional Budget Office estimates of the 2011 plan said the cuts would likely require states to reduce payments to providers, curtail eligibility for Medicaid, provide less extensive coverage to beneficiaries, or pay more themselves than would be the case under “current law.”

Figure 4: The budget resolution from March 2016 would have reduced federal Medicaid spending by 41% over the 2017-2026 period.

How would policy makers set the base year or starting point? A block grant or per capita cap model would set a base year of Medicaid financing for states. Policy makers would need to consider what payments or populations to include or exclude (such as disproportionate share hospital payments (DSH), Medicare premium amounts, enrollees eligible for limited benefits such as family planning, duals or home and community-based services only). If the base year is set based on actual spending from a prior year, this would lock-in historic spending and policy decisions. Decisions around the base year would need to address whether to include or exclude the ACA Medicaid expansion funding and whether the base would lock-in those choices around the ACA. Lack of administrative data could make determining a base year difficult.

Would states need to contribute state dollars for Medicaid? Whether states would still need to use state funds to access federal funds and whether there would be limits in the sources of state funds (such as limits to provider taxes) are critical to overall Medicaid funding. All states except Alaska use provider taxes (the majority of states have more than three provider taxes). Some proposals could require state matching dollars up to the cap, but others could provide states with a lump sum of federal money without state matching requirements. Reductions in state spending could compound the impact of federal spending reductions and have larger effects for enrollees and providers.

What new flexibility would states be granted? Medicaid financing reform proposals are often tied to promises of additional flexibility for states. Under current law, Medicaid balances core requirements and standards with state flexibility, accountability for federal dollars and beneficiary protections. Currently, all states offer additional coverage for children and additional benefits that are not required by the law. States have considerable flexibility to determine how to pay for and deliver services to beneficiaries, and most states impose nominal copayments for some populations or services. Some proposals have called for new flexibility to increase premiums and cost sharing, reduce benefits and impose work requirements but have not addressed eligibility or benefit requirements. These new flexibilities would primarily apply to adults and not the elderly and disabled populations that account for the majority of Medicaid spending. Proposals have not been specific about federal oversight and how states would be accountable for federal Medicaid dollars.

5. What are the implications of a block grant or a per capita cap?

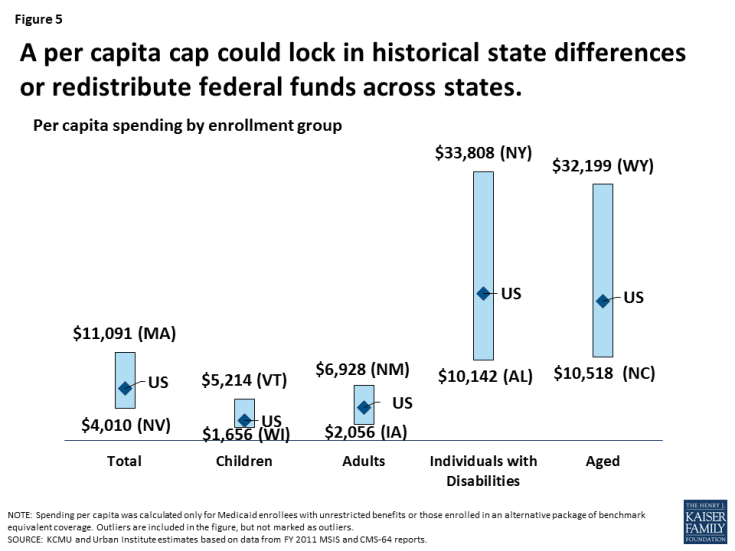

These financing designs could lock in historic spending patterns and variation in Medicaid spending across states. There is significant variation in Medicaid spending across states due to a number of factors including state policy decisions, but also state revenues, health care markets, and the demographics and demand for Medicaid services. Determining a base year and allowing for a fixed amount of growth would lock-in these historic variations in spending; however, alternatives to move to more uniform spending could result in redistributions of federal spending across states. Either option can result in states deemed “winners” or “losers”. (Figure 5) The magnitude of state variation will also be shaped by how the ACA Medicaid expansion is treated.

Figure 5: A per capita cap could lock in historical state differences or redistribute federal funds across states.

Limiting federal financing could save federal dollars but would be less responsive to state decisions and changing program needs. Under the current financing structure federal funds are tied to actual costs, program needs and state policy decisions. If medical costs rise, more individuals enroll due to an economic downturn or there is an epidemic (such as HIV/AIDS) or a natural disaster (like Hurricane Katrina), or new treatments (like drugs for hepatitis C), Medicaid can rapidly respond and federal payments automatically adjust to reflect the added costs of the program.

Capping and reducing federal financing for Medicaid could shift costs to states, beneficiaries, and providers. To respond to reductions in federal funding states could increase state spending to maintain current programs, which would put pressure on other state spending like education. States could also look for program efficiencies, but most Medicaid programs have few options for easy ways to trim spending. Many efficiencies were adopted by states during the last two major recessions when revenues dropped and budgets were constrained. Medicaid already grows at slower rates compared to private health insurance premiums. Most states currently operate programs with low administrative costs and provider reimbursement levels below other payers. Facing federal reductions, states would likely turn to Medicaid program cuts to eligibility, benefits, and reimbursement to providers. These cuts would put populations and providers that disproportionately rely on Medicaid at risk including poor children, the elderly and individuals with disabilities, nursing home and community-based long-term care providers and safety-net hospitals and clinics.