The Affordable Care Act's Impact on Medicaid Eligibility, Enrollment, and Benefits for People with Disabilities

Executive Summary

Medicaid is an important source of health insurance coverage for people with disabilities. This issue brief explains how Medicaid eligibility and benefits for people with disabilities are affected by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) rules as of 2014. Marketplace rules are discussed to the extent that they relate to Medicaid eligibility determinations for people with disabilities.

Medicaid Eligibility Pathways for People with Disabilities

In states that implement the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, more people with disabilities may qualify for Medicaid based solely on their low income status, which enables them to enroll in coverage as quickly as possible, without waiting for a disability determination. As of 2014, the ACA expands Medicaid eligibility up to 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL, $16,104 for an individual in 2014), although implementation of the expansion is effectively a state option. In states that are not implementing the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, people with disabilities can qualify for Medicaid based solely on their low income status if they fit into a coverage group, such as parents and other caretaker relatives, pregnant women, or children, and meet the state’s income limit associated with that group.

People with disabilities can qualify for Medicaid at somewhat higher incomes, up to state-established ceilings, if they also meet disability-related eligibility criteria. Eligibility determinations for disability-related coverage groups continue to be based on existing rules and are not affected by the ACA’s 2014 eligibility and enrollment changes.

People with disabilities who qualify for Medicaid based solely on their low income status can enroll in coverage on that basis and start receiving benefits while their disability-related Medicaid eligibility is being determined. In addition, people with disabilities who do not qualify for Medicaid based solely on their low-income status can enroll in Marketplace coverage with subsidies, if eligible, while their disability-related Medicaid eligibility is being determined.

Medicaid Benefits Packages for People with Disabilities

States must provide alternative benefit plan (ABP) coverage to adults newly eligible for Medicaid. A state’s new adult ABP may not necessarily include all Medicaid state plan benefits, although states can choose an ABP that does so.

In states that do not fully align their new adult ABP with their state plan benefits, a beneficiary’s eligibility pathway determines the contents of her benefits package. Certain populations, including many people with disabilities, must have access to Medicaid state plan benefits, even if they are eligible for Medicaid through the new adult expansion group.In addition, beneficiaries who qualify for Medicaid in both the new adult expansion group (which offers ABP benefits) and a disability-related coverage group (which offers state plan benefits) can choose to enroll in the disability-related coverage group so that they can access the benefits package that best meets their needs.

Identifying Applicants with Disabilities

A key function of the application form is to identify people who may be exempt from ABP enrollment or who may be eligible for Medicaid in a disability-related coverage group because these characteristics can affect the benefits package that a beneficiary receives. Because some people may be reluctant to self-identify as having a disability, it will be important for applicants to understand that answering the disability screening questions can affect the contents of their benefits package. For people applying for coverage through a Marketplace that assesses potential Medicaid eligibility (rather than determining final Medicaid eligibility), there are additional application questions that can affect the type of Medicaid eligibility determination and consequently the benefits package that they receive

Eligibility Renewals

As of 2014, there are new streamlined renewal and reconsideration procedures for poverty-related coverage groups that states also can opt to apply to disability-related coverage groups.

Application Accessibility and Assistance

State Medicaid agencies must ensure that their services are accessible to people with disabilities. For example, state Medicaid agencies must provide auxiliary aids and services at no cost to applicants and beneficiaries; provide information and assistance with the application process in a way that is accessible to people with disabilities; and use accessible applications, forms, and notices. Marketplaces are similarly prohibited from discriminating on the basis of disability and must ensure that their services are accessible to people with disabilities.

Looking Ahead

The ACA’s Medicaid eligibility and enrollment changes may affect people with disabilities. The 2014 rules seek to allow people with disabilities to enroll in coverage as quickly as possible (either in Medicaid based solely on their low income or in a Marketplace QHP with APTC, where eligible), even while their Medicaid eligibility in a disability-related coverage group is being determined. The 2014 rules also seek to ensure that people who qualify in a disability-related Medicaid coverage group or who are medically frail can access the most appropriate benefits package for their needs. As these rules are implemented, it will be important to continue to assess how eligibility and benefits for people with disabilities are affected by the new streamlined eligibility, enrollment and renewal procedures, coordination between state Medicaid agencies and the Marketplaces, application screening questions, and the extent to which states align their new adult ABPs with state plan benefits.

Introduction

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) makes several changes to Medicaid eligibility and enrollment rules that may affect people with disabilities. While the ACA’s adult coverage expansion is effectively a state option, other changes apply to all state Medicaid programs as of 2014, including simplified eligibility determination procedures with a new income counting methodology and increased reliance on electronic data matching; modernizations to the application and renewal processes; and coordination with other insurance affordability programs, including the new Marketplaces that offer qualified health plans (QHPs) and administer advance payment of premium tax credits (APTC) and cost-sharing reductions.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has finalized regulations1 that implement many of the ACA’s changes. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) also has released the single streamlined application that the Secretary was required to develop for use in all insurance affordability programs beginning in 2014.2 This issue brief explains Medicaid eligibility and benefits rules as they pertain to people with disabilities, including relevant changes as of 2014. Provisions of the Marketplace rules are discussed briefly to the extent that they relate to Medicaid eligibility determinations for people with disabilities.3

Background: Medicaid’s Role for People with Disabilities

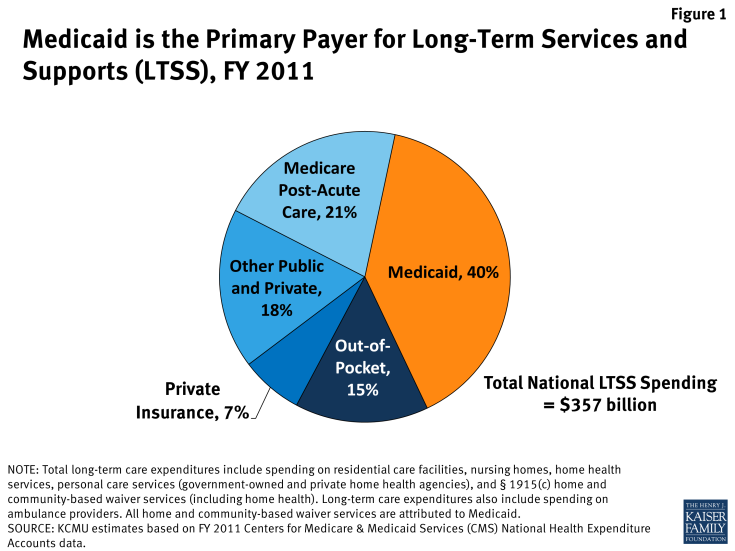

While Medicaid often is regarded as a source of health insurance for people with low incomes, the program also provides important primary or supplemental coverage for people with disabilities. This is true in part because health insurance typically is offered as an employment benefit, making it inaccessible to people with disabilities who are unable to work entirely or to work full-time. In addition, the type and scope of benefits offered by Medicaid include many services essential to people with disabilities that are frequently not covered by private insurance at all or are covered insufficiently to meet the needs of people with disabilities. For example, Medicaid is the primary payer for long-term services and supports, including nursing facility and home and community-based services (HCBS) (Figure 1).

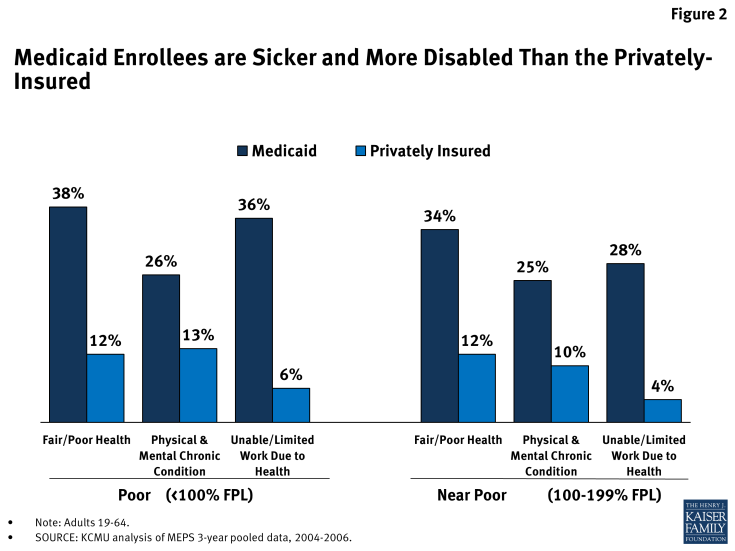

Consequently, the Medicaid population includes a greater prevalence of people with disabilities than the population with private health insurance. As compared to people with private insurance, Medicaid beneficiaries are more likely to be in fair or poor health, to have a chronic condition, and to be unable to work or have a limited ability to work due to their health status (Figure 2).

Over 9.6 million of the nearly 66 million Medicaid beneficiaries in the United States (15%) in 2010 qualify for coverage based upon a disability.4 This figure likely under-represents the total number of Medicaid beneficiaries with disabilities, as some people who qualify for Medicaid based solely upon their low income status (and therefore do not need to establish eligibility based upon a disability) nevertheless may have disabling health conditions.

Medicaid Eligibility Pathways for People with Disabilities

Poverty-Related Coverage Groups

In states that implement the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, more people with disabilities may qualify for Medicaid based solely on their low income status, which enables them to enroll in coverage as quickly as possible, without waiting for a disability determination. The ACA expands Medicaid eligibility up to 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL, $16,104 per year for an individual in 2014) for nearly all non-pregnant adults under age 65, as of 2014.5 Implementation of the ACA’s Medicaid expansion is effectively a state option due to the Supreme Court’s ruling on its constitutionality.6 Twenty-six states (including DC) are implementing the ACA’s Medicaid expansion in 2014, and several other states continue to consider implementation.7

In states that are not implementing the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, people with disabilities can qualify for Medicaid based solely on their low income status if they fit into a coverage group, such as parents and other caretaker relatives, pregnant women, or children, and meet the state’s income limit associated with that group. Financial eligibility limits for these groups remain low and vary across the non-expansion states.8 In all states as of 2014, financial eligibility for parent/caretaker relatives, pregnant women, children, and the new adult expansion group is determined based on the modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) financial methodology, as defined in the Internal Revenue Code. 9 The MAGI methodology involves a single income disregard of 5 FPL percentage points and no asset test. To account for the MAGI methodology’s elimination of other income disregards that states previously used, states converted their pre-2014 Medicaid income limits to MAGI-equivalent limits for their poverty-related coverage groups.

Disability-Related Coverage Groups

People with disabilities can qualify for Medicaid at somewhat higher incomes, up to state-established ceilings, if they also meet disability-related eligibility criteria.10 Some disability-related coverage groups are mandatory for states that choose to participate in the Medicaid program, while others are offered at state option. For example, many states have expanded coverage to people with disabilities who require an institutional level of care at relatively higher incomes than the limits associated with the poverty-related coverage groups. The following general summary is not an exhaustive description of the various Medicaid eligibility pathways for people with disabilities:

- States generally must provide Medicaid to people who receive Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits.11 To be eligible for SSI, beneficiaries must have low incomes, limited assets and a significant disability that impairs their ability to work at a substantial gainful level.12 States also have the option to provide Medicaid to certain other related groups, including people with disabilities whose income exceeds the SSI limits but is still below the federal poverty level (FPL, $11,670 per year for an individual in 2014).13

- Several Medicaid coverage groups require beneficiaries to meet an institutional level of care in addition to financial eligibility requirements. These include people who receive care in institutional settings, such as nursing facilities and intermediate care facilities for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, and people who qualify for home and community-based waiver services. States also can opt to cover children with significant disabilities who would require an institutional level of care if services were not provided at home, based only on the child’s own income, if any, rather than total family income (known as the TEFRA or Katie Beckett option). Establishing Medicaid eligibility in these groups requires an income (and sometimes asset) test as well as an assessment of the extent of a person’s medical needs and functional limitations. The financial eligibility limits associated with these coverage groups are generally significantly higher than those associated with the poverty-related coverage groups. For example, states may opt to cover people who meet an institutional level of care with income up to 300% of the maximum monthly SSI federal benefit rate ($25,956 per year for an individual in 2014).

- The § 1915(i) state plan option allows states to offer Medicaid HCBS to people who meet needs-based criteria that are less stringent than those required to qualify for an institutional level of care. This option permits states to offer HCBS as Medicaid state plan benefits instead of through a waiver to people with incomes up to 150% FPL ($17,505 per year for an individual in 2014) who are already receiving Medicaid. As amended by the ACA, § 1915(i) also creates a new eligibility pathway that permits states to provide full Medicaid benefits, including state plan HCBS, to people who are not otherwise eligible for Medicaid, within certain financial eligibility limits set by the state.14

- States also can opt to provide Medicaid to people who are considered “medically needy” because they have high out-of-pocket unreimbursed medical expenses even though their income otherwise exceeds Medicaid eligibility limits.15 These beneficiaries are permitted to “spend down” to the Medicaid financial eligibility level by subtracting incurred medical expenses from their countable income over an accounting period of one to six months. Once the net result is below the state’s medically needy income level, the person is eligible for Medicaid for the remainder of the accounting period. The ability to establish Medicaid eligibility via a spend down is especially important for people in nursing facilities and people with disabilities living in the community who incur high health care costs.

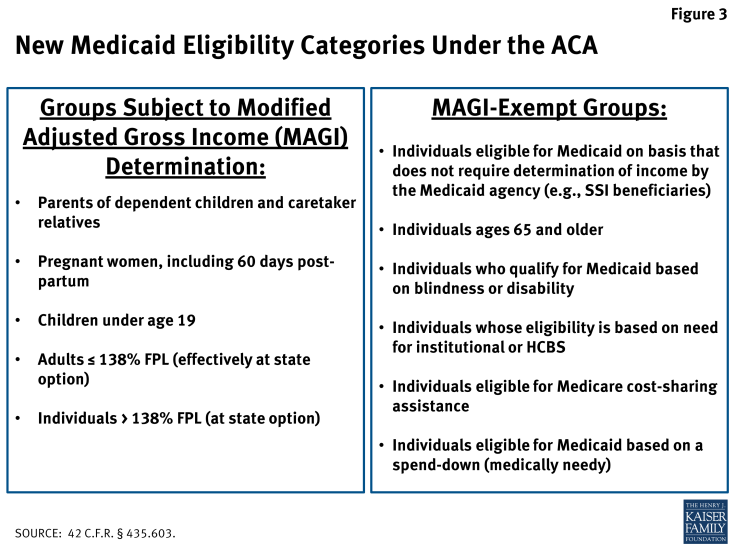

Medicaid eligibility determinations for disability-related coverage groups continue to be based on pre-existing rules and are not affected by the ACA’s 2014 eligibility and enrollment changes. Specifically, people who are eligible for Medicaid on a basis that does not require the determination of income by the state Medicaid agency (such as SSI beneficiaries); people who qualify for Medicaid on the basis of blindness or disability; and people whose eligibility is based on their need for institutional or home and community-based long-term care services are exempt from the use of the MAGI financial methodology.16 The groups subject to and exempt from MAGI-based Medicaid financial eligibility determinations are summarized in Figure 3.

Access to Coverage While Awaiting a Medicaid Disability Determination

People with disabilities who qualify for Medicaid based solely on their low income status can enroll in coverage on that basis and start receiving benefits while they are waiting for the completion of a disability-based Medicaid eligibility determination.17 Applicants always will have their Medicaid eligibility assessed solely on the basis of income as the first step in the eligibility determination process. This can be helpful to beneficiaries because it likely takes less time to determine whether someone’s countable income is below 138% FPL (or the MAGI-equivalent income limit in states that do not implement the ACA’s Medicaid expansion) than to evaluate the medical and functional criteria necessary to determine whether someone is eligible for Medicaid based upon a disability. States still have 90 days to make disability-related Medicaid eligibility determinations (and 45 days for non-disability based determinations), although interim final regulations also require state Medicaid agencies to establish timeliness and performance standards to ensure that all eligibility determinations are made “promptly and without undue delay,”18 as the ACA envisions an eligibility determination system that is highly reliant on electronic data matching and makes decisions in as close to “real time” as possible.

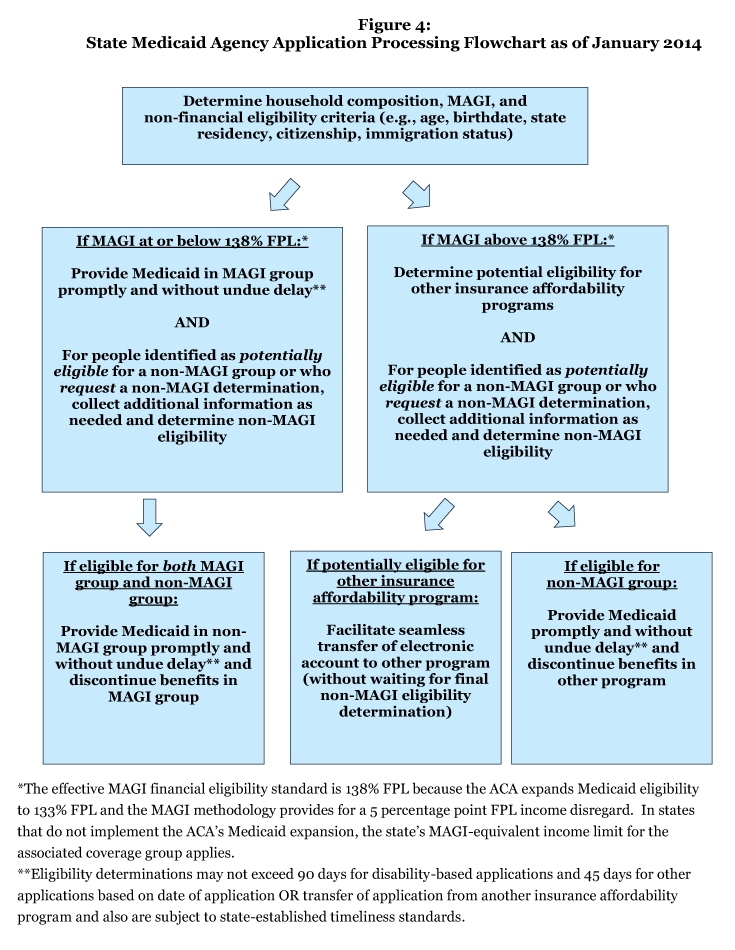

In addition, people with disabilities who do not qualify for Medicaid based solely on their low-income status can enroll in Marketplace QHP coverage with APTC, if eligible, while their disability-related Medicaid eligibility is being determined. If a person is ineligible for Medicaid in a poverty-related group but appears eligible (based on information provided in an application or renewal form) or requests a Medicaid eligibility determination in a disability-related group, the state Medicaid agency must simultaneously (1) assess the person’s potential eligibility for other insurance affordability programs, such as Marketplace subsidies, and (2) determine the person’s eligibility for Medicaid in disability-related coverage groups.19 If the state Medicaid agency finds that such a person is potentially eligible for Marketplace subsidies, the state Medicaid agency must electronically transfer the person’s application to the Marketplace without waiting for the disability-related Medicaid eligibility determination to be completed.20 The person can then enroll in Marketplace coverage, if eligible, while her disability-related Medicaid application is pending.21 If she is ultimately determined eligible for Medicaid in a disability-related coverage group, she will then enroll in Medicaid and disenroll from Marketplace coverage. In these cases, such individuals are not liable to repay any APTC for Marketplace coverage received in the interim.22 Figure 4 illustrates the Medicaid eligibility determination process that state Medicaid agencies must follow as of 2014.

Medicaid Benefits Packages for People with Disabilities

Alternative Benefit Plans for Newly Eligible Adults

Under the ACA, states must provide alternative benefit plan (ABP) coverage to people who are newly eligible for Medicaid in the adult expansion group. Since 2006, states have had the option to provide an ABP (formerly called benchmark benefits) to certain Medicaid populations, instead of the state plan benefits package, although few states had done so. An ABP is a set of covered services based on one of three commercial insurance plans or determined appropriate by the HHS Secretary. States also have the option to implement different ABPs targeted to different subpopulations, such as beneficiaries in different geographic areas or beneficiaries with particular medical needs.23

A state’s ABP for newly eligible adults must include the ten categories of essential health benefits (EHB) required by the ACA,24 provide parity in coverage between physical and mental health services,25 and offer certain preventive services; it may not necessarily include all of the benefits offered in the Medicaid state plan.26 ABP coverage of the essential health benefits cannot be based on a design that discriminates on the basis of disability.27 However, the regulations do not define how such disability-based discrimination will be identified and enforced.

ABP Exemptions and Access to State Plan Benefits

Certain populations, including many people with disabilities, cannot be required to enroll in an ABP and instead must have access to Medicaid state plan benefits, even if they are eligible for Medicaid through the new adult expansion group.28 ABP-exempt groups include many people with disabilities, such as:

- people who are blind or have disabilities (regardless of whether they qualify for SSI);

- children with disabilities eligible under the Katie Beckett state plan option;

- people dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid;

- people who are terminally ill and receiving hospice care;

- people who live in institutions and receive only a personal needs allowance;

- people who are medically frail and people with special medical needs (as of 2014, the definition of “medically frail” beneficiaries is expanded to include people with chronic substance use disorders);29

- people with developmental disabilities and seniors who qualify for nursing facility or equivalent institutional services or home and community-based waiver services;

- women receiving treatment for breast or cervical cancer;

- people who qualify for Medicaid based upon TB infection; and

- people who qualify for Medicaid as medically needy based upon a spend down.

People who are exempt from mandatory ABP enrollment receive Medicaid state plan benefits, including certain mandatory federal benefits and any optional benefits that the state elects to cover.30 In addition to Medicaid state plan benefits, people with disabilities who qualify for home and community-based waiver services receive additional benefits that can be targeted to their health needs, are not available to other Medicaid beneficiaries, and can include services that are not strictly medical in nature. Medicaid-funded HCBS are important because they provide necessary supports that enable people with disabilities to live independently in the community as an alternative to institutional care.31

Alignment of New Adult ABPs with State Plan Benefits

States can choose to offer an ABP to their new adult expansion group that contains the same benefits as their state plan.32 This can be accomplished by electing “Secretary-approved coverage” as the state’s ABP benchmark. As of 2014, the definition of “Secretary-approved coverage” is expanded so that those ABPs can include any Medicaid state plan benefit, including HCBS available under the § 1915(i) state plan option, § 1915(j) self-directed personal assistance services, and § 1915(k) Community First Choice attendant services and supports.33 To fully align the benefits between an ABP and the state plan, states must determine which state plan benefits (such as HCBS) must be added to the ABP and which ABP benefits (such as behavioral health and preventive services) must be added to the state plan.

In states that do not fully align their new adult ABP with their state plan benefits, a beneficiary’s eligibility pathway determines the contents of her benefits package. This is significant because Medicaid state plan benefits typically include at least some HCBS that are important to people with disabilities, such as home health services and at state option, personal care services. The state’s new adult ABP may not necessarily include the same types and amounts of HCBS as the state plan. On the other hand, Medicaid state plan benefits may not cover behavioral health and/or preventive services to the same extent as the new adult ABP, due to the mental health parity and EHB requirements that apply to ABPs.

Beneficiary Choice of Eligibility Pathway and Benefits Package When ABP and State Plan Do Not Align

Beneficiaries who qualify for Medicaid in both the new adult expansion group (which receives ABP benefits) and a disability-related coverage group (which receives state plan benefits) can choose to enroll in the disability-related coverage group so that they can access the benefits package that best meets their needs.34 This rule is designed to ensure that people with disabilities can obtain Medicaid state plan benefits, such as HCBS, that may not be included in the new adult ABP in states that do not align benefits packages. This rule also preserves a pathway for people with disabilities to access Medicaid home and community-based waiver services, which may not be available or available to the same extent in either the state plan or the new adult ABP. Once a beneficiary is determined eligible in a disability-related coverage group, she will be enrolled in that group and will no longer be eligible for Medicaid in a poverty-related group, unless and until her circumstances change.35 However, beneficiaries who are eligible for Medicaid based solely on their low income cannot be required to provide any additional information needed to determine their Medicaid eligibility in a disability-related coverage group.36 This preserves a beneficiary’s right to remain in the new adult coverage group and receive the ABP if that benefits package is preferable, instead of transferring to a disability-related coverage group and receiving state plan benefits.

Identification of Applicants with Disabilities

A key function of the application form is to identify people who may be exempt from ABP enrollment as medically frail or who may be eligible for Medicaid in a disability-related coverage group because these characteristics can affect the benefits package that a beneficiary receives. Applicants may be so identified based on information collected in the single streamlined application developed by the HHS Secretary or a renewal form or otherwise available to the state. To collect any additional information needed to determine disability-related Medicaid eligibility, the state Medicaid agency can either use the single streamlined application along with supplemental forms or an application specifically designed for disability-related eligibility determinations so long as the burden on applicants is minimized.37

Because some people may be reluctant to self-identify as having a disability, it will be important for applicants to understand that answering the disability screening questions can affect the contents of their benefits package. As described below, states must provide information to applicants and beneficiaries about the different Medicaid coverage groups and associated benefits packages so that people can make an informed decision about whether to seek coverage in a disability-related group with a benefits package that may better meet their needs. The online version of the single streamlined application contains two questions designed to identify people with disabilities: applicants are asked whether they have a physical disability or mental health condition that limits their ability to work, attend school, or take care of their daily needs; and whether they need help with activities of daily living (such as bathing, dressing, and using the bathroom) or live in a medical facility or nursing home.38 Depending upon the effectiveness of these questions, additional screening questions about the extent of an applicant’s functional limitations might help to identify people who may qualify for Medicaid based on a disability or meet an ABP exemption even though they do not perceive themselves as having a disability.

For people applying for coverage through a Marketplace that assesses potential Medicaid eligibility (rather than determining final Medicaid eligibility), there are additional application questions that can affect the type of Medicaid eligibility determination that they receive and consequently their benefits package. First, when a Marketplace assesses someone as potentially ineligible for Medicaid, applicants are then asked whether they want to have their application sent to the state Medicaid agency for an actual Medicaid eligibility determination or whether they want to withdraw their Medicaid application.39 It is important for applicants to understand that a decision to withdraw their Medicaid application deprives them of the right to appeal the Medicaid eligibility denial40 and the key differences (e.g., benefits, cost sharing) between Medicaid and Marketplace coverage so that they can make an informed choice about whether to pursue a final Medicaid eligibility determination (including in disability-related coverage groups). Second, applicants are asked whether they want the state Medicaid agency to determine their Medicaid eligibility based on disability, blindness or recurring medical bills and needs.41 It is important for applicants to understand that they have the right to request this determination and that doing so can affect their ability to access Medicaid state plan benefits, such as HCBS, that may not be included in the state’s new adult ABP.

Eligibility Renewals

As of 2014, there are new streamlined renewal and reconsideration procedures for poverty-related (MAGI) coverage groups that states also can opt to apply to disability-related (non-MAGI) coverage groups.42 Specifically, state Medicaid agencies are prohibited from requiring in-person interviews for MAGI-eligible beneficiaries; must send a pre-populated renewal form to MAGI-eligible beneficiaries; and must reconsider the eligibility of MAGI-related beneficiaries without requiring the submission of a new application if a person whose benefits have been terminated for lack of response to a renewal form subsequently returns the renewal form within 90 days of the date of termination.43 For both MAGI and non-MAGI groups, the state Medicaid agency must renew eligibility for benefits if possible based on the information available to the agency without requiring additional information from the beneficiary.44 Medicaid eligibility must be renewed once every 12 months for MAGI-related groups and at least every 12 months for non-MAGI groups.45

Application Accessibility and Assistance

State Medicaid agencies have the option to certify application counselors, including staff and volunteers from state-designated organizations, to help applicants and beneficiaries with the application and eligibility renewal process.46 These application counselors are available to all beneficiaries, not just those with disabilities. However, CMS has proposed that application counselor programs must ensure equal access to people with disabilities, such as by providing auxiliary aids and services (described below).47 Applicants and beneficiaries also may designate an individual or organization to act on their behalf as an authorized representative to apply for and renew eligibility and handle other communications with the state Medicaid agency. 48

State Medicaid agencies must ensure that their services are accessible to people with disabilities. Specifically, state Medicaid agencies must comply with two major federal civil rights laws that protect people with disabilities, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act. The ADA generally prohibits disability-based discrimination by state and local governmental entities and places of public accommodation, and Section 504 does the same for recipients of federal funds.

While the applicability of the ADA and Section 504 to state Medicaid agencies is not new, CMS has explicitly confirmed that state Medicaid agencies must provide auxiliary aids and services at no cost to applicants and beneficiaries as part of their ADA and Section 504 obligations.49 CMS also proposed but has not yet finalized a provision requiring applicants and beneficiaries to be informed about the availability of and how to access auxiliary aids and services.50 Auxiliary aids and services can include, as appropriate, qualified interpreters, a variety of assistive technology devices, and the provision of materials in alternative formats to ensure effective communication and accessibility for people with hearing, visual, and other disabilities.51

The ADA and Section 504 also require state Medicaid agencies to:

- provide information about eligibility requirements, available Medicaid services, and the rights and responsibilities of applicants and beneficiaries in a way that is accessible to people with disabilities.52 This information must be provided to all applicants and anyone who requests it, not just people with disabilities. Information must be available in paper and electronic forms, including online, and orally as appropriate, and must be provided in plain language.

- provide assistance to people seeking help with the application or renewal process in a manner that is accessible to people with disabilities.53 This assistance must be provided to anyone, not just people with disabilities, and must be available in person, by phone, and online. State Medicaid agencies also must allow applicants and beneficiaries to have a person of their choice assist them with the application and renewal process.

- use applications, supplemental forms, renewal forms and notices that are accessible to people with disabilities.54 CMS intends to issue future guidance with specific accessibility standards after consulting with states and other stakeholders.

Marketplaces similarly are prohibited from discriminating on the basis of disability and must ensure that their services are accessible to people with disabilities.55 Like state Medicaid agencies, Marketplaces must provide auxiliary aids and services to people with disabilities and inform applicants and enrollees about the availability of such services and how to access them in accordance with the ADA and Section 504.56 A Marketplace’s obligation to ensure that its services are accessible to people with disabilities extends to its call center; website; consumer assistance functions, including navigators; outreach and education activities; and all applications, forms, and notices.57 Marketplaces also must consult regularly with various groups such as advocates for enrolling hard to reach populations, including people with mental health or substance use disorders.58 HHS plans to issue specific Marketplace accessibility standards in future guidance.

Looking Ahead

The ACA’s Medicaid eligibility and enrollment changes can affect applicants and beneficiaries with disabilities. The 2014 rules seek to allow people with disabilities to enroll in coverage as quickly as possible (either in Medicaid based solely on their low income or in a Marketplace QHP with APTC, where eligible), even while their Medicaid eligibility in a disability-related coverage group is being determined. The 2014 rules also seek to ensure that people who qualify in a disability-related Medicaid coverage group or who are medically frail can access the most appropriate benefits package for their needs. As the ACA’s 2014 eligibility and enrollment rules are implemented, it will be important to continue to assess how eligibility determinations and benefits for people with disabilities are affected by the new streamlined eligibility, enrollment and renewal procedures, coordination between state Medicaid agencies and the Marketplaces, the application screening questions, and the extent to which states align their new adult ABPs with state plan benefits.